|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2021;58:857-860 |

|

Zinc Supplementation for Prevention of

Febrile Seizures Recurrences in Children: A Systematic Review

and Meta-Analysis

|

|

Manish Kumar, 1 Swarnim

Swarnim2, Samreen Khanam3

From Department of Pediatrics, 1All India Institute of Medical

Sciences, Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh; 2Department of Pediatrics, Maulana

Azad Medical College, New Delhi; 3Guru Nanak Eye Center, Maulana Azad

Medical College, New Delhi.

Correspondence to: Dr Manish Kumar, Department of Pediatrics, All

India Institute of Medical Sciences, Kunraghat,

Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh 273 008.

Email:

[email protected]

Published online: August 02, 2020;

PII: S097475591600359

PROSPERO Registration Number: CRD42020190747

|

Background: Multiple studies have documented

lower serum zinc levels in patients with febrile seizures in comparison

to febrile patients without seizure. However, there is limited evidence

comparing the effects of zinc supplementation with placebo on recurrence

of febrile seizures in children. Objectives: To study the effects

of zinc supplementation on recurrence rate of febrile seizures in

children less than 60 months of age. Design: Systematic review

and meta-analysis of randomized and quasi-randomized controlled trials.

Data Source and selection criteria: We searched PubMed, EMBASE

and CENTRAL databases for articles reporting randomized or

quasi-randomized controlled trials comparing the effects of zinc

supplementation with placebo on recurrence of febrile seizures in

children aged less than 60 months. We performed a fixed effect

meta-analysis to provide pooled odds ratio of febrile seizure

recurrence. Quality of evidence was assessed using GRADE approach.

Participants: Children aged less than 60 months. Intervention:

Zinc supplementation Outcome measures: Odds of febrile seizure

recurrence. Results: Four clinical trials with a total of 350

children were included in the review. There was no statistically

significant difference between odds of febrile seizure recurrence during

one year follow up, in children on zinc supplementation compared to

those on placebo (OR 0.70; 95% CI 0.41 1.18, I2 = 0%). Conclusion:

Available evidence is very low quality and thus inadequate to make

practice recommendations.

Keywords: Epilepsy, Management, Outcome, Prevention,

Recurrence.

|

|

F

ebrile seizures are the most common

pediatric seizure disorder, primarily affecting children in the

age group of 6 months to 5 years, with a global prevalence of

2-5% [1]. The patho-physiology of febrile seizures is not well

understood and studies have identified various risk factors,

including family history, genetic factors, metabolic changes and

micronutrient deficiencies [2-5]. Putative role of zinc in the

pathogenesis of febrile seizures has been hypothesized [6-8]

with studies showing association of low zinc levels with higher

neuronal excitability through its interactions with multiple ion

channels and receptors [9-11]. A recent metanalysis found lower

serum zinc levels in patients with febrile seizure compared to

febrile cases without seizure [12]. However, there is limited

available evidence about the role of zinc supplementation in

prevention of febrile seizures recurrence, which this review

attempts to identify, appraise and synthesize.

METHODS

This systematic review has been conducted in

accordance to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews

and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [13] The protocol was

registered in the International Prospective Register of

Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) database.

Search strategy and search eligibility:

All authors independently searched the databases including

PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials,

from inception to 28 September, 2020. Details of the electronic

search strategy and the results are given as

Web Table I.

Cross references of all articles whose full text was screened,

was also checked to find additional articles.

Inclusion criteria were original articles, in

any language, having randomized or quasi-randomized controlled

trial design; population included children less than 60 months

of age; intervention studied was zinc supplementation;

comparator being placebo; and outcome being febrile seizure

recurrences during 1year follow-up.

Data extraction and quality assessment:

Data were extracted by all authors independently using a

pre-designed form. Any disagreements were resolved with

consensus. The recorded details included lead author, year of

publication, country, sample size, inclusion and exclusion

criteria, gender distribution, mean age, type of zinc salt, dose

of zinc, number of recurrences of febrile seizure in

intervention and control group, and duration of follow-up.

Quality of each study was assessed using the

criteria outlined in the Risk of bias tool in Cochrane handbook

for systematic reviews of interventions [14]. Quality of

evidence was assessed using Grading of Recommendations

Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach [15],

and summary of findings table was generated on GRADEpro GDT

software [16].

Statistical analysis: We performed a

fixed effect meta-analysis to provide pooled odds ratio of

febrile seizure recurrence. Pooled odds ratio (OR) with 95%

confidence interval (CI) was calculated for primary outcome.

Heterogeneity was assessed using the I² statistics.

Statistical analysis was performed using Review Manager version

5.4 [17]. .

RESULTS

Our search strategy yielded 132 articles and

one additional article was included after manual search. Finally

four articles with a total of 350 children were included in

qualitative synthesis [18-21] (Fig. 1). Table I

summarizes the characteristics of the included studies.

Three of the included studies are from Iran [18-20], while one

study was conducted in India [21]. One article was in Persian

with English abstract [18]. Age of the children included varied

across the studies. Studies by Fallah, et al. [19] and Kulkarni,

et al. [21] included children with normal anthropometric

measurements. Though zinc sulfate was used as intervention in

all the four studies, the doses differed across the studies. All

the studies had a follow-up of one year. While in the study by

Ahmedabadi, et al. [18] and Fallah, et al. [19], follow up was

conducted every three months, children enrolled in study by

Kulkarni, et al. [21] were followed up on a monthly basis.

|

|

Fig.1 PRISMA flow diagram

showing the study selection process.

|

Three studies (18,20,21) had high risk

of selection bias, performance bias and detection bias.

Web

Fig. 1 summarizes risk of bias for each included study and

Web Fig. 2 depicts risk of bias graph as percentages

across all studies. Publication bias was assessed with funnel

plot (Web Fig. 3); however, this analysis was limited by

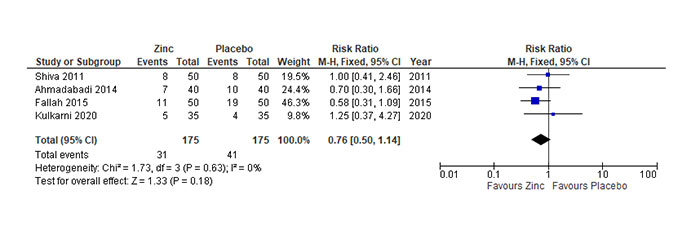

small number of included studies. The pooled odds of recurrence

of febrile seizure during one year follow up was less in

intervention group, though it was not statistically significant

(OR 0.70; 95% CI 0.41 1.18, I 2

= 0%).

Fig. 2

depicts the Forest plot for this outcome.

|

|

Fig. 2 Forest plot of effect of zinc

supplementation on rate of febrile seizure recurrence in

children less than 60 months of age.

|

The quality of evidence pooled from included

studies was assessed using GRADE approach and a summary of

findings table (Web Table II) was generated on GRADEpro

GDT software [16]. Due to inherent risk of bias of included

studies along with inconsistent and imprecise results from these

studies, the quality of evidence ranged from low to very low.

DISCUSSION

Available evidence from four

randomized/quasi-randomized trials, including a total of 350

children, did not find any significant difference between

recurrence rate of febrile seizure in children on zinc

supplementation compared to children on placebo.

However, there were differences across the

studies. While, Fallah, et al. [19] did not explain the reasons

for their assumption of such a large difference, while

calculating the sample size, the other three studies did not

mention their strategy for calculation of sample size. Further,

the study populations were not similar with respect to inclusion

and exclusion criteria. Age groups of children enrolled in

included studies had significant variation. Given the fact that

febrile seizures are an age-dependent phenomenon with reported

peak incidence between 1218 months [22], such variations may

have important ramifications in rate of febrile seizure

recurrences across studies. Also, evolving evidence suggests

that serum zinc level is lower in patients with febrile seizure

[12]. In this light, variation in dose of zinc supplementation

in intervention groups of the included studies can affect

febrile seizure recurrences. Three of the included studies are

on Iranian population, which may affect the generalizability of

results for other population group.

Though we searched large and representative

databases for this review, we recognize the limitation of not

having searched other databases. Available evidence pertaining

to zinc supplementation for prevention of febrile seizures is of

low to very low quality and thus inappropriate to make a

practice recommendation. Included trials were inadequately

powered with high risk of bias. Further research, in the form of

methodologically robust, multi-centric randomized controlled

trials, is needed.

Acknowledgement: Dr Niraj Kumar,

Additional Professor, Department of Neurology, AIIMS Rishikesh

for his inputs in drafting the manuscript.

Note: Additional material related

to this study is available with the online version at

www.indianpediatrics.net

Contributors: MK: conceptualized the

review, literature search, data analysis and manuscript writing;

SS: literature search, data analysis and manuscript writing; SK:

literature search, data analysis and manuscript writing. All

authors approved the final version of manuscript, and are

accountable for all aspects related to the study.

Funding: None; Competing interests:

None stated.

REFERENCES

1. Steering Committee on Quality

Improvement and Management, Subcommittee on Febrile Seizures

American Academy of Pediatrics. Febrile seizures: Clinical

Practice Guideline for the Long-Term Management of the Child

with Simple Febrile Seizures. Pediatrics. 2008;121:1281-6.

2. Audenaert D, Van Broeckhoven C, De

Jonghe P. Genes and loci involved in febrile seizures and

related epilepsy syndromes. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:391-401.

3. Kang J-Q, Shen W, Macdonald RL. Why

does fever trigger febrile seizures? GABAA receptor gamma2

subunit mutations associated with idiopathic generalized

epilepsies have temperature-dependent trafficking

deficiencies. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2590-7.

4. Dubé C, Vezzani A, Behrens M, et al.

Interleukin-1â Contributes to the Generation of Experimental

Febrile Seizures. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:152-5.

5. Reid AY, Galic MA, Teskey GC, Pittman

QJ. Febrile seizures: current views and investigations. Can

J Neurol Sci. 2009;36:679-86.

6. Reid CA, Hildebrand MS, Mullen SA, et

al. Synaptic Zn2+ and febrile seizure susceptibility. Br J

Pharmacol. 2017; 174:119-25.

7. Tütüncüoğlu S, Kütükçüler N, Kepe L,

et al. Proinflam-matory cytokines, prostaglandins and zinc

in febrile convulsions. Pediatr Int. 2001;43:235-9.

8. Hildebrand MS, Phillips AM, Mullen SA,

et al. Loss of synaptic Zn2+ transporter function increases

risk of febrile seizures. Sci Rep. 2015;5:17816.

9. Marger L, Schubert CR, Bertrand D.

Zinc: An under-appreciated modulatory factor of brain

function. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014;91:426-35.

10. Paoletti P, Vergnano AM, Barbour B,

Casado M. Zinc at glutamatergic synapses. Neuroscience.

2009;158:126-36.

11. Khosravani H, Bladen C, Parker DB, et

al. Effects of Cav3.2 channel mutations linked to idiopathic

generalized epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:745-9.

12. Heydarian F, Nakhaei AA, Majd HM,

Bakhtiari E. Zinc deficiency and febrile seizure: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Turk J Pediatr.

2020;62:347-58.

13. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et

al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews

and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare

interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ.

2009;339:b2700.

14. Assessing risk of bias in a

randomized trial. Accessed September 29, 2020. Available

from: https://training.

cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-08

15. RevMan. Accessed September 29, 2020.

Available from:

https://training.cochrane.org/online-learning/core-soft

ware-cochrane-reviews/revman

16. GRADE handbook. Accessed September

29, 2020. Available from:

https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/handbook/handbook.html

17. GRADEpro. Accessed September 29,

2020. Available from: https://gradepro.org/

18. Ahmadabadi F, Mirzarahimi M,

Samadzadeh M, et al. The efficacy of zinc sulfate in

prevention of febrile convulsion recurrences. J Isfahan Med

Sch. 2014;31:1910-8.

19. Fallah R, Sabbaghzadegan S, Karbasi

SA, Binesh F. Efficacy of zinc sulfate supplement on febrile

seizure recurrence prevention in children with normal serum

zinc level: A randomised clinical trial. Nutrition. 2015;31:

1358-61.

20. Shiva S, Barzegar M, Zokaie N, Shiva

S. Dose supple-mental zinc prevents recurrence of febrile

seizures? Iran J Child Neurol. 2011;5:11-4.

21. Kulkarni S, Kulkarni M. Study of zinc

supplementation in prevention of recurrence of febrile

seizures in children at a tertiary care center. MedPulse Int

J Pediatr. 2020;13:1-4.

22. Leung AK, Hon KL, Leung TN. Febrile seizures: an

overview. Drugs Context. 2018;7:21253.

|

|

|

|

|