V

isiting memory lane back to

the days of an undergraduate medical student, the first visuals

appearing in flash-back of most medical graduate are those of clinical

classes, held during the evening hours, conducted by residents, where

one used to have in-depth discussion on clinical cases and used to

finalize a work-up; where one could elicit sign and symptoms freely and

in a non-threatening environment; where probably one was more

comfortable in admitting mistakes and looking for ways to correct them.

Those sessions by residents and demonstrators helped medical

undergraduates immensely in honing their clinical reasoning and

psychomotor skills.

Residents and demonstrators are involved in routine

teaching activities in most of the departments. It has been estimated

that residents spend approximately 25% of their time teaching medical

students [1]. Another study found that residents spent 19% of their

total time in teaching activities, with 90% of this effort devoted to

teaching associated with patient care and 10% spent in classroom

teaching [2]. Even medical graduates perceive that 18% of the knowledge

they gained during clinical clerkships came from residents and 13% from

interns, compared with 25% from attending physicians and 43% from the

students’ own initiative [3]. As evident, residents have always been

involved in the departmental teaching activities. Of course, all these

figures are from other countries and no such data could be found from

India.

Is the picture same in India? Yes, to a large extent.

Residents are being used in departmental teaching activities without

being formally trained for the same in most of the non-clinical

subjects. We don’t have a data for clinical subjects either, but it

seems that utilization is suboptimal. With the introduction of

competency-based curriculum at undergraduate level there will be

paradigm shift and residents will be increasingly used for formal

teaching activities in India without any formal training. Should we not

have tailor-made faculty development activities for residents, both

senior residents as well as post-graduate students, in order to tap

their full potential in the conduct of the teaching activities in the

department? We are discussing some of these issues here.

RESIDENTS AS TEACHERS

Literature is full of the reasons and means of

involving residents-as-teachers in various medical disciplines, as

explained here.

Regulatory Obligations

The literal meaning of word doctor is – to teach

(derived from Latin verb docere). Being christened with the title

‘doctor’, residents are licensed to teach. Various regulatory bodies

also make it mandatory for residents to teach the undergraduate medical

students as they are given teaching experience certificate for the same,

which is counted for career progression. As per Medical Council of India

(MCI) regulations, three-year experience as Junior Residents and one

year experience as Senior Resident in a recognized medical college in

concerned subject is necessary to be appointed as Assistant Professor

[4]. Naturally residents, who are given teaching experience, must teach

as per regulatory and statutory provisions.

Institutional Requirements

Regulatory bodies have also mandated certain number

of senior and junior residents (tutors in pre- and para-clinical

subjects) to be appointed in medical colleges in all clinical

disciplines. These staffed residents will certainly be utilized for the

teaching purposes of undergraduate students.

Moreover, with the implementation of competency based

medical curriculum in India from the admission session 2019, it has

become imperative to use the services of residents in the teaching – as

more hands are needed for ‘assessment for learning’ purposes [5].

Refining Residents’ Own Competencies

Teaching is the highest form of understanding. As is

often quoted, ‘to teach is to learn twice.’ Being involved in teaching

process in the department provides residents opportunities to improve

their own perceived professio-nal competencies. Over the time, residents

have opined that teaching helps them in being good clinicians – as

teaching stimulates critical thinking and reflection on knowledge,

besides enhancing self-learning [6,7].

In another study, attending doctors expressed the

opinion that students and residents both are benefitted due to teaching

by residents and teaching by residents should be regarded as an integral

part of residency program [8].Thus involving residents in the

departmental teaching activities improve residents’ professional and

clinical competencies, as perceived by them.

BENEFITS OF USING RESIDENTS AS TEACHERS

Students often rate teaching by residents higher than

faculty teaching; and often view residents as more approachable, thus

encouraging them to acknowledge their mistakes easily and accept

feedback readily [9-11]. Residents-as-teachers also provide a kind of

support system for the students by acting as near-peer mentors.

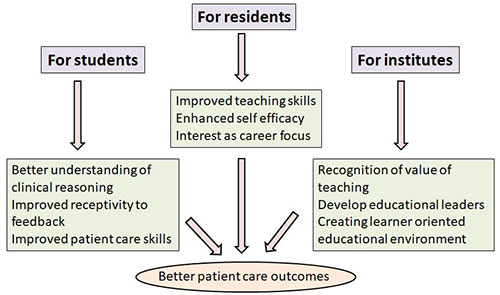

When residents are used as teachers, it is not only

beneficial for the professional development of the students and the

residents but for the overall growth of the institutions also, thus

paving the way for the ultimate improvement in patient care outcomes (Fig.

1).

|

|

Fig. 1 Beneficial effects of using

residents as teacher.

|

NEED AND IMPACT OF EDUCATIONAL TRAINING PROGRAM FOR

RESIDENTS

For generations, residents teach the way they saw

their teachers do that and imbibe skills through ‘role modeling’.

However, learning the art and science of teaching through role modeling

alone is not the correct and optimal way of learning; one needs to have

formal experiential learning through formal training. Only a formally

trained resident in teaching technology will be motivated and dedicated

enough to have overall professional development. There are many reports

of formal residents-as-teachers program from many universities

worldwide. However, considering the unique and contextual nature of

educational content and environment, it may be worthwhile formulating

our own program. Residents and demonstrators are usually involved in

practical demonstrations, bedside teaching and sometimes in assessment

activities like conduct of objective structured clinical/practical

examinations (OSCE/OSPE). They are also increasingly being used for

skill development in the skill labs and other simulated environments.

Medical post-graduates are inherently trained to be

competent in-patient care; they are not trained as ‘medical teachers’.

Unlike requirements of having an educational degree in the field of

humanities and arts, there is no specialized degree in the field of

medicine which they must acquire in order to be medical teachers. This

precise reason has forced regulatory bodies to start faculty development

programs in medical educational techno-logies for the benefit of the

medical faculties. In India, Medical Council of India (MCI) has

developed two such structured programs –Basic Course Workshop in Medical

Educational Technologies and Advance Course in Medical Education [12].

If tailor-made faculty develop-ment programs are required to be

structured for medical faculty, the logic weighs-in on the side of

structuring and implementing such a training program in educational

technologies for residents also.

Literature has evidence that the training improves

the didactic, cognitive and clinical skills of the trainees [13]. Some

qualitative and quantitative studies have provided evidence of utility

of training for residents in educational technologies [6,14,15].

Morrison, et al. by using the Objective Structure Teaching

Examination to determine the impact of a 13-hour teaching training

program for residents found that compared to a control group, residents’

having undergone training had an overall improvement in teaching scores

by 28% [15]. However, Dunnington and DaRosa found minimal changes in

resident teaching behavior by using OSTE, after introducing a

residents-as-teachers intervention [16].

In another study, Snell by using triangulation of

data method tried to evaluate the effectiveness of a training program

for residents-as-teachers, which included five three-hour sessions. She

proved that trained residents had improved resident teaching skills,

showed better application of those skills and maintained those skills

over the academic year [17]. This is perhaps the only kind of study

using data from multi-sources to establish the effectiveness of training

programs for residents in educational technologies.

It is also pertinent to note that many of these

residents would be joining medical colleges as faculty. Others may end

up teaching DNB residents. It would thus be a useful intervention to

change the mindset towards teaching at an early stage of post-graduate

career.

TRAINING PROGRAM - DOCUMENTED EFFORTS

Training modules for the formal training of residents

in educational technologies and principles have been developed and

implemented by various universities and colleges, ranging from 2 hour

modules to workshops for 2-3 days to weekly / fortnightly one hour

training for up to six months duration [15,16]. Longitudinal training

programs in the form of electives for residents have also been designed,

implemented and evaluated [18-20]. In most of these training programs

and workshops, the most commonly used instruction methods were -

lectures, small group interactive sessions and role-play. Large group

interactive discussions and standardized students were the least

commonly used methods [21].

A literature search could retrieve very few studies

having used the concept of resident-as-teachers in India [22-24].Of

these studies, only Senior Resident Training on Educational Principles

(STEP) study has described a structured training module in the form of

workshop delivered to senior residents for enhancing their teaching

skills [22]. Maharashtra University of Health Sciences also started

‘resident as teacher’ program.[25] All such programs started at various

institutes could not sustain for various reasons; one of them possibly

being lack of conviction about utility of such an exercise. As

literature shows content, structure, duration and delivery variability

of different workshops/training programs designed for

residents-as-teachers, with hardly any visibility of such training

modules and programs in India and as the use of residents-as-teachers is

in transient phase in congruence with the paradigm shifts in the medical

education and undergraduate and post-graduate medical curriculum in

India. It is imperative that a structured training program in medical

education technologies for residents’ training in India be designed.

PROPOSED TRAINING MODULE

Though the need and effectiveness of a structured

program in educational technologies for residents is self-explanatory,

less than 10% of residents and interns reported to have undergone any

sort of training in teaching. This fact alone emphasizes the need to

design and implement a structured program for residents-as-teachers,

particularly tailor-made for our needs and requirements. Due to

differences in teaching-job profile, the structured module used for

training of the medical faculty can’t be used for the residents also.

Accordingly, a ‘Training-module for Residents’ in

India in Medical education technologies (TRIM)’ in the form of workshop,

based on some fundamental assumptions has been proposed here (Box

1).

|

Box 1 Fundamental Assumptions for Designing

Training Module for Residents

• Residents will be involved in teaching of

cognitive, psychomotor and affective domains to undergraduates

(UGs) including professionalism and ethics.

• Residents will be mainly involved in

interactive small group teaching and bedside teaching.

• Residents will act as role models for UGs,

thereby affecting soft skills including professionalism, ethics,

communication of UGs.

• Residents will act as mentors for UGs.

• Residents will be used for assessment of

UGs, of all domains, including assessment of knowledge.

• Residents will be particularly used for

assessment in simulated conditions, and more for formative

purposes.

• Residents will not be used for curriculum design or

curriculum evaluation.

|

The goal of the proposed program is to orient the

residents to the use of medical education teaching and assessment tools.

The content of the proposed program has been designed by extracting data

from three sources – previous experience of institutes in designing and

implementing such programs; MCI requirements for residents in India; and

curricular mandates requiring use of residents in students’ teaching as

per authors own experiences. Three main areas identified for training

and orientation of residents are – teaching principles and tools,

assessment and assessment tools, mentoring and teamwork.

The training module has been structured with the

objectives of sensitizing and training residents in the concepts of –

group dynamics and team-based learning, small group teaching, bedside

teaching, simulation based teaching and assessment, assessment of

learning and assessment for learning, and mentoring. These focused areas

align well with the teaching job profile of the residents. However,

efforts must be made to sustain this training through reinforcements

during residency as well as during working period as faculty, as and

when a resident joins as faculty in any institute. The description of

the sessions and the instructional strategies proposed for delivery of

those sessions has been briefed in Web Table I.

This workshop of 22 hours can be conducted over three

days, with 30-35 residents. If three-day continuous workshop is not

possible, the institute concerned can distribute sessions daily, as

appropriate.Trained faculty members from all departments can be

involved. A self-explanatory and most-appropriate instructional method

for the conduct of each session has been recommended; however local

factors like available infrastructure, availability of time, expertise

of facilitators will ultimately decide the choice of any of these

methods.

Local planners may consider adding sessions on –

appropriate use of multimedia, integrated teaching, assessment in

integrated teaching-learning, self-directed learning – if their local

needs direct the same. Similarly, based upon expertise of the faculty

other instructional strategies like – cine-meducation, team-based

learning, team objective structured clinical examination – can be used

[27-29]. One can also explore the possibility of using online platforms

and educational strategies for the delivery of the content; even

partially, if not fully. Combination of synchronous and face-to-face

training followed by asynchronous or synchronous online training can be

a viable option in institutes with heavy patient footfall, making time

constraints for residents a real issue.

EXPECTED OUTCOMES

What is expected to be achieved with this module? It

is not expected that with this training module the residents will be

fully equipped with all the teaching and assessment tools available in

the armamentarium. Only expectation is that the sensitized residents

after the training will start applying these concepts in their teaching

activities. They are expected to be handy resources as facilitators in

the conduct of Objective structured clinical examination/Objective

structured practical examination (OSCE/OSPE) in the department. After

the training, they must be field-ready to act as instructors in the

upcoming skill labs.

It is further expected that residents teaching skills

will evolve and will improve from ‘being novice’ to at least ‘advance

beginners’. More importantly residents are expected to build the concept

of ‘transfer of training’ at their young age as teachers and understand

the utility of having a learner-oriented educational environment in the

institute.

PROGRAM EVALUATION

A detailed plan of action for program evaluation of

the proposed "Training-module for Residents’ in India in Medical

education technologies (TRIM)" is out of the scope of this paper.

However, we are trying to issue generalized suggestions, so that the

program is evaluated and monitored continuously for refinement as well

as for ensuring accountability. The evaluation must include both process

evaluation and outcome evaluation. While outcome evaluation will measure

if the desired change has been achieved or not, the process evaluation

will measure how the desired change was achieved – that is if the

program was carried out as planned. Typically, a combination of logic

and Kirkpatrick’s model will be good enough for such a program

evaluation.

CHALLENGES IN IMPLEMENTING TRAINING PROGRAM

First challenge will be to find trained faculty for

the conduct of the training program of the residents as teacher. The

faculty needs to be trained themselves. The Medical Council of India’s

new guidelines, making revised basic course workshop as mandatory

requirement for promotion of faculty will result in many trained faculty

members. Faculty inertia and resistance will be the next big challenge

in the implementation of teachers training program for residents. The

resistance is not baseless even. Faculty in medical colleges is already

involved in multitasking – patient care, teaching postgraduates and

undergraduates, curriculum development, administrative duties to name a

few. Making arrangements and then conducting a workshop for residents

will be labor intensive; though the very incentive that the trained

residents will ultimately prove helping hands for these faculty members

for undergraduate teaching will motivate faculty to plan and conduct

such teachers training programs for residents.

Residents have multiple tasks to do – patient care,

research, participation in continued medical education programs

including training in research methodologies; so tapping their full

potential as teachers is a challenge in itself. Consequently, many

residents might be reluctant to attend teachers training

program.However, owing to the huge personal and professional benefits of

teaching undergraduate students, residents will get enough sensitization

to attend such a training program.

The training program needs to be monitored also, at

all levels, not only for continuous refinement and support but also for

seamless implementation. Monitoring any program is a challenge in

itself. Program evaluation and monitoring demands trained manpower,

infrastructure, time and coordination among different stakeholders.

Program evaluation plan, as proposed above, will be required to be

designed, once such a program is adopted for implementation.

CONCLUSIONS

There is huge man-power and potential available with

us in medical institute in India in the form of junior and senior

residents. Though routinely used in patient care, they must be used as

facilitators and instructors for departmental teaching and assessment

activities. It is logical to assume that orientation and training of

residents in the form of a workshop module will improve their acumen for

teaching activities. An informed, sensitized, oriented and trained

resident will prove to be a useful and productive resource for any

institute.

Contributors: TS: conceptualized the paper; RM:

prepared the initial manuscript:PG: finalized it; All authors provided

critical inputs and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: None; Competing interests: None

stated.

REFERENCES

1. Jarvis-Selinger S, Halwani Y, Joughin K, Pratt D,

Scott T, Snell L. Supporting the development of residents as teachers:

Current practices and emerging trends. Members of the FMEC PG

consortium; 2011.

2. Sheets KJ, Hankin FM, Schwenk TL. Preparing

surgery house officers for their teaching role. American Journal of

Surgery 1991;161;443-49.

3. Barrow MV. Medical student opinions of the house

officer as a medical educator. J Med Educ.1966; 41:807-10.

4. Medical Council of India. Minimum Qualification of

Teachers in Medical Institutions Regulations, 1998. Available from:https://www.mciindia.org/documents/rules

AndRegulations/Teachers-Eligibility-Qualifications-Rgulations-1998.pdf.

Accessed January 10, 2020.

5. Singh T, Anshu, Modi JN. The Quarter Model: A

Proposed Approach for In-training Assessment of Undergraduate Students

in Indian Medical Schools. Indian Pediatr. 2012; 49:871-76.

6. Busari JO, Prince KA, Scherpbier AJ, Van der

Vleuten CP, Essed GG. How residents perceive their teaching role in the

clinical setting – a qualitative study. Medical Teacher 2002; 24:57-61.

7. Sheets KJ, Hankin FM, Schwenk TL. Preparing

surgery house officers for their teaching role. Am JSurg1991;

161:443-49.

8. Busari JO, Scherpbier AJ, Van der Vleuten CP,

Essed GG. The perception of attending doctors of the role of residents

as teachers of undergraduate clinical students. Med Educ. 2003;

37:241-47.

9. Whittaker LD Jr, Estes NC, Ash J, Meyer LE. The

value of residentteaching to improve student perceptions of surgery

clerkships andsurgical career choices. Am J Surg.2006; 191:320-24.

10. Tolsgaard MG, Gustafsson A, Rasmussen MB, Hoiby

P, Muller CG,Ringsted C. Student teachers can be as good as associate

professorsin teaching clinical skills. Med Teach 2007; 29:553-57.

11. Ross MT, Cameron HS.Peer assisted learning: a

planning andimplementation framework: AMEE Guide no. 30. Med Teach.2007;

29:527-45.

12. Medical Council of India. Decisions of the

council regarding faculty development programmes. Available from:

https://mciindia.org/CMS/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/3_MCI_

decisions_on_MET.pdf. Accessed February 03, 2020.

13. Irby DM. What Clinical Teachers in Medicine Need

to Know?Acad Med. 1994:610:333-42.

14. Khera N, Stroobant J, Primhak RA, Gupta R, Davies

H. Training the ideal hospitaldoctor: The specialist registrars’

perspective. Medical Education 2001; 35:957-66.

15. Morrison EH, Rucker L, Boker JR, Hollingshead J,

Hitchcock MA, Prislin MD, et al. A pilot randomized,controlled

trial of a longitudinal residents-as-teachers curriculum. Acad

Med.2003;78:722-29.

16. Dunnington GL, DaRosa D. A prospective randomized

trial of a residents-as-teachers training program.Acad Med.1998;

73:696-700.

17. Snell L. Improving medical residents’ teaching

skills. Ann R Coll of PhysSurg Can.1989; 22:125-28.

18. Bharel M, Jain S. A longitudinal curriculum to

improve resident teachingskills. Med Teach. 2005; 27:564-66.

19. Mann KV, Sutton E, Frank B. Twelve tips for

preparing residents as teachers. Med Teach. 2007;29:301-06.

20. Weissman MA, Bensinger L, Koestler JL. Resident

as teacher: educatingthe educators. Mt Sinai J Med. 2006; 73:1165-69.

21. Morrison EH, Friedland JA, Boker J, Rucker L,

Hollingshead J, Murata P.Residents-as-teachers training in U.S.

residency programs and offices ofgraduate medical education. Acad Med.

2001;76: S1-S4.

22. Singh S. Senior resident training on educational

principles (STEP): A proposed innovative step from a developing nation.

J EducEval Health Prof.2010;7:3 (online). Available from:

https://www.jeehp.org/DOIx.php?number=45. Accessed February 03,

2020.

23. Kumar A, Agarwal D. Resident-to-resident bedside

teaching: An innovative concept. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2019; 67:1901-02.

24. Ghosh SK. Resident doctors: Keystone of anatomy

teaching. Clin Teach.2014; 11:461-62.

25. Homeo Book [Page on internet]. MUHS Master of

Science (Health Professions Education) 2016 admission. Available from:

https://www.homeobook.com/muhs-master-of-science-health-professions-education-2016-admission/.

Accessed May 04, 2020.

26. Wilkinson M. Team building activity – Crossing

the river. Available from:

https://www.leadstrat.com/leadership-strategy-resources/team-building-activity-crossing-the-river/.

Accessed February 04, 2020.

27. Kadeangadi DM, Mudigunda SS. Cinemeducation:

Using films to teach medical students. J SciSoc.2019;46:73-74.

28. Chhabra N, Kukreja S, Chhabra S, Khodabux S,

Sabane H. Team based learning strategy in biochemistry: Perceptions and

attitudes of faculty and 1st year medical students. Int J Appl Basic Med

Res. 2017;7:72-7.

29. Amini M, Moghadami M, Kojuri J, Abbasi H, Abadi

AA, Molaee NA, et al. Using TOSCE (Team Objective Structured

Clinical Examination) in the second national medical sciences Olympiad

in Iran. J Res Med Sci. 2012; 17:975-8.