|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2021;58:846-849 |

|

Long-Term Morbidity and Functional Outcome

of Japanese Encephalitis in Children: A Prospective Cohort

Study

|

|

Abhijit Dutta, 1

Shankha

Subhra Nag,1 Manjula Dutta,2

Sagar Basu3

From 1Department of Pediatric Medicine, North Bengal Medical College

and Hospital, Sushruta Nagar, Siliguri; 2Department of Microbiology,

School of Tropical Medicine, Kolkata; and 3Department of Neurology, KPC

Medical College and Hospital, Kolkata; West Bengal.

Correspondence to: Dr Shankha Subhra Nag, Embee Fortune, Flat No.

D3H, Near BSF Camp, Asian Highway 2, Kadamtala, Siliguri 734 011, West

Bengal.

Email: [email protected]

Received: December 10, 2020;

Initial review: January 27, 2021;

Accepted: May 15, 2021

Published online: May 20, 2021;

PII:S097475591600327

|

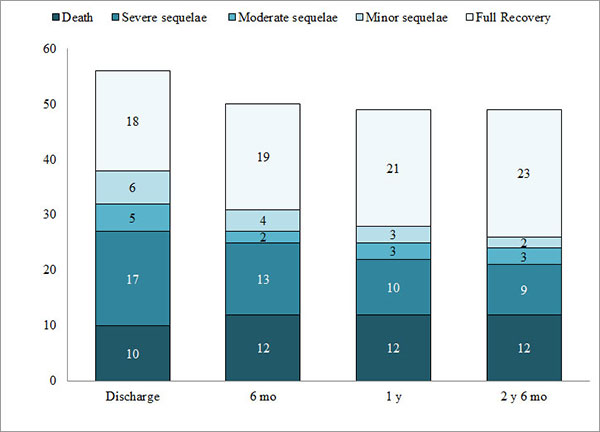

Objective: To describe the long term morbidity and functional

outcome of Japanese encephalitis in children. Methods:

Laboratory-confirmed Japanese encephalitis cases were enrolled in the

study from January, 2016 to September, 2017 and surviving cases were

prospectively followed up for 2.5 years to document various morbidities.

Outcome was functionally graded at discharge and during follow-up using

Liverpool outcome score. Results: Out of 56 children enrolled, 10

(17.9%) died during hospital stay; severe sequelae was observed in 17

(30.4%) at discharge. At the end of study, among 37 children under

follow-up, 23 (62.2%) recovered fully, 2 (5.4%) showed minor sequelae, 3

(8.1%) had moderate sequelae, and 9 (24.3%) were left with severe

sequelae. Common long term morbidities were abnormal behavior (n=10,

27%), post encephalitic epilepsy (n=8, 21.6%), poor scholastic

performance (n=8, 21.6%) and residual motor deficit (n=7,

18.9%). Improvement of morbidities was noted mostly within initial 1

year of follow-up. Conclusions: More than half of the Japanese

encephalitis survivors recovered fully, most within the first year after

discharge.

Keywords: Dystonia, Epilepsy, Movement disorder, Quadriplegia.

|

|

J apanese encephalitis

is considered a major public health problem due to its epidemic

potential, high case fatality rate up to 30%, and residual neuro-psychiatric

morbidities in 30-50% [1]. It continues to occur in endemic

areas of India, despite the introduction of the vaccine in

Universal immunization program in 2011 [2-4]. Quantification of

long term outcome and its classification in terms of extent of

disability is essential, so that the impact of the disease on

independent livelihood can be understood. There is paucity of

data regarding long term outcome of JE in children [5-7].

Therefore, this study was conducted to find out the magnitude of

morbidity and its evolution over time.

METHODS

This prospective cohort study was conducted

from January, 2016 to March, 2020 at a tertiary care teaching

hospital of eastern India, after obtaining clearance from the

institutional ethics committee. Children aged up to 12 years

admitted with acute encephalitis syndrome (AES) were subjected

to laboratory tests for detection of JE. Anti-JE IgM antibody

capture (MAC) ELISA was performed on cerebrospinal fluid and

serum samples using ELISA kit (NIV JE IgM Capture ELISA Kit,

version 1.5). Diagnosis of JE was confirmed by detection of

anti-JE IgM antibody in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), or both in

CSF and serum samples. Patients with positive results were

consecutively enrolled till September, 2017, after taking

informed consent from parents. They were managed as per standard

guideline including empirical broad spectrum antibiotics and

acyclovir, maintenances of fluid, electrolyte, acid-base balance

and euglycemia, management of raised intracranial pressure,

control of seizures, management of nosocomial infection and

other complications, and rehabilitation therapy [8]. Background

demographic and relevant clinical data and results of various

laboratory investigations including magnetic resonance imaging

(MRI) of brain were noted. Discharged patients were followed up

for two-and-a-half years at out-patient department and detailed

clinical examination was done to document clinical status. They

were provided with symptomatic and supportive management during

these visits. EEG was performed in children with history of

seizures either during hospital stay or during follow-up. After

documentation of full recovery, patients were kept under

telephonic follow-up till the end of the study.

Table I Morbidity Profile in Children With Japanese Encephalitis at Various Stages of Follow-up

| Morbidity |

At discharge (n=46) |

6 mo (n=38) |

1 y (n=37) |

2 y 6 mo (n=37) |

| Motor deficit |

21 (45.6) |

10 (26.3) |

7 (18.9) |

7 (18.9) |

|

Abnormal behaviora |

- |

18 (47.4) |

16 (43.2) |

10 (27.0) |

| Epilepsy |

18 (39.1) |

12 (31.6) |

12 (32.4) |

8 (21.6) |

|

Poor scholastic performanceb |

- |

12 (31.6) |

8 (21.6) |

8 (21.6) |

| Incoordination |

13 (28.3) |

2 (5.3) |

2 (5.4) |

2 (5.4) |

| Feeding problems |

13 (28.3) |

3 (7.9) |

3 (8.1) |

3 (8.1) |

| Dystonia |

12 (26.1) |

6 (15.8) |

2 (5.4) |

2 (5.4) |

| Dysarthria |

7 (15.2) |

2 (5.3) |

2 (5.4) |

2 (5.4) |

| Language difficulty |

9 (19.6) |

2 (5.3) |

2 (5.4) |

2 (5.4) |

| Urinary

incontinence |

5 (10.9) |

2 (5.3) |

2 (5.4) |

2 (5.4) |

| All values in no. (%).

Evaluation started at a1 mo or b3 mo of discharge. |

The Liverpool Outcome Score (LOS) [9,10],

previously validated in Indian children [11], was used in the

present study for functional grading of disability at discharge

and during follow-up. It assesses motor, cognition, self-care

and behavior using ten questions to parents or caregivers, and

observation of response to five simple motor tasks given to the

child. Outcome grading was assigned based on minimum score

obtained in any of the domains. Based on score obtained, LOS

classifies outcome as full recovery, minor sequelae, moderate

sequelae, severe sequelae, and death.

Statistical analysis: Descriptive

statistics were used. Data were analyzed using IBM Statistical

Package for Social Sciences version 20.0 (SPSS, IBM Corp).

RESULTS

A total of 194 children with features of AES

were screened, and 56 (28.8%) children (57.1% boys) were

diagnosed with laboratory confirmed JE during the study period.

Anti-JE IgM was detected in both CSF and serum in 44 children,

and in only CSF in another 12 children. Two children were below

1 year of age, 17 between 1-5 years and the rest between 5-12

years age group; median (IQR) age of study population was 6 year

3 month (5 year 10 month, 9 year 1 month). Most common clinical

features were fever (n=56, 100%), altered sensorium (n=51,

91.1%), seizures (n=36, 64.3%), signs of meningeal

irritation (n=27, 48.2%) and headache (n=21,

37.5%). Glasgow Coma Scale of 8 or less was observed among 12

children (21.4%) at admission. Median (IQR) duration of symptoms

before admission and duration of hospitalization was 3.5 (2,5)

days and 15.7 (11, 24.2) days, respectively. MRI of brain could

be performed in 38 children, of which 26 (68.4%) were abnormal.

Common sites of involvement were thalamus (n=22, 84.6%),

basal ganglia (n=16, 61.5%), cortex (n=12, 46.2%),

brainstem (n=9, 34.6%), medial temporal lobe (n=6,

23.1%) and cerebellum (n=2, 7.7%). Hemorrhagic lesion was

found in 3 children (11.5%) in addition to involvement of other

parts of brain; 2 had cerebral hemorrhage and 1 had subdural

hemorrhage. Ten cases (17.9%) died during the hospital stay. At

the time of discharge, 17 children (30.4%) had severe sequelae,

5 (8.9%) had moderate sequelae, 6 (10.7%) developed minor

sequelae, and 18 children (32.1%) showed full recovery as per

LOS.

At the end of 2 year 6 month of follow-up, we

observed full recovery among all children with minor sequelae.

Two out of 5 children categorized as moderate sequelae at the

time of discharge showed full recovery; 1 child improved and had

only minor sequelae. Two children with severe sequelae died

within 2 weeks of discharge. Of the 15 surviving patients with

severe sequelae, one improved considerably and had only minor

sequelae, three improved and were categorized as moderate

sequelae, and nine children remained as severe sequelae. Three

fully recovered children, and two children each from moderate

and severe sequelae group were lost to follow-up. At the

completion of the study, it was observed that among 37 children

remaining under follow-up, 23 (62.2%) had recovered fully and 14

(37.8%) were left with variable degrees of sequelae (Fig. 1).

|

|

Fig. 1 Sequelae at different

stages of follow-up in Japanese encephalitis affected

children.

|

Motor deficit was noted in 21 children

(45.6%) at discharge; quadriparesis in 14, hemiparesis in 6, and

monoparesis in one child. With rehabilitation therapy,

satisfactory motor improvement was noted in majority of children

(66.7%) within the first year of follow-up. Behavioral

abnormalities evolved fully at 1 month of discharge and were

noted among 24 children; predominant features were excessive

anger (n=12), irritability (n=8), aggressiveness (n=5),

sudden bouts of unexplained cry or laughter (n=3), and

irrelevant talking (n=1). Four children were unable to

recognize family members initially, and the problem persisted in

one of them. At the end of follow-up, abnormal behavior

persisted in 10 (27%) children.

In the acute phase of the disease, 36

children presented with seizures, mostly of generalized tonic-clonic

type; 17 of them needed two or more anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs).

EEG was performed in 26 children, 18 (69.2%) were abnormal.

These children were having recurrent seizures and AED was

continued during follow-up. Among 12 children receiving AEDs at

2 years, therapy was stopped in six as they were seizure free

with normal EEG, but two children had relapse of seizures after

stoppage of drugs, and therapy was restarted. Till the end of

the study, 8 children (21.6%) were on AED.

Among cases under follow-up, 23 children were

school-going. Poor scholastic performance was observed in 8

(21.6%) children in the long term; another 7 of them became

drop-outs due to motor deficits, behavioral problems and

apprehension of seizures. Dystonia was noted in 12 children

(26.1%) at the time of discharge, which improved substantially

within first 6-9 months. Two children showed persistence of

language problem, one with motor aphasia and another with global

aphasia. Feeding problems were seen predominantly in first 6

months of follow-up; mostly due to motor deficit,

in-coordination and abnormal behavior.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, 56 children diagnosed

with Japanese encephalitis were evaluated by Liverpool Outcome

Score which showed mortality of 17.9% and 30.4% with severe

sequelae at discharge. At the end of 2.5 year follow-up, 62.2%

children recovered fully and 37.8% children were left with

variable degree of sequelae.

Previous studies have reported a wide range

of mortality (8-25%) and severe sequelae (11-25%) with Japanese

encephalitis [5,6,12-15]. Subjective nature, and therefore lack

of uniformity of classification, and varying duration of

follow-up may be responsible for wide range of sequelae noted in

different studies. The various morbidities observed in our

cohort are in agreement with previous studies [5-7,13,14]. The

extent of improvement among different morbidities varied in our

study population. Few patients with poor clinical and

radiological features showed unexpected remarkable improvement

during follow-up. Whereas some survivors with severe sequelae

showed improvement of different morbidities; nevertheless they

could not be placed at better functional grading as some other

domains did not improve. In addition, residual neuro-psychiatric

problems prevented a significant proportion of children from

returning to normal life.

Only few studies have described long term

outcome of Japanese encephalitis affected children beyond 1

year, most probably due to remote residence of patients causing

difficulty in follow-up [5-7]. Improvement of morbidities was

noted mostly within initial 9-12 months of follow up, and there

was no noteworthy additional improvement afterwards. Previous

studies also shown majority of improvements within initial 6-12

months for most of the Japanese encephalitis survivors and neuro-logical

status at initial months of discharge was predictive of long

term outcome [5,6]. Some authors noted neurological

deterioration (microcephaly and hyper-active behavior) several

years after discharge in some survivors and suggested the need

for long term follow up [6]. However, we did not observe

worsening of neuro-psychiatric status in any child till the end

of follow up.

Relatively smaller sample size is a

limitation of the present study. Similarly, we were unable to

predict which category of children might improve and to what

extent. We suggest future studies to look into these aspects.

Considering high mortality and long term morbidities, preventive

aspects of the disease need to be prioritized.

Acknowledgements: Dr Sharmistha

Bhattacherjee, Department of Community Medicine, North Bengal

Medical College and Hospital, for helping with study design and

statistical analysis.

Ethics clearance: Institutional

Ethics Committee, North Bengal Medical College; No:

PCM/2015-16/603BK, dated December 30, 2015.

Contributors: AD: conception of the

study, acquisition of data and revising the manuscript for

important intellectual content. SSN: design of the study,

acquisition of data and drafting the manuscript; MD: acquisition

of data revising the manuscript for important intellectual

content; SB: interpretation of data and revising the manuscript

for important intellectual content. All the authors approved the

version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all

aspects of the work ensuring that questions related to the

accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately

investigated and resolved.

|

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS?

•

Nearly two-thirds of

survivors of Japanese encephalitis recover without any

sequelae.

•

Common long term morbidities observed are residual

motor deficits and abnormal behavior.

|

REFERENCES

1. World Health Organization. Japanese

Encephalitis. Accessed October 10, 2020. Available from:

https://www. who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/japanese-encephalitis

2. Directorate of National Vector Borne

Disease Control Programme- Delhi. State wise number of

AES/JE Cases and Deaths from 2014-2020 (till Sept). Accessed

October 10, 2020. Available from: https://nvbdcp.gov.in/WriteRead

Data/l892s/ 50863224041601897122.pdf

3. Gurav YK, Bondre VP, Tandale BV, et

al. A large outbreak of Japanese encephalitis predominantly

among adults in northern region of West Bengal, India. J Med

Virol. 2016; 88:2004-11.

4. Vashishtha VM, Ramachandran VG.

Vaccination policy for Japanese encephalitis in India: Tread

with caution! Indian Pediatr. 2015;52:837-9.

5. Baruah HC, Biswas D, Patgiri D, et al.

Clinical outcome and neurological sequelae in serologically

confirmed cases of Japanese encephalitis patients in Assam,

India. Indian Pediatr. 2002;39:1143-8.

6. Ooi MH, Lewthwaite P, Lai BF, et al.

The epidemiology, clinical features, and long-term prognosis

of Japanese encephalitis in central Sarawak, Malaysia,

1997-2005. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:458-68.

7. Ding D, Hong Z, Zhao SJ, et al.

Long-term disability from acute childhood Japanese

encephalitis in Shanghai, China. Am J Trop Med Hyg.

2007;77:528-33.

8. Sharma S, Mishra D, Aneja S, Expert

Group on Encephalitis, Indian Academy of Pediatrics.

Consensus Guidelines on Evaluation and Management of

Suspected Acute Viral Encephalitis in Children in India.

Indian Pediatr. 2012;49:897-910.

9. University of Liverpool Brain

Infections Group. Liverpool Outcome Score for Assessing

Children at Discharge. Accessed October 10, 2020. Available

from: https:// vaccineresources.org/details.php?i=676#:~:text=A%20

tool%20for%20doctors%20and,independent%20life%20

after%20Japanese%20encephalitis

10. University of Liverpool Brain

Infections Group. Liverpool Outcome Score for Assessing

Children at Follow–up. Accessed October 10, 2020. Available

from: https://vac cineresources.org/details.php?i=677.

11. Lewthwaite P, Begum A, Ooi MH, et al.

Disability after encephalitis: Development and validation of

a new outcome score. Bull World Health Organ.

2010;88:584-92.

12. Basumatary LJ, Raja D, Bhuyan D, et

al. Clinical and radiological spectrum of Japanese

encephalitis. J Neurol Sci. 2013;325:15-21.

13. Kakoti G, Dutta P, Ram Das B, et al.

Clinical profile and outcome of Japanese encephalitis in

children admitted with acute encephalitis syndrome. Biomed

Res Int. 2013;2013: 152656.

14. Maha MS, Moniaga VA, Hills SL, et al.

Outcome and extent of disability following Japanese

encephalitis in Indonesian children. Int J Infect Dis.

2009;13:e389-93.

15. Verma A, Tripathi P, Rai N, et al. Long-term outcomes and

socioeconomic impact of japanese encephalitis and acute

encephalitis syndrome in Uttar Pradesh, India. Int J Infect.

2017; 4:e15607.

|

|

|

|

|