angaroo mother care (KMC) is an evidence-based

cost effective approach, and can avert up to 450,000 preterm deaths each

year if near-universal coverage is achieved [1,2]. Invest-ment in KMC

has benefits beyond survival including healthy growth and long term

development [3,4].

However, despite its known benefits, the adoption and

implementation of KMC has been low. Even at the places where KMC is

being practiced in the facility, the number of hours of KMC remain low.

Average duration of KMC varies from 3-5 h/day in previous Indian studies

[5,6]. Various potential barriers to KMC include issues with facility

resources and environment, negative impressions about staff attitude,

and lack of awareness about KMC benefits [7].

A recent study in our unit reported median (IQR) KMC

duration in eligible preterm infants of 3.14 (2.1-4.3) h/day. To address

this problem we used QI approach to target the bottle neck areas in a

step-wise manner. We formulated an aim statement to increase the

duration of KMC per day from a current baseline of 3 hours to 6 hours in

admitted eligible preterm mother- infant dyads.

Methods

Our hospital has a 10-bedded level III and a

20-bedded level II NICU in addition to 8 Kangaroo mother care and

rooming-in beds. Each eligible mother-infant dyad was a single

participant in the present study. All eligible preterm neonate admitted

in NICU were included. Sick neonates [defined as those requiring

invasive or non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NIMV) or shock (defined

as the presence of tachycardia (heart rate more than 180 beats/minute,

extremities cold to touch, and capillary fill time more than 3 seconds,

with or without pallor, lethargy or unconsciousness) or apnea (>4 apneas

in the last 24 h)], neonates receiving phototherapy, and for whom no

eligible relatives were available and/or the mother was sick or

discharged from the hospital were excluded.

A team comprising one faculty in-charge, one resident

physician, one nurse educator and two senior staff nurses was formed to

evaluate the barriers for improved KMC duration and to plan the

subsequent steps for promoting the same.

In baseline phase, data was collected in a

predesigned proforma for 10 days for ten eligible preterm infant-mother

dyads. We tried to evaluate various barriers faced by mother as well as

staff members for providing KMC of pre-specified duration by using

another proforma. The barriers were identified using fish bone analysis

(Web Fig. 1). The predominant barriers were

lack of adequate support to mother, absence of formal counselling on KMC

by the healthcare team, and other maternal factors including lack of

privacy, stress and fatigue. On one-to-one discussion with the mothers,

the authors found that they were spending nearly 5 hours of the day for

expression of breast milk and almost a similar duration for feeding the

baby (total 10 hours), and no KMC was being practiced during the night

hours.

A comprehensive KMC improvement package was planned.

This consisted of two main elements: one was education and sensitization

of health care providers and family members and secondly, a simultaneous

reinforcement of ongoing practice. We took some corrective steps which

included felicitation for both relatives as well as staff-nurses. These

changes were tested as a part of Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle. We

conducted three PDSA cycles (Web Table I).

A combined meeting of the nurse-educator, team leader

nurses, other staff nurses, and resident doctors was conducted every

week in the implementation phase for apprising every one of the current

situation. For sustenance of the improvement initiative, the combined

meeting was conducted on a monthly basis and the results were collected

on an ongoing basis and reviewed fortnightly, and continuous feedback to

given to all staff.

The primary outcome measure was the duration of KMC.

This was evaluated by staff nurse on duty by recording the exact hours

of KMC in each 8-hour shift and then adding total duration of 3

shifts/day) in eligible preterm infant-mother dyads. The duration was

then plotted on a run-chart. The outcome was evaluated daily in

implementation phase, and one day every fortnight in post-implementation

phase.

Data analysis: The data was coded and analyzed

statistically using STATA version 11.1 (Stata Corp, College station,

Texas, US). A P value of <0.05 was taken as significant.

Results

The baseline demographic characteristics of mother as

well as preterm infant were similar in both the phases (Baseline phase

and implementation phase) (Table I). The biggest barrier

to successful implementation of KMC was absence of formal KMC

counselling for the mothers and family members. We hypothesized that

educating them regarding benefit of KMC would be useful.

TABLE I Baseline Characteristics of Participants

Parameter

|

Baseline phase

(n=10) |

Implementation phase

(n=20) |

|

Maternal age, y |

29.4 (5.1) |

30.3 (4.1) |

|

Gestational age, wks |

30.9 (6.2) |

31.1 (2.3) |

|

Birthweight, g |

1359 (305) |

1199 (356) |

|

Primipara mother* |

5 (50) |

19 (95) |

|

Mother’s education#

|

7 (70) |

14 (70) |

|

Males |

6 (60) |

8 (40) |

|

GA<32 wk |

4 (40) |

7 (35) |

|

Small for GA |

5 (50) |

7 (35) |

|

Need for resucitation |

2 (20) |

6 (30) |

|

Data expressed as number (%) or mean (SD); *P<0.001;

#Graduate or above. |

As a part of PDSA Cycle 1 (first two weeks), four

nursing staff working in NICU in different shifts were identified and

were involved in comprehensive counselling and on KMC for the mothers

and their family members. This included creation of supportive

environment in NICU for KMC, and showing them videos and pictorial

charts on KMC in small groups. One-to-one counselling of mother and

family members on KMC and its benefits was done by the assigned bedside

nurse. Encouragement and acknowledgment of mothers and family members

for increasing the duration of KMC was done by the nurses. The mean

duration of KMC increased from 3.25 hours to 4.5 hours by the end of

first PDSA cycle (Web Fig. 2). The resident

doctors included emphasis of KMC duration as a part of daily treatment

order.

In PDSA Cycle 2 (3/font>rd

and 4th week) the overall

target of 6 hours was split as ensuring at least 2 hours in each shift

by the respective nursing staff. The staff nurses were felicitated for

ensuring maximum KMC hours in their shifts on weekly basis in periodic

meetings. We also ensured availability of more breast-pumps (total

number of electronic breast pumps was increased from 2 to 4) which

resulted in decrease in waiting time for mother’s expression of milk

with breast pumps. The average duration of KMC increased to more than 6

hours (at the end of 4th week). During the 5th week of the project the

mean duration of KMC declined slightly. This was postulated due to lack

of active participation of infants in KMC who were in respiratory

support. So in PDSA Cycle 3, the assigned nurses were made available

round the clock with babies and mothers/family members at the time of

KMC, especially who were on some kind of respiratory support like oxygen

therapy and non-invasive ventilation to build up their confidence and

alleviate anxiety and fear related to baby’s desaturation at the time of

KMC. Nurses provided constant positive re-enforcement and encouragement

to the mothers and the family members for doing KMC. At the end of 7

weeks, average number of hours of KMC increased from 4.1 to 7.2 hours.

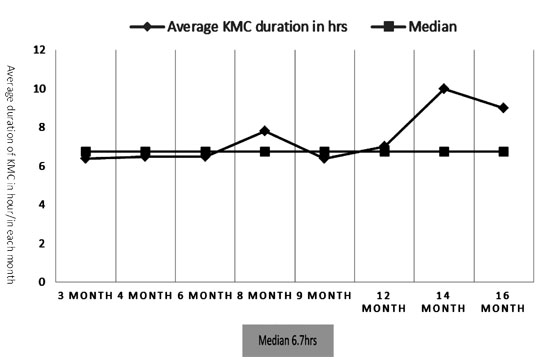

We were able to sustain improved average KMC duration

in the unit in post-implementation phase, even after 1 year of

completion of QI project. Fathers and other close family members are

allowed to give KMC in the unit even at night time, so that mothers can

get rest. Even after one year of implementation of study, the duration

of KMC among all eligible babies remains around 9 h/day (Fig.

1).

|

|

Fig. 1 Sustenance of KMC in

post-implementation phase.

|

One of the balancing outcomes which the QI team found

during the study process was an increase in the breakage of temperature

probes of radiant warmer due to excessive dragging of probes while

babies were transferred from radiant warmer to caregiver for initiation

of KMC. However, this was subsequently sorted out by careful detachment

of probes from radiant warmer side by staff nurses each time KMC was

started for a baby.

Discussion

Maternal lack of time and supportive environment and

fatigue were the main barriers for practice of optimum KMC [7]. Hence,

allowing other family members for KMC addressed these issues. Active

involvement of family members not only scales- up facility based KMC,

but it is also known to sustain home-based KMC after discharge [8].

Although increasing staff support and implementing

temporary project staff is known to scale up KMC practices, the effect

seems transient and fades with withdrawal of support [8,9]. A unique

effort in our study was the utilization of existing resources and

infrastructure for strengthening KMC.

Audit-and-feedback is considered as one of the

backbones of quality improvement initiative for changing healthworker

behavior as well as an ongoing policy which formed an important

milestone in our study. We conducted weekly audit in our study to

evaluate the potential reasons for decreased KMC duration. In addition,

the concept of weekly declaration of champions encouraged the healthcare

providers. Similar role of healthcare champions has been described in

recent studies from Western India [5].

Our study was a single-center quality improvement

initiative. The limitation of the study was that the morbidity data was

not evaluated. The data on day of KMC initiation, details on KMC

continuation after discharge for each baby was not prospectively

collected. Mothers were not comfortable doing KMC while they were

walking or eating. Similarly the idea of pumping of both breasts

simultaneously to save time were not adopted by our mothers. We hence

resorted to active involvement of other family members for facilitating

KMC. Although we could reach our target of 6 hours as planned for this

initiative, this is still low as per the WHO standard. However, we feel

that with continuation of education in post-implementation phase further

improvement is expected.

We demonstrated feasibility and sustainability of a

simple quality improvement approach for increasing KMC duration in

eligible preterm neonates. This was achieved within existing resources

without addition of extra manpower by involving family members.