|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2011;48:

709-717 |

|

Revised Statement on Management of Urinary

Tract Infections |

|

Indian Society of Pediatric Nephrology

Correspondence to: Dr M Vijayakumar, Department of

Pediatric Nephrology,

Mehta Children’s Hospitals, Chennai 600 031, India.

Email: [email protected]

|

Justification: In 2001, the Indian Pediatric Nephrology Group

formulated guidelines for management of patients with urinary tract

infection (UTI). In view of emerging scientific literature, the

recommendations have been reviewed.

Process: Following a preliminary meeting in

November 2010, a document was circulated among the participants to arrive

at a consensus on the evaluation and management of these patients.

Objectives: To revise and formulate guidelines on

management of UTI in children.

Recommendations: The need for accurate diagnosis of

UTI is emphasized due to important implications concerning evaluation and

follow up. Details regarding clinical features and diagnosis, choices and

duration of therapy and protocol for follow up are discussed. UTI is

diagnosed on a positive culture in a symptomatic child, and not merely by

the presence of leukocyturia. The need for parenteral therapy in UTI in

young infants and those showing toxicity is emphasized. Patients with

aysmptomatic bacteriuria do not require treatment. The importance of bowel

bladder dysfunction in the causation of recurrent UTI is highlighted.

Infants with the first UTI should be evaluated with micturating

cystourethrography. Vesicoureteric reflux (VUR) is initially managed with

antibiotic prophylaxis. The prophylaxis is continued till 1 year of age in

patients with VUR grades I and II, and till 5 years in those with higher

grades of reflux or until it resolves. Patients and their families are

counselled about the need for early recognition and therapy of UTI.

Children with VUR should be followed up with serial ultrasonography and

direct radionuclide cystograms every 2 years, while awaiting resolution.

Siblings of patients with VUR should be screened by ultrasonography.

Children with renal scars need long term follow up on yearly basis for

growth, hypertension, proteinuria, and renal size and function.

Key words: Child, India, Prevention, Urinary tract infections,

Vesicoureteric reflux.

|

|

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is a common bacterial infection in infants

and children. The risk of having a UTI before the age of 14 years is

approximately 1-3% in boys and 3-10% in girls [1,2]. The diagnosis of UTI

is often missed in infants and young children, as urinary symptoms are

minimal and often non-specific. Rapid evaluation and treatment of UTI is

important to prevent renal parenchymal damage and renal scarring that can

cause hypertension and progressive renal damage [3]. Pediatricians should

be aware of the clinical features, diagnosis, management and evaluation of

children with UTI. Even a single confirmed UTI should be taken seriously,

especially in young children, due to the potential for renal parenchymal

damage.

An Expert Group Meeting of the Indian Society of

Pediatric Nephrology was held on 12 th

November, 2010 in Kolkata to review the guidelines published in Indian

Pediatrics in 2001 [4]. New evidence was analyzed, with an aim to

update and revise the guidelines. The revisions are highlighted in

Table I.

TABLE I Major Revisions in This Document

-

The importance of urine culture on a

correctly collected specimen is reemphasized. The diagnosis of

urinary tract infection (UTI) must be based on a positive urine

culture.

-

Patients with UTI should be evaluated for the

presence of complications, underlying anomalies or voiding

dysfunction.

-

Recommendations on imaging following the

first episode of UTI are revised. Detailed investigations are

done in infants. In older children, micturating

cystourethrography is done in those who show abnormalities on

ultrasonography and DMSA scintigraphy.

-

Patients with recurrent UTI and/or

vesicoureteric reflux should be evaluated for bowel bladder

dysfunction.

-

Patients with grades I and II reflux should

receive antibiotic prophylaxis till they are 1 year old. Those

with higher grades of reflux are given prophylaxis till 5 years

of age, or longer in case of bowel bladder dysfunction or

breakthrough UTI.

|

Definitions

Infection of the urinary tract is identified by growth

of a significant number of organisms of a single species in the urine, in

the presence of symptoms. The diagnosis of UTI should be made only in

patients with a positive urine culture, since this has implications for

detailed evaluation and follow up. Recurrent UTI, defined as the

recurrence of symptoms with significant bacteriuria in patients who have

recovered clinically following treatment, is common in girls. Recurrent

UTI add to parental anxiety, medical costs and the risk of renal

parenchymal damage in young infants.

Clinical Features

UTI is an important cause for fever without a focus,

especially in children less than 2 years old [5,6]. In neonates, UTI is

usually a part of septicemia and presents with fever, vomiting, lethargy,

jaundice and seizures. Infants and young children present with recurrent

fever, diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal pain and poor weight gain. Older

children show fever, dysuria, urgency, frequency and abdominal or flank

pain. Adolescents may have symptoms restricted to the lower tract, and

fever may not be present.

The distinction between upper and lower UTI is

difficult and not necessary. In view of risks of renal parenchymal damage

associated with delayed treat-ment, UTI in children is considered to

involve the upper tract and should be treated promptly. Patients with

features of systemic toxicity are considered as having complicated UTI,

while those without these features are referred to as simple UTI (Table

II) [4]. This distinction has implications for therapy, as is

discussed later.

| Significant bacteriuria |

Colony count of >105/mL of a single

species in a midstream clean catch sample. |

| Asymptomatic bacteriuria |

Significant bacteriuria in the absence of symptoms of

urinary tract infection (UTI). |

| Simple UTI |

UTI with low grade fever, dysuria, frequency, and

urgency; and absence of symptoms of complicated UTI. |

| Complicated UTI |

Presence of fever >39ºC, systemic toxicity, persistent

vomiting, dehydration, renal angle tenderness and raised creatinine. |

| Recurrent infection |

Second episode of UTI. |

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of UTI is based on positive culture of a

properly collected specimen of urine. While urinalysis enables a

provisional diagnosis of UTI, a specimen must be obtained for culture

prior to therapy with antibiotics [7].

Significant pyuria is defined as >10 leukocytes per mm 3

in a fresh uncentrifuged sample, or >5 leukocytes per high power field in

a centrifuged sample. Leukocyturia might occur in conditions such as

fever, glomerulonephritis, renal stones or presence of foreign body in the

urinary tract. The detection of leukocyturia in absence of significant

bacteriuria is not sufficient to diagnose a UTI. Rapid dipstick based

tests, which detect leukocyte esterase and nitrite, are useful in

screening for UTI. A combination of these tests has moderate sensitivity

and specificity for detecting UTI, and is diagnostically as useful as

microscopy [1].

Collection of specimen for culture

A clean-catch midstream specimen is used to minimize

contamination by periurethral flora. Contamination can be minimized by

washing the genitalia with soap and water. Antiseptic washes and forced

retraction of the prepuce are not advised. In neonates and infants, urine

sample is obtained by either suprapubic aspiration or transurethral

bladder catheterization. Both techniques are safe and easy to perform [7].

The urine specimen should be promptly plated within one

hour of collection. If delay is anticipated, the sample can be stored in a

refrigerator at 4ºC for up to 12-24 hours. Cultures of specimens collected

from urine bags have high false positive rates, and are not recommended.

A urine culture should be repeated in case

contamination is suspected, e.g., mixed growth of two or more

pathogens, or growth of organisms that normally constitute the

periurethral flora (lacto-bacilli in healthy girls; enterococci in infants

and toddlers). The culture should also be repeated in situations where UTI

is strongly suspected but colony counts are equivocal. The number of

bacteria required for defining UTI depends on the method of urine

collection (Table III) [2,4,5].

TABLE III Criteria For The Diagnosis of UTI

|

Method of collection |

Colony count |

Probability of infection |

| Suprapubic aspiration |

Any number of pathogens |

99% |

| Urethral

catheterization |

>5 × 104 CFU/mL |

95% |

| Midstream clean catch |

>105 CFU/mL |

90-95% |

|

CFU: colony forming units. |

Initial Evaluation

The patient is examined for the degree of toxicity,

dehydration and ability to retain oral intake. The blood pressure should

be recorded and history regarding bowel and bladder habits elicited. The

child is examined for features that suggest an underlying functional or

urological abnormality (Tables IV and V). Complete

blood counts, serum creatinine and a blood culture should be done in

infants and children with complicated UTI.

TABLE IV Features Suggesting Underlying Structural Abnormality

| Distended bladder |

| Palpable, enlarged kidneys |

| Tight phimosis; vulval synechiae |

| Palpable fecal mass in the colon |

| Patulous anus; neurological deficit in lower limbs |

| Urinary incontinence |

| Previous surgery of the urinary tract, anorectal

malformation or meningomyelocele |

Table V Features Suggestive of Bowel Bladder Dysfunction

| Recurrent urinary tract infections |

| Persistent high grade vesicoureteric reflux |

| Constipation, impacted stools |

| Maneuvers to postpone voiding (holding maneuvers,

e.g., Vincent curtsy, squatting) |

| Voiding less than 3 or more than 8 times a day |

| Straining or poor urinary stream |

| Thickened bladder wall >2 mm |

| Post void residue >20 mL |

| Spinning top configuration of bladder on micturating

cystourethrogram |

Immediate Treatment

The patient’s age, features suggesting toxicity and

dehydration, ability to retain oral intake and the likelihood of

compliance with medication(s) help in deciding the need for

hospitalization. Therapy should be prompt to reduce the morbidity of

infection, minimize renal damage and subsequent complications.

Children less than 3 months of age and those with

complicated UTI should be hospitalized and treated with parenteral

antibiotics. The choice of antibiotic should be guided by local

sensitivity patterns. A third generation cephalosporin is preferred (Table

VI). Therapy with a single daily dose of an aminoglycoside may be

used in children with normal renal function [8]. Once the result of

antimicrobial sensitivity is available, the treatment may be modified.

Intravenous therapy is given for the first 2-3 days followed by oral

antibiotics once the clinical condition improves.

TABLE VI Antimicrobials for Treatment of UTI

| Medication |

Dose, mg/kg/day |

| Parenteral |

| Ceftriaxone |

75-100, in 1-2 divided doses IV |

| Cefotaxime |

100-150, in 2-3 divided doses IV |

| Amikacin |

10-15, single dose IV or IM |

| Gentamicin |

5-6, single dose IV or IM |

| Coamoxiclav |

30-35 of amoxicillin, in 2 divided doses IV |

| Oral |

| Cefixime |

8-10, in 2 divided doses |

| Coamoxiclav |

30-35 of amoxicillin, in 2 divided doses |

| Ciprofloxacin |

10-20, in 2 divided doses |

| Ofloxacin |

15-20, in 2 divided doses |

| Cephalexin |

50-70, in 2-3 divided doses |

Children with simple UTI and those above 3 months of

age are treated with oral antibiotics (Table VI). With

adequate therapy, there is resolution of fever and reduction of symptoms

by 48-72 hours. Failure to respond may be due to presence of resistant

pathogens, complicating factors or noncompliance; these patients require

re-evaluation.

Duration of Treatment

The duration of therapy is 10-14 days for infants and

children with complicated UTI, and 7-10 days for uncomplicated UTI [4, 5].

Adolescents with cystitis may be treated with shorter duration of

antibiotics, lasting 3 days [1]. Following the treatment of the UTI,

prophylactic antibiotic therapy is initiated in children below 1 year of

age, until appropriate imaging of the urinary tract is completed.

Supportive Therapy

During an episode of UTI, it is important to maintain

adequate hydration. A sick, febrile child with inadequate oral intake or

dehydration may require parenteral fluids. Routine alkalization of the

urine is not necessary. Paracetamol is used to relieve fever; therapy with

non steroidal anti- inflammatory agents should be avoided. A repeat urine

culture is not necessary, unless there is persistence of fever and

toxicity despite 72 hours of adequate antibiotic therapy.

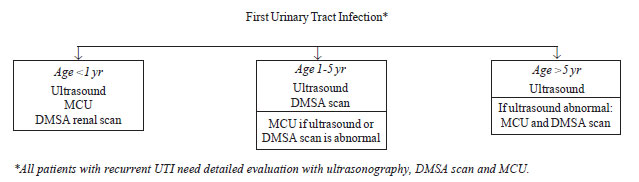

Evaluation after the first UTI

The aim of investigations is to identify patients at

high risk of renal damage, chiefly those below one year of age, and those

with VUR or urinary tract obstruction. Evaluation includes ultrasonography,

dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) renal scan and micturating

cystourethrography (MCU) performed judiciously as shown in Fig.

1. An ultrasonogram provides information on kidney size, number and

location, presence of hydronephrosis, urinary bladder anomalies and

post-void residual urine. DMSA scintigraphy is a sensitive technique for

detecting renal parenchymal infection and cortical scarring. MCU detects

VUR and provides anatomical details regarding the bladder and the urethra.

Follow-up studies in patients with VUR can be performed using direct

radionuclide cystography.

|

|

Fig. 1 Evaluation following initial urinary

tract infection. MCU: micturating cystourethrogram; DMSA

dimercaptosuccinic acid. |

There is limited evidence that intensive imaging and

subsequent management alters the long-term outcome of children with reflux

nephropathy diagnosed following a UTI. With availability of antenatal

screening, most important anomalies have already been detected and managed

after birth. Therefore, there is considerable debate regarding the need

and intensity of radiologic evaluation in children with UTI [1,9].

The Expert Group reviewed the current literature,

keeping in view that in our country the diagnosis of UTI is often missed

or delayed, and there are limitations of infrastructure and scarcity of

resources for routine antenatal screening. Based on the above, it

concluded that all children with the first UTI should undergo radiological

evaluation. The detection of significant scarring, high grade VUR or

obstructive uropathy might enable interventions that prevent progressive

kidney damage in the long-term. Since infants and young children are at

the highest risk for renal scarring, it is necessary that this group

undergo focused evaluation.

It is recommended that all infants with UTI be screened

by ultrasonography, followed by MCU and DMSA scintigraphy. Since older

patients (1-5 year old) with significant reflux and scars or urinary tract

anomalies are likely to show abnormalities on ultrasonography or

scintigraphy, a MCU is advised in patients having abnormalities on either

of the above investigations. Children older than 5 years are screened by

ultrasonography and further evaluated only if this is abnormal.

It is emphasized that patients with recurrent UTI at

any age should undergo detailed imaging with ultrasonography, MCU and DMSA

scintigraphy.

Ultrasonography should be done soon after the diagnosis

of UTI. The MCU is recommended 2-3 weeks later, while the DMSA scan is

carried out 2-3 months after treatment. An early DMSA scan, performed soon

after a UTI, is not recommended in routine practice. Patients showing

hydronephrosis in the absence of VUR should be evaluated by diuretic

renography using 99mTc-labeled

diethylenetriamine-pentaacetic acid (DTPA) or mercaptoacetylglycine

(MAG-3). These techniques provide quantitative assessment of renal

function and drainage of the dilated collecting system.

Prevention of Recurrent UTI

General

Adequate fluid intake and frequent voiding is advised;

constipation should be avoided [2,5]. In children with VUR who are toilet

trained, regular and volitional low pressure voiding with complete bladder

emptying is encouraged. Double voiding ensures emptying of the bladder of

post void residual urine. Circumcision reduces the risk of recurrent UTI

in infant boys, and might therefore have benefits in patients with high

grade reflux [10,11].

Bowel bladder dysfunction

Children presenting with recurrent UTI or persistent

VUR often have an associated voiding disorder, which are characterized by

abnormal patterns of micturition in presence of intact neuronal pathways

without congenital or anatomical abnormalities. Abnormal bladder pressure

and urinary stasis predispose these children to recurrent UTI. There may

be an abnormality either during the filling phase as in an overactive

bladder, or the evacuation phase as in dysfunctional voiding [12]. Since

constipation is often associated with a functional voiding disorder,

the condition is referred to as Bowel bladder dysfunction (BBD). Children

with recurrent UTI are likely to have dysfunctional voiding [5,13].

Features suggestive of voiding disorders are shown in Table V.

Evaluation for a voiding disorder includes a record of

frequency and voided volume and fluid intake for two to three days. It is

useful to watch the urinary stream, and for post void dribbling in boys.

Urodynamic studies are done in selected cases. The management of voiding

disorders should be carried out in collaboration with an expert. This

includes the exclusion of neurological causes, institution of structured

voiding patterns and management of constipation. In patients with an

overactive bladder, therapy with anticholinergic medications (e.g.,

oxybutinin) is effective. Patients with bowel bladder dysfunction and

large post void residues, benefit from timely voiding, bladder retraining,

and clean intermittent catheterization.

Antibiotic Prophylaxis

Long-term, low dose, antibacterial prophylaxis is used

to prevent recurrent, febrile UTI (Table VII). The

antibiotic used should be effective, non-toxic with few side effects and

should not alter the growth of commensals or induce bacterial resistance

[14].

TABLE VII Antimicrobials for Prophylaxis of Urinary Tract Infections

|

Medication |

Dose, mg/kg/day |

Remarks |

|

Cotrimoxazole |

1-2* |

Avoid in infants <3 mo, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency |

|

Nitrofurantoin |

1-2 |

May cause vomiting and nausea; avoid in infants <3 mo, G6PD

deficiency, renal insufficiency |

|

Cephalexin |

10 |

Drug of choice in first 3-6 mo of life |

|

Cefadroxil |

5 |

An alternative agent in early infancy |

|

Usually given as

single bedtime dose; *of trimethoprin. |

Indications and Duration of Prophylaxis

The indications and duration of prophylaxis depend on

patient age and presence or absence of VUR. Antibiotic prophylaxis is

recommended for patients with (i) UTI below 1-yr of age,

while awaiting imaging studies, (ii) VUR (see Table VIII),

(iii) frequent febrile UTI (3 or more episodes in a year) even if

the urinary tract is normal [14, 15]. Antibiotic prophylaxis is not

advised in patients with urinary tract obstruction (e.g., posterior

urethral valves), urolithiasis and neurogenic bladder, and in patients on

clean intermittent catheterization.

TABLE VIII Management of Vesicoureteric Reflux

| VUR grade |

Management |

| Grades I and II |

Antibiotic prophylaxis until 1 yr old. Restart

antibiotic prophylaxis if breakthrough febrile UTI. |

| Grades III to V |

Antibiotic prophylaxis up to 5 yr of age. Consider

surgery if breakthrough febrile UTI. |

| |

Beyond 5 yr: Prophylaxis continued if there is bowel

bladder dysfunction. |

Breakthrough UTI on Prophylactic Antibiotics

Breakthrough UTI results either from poor compliance or

associated voiding dysfunction. The UTI should be treated with appropriate

antibiotics. A change of the medication being used for prophylaxis is

usually not necessary. There is no role for cyclic therapy, where the

antibiotic used for prophylaxis is changed every 6-8 weeks.

Asymptomatic Bacteriuria

Asymptomatic bacteriuria is the presence of significant

bacteriuria in the absence of symptoms of UTI. Its frequency is 1-2% in

girls and 0.2% in boys [1]. Asymptomatic bacteriuria is a benign

condition, which does not cause renal injury and requires no treatment.

The organism isolated in most instances is E. coli, which is of low

virulence. Eradication of these organisms is often followed by symptomatic

infection with more virulent strains. Therapy of asymptomatic bacteriuria

or antibiotic prophylaxis is not required [1].

The presence of asymptomatic bacteriuria in a patient

previously treated for UTI should not be considered as recurrent UTI.

Vesicoureteric Reflux

VUR is seen in 40-50% infants and 30-50% children with

UTI, and resolves with age. Its severity is graded using the International

Study Classification from grade I to V, based on the appearance of the

urinary tract on MCU [16]. Lower grades of reflux (grade I-III) are more

likely to resolve. Secondary VUR is often related to bladder outflow

obstruction, as with posterior urethral valves, neurogenic bladder or a

functional voiding disorder.

The presence of moderate to severe VUR, particularly if

bilateral, is an important risk factor for pyelonephritis and renal

scarring, with subsequent risk of hypertension, albuminuria and

progressive kidney disease. The risk of scarring is highest in the first

year of life [17]. The presence of intrauterine VUR has been associated

with renal hypoplasia or dysplasia [18].

Therapy for Primary VUR

Over the last decade it has been increasingly

recognized that not all children with VUR benefit from diagnosis or

treatment. In some patients the reflux is innocuous and self limiting. In

others, VUR is accompanied with renal damage that has an onset during the

intrauterine period with dysplastic kidneys at birth, where the treatment

of VUR will not change the long term outcome [18]. There is a subset of

children who would benefit from treatment; however, identifying this group

of patients remains a challenge.

Conventional therapy for VUR includes antibiotic

prophylaxis and surgical intervention [11, 19, 20]. A recent systematic

review on patients with dilating reflux concluded that the outcomes

following surgical repair versus prophylaxis were similar in terms

of the number of breakthrough UTI and risk of renal scarring [20].

Experts recommend that the management of patients with VUR should depend

on the patient age, grade of reflux and whether there are any breakthrough

infections [11].

The proposed guidelines for management of VUR are

outlined in Table VIII. It is recommended that patients

should initially receive antibiotic prophylaxis while awaiting spontaneous

resolution of VUR. A close follow up is required for occurrence of

breakthrough UTI. Repeat imaging is required after 18-36 months in

patients with grade III-V VUR. Radionuclide cystogram, with lower

radiation exposure, has higher sensitivity for detecting reflux and is

therefore preferred for follow-up evaluation. Since the risk of recurrent

UTI and renal scarring is low after 4-5 years of age [11, 21], it is

advised that prophylaxis be discontinued in children older than 5 years

with normal bowel and voiding habits, even if mild to moderate reflux

persists.

While evidence from few studies suggests that the

strategy of prompt diagnosis and treatment of UTI might be as effective as

antibiotic prophylaxis [1,22], this approach requires validation in

controlled trials. The clinician should discuss the benefits and risks of

withholding antibiotic prophylaxis with the parents [19, 20].

Patients with grade III to V reflux may be offered

surgical repair if they have breakthrough febrile UTI, if parents prefer

surgical intervention to prophylaxis, or in patients who show

deterioration of renal function [20,21]. An evaluation for voiding

dysfunction (based on history, voiding diary) should be done before

surgery. Antibiotic prophylaxis is continued for 6 months after surgical

repair.

The availability of dextranomer/hyaluronic acid

copolymer (Deflux) endoscopic treatment has been proposed as an

alternative to surgical repair for patients with VUR [23]. While results

are satisfactory in surgeons experienced with the procedure, a significant

proportion of patients, particularly those with bowel bladder dysfunction,

may show persistence and/or recurrence of reflux and progressive renal

damage [24,25]. In view of limited prospective randomized controlled

trials, the use of endoscopic correction is currently not recommended as

first line therapy [11].

Screening of siblings and offspring

Reflux is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner

with incomplete penetrance; 27% siblings and 35% offspring of patients

show VUR [26]. Ultrasonography is recommended to screen for the presence

of reflux. Further imaging is required if ultrasonography is abnormal [11,

26].

Long Term Follow-up

Patients with a renal scar (reflux nephropathy) are

counseled regarding the need for early diagnosis and therapy of UTI and

regular follow up. Physical growth and blood pressure should be monitored

every 6-12 months, through adolescence. Investi-gations include urinalysis

for proteinuria and estimation of blood levels of creatinine. Annual

ultrasound examinations are done to monitor renal growth.

TABLE IX Indication for Referral to a Pediatric Nephrologist

|

• |

Recurrent urinary tract infections |

|

• |

Urinary tract infections in association with bowel bladder

dysfunction |

|

• |

Patients with vesicoureteric reflux |

|

• |

Underlying urologic or renal abnormalities |

|

• |

Children with renal scar, deranged renal functions, hypertension |

Indications for a referral to a Pediatric Nephrologist

UTI can be effectively managed by the primary care

physician. However because of their potential for renal parenchymal

damage, scarring and subsequent chronic kidney disease, patients having

risk factors that increase the likelihood of complications should be

managed in collaboration with an expert (Table IX).

Writing Committee: M Vijayakumar, M Kanitkar, BR

Nammalwar and Arvind Bagga.

Acknowledgment: The Committee acknowledges the

contributions of A Sinha, S Uthup, P Hari, A Iyengar, A Pahari, M Shah and

S Banerjee.

Participants of the Expert Group Meeting held on 12

November 2010 at Kolkata: Aditi Sinha, Anand S Vasudev, Arpana

Iyengar, Arvind Bagga, Ashima Gulati, BR Nammalwar, H Lekha, Indira

Agarwal, Jayati Sengupta, Jyoti Sharma, Kamini Mehta, Kishore Phadke,

Kumud P Mehta, Madhuri Kanitkar, Manoj G Matnani, Madhusmita Sengupta,

Mehul Shah, Pankaj Hari, Prabha Senguttuvan, Prahlad N, Premalatha, Preeti

Shanbag, RN Srivastava, Sanjeev Gulati, Saroj K Patnaik, Sidharth K Sethi,

Susan Uthup, Tamilarasi V, Tathagata Bose, Uma S. Ali, Vijayakumar M (convener),

Vinay K Agarwal and VK Sairam.

References

1. National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and

Children’s Health. Urinary tract infection in children diagnosis,

treatment and long-term management. RCOG Press, London 2007. Available

from www.rcpch.ac.uk/Research/ce/Clinical-Audit/Urinary-Tract-Infection,

Accessed on 17 March, 2011.

2. Chang SL, Shortliffe LD. Pediatric urinary tract

infections. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2006;53:379-400.

3. Smellie JM, Prescod NP, Shaw PJ, Risdon RA, Bryant

TN. Childhood reflux and urinary infection: a follow-up of 10–41 years in

226 adults. Pediatr Nephrol. 1998;12:727-36.

4. Indian Pediatric Nephrology Group. Consensus

statement on management of urinary tract infections. Indian Pediatr.

2001;38:1106-15.

5. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Quality

Improvement, Subcommittee on Urinary Tract Infections. Practice

parameters: The diagnosis, treatment and evaluation of the initial urinary

tract infections in febrile infants and young children. Pediatrics.

1999;103:843-52.

6. Nammalwar BR, Vijayakumar M, Sankar J, Ramnath B,

Prahlad N. Evaluation of the use of DMSA in culture positive UTI and

culture negative acute pyelonephritis. Indian Pediatr. 2005;42:691-6.

7. Srivastava RN, Bagga A. Urinary tract infection.

In: Pediatric Nephrology, 5th edn. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers; 2011.p.

273-300.

8. Bloomfield P, Hodson EM, Craig JC. Antibiotics for

acute pyelonephritis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

2003;3:CD003772.

9. Lim R. Vesicoureteral reflux and urinary tract

infection: evolving practices and current controversies in pediatric

imaging. Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:1197-1208.

10. Singh-Grewal D, Macdessi J, Craig J. Circumcision

for the prevention of urinary tract infection in boys: a systematic review

of randomized trials and observational studies. Arch Dis Child.

2005;90:853-8.

11. Peters CA, Skoog SJ, Arant BS, Copp HL, Elder JS,

Hudson RG, et al; American Urological Association Education and

Research, Inc. Summary of the AUA guideline on management of primary

vesicoureteral reflux in children. J Urol. 2010;184:1134-44.

12. Nevéus T, von Gontard A, Hoebeke P, Hjälmås K,

Bauer S, Bower W, et al. The standardization of terminology of

lower urinary tract function in children and adolescents: report from the

standardization committee of the International Children’s Continence

Society. J Urol. 2006;176:314-24.

13. Ramamurthy HR, Kanitkar M. Recurrent urinary tract

infection and functional voiding disorders. Indian Pediatr.

2008;45:689-91.

14. Mangiarotti P, Pizzini C, Fanos V. Antibiotic

prophylaxis in children with relapsing urinary tract infections: review. J

Chemother. 2000;12:115-23.

15. Dai B, Liu Y, Jia J, Mei C. Long-term antibiotics

for the prevention of recurrent urinary tract infection in children: a

systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95:499-508.

16. Lebowitz RL, Olbing H, Parkkulainen KV, Smellie JM,

Tamminen-Mobius TE. International system of radiographic grading of

vesicoureteric reflux: International Reflux Study in Children. Pediatr

Radiol. 1985;15:105-9.

17. Ylinen E, Ala-Houhala M, Wikstrom S. Risk of renal

scarring in vesicoureteral reflux detected either antenatally or during

the neonatal period. Urology. 2003;61:1238-42.

18. Craig JC, Irwig LM, Knight JF, Roy LP. Does

treatment of vesicoureteric reflux in childhood prevent end-stage renal

disease attributable to reflux nephropathy? Pediatrics. 2000;105:1236-41.

19. Williams GJ, Lee A, Craig JC. Long-term antibiotics

for preventing recurrent urinary tract infection in children. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev. 2006;3:CD001534.

20. Hodson EM, Wheeler DM, Smith GH, Craig JC,

Vimalachandra D. Interventions for primary vesicoureteric reflux. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev. 2007;3:CD 001532.

21. Greenbaum LA, Mesrobian HGO. Vesicoureteral reflux.

Pediatr Clin North Am. 2006;53:413-27.

22. Garin EH, Olavarria F, Garcia NV, Valenciano B,

Campos A, Young L. Clinical significance of primary vesicoureteral reflux

and urinary antibiotic prophylaxis after acute pyelonephritis: a

multicenter, randomized, controlled study. Pediatrics. 2006;117:626-32.

23. Molitierno JA, Scherz HC, Kirsch AJ. Endoscopic

treatment of vesicoureteral reflux using dextranomer hyaluronic acid

copolymer. J Pediatr Urol. 2008;4:221-8.

24. Lee EK, Gatti JM, Demarco RT, Murphy JP. Long-term

follow up of dextranomer/ hyaluronic acid injection for vesicoureteral

reflux: late failure warrants continued follow up. J Urol.

2009;181:1869-74.

25. Holmdahl G, Brandström P, Läckgren G, Sillén U, Stokland

E, Jodal U, et al. The Swedish reflux trial in children: II.

Vesicoureteral reflux outcome. J Urol. 2010; 184: 280-5.

26. Skoog SJ, Peters CA, Arant BS, Copp HL, Elder JS,

Hudson RG, et al; American Urological Association Education and

Research. Pediatric vesicoureteral reflux guidelines panel summary report:

clinical practice guidelines for screening siblings of children with

vesicoureteral reflux and neonates/infants with prenatal hydronephrosis. J

Urol. 2010;184:1145-51.

|

|

|

|

|