|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2020;57: 959-962 |

|

Identification, Evaluation, and Management of Children With

Autism Spectrum Disorder: American Academy of Pediatrics 2020

Clinical Guidelines

|

Sharmila Banerjee Mukherjee

From Department of Pediatrics, Kalawati Saran Children’s

Hospital, New Delhi, India.

Correspondence to:Dr. Sharmila B. Mukherjee, Department

of Pediatrics, Kalawati Saran Children’s Hospital, New

Delhi. India.

Email:

[email protected]

|

|

The American Academy of

Pediatrics recently published clinical guidelines for

evaluation and management of children and adolescents with

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), nearly 12 years after the

previous version. This article outlines salient features,

highlights significant differences from the 2007 version,

and discusses implications for Indian professionals dealing

with affected families.

Keywords: Dignostic tools,

Investigations, Neuroimaging, Screening.

|

|

T

he American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recently

released clinical guidelines for the evaluation and management of

children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) [1]. The

previous 2007 guidelines covered both separately [2,3]. Many changes

have occurred over the last 12 years: increasing prevalence; revised

nomen-clature and diagnostic criteria of Diagnostic and Statistical

Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5) [4,5]; greater

understanding of clinical profile [6], neurobiology and etiopathogenesis;

advances in genetic testing [7]; evidence-based interventions; and a

paradigm shift to family-centred therapy and holistic management

throughout life. Understandably, there was a strong need for an update.

The increasing worldwide prevalence of ASD means

primary care service providers (PCP) and pediatricians will encounter

ASD routinely. Not only should we be competent enough to recognize,

evaluate and establish diagnosis, we should be empowered to counsel,

help families in decision making, and provide continual support. After

outlining salient features of the 2020 guidelines and highlighting

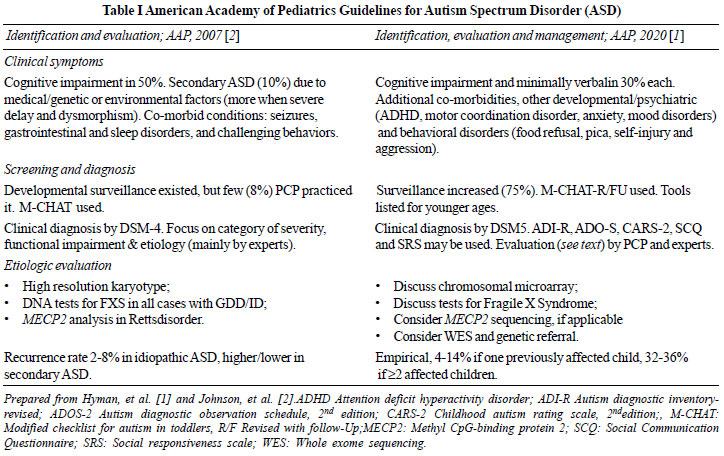

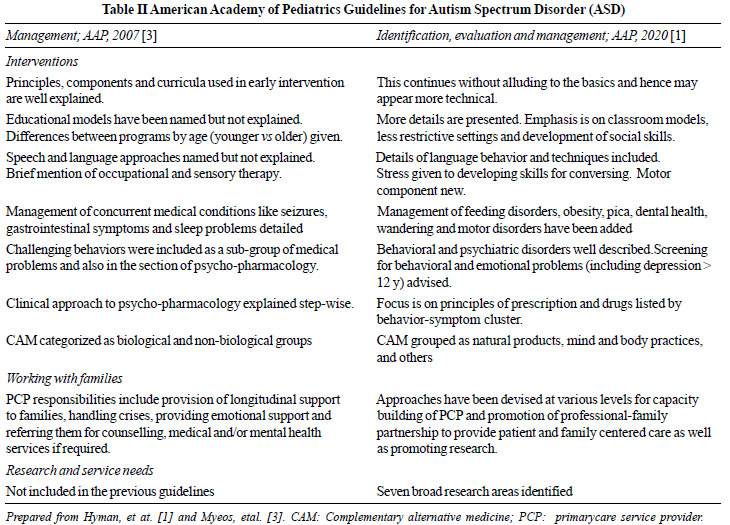

differences from the last one (Tables I and II),

implications for Indian professionals will be discussed.

|

| |

|

| |

Previously, increasing prevalence was attributed to

growing awareness, improving surveillance and less misdiagnoses [2]. The

present status (1in 59) of ASD in the US is also probably due to

broadening of phenotype by DSM-5, universal surveillance and increased

availability of services. Whether biological risk factors contribute to

etiopathogenesis remains uncertain [1]. Earlier diagnosis is more common

in higher socio-economic strata who have better access to services,

while later identification is associated with milder manifestations.

Clinical symptoms include core symptoms and co-existing conditions

(medical, genetic, neuro-developmental, psychiatric and/or behavioral),

the cumulative effect of which influence extent of social and functional

impairment. The guidelines described these in-depth. They also emphasize

the need for holistic evaluation and management to achieve best possible

outcomes.

Screening and Diagnosis

The USA health system practices universal

developmental surveillance with ASD-specific screening at 18 and 24/30

months. Earlier screening is indicated in high-risk individuals or when

red flags for ASD are identified. Suspicion or parental concerns warrant

in-depth evaluation. Establishment of diagnosis is primarily clinical,

based on parental interview, personal observations and DSM-5 criteria.

Though diagnostic tools are not mandatory, they help in extracting

clinical information. Structured evaluation of behaviour, cognition,

language, adaptive function, motor function, hearing, vision and sensory

processing is recommended. Diagnoses established by the aforementioned

compre-hensive assessment in children under 30 months remain stable in

³80% in

adulthood.

Etiologic evaluation comprises of detailed

history-taking and examination (anthropometry, dysmorphism, skin,

neurologic and systemic). The indications for magnetic resonance imaging

(MRI), electroencephalo-graphy (EEG) and metabolic testing remain

individualized, with provision of more details. Genetic evaluation is

recommended in all. The advantages of establishing genetic etiology

include accuracy in counselling, possible specific therapy, avoiding

unnecessary testing, and increased family acceptance.

Interventions

The goals remain minimizing core deficits,

eliminating maladaptive behaviour, and maximizing functional

independence. Intervention should be "individualized, developmentally

appropriate and intensive" [1]. Periodic documentation of performance is

required for monitoring response. The caveat that all interventions

should be evidence-based has been added, with enumeration of

characteristics of effective intervention.

Some sections i.e., models of early

intervention and education, psychopharmacology and complementary

alternative therapy (CAM) are quite technical, since the basics were

extensively explained in the previous guidelines. Hence, non-experts may

not understand them unless they read the earlier version. Management of

medical conditions, social skill instruction, speech and language

therapy, motor therapy (including occupational therapy) and sensory

therapies (the supportive evidence of which is still low) are given in

greater detail.

Evaluation of maladaptive behavior and psychiatric

conditions are separate and described with respect to the atypical

development of ASD. The psychopharmacology section details principles of

prescription and lists medications according to behavior-symptom

cluster. The emerging role of psycho-pharmacogenetic testing is

mentioned. According to the new guidelines, if a family opts for CAM,

safety and effectiveness requires monitoring.

Working with Families

The USA‘Medical home’ model for primary care aims at

"accessible, continuous, comprehensive, family centred, coordinated,

compassionate, and culturally sensitive health care for all children and

youth, including those with special needs" [8]. Though recommended for

ASD since 2007, the process was not well-defined. The latest guidelines

aim at better PCP and caregiver partnership, revolving around shared

decision-making. Resources have been developed for pediatricians to

enable them to deal with emerging issues, counsel effectively, provide

parents with information and direct them towards advocacy and support

groups. It is envisioned that this will result in easier handling of

challenges, smoother transitions during adolescence (higher

education/vocation, sexuality) and adulthood (employment readiness,

medical care, legal guardianship and living arrangements), and better

understanding of ASD related rights and laws.

Research and Service Needs

Key areas identified to direct focus of funding

include, basic and translational science (genetics, epigenetics,

neurobiology, psychopharmacology), clinical trials for focussed

interventions, epidemiological surveillance and implementation research

for health care services.

Implications for the Indian Setting

These guidelines have brought our existing lacunae to

the forefront. Few pediatricians routinely practice developmental

surveillance. Though DSM-5 and indigenous Indian tools are used for

diagnosis, and intervention centres have been established all over the

country, there is wide variability in skills and availability of

multi-disciplinary professionals dealing with ASD, inconsistency in

practice protocols, and minimal quality checking. National Trust

workshops are infrequent and primarily related to disability

certification. Consensus statements and clinical practice guidelines

framed by expert bodies [9,10] sensitize professionals, but do not focus

on capacity-building.

Given these challenges, the provision of easily

accessible, family centred, individualized and intensive,

multi-disciplinary intervention according to these recommendations (but

tailored to Indian settings) to all affected families is still a distant

goal. The need of the hour is planning and implementing evidence-based

concrete strategies that will enable professionals dealing with ASD to

provide global standards of care to these children and their families.

Quality improvement, collaboration and integration is

required among the health, education, social welfare and public health

systems to provide evidence-based, universal care to

children/adolescents and families affected by ASD. The 2020 guidelines

outline strategies for capacity building of PCP to support this

vulnerable population from suspicion of ASD, through diagnosis and

service provision, to adulthood.

REFERENCES

1. Hyman SL, Levy SE, Myers SM. AAP Council on

Children with Disabilities, Section on Developmental and Behavioural

Pediatrics. Identification, Evaluation, and Management of Children with

Autism Spectrum Disorder. Pediatrics. 2020;145:e20193447.

2. Johnson CP, Myers SM, and the Council on Children

with Disabilities. Identification and Evaluation of Children with Autism

Spectrum Disorders. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1183-215.

3. Myers SM, Johnson CP, and the Council on Children

with Disabilities. Management of Children with Autism Spectrum

Disorders. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1162-82.

4. American Psychiatry Association. Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American

Psychiatric Publishers; 2013.

5. Sharma N, Mishra R, Mishra D. The fifth edition of

diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5): What is

new for the pediatrician? Indian Pediatr. 2015;52:141-3.

6. Hodges H, Fealko C, Soares N. Autism spectrum

disorder: Definition, epidemiology, causes, and clinical evaluation.

TranslPediatr. 2020;9(Suppl 1):S55-S65.

7. Schaefer GB, Mendelsohn NJ. Clinical genetics

evaluation in identifying the etiology of autism spectrum disorders:

2013 guideline revisions. Genet Med. 2013:15:399-407.

8. AAP Medical Home Initiatives for Children with

Special Needs Project Advisory Committee. The Medical Home. Pediatrics.

2002;110:184-6.

9. Dalwai S, Ahmed S, Udani V, Mundkur N, Kamath SS,

Nair MKC. Consensus Statement of the Indian Academy of Pediatrics on

Evaluation and Management of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Indian Pediatr.

2017;54:385-93.

10. Subramanyam AA, Mukherjee A, Dave M, Chavda K.

Clinical Practice Guidelines for Autism Spectrum Disorders. Indian J

Psychiatry. 2019;61:254-69.

|

|

|

|

|