|

clinicopathological conference |

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2016;53: 815-821 |

|

Recurrent

Ventricular Tachycardia and Peripheral Gangrene in a Young Child

|

|

*Kim Vaiphei, Pankaj C Vaidya, Pandiarajan Vignesh,

#Parag Barwad and Anju Gupta

From Departments of Pediatrics, *Histopathology and

#Cardiology, PGIMER, Chandigarh, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Pankaj C Vaidya, Associate

Professor, Department of Pediatrics, Advanced Pediatrics Centre (APC),

Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER),

Chandigarh 160 012, India.

Email: [email protected]

Received: December 23, 2105;

Accepted: April 09, 2016.

Published online: July 01, 2016. PII:S097475591600017

|

A 10-year-old girl presented with sudden onset recurrent ventricular

tachycardia and symmetrical distal peripheral gangrene. She also had

pulmonary thromboembolism and cerebral sinus venous thrombosis.

Investigations revealed anemia, hemolysis, hypocomplementemia, and

elevated IgM anti-beta2 glycoprotein antibody levels. Electrocardiogram

and echocardiogram suggested features of a rare cardiac anomaly, which

was confirmed at autopsy.

Keywords: Antiphospholipid antibodies (APLA), Arrythmogenic

right ventricular dysplasia (ARVD), Thromboembolic manifestations,

Ventricular tachycardia.

|

|

Ventricular tachycardia in children is a

life-threatening emergency that needs prompt recognition and treatment.

When immediate correctable causes like dyselectrolytemia and drug

overdosages are not found, underlying structural defects of the heart

need to be looked for [1]. Thromboembolic manifestations in a child with

ventricular tachycardia are more likely to be due to underlying cardiac

pathology. We describe a child with ventricular tachycardia and

extensive thromboembolic features, where the final autopsy yielded a

rare cardiac anomaly. The etiology of thrombus was not only cardiac but

also an associated thrombophilic condition.

Clinical Protocol

History: A 10-years-old girl presented with

intermittent fever and cough of 12 days duration. She started developing

pain and bluish discoloration of fingers and toes on day 3 of illness

which progressed over the next few days to involve bilateral hands and

feet. She started developing difficulty in breathing on day 8 of

illness. This was associated with decreased urine output and generalized

swelling beginning from lower limbs and progressing to abdomen and face.

She had altered sensorium in the form of irritability and incoherent

speech for three days prior to presentation. Past history and family

history were unremarkable. She was a product of non-consanguineous

marriage. Her four other siblings were alive and healthy.

Examination: Her anthropometry was normal. At

admission, she was noted to have increased work of breathing with

tachypnea (respiratory rate 30/min), tachycardia (heart rate 170/min),

prolonged capillary refill and cold peripheries. All peripheral pulses

were palpable but feeble. Blood pressure in right arm was 90/68 mm Hg.

She had gangrene and edema of all fingers and toes extending to dorsum

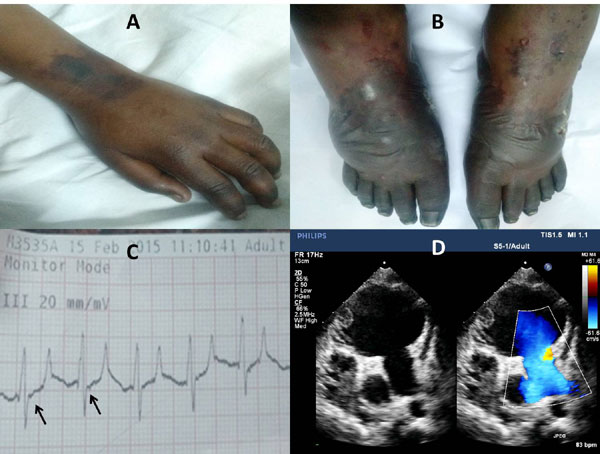

of hands and feet, respectively (Fig. 1a and 1b).

Pallor, periorbital puffiness and peripheral cyanosis were also noted.

Chest and cardiovascular examination revealed poorly localized apical

impulse, muffled heart sounds, S3 gallop and bilateral basal

crepitations. Soft, tender hepatomegaly with a span of 12 cm was also

found. She was conscious, oriented and obeyed commands but had

occasional aggressive behavior and incoherent speech. There were no

meningeal signs.

|

|

Fig. 1 (a and b) Upper and

lower limbs of the index child showing bilateral symmetric

distal gangrene (c) Electrocardiogram lead III of the index

child showing epsilon waves and tall p waves (d) B mode

echocardiography with doppler - apical four chamber view showing

grossly dilated right ventricle (RV) with sacculations and a RV

clot.

|

Course and management: At admission, she was

started on nasal prong oxygen support, and inotropic support for shock.

Immediate cardioversion was done for electrocardiogram (ECG) -proven

ventricular tachycardia. Low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) infusion

was started for peripheral gangrene. Chest X-ray revealed

cardiomegaly and counts showed polymorphonuclear leucocytosis,

normocytic anemia and thrombocytopenia (Table I).

Peripheral smear was suggestive of hemolysis and reticulocyte count was

8.14%. Serum lactate dehydrogenase was elevated to 1707.6 U/L (Normal:

140-280 U/L). Complement C3 and C4 levels were low at admission. Lung

perfusion scintigraphy suggested intermediate probability of pulmonary

thromboembolism. Initial coagulogram showed prolonged prothrombin time

(PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) with low

fibrinogen and elevated d-dimer values. Considering her age, sex,

thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia and low complements at admission, a

possibility of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) with antiphos-pholipid

antibody syndrome (APS) was considered and she was given intravenous

methylprednisolone at a dose of 30 mg/kg/day for 3 days.

TABLE I Blood Counts, Biochemistry and Coagulogram of the Index Child

|

Investigations |

Day1 |

Day6 |

Day 12 |

Day16 |

Day 19 |

|

Hemoglobin (g/dL) |

10.1 |

10.8 |

8.9 |

8.1 |

10.5 |

|

White cell counts (/mm3) |

16,400 |

17,800 |

19,600 |

14,400 |

11,300 |

|

Differential counts* |

P76,L20 |

P90,L06 |

P84,L11 |

P88,L08 |

P86,L10 |

|

Platelets (/mm3) |

63,000 |

88,000 |

1,13,000 |

94,000 |

1,40,000 |

|

Serum sodium/potassium (mEq/L) |

130/5.4 |

141/2.8 |

140/5.6 |

138/4.1 |

134/4.1 |

|

Blood urea/creatinine (mg%) |

149/1.0 |

29/0.5 |

40/0.6 |

48/0.9 |

45/0.5 |

|

Serum total proteins/albumin (g/dL) |

- |

5.2/2.7 |

6.2/3.8 |

6.1/3.8 |

7.0/3.5 |

|

Serum total/conjugated bilirubin (mg/dL) |

2.05/1.01 |

0.99/0.43 |

1.23/0.46 |

1.25/0.36 |

0.7/- |

|

Serum AST/ALT (U/L) |

- |

188/195 |

57/101 |

58/96 |

34/72 |

|

Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) |

- |

169 |

159 |

165 |

146 |

|

Serum calcium/phosphorous (mg/dL) |

- |

7.6/2.3 |

8.4/3.3 |

7.8 /2.7 |

8.7/2.3 |

|

C-reactive protein (mg/dL) |

58.5 |

12.6 |

6.5 |

66.8 |

- |

|

Prothrombin time (s) |

40 |

33 |

23 |

19 |

15 |

|

International normalized ratio |

2.8 |

2.3 |

1.7 |

1.3 |

1.1 |

|

APTT (s) |

40 |

39 |

48 |

32 |

30 |

|

Fibrinogen (mg/dL) |

- |

0.90 |

- |

- |

4.8 |

|

*P: Polymorphonuclear leucocytes %, L: Lymphocytes %; AST:

Aspartate transaminase, ALT: Alanine transaminase, APTT:

Activated partial thromboplastin time. |

Extensive infection work-up done during hospital stay

was not contributory. Immunological work up revealed immune complex

vasculitis in skin biopsy and elevated IgM anti-beta2 glycoprotein

antibody levels. Other investigations including procoagulant work-up are

summarized in Table II. Protein C, protein S, antithrombin

III levels and lupus anticoagulant activity could not be done as the

child was already on LMWH. Contrast enhanced Magnetic resonance imaging

(MRI) of the brain showed ill-defined hyperintense foci in bilateral

cerebral hemisphere that showed diffusion restriction suggestive of

ischemic foci of acute or subacute nature. MR venography of brain

revealed features of chronic sinus venous thrombosis in parietal region.

Epsilon waves were detected in subsequent ECGs done during hospital stay

(Fig. 1c). Severely dilated right atrium and

ventricle with sacculations and aneurysms of the right ventricle (RV)

were noted in the echocardiogram suggesting a diagnosis of

arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/ dysplasia (ARVC/D) (Fig.

1d). Clot was noted in RV with severe RV dysfunction. There

was no patent foramen ovale to explain systemic thrombo-embolic

tendency. There was no evidence of pulmonary arterial hypertension. On

day 9 of hospital stay, she developed recurrent episodes of ventricular

tachycardia needing repeated cardioversions and amiodarone infusion.

Permanent pacing or implantable defibrillator was planned and supportive

measures were continued. On day 20 of illness, she succumbed to

refractory ventricular tachycardia and cardiogenic shock.

TABLE II Investigations for Prothrombotic and Vasculitic Conditions in the Index Child

|

Investigations |

Results |

|

Radiology |

|

Lung perfusion scintigraphy |

Segmental wedge shaped mismatch defect in the right lower lobe–

intermediate probability of pulmonary thromboembolism |

|

Ultrasound doppler |

Normal flow demonstrated in both carotid, subclavian, axillary,

brachial, radial, renal, common femoral, popliteal, and anterior

tibial arteries. Flow could not be demonstrated in posterior

tibial arteries. |

|

CE-MRI* Brain with MRA* and MRV* |

MRV* showed obliterated straight sinus/proximal transverse

sinuses with venous collaterals in high parietal region ?

sequelae of chronic sinovenous thrombosis. MRA*- normal. |

|

Immunology |

|

Anti-nuclear antibody by IIF*, anti-double stranded DNA, anti-neutrophil

cytoplasmic antibodies by IIF*, anti-cardiolipin antibodies |

Negative |

|

Serum complements-C3/ C4 levels |

47/ 4 (Normal C3- 50 to 150 mg/dL, C4- 20 to 50 mg/dL) |

|

Anti- b2 glycoprotein 1 antibodies |

IgG- 2.8 U/mL, IgM- 11.6 U/mL (Normal <5 U/mL) |

|

Skin immunofluorescence |

IgM patchy band noted in blood vessels. IgG, IgA, C3 negative. |

|

Infectious diseases |

|

Blood cultures |

Sterile- repeated thrice |

|

Tuberculosis work up |

Negative (Tuberculin testing, gastric aspirates for AFB*

staining × 3) |

|

IgM Mycoplasma, IgM EBV VCA*, IgM CMV*, |

|

|

IgM anti-Hepatitis C, HIV* serologies |

Negative |

|

Hepatitis B surface antigen |

Negative |

|

Hematology |

|

Direct Coombs test |

Negative for C3d and IgG |

|

Peripheral smear for sickling, factor V Leiden mutation,

|

Negative |

|

flow cytometry based immuno-phenotyping for PNH* |

|

|

Serum homocysteine levels |

7.22 micromol/ L (Normal- 4.6 to 8.1) |

|

*CE-MRI: Contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging,

MRV-Magnetic resonance venography, MRA-Magnetic resonance

arteriography, IIF-Indirect immunofluorescence, AFB-Acid fast

bacilli, EBV VCA-Epstein Barr virus viral capsid antigen, CMV-

Cytomegalovirus, HIV-Human Immunodeficiency Virus,

PNH-Paroxysmal Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria. |

Unit’s final diagnosis: ARVC/D with RV failure,

RV clot and pulmonary embolism, ? Underlying prothrombotic condition, ?

Infection related or immune vasculitis, Disseminated intravascular

coagulation (DIC).

Clinical Discussion

The index child had features of cardiac involvement

(RV failure, ventricular tachycardia and shock) and thrombotic

manifestations at admission. In view of distinct right sided

cardiomyopathy with sacculations, ventricular tachycardia and epsilon

waves in ECG, diagnosis of ARVC/D appears likely [2-5]. Pulmonary

embolism and RV clots could be explained by right sided cardiac

pathology.

The index child had thrombotic manifestations both in

systemic and peripheral circulation- pulmonary embolus, symmetrical

peripheral gangrene and chronic sinovenous thrombosis on brain imaging.

She also had features of DIC- thrombocytopenia and prolonged PT and aPTT.

Recurrent ventricular tachycardia due to ARVC/D resulting in systemic

hypoperfusion and gangrene could explain symmetric peripheral gangrene.

However, it is impossible to explain preterminal febrile illness,

hemolysis, MRI evidence of chronic sinovenous thrombosis and low

complement levels with this diagnosis. Hence, thrombophilia (congenital

and acquired) is a strong possibility. Coming to the inherited

thrombophilias, serum homocysteine levels were normal and factor V

Leiden mutation was negative. Other inherited thrombophilias are protein

C deficiency, protein S deficiency, anti-thrombin deficiency,

dysfibrino-genemia, factor VIII mutations or prothrombin gene mutation,

for which the child could not be evaluated antemortem. The index child

had elevated IgM anti-beta2 GP1 antibody levels which may point to APS.

APS is an important acquired risk factor for both arterial and venous

thromboses. However, diagnosis of APS requires evidence of thrombosis

with elevated antibody titers (one of the three: lupus anticoagulant

(LA), anti-cardiolipin antibody (ACA), anti-beta2 GP1 antibody) on two

occasions at least 12 weeks apart. Diagnosis of catastrophic APS (CAPS)

requires demonstration of small vessel thrombotic manifestations of at

least three organs occurring within a week. APS is also known to cause

cardiomyopathy by causing multiple small vessel thrombosis and this is

one of the most important causes of death in APS [6,7].

Etiology of APS could be primary or secondary to

infections, autoimmune causes and malignancy. Extensive infectious

disease panel did not reveal any underlying infections. When we look at

autoimmune causes, the index child had two clinical criteria (hemolytic

anemia and thrombocytopenia) and two laboratory criteria (low

complements and elevated IgG anti-beta2 GP1 titres), which fulfils the

Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC 2012) criteria

for diagnosis of SLE. She also had evidence of immune complex mediated

vasculitis in skin biopsy. However, ANA and anti-dsDNA were negative,

making this diagnosis less likely.

Hypocomplementemia, immune complex mediated

vasculitis and embolic phenomenon can occur in infective endocarditis;

however, multiple blood cultures were sterile so this possibility does

not seem likely. The preterminal febrile illness with DIC, hemolysis and

low complement levels could be explained by an immune- or

infection-related vasculitis. So our final diagnosis would be

• Right sided cardiomyopathy ?ARVC/D ?APS related

• Pulmonary thromboembolism: related to RV

cardiomyopathy

• Systemic thrombotic manifestations ?APS related

Open Forum

Pediatric Rheumatologist: There is no going away

from the diagnosis of ARVC/D in this child as the index child had

refractory ventricular tachycardia and multiple sacculations and

dilatations of RV in echocardiogram. Histopathology of the heart may

show fibrofatty replacement of RV myocardium [2]. Though the clot in the

RV can explain the pulmonary embolism, the index child had features of

systemic microvascular/venous thrombosis, which prompted a procoagulant

work-up.

Adult Physician: The lesions in the extremities

are like purpura fulminans. The condition looks like CAPS and there may

be multiple thrombi in the cerebral, renal and extremity veins though

ARVC/D appears to be the primary heart disease.

Adult Rheumatologist: CAPS looks highly likely as

all the events in the index child occurred within a week.

Pediatric Rheumatologist 2: ARVC/D is distinctly

rare in pediatric population. Primary APS which caused the coronary

thrombosis and changes in RV appears more likely here.

Immunopathologist 1: Skin is the largest organ in the

body and looking at its biopsy helps in making diagnosis. We had a very

faint band test with occasional IgM deposits in the vessels suggestive

of immune complex vasculitis. I feel that APS related vasculitis is

likely in this child.

Pediatrician 1: Given the typical ECG and echo

findings, there is no doubt in the diagnosis of ARVC/D. This child

developed recurrent episodes of ventricular tachycardia which ultimately

took away the child. Pulmonary embolism can be explained by ARVC/D

itself; however to explain past sinovenous thrombosis and symmetric

peripheral gangrene with preserved pulses, prothrombotic state was

thought of. Preterminal illness could be infection related vasculitis.

Pediatrician 2: Index child fulfilled the SLICC

criteria for diagnosis of lupus. Yet, I think this child did not have

lupus as there was absence of ANA positivity by indirect immuno-fluorescence

testing on human cell lines. Though a question of semantics, strictly

speaking, we cannot use the term APS here because to call it as a

syndrome, we should repeat the antibody testing after 12 weeks [6].

Radiologist 1: What we found striking was the

enlarged veins in the posterior fossa that can be due to collaterals due

to chronic sinovenous thrombosis.

Adult physician 2: If cardiac MRI was done in

this child, it could have picked up the fibrofatty changes of the

myocardium in ARVD.

Cardiologist: We are dealing with two conditions:

procoagulant state and ARVC/D. Myocardial infarction related to right

coronary artery cannot cause such huge dilation of right atrium (RA) and

RV. Dilatation of RV secondary to pulmonary embolus is also less likely

as there was low pressure tricuspid regurgitation.

Adult Rheumatologist 2: This child had

symmetrical peripheral gangrene, low fibrinogen and prolonged PT and

aPTT. This looks more like DIC triggered by an infection which had a

focus in the heart like an infected clot.

Chairperson: There is no doubt that this child

had gangrene which was predominantly related to smaller vessels as the

peripheral pulses were palpable and this would bring in the possibility

of pro-coagulant disorders. Pathologist may clarify whether right heart

changes are related to the primary heart disease or it is secondarily

involved.

Pathology Protocol

A complete autopsy was carried out and the prosector

noted gangrene of both feet.

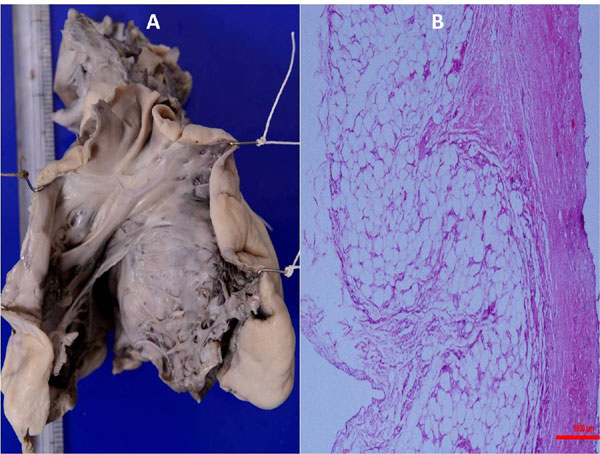

The heart weighed 208 g (normal range for this age

65-122 g) and was grossly enlarged. There was gross dilatation of the

right auricle, RA and RV with fresh auricular thrombus. RV anterior wall

was papery thin with marked endocardial sclerosis (Fig. 2a).

Histology of the RV myocardium confirmed the gross thinning (just about

one mm) and replacement by collagenized tissue with dense

collagenisation of the endocardium with abundant elastic tissue

deposition and degeneration of cardiac myocytes (Fig. 2b).

Remaining RV myocardium was discoloured due to ischemic myonecrosis.

There were multiple mural thrombi both in RA and RV. Endocardium

overlying the interventricular septum along outflow tract of RV was

thickened and it also showed collagenisation. Pulmonary valve and artery

were dilated. Left atrium was of normal morphology. Left ventricle (LV);

however, was hypertrophied and discolored. Aortic valves, aorta and

coronaries were within normal limits. Histology of LV myocardium showed

diffuse subendocardial myocyto-lysis, sparse inflammatory cell

infiltration and focal myofibre disarray. Sections studied from the

atrio-ventricular (AV) nodal system showed total collagenisation. No

thrombus was identified in intra-abdominal or intra-thoracic vessels.

|

|

Fig. 2 (a) Gross photograph of

the right side of the heart along the outflow tract showing

grossly thinned out right ventricular anterior wall and

endocardial sclerosis overlying the interventricular septum and

(b) Low power photomicrograph of the anterior right ventricular

wall showing totally fibrotic myocardium with no visible

myocardial fibres and thickened and elastisized endocardium. The

red coloured scale measure 1000 micron. (H&E, ×50).

|

Liver weighed 1032 g (normal range for this age

422-574 g) indicating gross enlargement. Capsular and cut surfaces of

the liver were grossly nodular and mottled due to bile staining. Normal

lobular architecture was lost and there was centro-central and

occasional centro-portal bridging fibrosis with many complete and

incomplete regenerative nodules. There was prominent centrizonal

sinuosoidal dilatation and congestion along with intra-sinusoidal

collagenisation. Larger sized portal tracts showed multiple dilated

intercommunicating portal venous channels. The scarred areas showed

deposition of excess hemosiderin pigment deposition.

Lungs showed evidences for aspiration and pulmonary

thromboembolism. Histology revealed pulmonary edema and fresh

intra-alveolar hemorrhages. Kidneys were swollen with marked medullary

congestion. Microscopic examination showed acute tubular necrosis and

granular, red blood cell and proteinaceous casts. Glomeruli and blood

vessels were within normal limits. There were multiple enlarged lymph

nodes in hilar, peri-pancreatic and mesentery regions measuring 10-15

mm. Sections showed reactive lymphoid follicles and sinus histiocytosis

with erythrophagocytosis. The spleen was of normal weight, and histology

showed depleted lymphoid follicle and evidence of extra-medullary

hematopoiesis in the sinusoids. The gastrointestinal tract (GIT) showed

mild mucosal congestion and histology showed changes of reflux

esophagitis and diffuse submucosal fibrosis along the entire length of

the intestine. The remaining organs were within normal limits.

Post-mortem bone marrow showed normal to mild hypercellularity with

presence of all the three hematopoietic cell lineages.

Final Autopsy Diagnosis

• Heart: ARVC/D associated with AV node fibrosis

and fresh mural thrombi of RA and RV

• Liver: Chronic passive venous congestion with

diffuse nodular regenerative hyperplasia

• Lungs: Pulmonary edema, thromboemboli and

aspiration.

• Kidneys: Acute tubular necrosis.

• GIT: Reflux esophagitis with diffuse

sub-mucosal fibrosis.

Open Forum

Immunopathologist 2: Most of the patients with

ANA negative lupus are positive for anti-Ro and anti-La, and even Hep2

cells can sometimes fail to detect these antibodies, sometimes

necessitating ELISA. These autoantibodies are known to cause heart

blocks and the pathology had shown fibrosed AV node. The index child

could have had this condition and the mother might be tested for those

antibodies.

Chairperson: It is beyond doubt that the child

had primary heart disease (ARVC/D). Distal gangrene cannot be explained

completely by the heart disease alone unless there was a communication

between right and left side, which has been negated by autopsy findings.

DIC precipitated by a different event or APS might have played part in

the presentation. The platelet counts never went below 80,000 cells/mm 3,

which is a little unusual for purpura fulminans.

Adult physician 1: Are the changes in ARVD due to

apoptosis or due to infiltration with inflammatory cells?

Pathologist: Apoptosis is part of the

degenerative process and especially in the pediatric age group, one

related condition - Uhl’s anomaly should be considered in the

differential diagnosis of RV failure and enlarged RV in echocardiogram.

However, the pathology is not suggestive of the same.

Discussion

ARVC/D is a cardiomyopathy characterized by

anatomical and functional abnormalities of predominantly RV. Genetic

origin is found in 30-50% individuals and is most commonly inherited as

autosomal dominant trait. Disease pathogenesis results from dysfunction

of desmosomes which are essential for electric conductivity and

contractility of myocardium. Most patients are men and it usually

presents between the ages of 20 and 40 [2]. In a large autopsy series of

ARVC/D, only 13% of cases were identified at less than 18 years [3].

Clinical phenotype evolves over a period of time. Common clinical

presentations are syncope, palpitations and ventricular tachycardia.

Arrhythmias are primarily a result of re-entry electrical circuits

generated from fibrofatty tissue in ARVC/D and can be triggered by

adrenergic stimulation such as exercise. Moreover, arrhythmias in ARVC/D

tend to be refractory to drugs [4]. Sudden death can be an initial

manifestation. In a large autopsy series of 1400 unexplained sudden

cardiac deaths, 200 (10.4%) cases had ARVC/D [3]. In the same series,

most cases of ARVC/D had abnormal Bundle of His and its branches because

of fat or fibrous tissue infiltration [3]. Disease progression in ARVD

might occur as periodic bursts rather than a continuous process. Disease

exacerbations can sometimes lead to life-threatening arrhythmias.

Definitive diagnosis of ARVC/D requires

histopathological demonstration of fibrofatty replacement of RV

myocardium. Expert consensus criteria requires either two major

criteria, one major plus two minor criteria or four minor criteria from

different groups for diagnosis (Table III) [4,5]. Index

child had histopathologically confirmed ARVC/D and many other features

of the consensus criteria.

Thromboembolic phenomena are observed in 4% of

patients with ARVD and it predominantly occurs in the right heart cavity

and pulmonary circulation [8]. Systemic thromboembolism in this

condition has been reported in only a few case reports [9,10].

Attenhoffer, et al. [9] reported a 36 year-old-woman with ARVC/D

and multiple large vein thromboses, where prothrombin gene mutation

G20210A was identified.

Anti-phospholipid antibodies (APLA) are identified in

4.2% of pediatric patients with thrombosis and it is the commonest

autoimmune etiology for acquired hyper-coagulable state [6].

Pathogenesis of thrombosis in APS is mainly due to activation of

platelets, monocytes and endothelium along with complement cascade

trigger by APLA. Around 50% of APS in children are associated with

autoimmune conditions, especially SLE [7]. Nearly 20% of patients with

primary APS can develop features of SLE in follow up. Presence of APS is

considered as a significant predictor for organ damage and mortality in

lupus patients [11]. Presence of LA correlates more with the

thromboembolic events in APS than the ACA or anti-beta2 GP1 assay.

Though anti-beta2 GP1 antibodies are more specific for thrombosis than

ACA, elevated titers of IgG anti-beta2GP1 antibody are much more

specific than elevated IgM which was observed in the index child [12].

Transient elevations of APLA are also found in association with various

infections and malignancies [13].

References

1. Pfammatter JP, Paul T. Idiopathic ventricular

tachycardia in infancy and childhood. J Am Coll Cardiol.

1999;33:2067-72.

2. Marcus F, Towbin JA. The mystery of arrhythmogenic

right ventricular dysplasia / cardiomyopathy. Circulation.

2006;114:1794-5.

3. Tabib A, Loire R, Chalabreysse L, Meyronnet D,

Miras A, Malicier D, et al. Circumstances of death and gross and

microscopic observations in a series of 200 cases of sudden death

associated with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy and/or

dysplasia. Circulation. 2003;108: 3000-5.

4. Gemayel C, Pelliccia A, Thompson PD.

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol.

2001;38:1773-81.

5. Basso C, Corrado D, Marcus FI, Nava A, Thiene G.

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Lancet.

2009;373:1289-300.

6. Ahluwalia J, Sreedharanunni S, Kumar N, Masih

J, Bose SK, Varma N, et al. Thrombotic primary antiphospholipid

syndrome: The profile of antibody positivity in patients from North

India. Int J Rheum Dis. 2014 Oct 8. [Epub ahead of print] doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.12479.

7. Avcin T, Cimaz R, Silverman ED, Cervera R,

Gattorno M, Garay S, et al. Pediatric antiphospholipid syndrome:

clinical and immunologic features of 121 patients in an international

registry. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e1100-07.

8. Wlodarska EK, Wozniak O, Konka M,

Rydlewska-Sadowska W, Biederman A, Hoffman P. Thromboembolic

complications in patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular

dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Europace. 2006;8: 596-600.

9. Attenhoffer Jost CH, Bombeli T, Schrimpf C,

Oechlin E, Kiowski W, Jenni R. Extensive thrombus formation in the right

ventricle due to a rare combination of arrhythmogenic right ventricular

cardiomyopathy and heterozygous prothrombin gene mutation G20210 A.

Cardiology. 2000;93:127-30.

10. Basso C, Thiene G, Corrado D, Angelini A, Nava A,

Valente M. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Dysplasia,

dystrophy, or myocarditis? Circulation. 1996;94:983-91.

11. Descloux E, Durieu I, Cochat P, Vital-Durand D,

Ninet J, Fabien N, et al. Paediatric systemic lupus erythematosus:

prognostic impact of antiphospholipid antibodies. Rheumatology (Oxford).

2008;47;183-7.

12. De Groot PG, Urbanus RT. The significance of

autoantibodies against b2-glycoprotein

I. Blood. 2012;120:266-74.

13. Kratz C, Mauz-Körholz C, Kruck H, Körholz D, Göbel U. Detection

of antiphospholipid antibodies in children and adolescents. Pediatr

Hematol Oncol. 1998;15:325-32.

|

|

|

|

|