|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2016;53: S57-S60 |

|

Role of Global Alliance

for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI) in Accelerating Inactivated

Polio Vaccine Introduction

|

|

Naveen Thacker, #Deep

Thacker and #Ashish

Pathak

From Deep Children Hospital and Research Centre,

Gandhidham, and #Department of Pediatrics, RD Gardi Medical

College, Ujjain, Madhya Pradesh, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Ashish Pathak, Professor,

Department of Pediatrics, RD Gardi Medical College, Ujjain, Madhya

Pradesh, India.

Email:

[email protected]

|

Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI, the Vaccine

Alliance) is an international organization built through public-private

partnership. GAVI has supported more than 200 vaccine introductions in

the last 5 years by financing major proportion of costs of vaccine to 73

low-income countries using a co-financing model. GAVI has worked in

close co-ordination with Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI)

since 2013, to strengthen health systems in countries so as to

accelerate introduction of inactivated polio vaccine (IPV). GAVI is

involved in many IPV related issues like demand generation, supply,

market shaping, communications, country readiness etc. Most of the 73

GAVI eligible countries are also high priority countries for GPEI. GAVI

support has helped India to accelerate introduction of IPV in all its

states. However, GAVI faces challenges in IPV supply-related issues in

the near future. It also needs to play a key role in global polio legacy

planning and implementation.

Keywords: GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance, Global Polio

Eradication Initiative, IPV.

|

|

G

lobal Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization

(GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance) is an international organization, which was

created as a public-private partnership. GAVI brings together United

Nations Childrenís Fund (UNICEF), the World Bank, the vaccine

manufactures from resource rich and resource poor countries, donors from

the resource rich countries, and representatives from governments of the

low-income countries across the world and Civil Society Organizations

(CSOs)[1]. Since its inception in 2000, GAVIís support has contributed

to the immunization of an additional 500 million children in low-income

countries and has averted 7 million deaths due to vaccine preventable

diseases. GAVI has supported more than 200 vaccine introductions and

campaigns in low-income countries during the 2011-2015 period [1].

The mission of GAVI is "Saving childrenís lives and

protecting peopleís health by increasing equitable use of vaccines in

lower-income countries" [1]. GAVI is dependent on the effectiveness of

the countries health-system to deliver life-saving vaccines, thus GAVI

supports countries to strengthen country health system by proving health

system strengthening (HSS) grants. Both GAVI and GPEI have committed to

strengthen immunization programs to introduce IPV and withdraw oral

polio vaccine (OPV) as per the Polio Eradication Endgame Strategic Plan

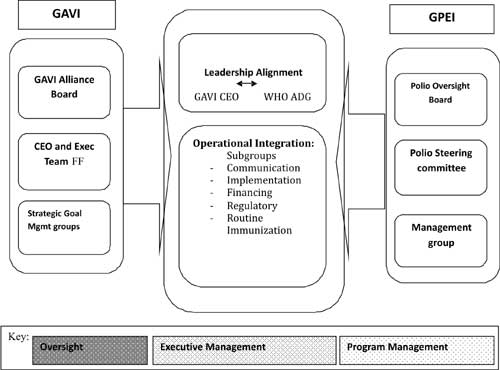

2013-2018 [2]. The GAVI board and GPEI recognized the synergies to work

together and developed common goals, objectives, oversight mechanisms,

accountability mechanism and common program management as shown in

Fig. 1.

|

|

Fig.1 *GAVIís framework for

co-ordination with Global Polio Eradication Initiative.

*Adopted from Document 11a-GAVIís complimentary role on

Polio-approach available from

http://www.polioeradication.org/Portals/0/Document/Resources/StrategyWork/PEESP_CH6_EN_US.pdf.

|

Basis of GAVI support to Countries. GAVI

invites applications for support from governments of those countries

whose gross national income per capita is below GAVIís eligibility

threshold, this threshold was US dollar 1580 in the year 2015 [3]. Based

on the eligibility threshold, 73 countries are eligible for GAVI

support. GAVI purchases vaccines through UNICEF, and provides them to

governments whose applications are approved [3,4].

GAVI Alliance Complements Polio Eradication Efforts

The overall objective of GAVIís engagement with polio

eradication is a complimentary approach to the GPEI, which is "to

improve immunization services in accordance with GAVIís mission and

goals while supporting polio eradication by harnessing the complementary

strengths of GAVI and GPEI in support of countries" [5].

The most important issues related to IPV introduction

that GAVI is helping to resolve are: (a) demand, supply and

market-shaping implications; (b) communications and country

dialogue on IPV introduction; (c) IPV implementation including

prioritisation of countries, countryís readiness, and preparation for

introduction, and (d) initial projections of financial resource

requirements [5].

GAVIís support to countries ensures that the

countries with stretched and burdened healthcare and immunization

systems receive technical assistance. To achieve this GAVI works with

country partners WHO, UNICEF and CSOís to develop training material,

traine the healthcare workers to overcome communication challenges,

develop immunization-tracking system, and strengthen cold chain and cold

chain management capacity. GAVI has also encouraged countries to look at

IPV introduction in a larger global context of polio endgame strategy.

GAVI has ensured that material and tools for the best practice for

administration of multiple vaccinations are also provided to the

countries with the help of UNICEF country offices.

For the introduction of IPV, GPEI has prioritized

countries in four tiers, based on three criteria; endemicity of wild

poliovirus, history of cVDPV emergence, and routine immunization

coverage (Table I) [6]. Tier 1 contain the highest

priority countries for IPV introduction and include the endemic

countries. All tier 1 countries except China are GAVI countries. Most

tier 2 countries are also GAVI eligible countries. The concentration of

GAVI countries in tiers 1 and 2 affirms the importance of GAVI policies,

which incentivize rapid introduction [6].

TABLE I Priority of Countries for IPV Introduction

|

Tier |

Description of criteria |

Number of countries

|

% of OPV birth control

|

|

Tier1 |

WPV endemic countries OR countries that have reported a cVDPV2

since 2011 |

14 |

61% (38% attributable to India and China.)

|

|

Tier 2 |

Countries who have reported a cVDPV1/cVDPV3 since 2001 OR

large/medium2 sized countries with DTP3 coverage <80% in

2009,2010, 2011 as per WUNIC

|

19 |

11%

|

|

Tier 3 |

Large/ medium2 countries adjacent to Tier 1 countries that

reported |

14 |

11%

|

|

WPV since 2003 OR countries that have experience a WPV

|

|

|

|

importation since 2011

|

|

|

|

Tier 4

|

All other OPV only using countries

|

77 |

17% |

IPV Introduction in India

India has always been special for GAVI because with a

birth-cohort of almost 27 million, India is the most populous

GAVI-eligible country [7]. Also, India still accounts for one-fifth of

child deaths worldwide and more than a quarter of all under-immunised

children in GAVI-eligible countries [7]. India remains eligible for GAVI

support based on its GNI level [7]. Yet, given the large birth cohort of

the country, GAVI has limited its support to catalytic funding to India.

Until 2011, there was a limit placed on GAVI support to India, which was

removed with the condition that the Board continues to review any new

support case-by-case [7].

The National Technical Advisory Group on Immunization

(NTAGI), the apex body for decision-making on immunization related

issues in India, recommended a comprehensive IPV introduction plan to

the Government of India (GoI) [8]. India applied for funding to GAVI in

September 2014, for the period of September 2015 to 2018 at an estimated

cost of US dollar 160 million. In November 2015, India launched IPV in

six states and has recently expanded it to all states and Union

Territories [9].

Health System Strengthening (HSS) Support to India

GAVI has disbursed US dollar 30.6 million for the IPV

introduction and US dollar 107 million in the year 2014-15 [10]. The

grant has been focused by GoI for use in 12 states and 127

underperforming districts and is synergistic to Mission Indradhanush

[10]. Specifically, the grant has been used to strengthen the cold chain

management. To enhance human resource capacity, National cold chain

vaccine management resource center has been established in New Delhi

[10]. National cold chain training center has been strengthened in Pune

[10]. In 20 districts across UP, MP and Rajasthan, electronic vaccine

intelligence network (eVIN) has been implemented to enable real time

information on cold chain temperatures, vaccine stocks and flows [10].

To increase demand for routine vaccination, National behavioral change

and communication (BCC) strategy has been developed and immunization

messages have been developed and broadcast through mass media [10]. The

National monitoring and evaluation plan for immunization has been

drafted and monitoring and evaluation of routine immunization is

currently functional in 24 of the 36 states across India [10]. Two

rounds of survey for National Immunization Coverage Evaluation have been

done in 2015. This evaluation will further identify low performing

districts for routine immunization coverage [10]. Guidelines for tagging

high-risk low coverage areas have been developed along with WHO India

National polio surveillance program (NPSP) [10].

Financing the Polio End Game Globally

Globally, US dollar 11 billion have been invested in

the GPIE since its inception in 1988 [2]. A total of US dollar 5.5

billion are being invested for the polio eradication and endgame

strategic plan [2]. An investment of US dollar 5.5 billion today in

polio eradication is expected to yield up-to US dollar 40 to 50 billion

in additional net benefit in subsequent 20 years for the worldís poorest

countries [11]. The bases of calculation for these gains are from

avoided treatment costs and productivity gains [11]. Today, more than 10

million people are walking who would otherwise have been paralyzed by

the poliovirus [12].

Challenges for the Future

There have been challenges in the availability of IPV

because of which 28 countries had to delay their planned dates to

introduce IPV. In eight countries, the IPV introduction was delayed to

after the trivalent to bivalent OPV switch, after April 2016. It is

expected that supply constraints will remain till end of 2018 because of

two main reasons: firstly, delays in the manufacture production scale-up

due to technical reasons; and secondly, increased use of IPV in

campaigns [9].

Globally there is a need to plan for the "polio

legacy". The term "polio legacy" refers to the investments made

in polio eradication that can be shifted to meet other crucial health

goals [13]. Strengthening health systems to increase coverage levels in

routine immunization to more than 85% for DPT3 in all districts across

countries globally, including India, is one of the most important

challenges. Strengthening systems to introduce IPV will also catalyze

the delivery of other lifesaving vaccines like pneumococcal, rotavirus

and human papilloma virus which are in line to be introduced in National

immunization schedule by GAVI support [7]. One practical programmatic

problem, which India avoided, was shortage of cold chain space as it

introduced IPV in states where pentavalent vaccines were already

introduced. From scientific point of view, we need more research into

economic aspects of the vaccination program including impact of new

vaccine introduction, cost of delivering a vaccine in rural, urban and

tribal areas, methods to evaluate vaccine effectiveness and decision

tools for policy makers. From a practicing pediatrician point of view we

need to ensure that a child that is eligible to receive polio should not

leave a clinic without receiving a polio vaccine.

Funding: None; Competing interest: NT is

GAVI Board member representing civil society organizations and AP is

special advisor to NT.

References

1. GAVI 2016. Every Child Counts: The Vaccine

Alliance Progress Report 2014. Available from

http://www.GAVI.org/progress-report/. Accessed May 13, 2016.

2. GPEI 2013. Polio Eradication and Endgame Strategic

Plan 2013Ė2018. Available from

www.polioeradication.org/Portals/0/Document/Resources/StrategyWork/EndGameStratPlan_20130414_ENG.pdf.

Accessed May 13, 2016.

3. Kallenberg J, Mok W, Newman R, Nguyen A, Ryckman

T, Saxenian H, et al. GAVIís Transition Policy: Moving From

Development Assistance To Domestic Financing Of Immunization Programs.

Health Affairs. 2016;35:250-8.

4. Shen AK, Weiss JM, Andrus JK, Pecenka C, Atherly

D, Taylor K, et al. Country ownership and GAVI transition:

Comprehensive approaches to supporting new vaccine introduction. Health

Affairs. 2016;35:272-6.

5. GAVI Alliance Polio Eradication Efforts, Available

from

http://www.GAVI.org/Library/News/GAVI-features/2014/GAVI-Alliance-complements-global-polio-eradication-effort/.

Accessed May 13, 2016.

6. WHO-Risk tiers for IPV introduction, Available

from http://www.who.int/immunization_standards/vaccine_

quality/4a_risk_tiers_for_ipv_introduction.pdf. Accessed May 13,

2016.

7. GAVI 2015. Alliance Partnership Strategy with

India, 2016-2021 Report to the Board 3rd December 2015. Available from

http://www.GAVI.org/Library/News/Press-releases/2016/Historic-partnership-between-GAVI-and-India-to-save-millions-of-lives/.Accessed

May 13, 2016.

8. WHO 2016 India Expert Advisory

Group (IEAG) February 26, 2016 meeting. Available from

http://www.who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2016/april/3_Conclusions_

recommendations_mini_IEAG_26_Feb2016_NewDelhi.pdf. Accessed May 12,

2016.

9. Report from GAVI to at SAGE on Immunization

October 2015. Available from

http://www.who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2015/october/Berkely_GAVI_SAGE_

October2015.pdf. Accessed May 13, 2016.

10. Joint Appraisal Report India 2015, Available from

http://www.GAVI.org/country/india/documents/#approve dproposal.

Accessed May 13, 2016.

11. Duintjer Tebbens RJ, Pallansch MA, Cochi SL,

Wassilak SGF, Linkins J, Sutter RW, et. al. Economic analysis of

the global polio eradication initiative. Vaccine 2011;29: 334-43.

12. Direct benefits of eradication and risks of polio

reintroduction. Available from www.polioeradication.org

http://www.polioeradication.org/Portals/0/Document/Resources/StrategyWork/PEESP_CH4_EN_US.pdf.

Accessed May 13, 2016.

13. Cochi SL, Hegg L, Kaur A, Pandak C, Jafari H. The

global polio eradication initiative: Progress, lessons learned, and

polio legacy transition planning. Health Aff. 2016;35:277-83.

|

|

|

|

|