After many years of battling

with poliomyelitis, India was finally declared polio-free in 2014 [1].

With an annual birth cohort of 27 million and a total 170 million

children below 5 to be reached in every polio round, this victory was

hard won and was a result of years of concerted efforts led by the

Government of India with strong support of partners and tireless efforts

by the millions of frontline workers [2]. India’s Polio program is a

remarkable public health achievement that overcame programmatic,

economic, social and cultural challenges by constantly innovating and

seeking out-of-the box solutions combined with unrelenting focus and

rigor that allowed the program to reach every child.

One of the innovation and major contributing factors

to the elimination of polio transmission in India was a social

mobilization network (SMNet) managed by UNICEF in the two States with

the highest burden; Uttar Pradesh (UP) and Bihar [3]. West Bengal has a

similar structure that started as an emergency preparedness response in

2011 in wake of the Howrah wild poliovirus (WPV) case.

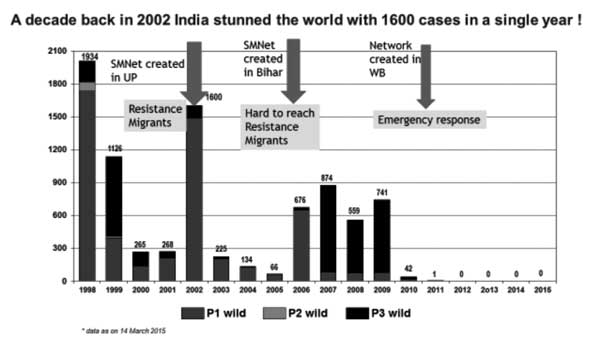

The decision to set up a social mobilization network

had its origins in the analysis of the epidemiological data of wild

poliovirus cases. An unprecedented outbreak in 2002 gave rise to 1600

polio cases. More than 80% of the polio cases in the world were in India

and 86% of WPV cases in India occurred in two States - Uttar Pradesh and

Bihar [4]. Further analysis revealed that over 59% of cases in Uttar

Pradesh belonged to the Muslim community, while according to 2001 census

Muslims comprise approximately 18% of the population in the State [5].

Data showed that a Muslim child was 5 times more likely not to receive

even one dose of OPV [5,6]. Studies and refusal analysis also showed

that there was deep rooted mistrust within the community that resulted

in misconceptions and refusals of OPV. Caregivers also complained about

the lack of trust in the health system and misbehavior of service

providers towards them [5,7,8].

This article is based on a review of primary and

secondary data sources that include SMNet MIS, various researches,

evaluations and technical reports, as well as working papers that

document communication efforts for polio eradication in India. NID/SNID

monitoring data was also reviewed and used. Other sources of information

analysed include country data presented at India Expert Advisory Group

(IEAG) meetings and Polio communi-cation reviews. Reports on Polio

eradication efforts in other countries were also reviewed.

This review examines social mobilization efforts for

polio eradication program in India with following objectives:

• To describe social mobilization strategies and

models which have resulted in polio eradication in India.

• To acknowledge the role of social and community

mobilizers in addressing community resistance and enhancing

community participation for improving public health programmes

through an enabling environment for immunization.

Polio Communication Challenges

The polio eradication campaign initially used a media

heavy approach through celebrity endorsements and branded IEC materials.

In the early stages, mass media was effective in reaching out to the

public - the early and late majority as defined by the Diffusion of

Innovations [9]. But despite the reach of the campaign, some resistant

pockets remained. These pockets tended to be reservoirs of not just

polio viruses but also circulating myths and misconceptions [8].

A social mobilization network was a felt need to

complement the communication activities being undertaken through mass

media channels and use of IEC materials. It was intended that a network

of community based mobilizers could be best suited to counsel and

convince resistant families to accept polio immunization. The mobilizers

had to be persons of trust from within the community who could open

closed doors and were acceptable locally [8].

The Social Mobilization Network (SMNet): Objectives

and Adaptive Models

The SMNet was conceived as a strategic mobilization

ground cadre that used the conventional principles of community

mobilization in an accelerated framework. It was first established in UP

in 2002 and then expanded to Bihar in 2005-06 with the objective of

increasing OPV uptake among children under 5 years of age in these

states. In West Bengal, following the last polio case in 2011, the SMNet

was established for emergency preparedness in response to the wild

poliovirus case in Howrah (Fig. 1) [10].

|

|

Fig. 1 Wild Polio Virus cases in India

and Social Mobilization Network [10] (Source- GOI/NPSP-WHO Polio

Update).

|

Apart from families that refused immunization, there

were other children who lacked access to services. Belonging to mobile,

migrant and hard to reach families, these were the missing children that

needed to be mapped and brought back into the polio immunization net.

The Social Mobilization Network (SMNet) thus gained shape as a cadre of

mobilizers that could strategically reach out to resistant or left out

families to ensure polio immunization.

Surveillance data were used to systematically map and

identify pockets of underserved and high risk areas/ groups to determine

areas for the SMNet operation. The selection of appropriate advocates

was based on negotiations and discussions with several implementing

partners as well as beneficiaries. The surveillance and supplementary

immunization activity (SIA) data provided case profiles, AFP non polio

cases, X marked houses and houses that reported no eligible children.

For example, a row of 10 or more houses reporting no eligible children

under the age of five were considered suspicious and eligible for

intensified mobilization and advocacy efforts. These were known as P0

(zero) houses, and during monitoring it was often seen that when in

clusters, most houses actually had children in them, indicating a silent

or passive refusal in that the houses did not reject the vaccine

outright but merely claimed to have no children. WHO then modified

monitoring analysis to capture this as a risk area.

In UP, the factors that contributed towards its high

polio burden included poor hygiene and sanitation with high rates of

diarrhea, a dense population with a high birth rate, low uptake of

breastfeeding, and resistance to vaccination among many of the Muslim

communities. Bihar contained pockets of resistance and the same

sanitation and health challenges, but an additional barrier in Bihar was

the difficult geographical terrain (i.e. the Kosi river basin,

which is prone to flooding), which leads to hard-to-reach populations

and migrants, including brick kiln and construction workers, and slum

dwellers [11].

The SMNet deploys community mobilizers in areas

identified as high risk to work with resistant communities and to

encourage uptake of the oral polio vaccine (OPV) during supplementary

immunization activities (SIA). The objectives are to:

• Maximize the impact of communication efforts at

the national state, district and block level through strengthened

coordination amongst partners and effective advocacy.

• Ensure that children most at risk -

particularly those under the age of two, Muslim and boys - are

adequately protected from polio by intensifying efforts in blocks

where wild polio virus (WPV) transmission is sustained.

• Increase the total number of children immunized

and turnout at the booth by achieving a critical mass of

communication activities in all high-risk areas of priority blocks

in states with on-going wild poliovirus transmission.

• Ensure polio eradication by strengthening

communication for routine immunization especially in polio-endemic

states.

Using a three tiered structure, the 7300 strong SMNet

works at district, block and community levels. The community mobilizer

coordinators (CMCs) of the SMNet belong to the communities that they

serve. Responsible for 350-500 households, they go house to house to

engage families through interpersonal communication and counseling

sessions - addressing myths and misconceptions and ensuring correct

knowledge about polio [12,13]. They also mobilize families before every

SIA round to ensure that all children below 5 years get OPV. Holding

mothers’ meetings and religious meetings to advocate for repeated polio

immunization, coordinating temple and mosque announcements and

conducting polio classes in schools, madrasas and other

congregations are just some of the mobilization activities that a CMC

regularly undertakes. In between rounds, they counsel families where

children were missed, tracking pregnant women, registering newborn and

tracking them for polio and routine immunization.

SMNet also includes strong supervisory structures at

block, district, division and state levels. Block mobilization

coordinators (BMCs) are for mentorship and supportive supervision of

CMCs (1 BMC per 10-15 CMCs); District mobilization coordinators (DMCs)

and District undeserved coordinators (DUCs) are responsible for

monitoring district level data and for forming partnerships;

Sub-Regional coordinators (SRCs) provide regional leadership and report

to the state level polio units.

The SMNet also reaches out to community assets to

extend their footprint – an army of 31,000 community influencers to

build trust and goodwill for the polio program while its 26,650

informers help notify movement of migrant communities. [12,13]. Today,

UNICEF’s SMNet reaches over 2.2 million under 5 children in some 3

million households of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and West Bengal [12, 13].

A. SMNet: Strategies that Delivered Results

SMNet focuses on reaching the most vulnerable,

migrant, mobile, underserved and marginalized children in high risk and

hard to reach communities using a range of strategies in response to the

data and evolving issues:

1. Underserved strategy

The underserved strategy was initially conceptualized

to actively reach Muslim populations and was later expanded from

including Muslim sub-sects to also including hard to reach and migratory

communities who had limited access to information or health services.

These included groups like nomads, brickkiln and construction workers,

slum dwellers etc. This strategy comprises both ground-up community and

social mobilization and a top down advocacy component. Religious leaders

and mosques were actively engaged to disseminate positive information

and address myths. Over 31,000 community influencers are regularly

tapped to build community trust and goodwill for the polio program while

some 26,650 informers help notify movement of migrant communities

[12,13]. These influencers help in mobilization and also accompany

vaccination teams during biphasic/ follow-up activities. Influencers

include religious leaders, doctors, rural medical practioners (RMPs),

shopkeepers and even housewives – each with their own perspectives and

experiences who are able to counsel resistant households for acceptance

[14].

2. Tracking of beneficiaries and high risk groups

WHO and UNICEF jointly identified 400,000 high risk

areas using specific criteria and some 17 indicators [14]. Community

mobilizers track immunization status of all 0-5 years old children and

pregnant women in these high risk areas with special focus on newborns

and guest children. The ‘X’ code used to mark missed households, has

been expanded to allow CMCs to identify the causes for not immunizing a

child. This has allowed a targeted strategy for converting ‘X’

households to households where all children have received OPV in the

current immunization round. CMCs also record information about these

beneficiaries and their immunization status in the field book.

3. Counseling and mobilization activities

CMCs visit every household before the polio round and

provide counseling focussing on previously resistant households. Each

CMC conducts monthly mothers’ meetings, Polio classes in schools,

children’s calling groups (bulwa tolis) and coordinates with

mosques and other institutions for regular announcements. The CMC is

also responsible for display of IEC materials during polio rounds

ensuring high visibility for the program.

4. Evidence based planning at block and district

level

Evidence based planning using real time monitoring

data is used to develop and update house-level microplans for tracking

the immunization progress of every single child. Communication micro

plans are developed at block and district level using evidence generated

through CMCs field book and monitoring data.

5. Capacity building and supportive supervision

The supportive supervisory structure provides

supportive supervision and handholding. These block and district level

mobilizers visit each CMC area on regular basis and mentor them, provide

on job training and jointly solve problems related to their job.

Refresher trainings ensure that the mobilizers are always updated with

the latest tools and techniques.

6. Monitoring and MIS management information

system (MIS)

UNICEF supports a robust monitoring system for polio

communication activities and social mobilization activities using many

indicators by various partners at the local, state and national level to

continually adapt plans and strategies, address bottlenecks and monitor

progress.

7. Strengthening routine immunization and

convergent health issues

The SMNet has been supporting polio end game

strategy, by focusing on routine immunization RI and other convergent

health issues. In addition to the polio messages, the SMNet mobilizers

dovetail convergent child survival messages on routine immunization,

exclusive breast feeding, ORS and zinc and handwashing at critical

times.

B. SMNet: Social Impact

At the core of SMNet lies co-opting the community.

The SMNet uses the members of the community to seed networks with

change. The acceptability of the CMC as she is a part of the community

that she seeks to change is key to the success of the SMNet. In the

context of India, with its socio-cultural complexities, this in itself,

is a mammoth and complex task requiring different approaches for

different groups. The SMNet also triggered sociological changes as

welcome by-products of the polio program and has proved to be an entry

point to larger social and health benefits:

1. Empowering women

Several women, in particular, those from minority or

underprivileged communities gained livelihoods and social confidence

through interacting with community members outside of their initially

circumscribed circumstances. Increased awareness, particularly of health

and hygiene issues has equipped them better not just to improve the

health and well-being of their own families, but also to champion these

in their communities.

2. Empowering children

In the traditional Indian social setup, children

usually do not have agency to act on their own. The SMNet programme,

through its bulawa tolis which co-opts children, has not only

helped them gain their voice, but also established the groundwork and

consciousness for their future participation in similar programs.

3. Mobile and migrant populations

Migrant populations have typically been the toughest

outreach category to access during any program. The SMNet has

established a network of informers conscious of their social

responsibilities and a process that allows migrant families access to

polio vaccines. The network can be further leveraged for several other

uses also – like other healthcare outreach programs, education etc.

4. Religious leaders

SMNet has served to create and intensify a larger

social, public role for religious leaders through their co-option into

the program. This should subsequently, not only broaden their role to

intensify a focus on public health, but also other social good programs

and serve as agencies for repudiating myths that form obstacles to

public health and development programs.

C. SMNet: Results

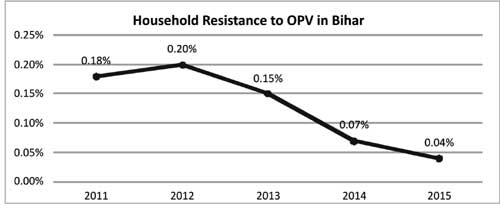

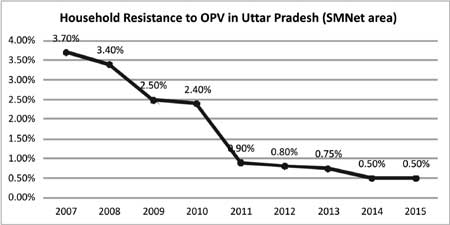

An independent assessment of SMNet in 2013 concluded

that it has been "effective and efficient" at achieving its goals of

increasing the total number of children immunized against polio and

ensuring that those most at risk are protected. Between 2007 and 2015,

resistant households declined 77% in Bihar and 86% in UP, where now less

than 0.5% of households resist vaccination (Fig. 2 and

3) [13,15].

|

|

Fig. 2 Household resistance to OPV in

Uttar Pradesh (SMNet Area) [13,15].

|

|

|

Fig. 3 Household resistance to OPV in

Bihar (SMNet Area) [13,15].

|

About 76% of the children less than five years of age

in CMC areas of Uttar Pradesh (no booth activity in Bihar) were

vaccinated at booths in every round, in comparison to this only 43% of

the children vaccinated at booth in non-CMC areas. The average number of

children vaccinated at booth was consistently above 268 in CMC area

almost double of non-CMC areas (148) [16].

Findings and analyses also suggested a high relevance

of the network, SMNet design and interventions are aligned with

community needs. The approach has been relevant to achieve the results

of the polio eradication program by reducing resistance to vaccination

and reaching the unreached in polio endemic states of UP and Bihar.

A value for money (VfM) analysis that was undertaken

in 2014 revealed that SMNet has utilized funds in an economical manner

and has indicated allocative efficiencies. The outputs of SMNet in terms

of coverage and unit costs indicate a cost-efficient and fairly

economical program. Forecasted costs of SMNet for the next decade

support a strong case for continuing eradication interventions as the

most cost-effective option [3].

Analysis of knowledge attitude, behavior and

practices (KABP) through a study for polio eradication, 2009 revealed

that the SMNet has led to consistent and significant increase in

knowledge attitude behaviour practices with the access of communities to

FLWs and CMC visits. (Meta-Analysis of KABP studies showed a strong

linear relationship (Correlation coefficient (r) =0.51 for KA and r=0.90

for BP [17].

D. SMNet: Replication and Similar Programs

The SMNet is already supporting routine immunization

program and other convergent health issues like diarrhea, handwashing

and exclusive breastfeeding – areas that converge with its core

programming. The polio program is naturally transitioning in scope

programmatically, geographically, financially and in its human resources

management. The Indian Government is already applying the polio assets

and learnings in routine immunization (RI) and other convergent

activities. Recognized by the global polio eradication initiative (GPEI)

for its effectiveness, SMNet has been replicated in other Indian states

and polio-endemic countries.

• Vertical health system strengthening model:

In Uttar Pradesh, a parallel outreach system was established to work

alongside and more intensively with government efforts considered

sub-scale (or even non-existent), similar to models applied in parts

of Pakistan, Nigeria and Afghanistan.

• HIV programming: In the context

of the complexities involved in the uptake of intervention services

in HIV prevention, particularly in Asia, social mobilization

evidence has demonstrated that service needs to be driven by people

rather than targets. An example is the shift in focus from "for the

community" to "by the community" the AVAHAN program by the Bill and

Melinda Gates Foundation which has been able to achieve a

significant increase in the uptake of condoms and reduction in STIs

[18].

• Sanitation in Odisha: Engagement with

the treatment villages targeted to increase routine latrine use and

acceptance was done through community mobilization, leveraging a

combination of shaming and subsidy techniques. Findings over the

baseline indicate a significant influence on routine latrine use and

acceptance [19].

• Immunization in Southern Sudan:

In the highly underserved county of Kajo Kenji, an accelerated

immunization program was carried out over three months with the goal

of doubling the county’s immunization coverage of 13% - this, within

a limited budget of USD 6000. In addition to radio spots, each field

supervisor was partnered with one community mobilizer who travelled

to churches, markets, and individual houses to inform the community

about the immunization campaign, using megaphones in some areas.

After the three month acceleration campaign, vaccine coverage

increased to 35.1%, up from 13.8% [20].

Conclusion and Way Forward

The SMNet made significant contributions to India’s

polio eradication by addressing community resistance. The network not

only helped in achieving in an accelerated time line, an impossible task

of interrupting transmission of polioviruses in high risk areas but also

seeded change in the communities. Community mobilizers helped bring

change by being a part of the change process themselves. Community

influencers, religious leaders, teachers, managers and other such

influential groups can be important allies in change. Human resource

management techniques and an ongoing capacity development can lead to

building up of social capital that can be harnessed for social change.

Vertical programs can be successfully expanded to convergent areas once

initial strategic objectives are achieved. And possibly the most

important universal take-away from the SMNet programme is that the

community trust is critical to the success of any behavior change

programs. Externally imposed agencies fail to bring about long term

change without the trust of the community and this trust can be built

only if the members of the network are integral to the community.

Contributors: ARS: conception and design of the

work; drafting the work; PS: drafting few sections; revising it

critically for important intellectual content; GT: drafting few

sections; revising it critically for important intellectual content.

Funding: None. Competing Interest: None

stated.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Updates on CDC’s Polio Eradication Efforts. Atlanta: Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention; 2016. Available from:

www.cdc.gov/polio/updates/updates-2016.htm . Accessed January 20,

2016.

2. United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). India’s

story of Triumph over Polio. India: United Nations Children’s Fund

(UNICEF); 2014; 12-13. Available from: www. iple.in/files/ckuploads/files/Polio_Book.pdf.

Accessed February 3, 2016.

3. Deloitte. Evaluation of Social Mobilization

Network (SMNet). India: United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF); 2014;

45, 68-81. Available from:

http://www.unicef.org/evaldatabase/files/India_2013-001_Evaluation_of_Social_Mobilization_Network_Final_

Report.pdf. Accessed February 3, 2016.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Morbidity and Mortality Report. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention; 2003, 52 (09); 172-175. Available from

http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5209a2.htm. Accessed

February 3, 2016.

5. United Nations Children’s Fund. When every child

counts- Engaging the Underserved Communities for Polio Eradication in

Uttar Pradesh, India. Regional Office for South Asia: United Nations

Children’s Fund; 2004. Available from

http://www.unicef.org/rosa/everychild.pdf. Accessed February 3,

2016.

6. India: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare,

World Health Organization-National Polio Surveillance Project. AFP

Surveillance Immunity gap data. New Delhi: Government of India; 2002.

7. Chaturvedi Gitanjali. The Vital Drop –

Communication for Polio Eradication in India. India: SAGE Publication;

2008. 96-8.

8. United Nations Children’s Fund. Critical Leap to

Polio Era-dication. Regional Office for South Asia: United Nations

Children’s Fund; 2003. Available from

www.unicef.org/rosa/critical.pdf. Accessed on February 5, 2016.

9. Everett M. Rogers. Diffusion of Innovations. 5th

ed. New York: The Free Press; 1984.

10. India: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare,

World Health Organization-National Polio Surveillance Project. Polio

Update. New Delhi: Government of India; 2015

11. Grassly N, LaForce M, Modlin J, Murthy N, Rohde

J, Sarma N, et al. Independent Evaluation of Major Barriers to

Interrupting Poliovirus Transmission in India; Report.

http://www.polioeradication.org/ ;2009. Available from:

www.polioeradication.org/content/general/Polio_ Evaluation_IND.pdf.

Accessed February 5, 2016.

12. United Nations Children’s Fund. Communication and

social mobilization to keep India Polio Free. India Country Office:

United Nations Children’s Fund; 2015. Available from:

www.iple.in/documents/download/3557. Accessed February 9, 2016.

13. United Nations Children’s Fund. SMNet MIS. India

Country Office: United Nations Children’s Fund, 2015.

14. United Nations Children’s Fund. Successful

Strategies for Stopping Polio in India-Overview of the key strategies;

India Country Office: United Nations Children’s Fund; 2015. Available

from: www.iple.in/documents/download/3555 . Accessed February 9,

2016.

15. India: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare,

Polio National Immunization Day (NID)/ Sub National Immunization Day

(SNID) data. New Delhi: Government of India; 2007-15.

16. India: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare,

Polio National Immunization Day (NID)/ Sub National Immunization Day

(SNID) data. New Delhi: Government of India; 2015.

17. United Nations Children’s Fund. Concurrent

Knowledge, Attitude, Behaviour and Practices (KABP) Study for Polio

Eradication. India Country Office: United Nations Children’s Fund; 2009.

18. Sarkar S. Community engagement in HIV prevention

in Asia: going from ‘for the community’ to ‘by the community’ – must we

wait for more evidence? Sexually Transmitted Infections, 2010; vol. 86,

no. 1, Available from:

www.uniteforsight.org/social-marketing/social-mobilization. Accessed

July 29, 2015.

19. Pattanayak SK, Yang JC, Dickinson KL, Poulos C,

Patil SR, Mallick RK, et al. Shame or subsidy revisited: social

mobilization for sanitation in Orissa, India. Bull World Health Organ.

2009; vol. 87, no. 8:580-7.

20. Makamba YT. Immunization Activities in

Post-Conflict Settings: Field Notes from Southern Sudan. The Journal of

Global Health. 2011. Available from:

www.ghjournal.org/immunization-activities-in-post-conflict-settings-field-notes-from-southern-sudan/.

Accessed on July 29, 2015.