|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2020;57: 929-935 |

|

Hyperinflammatory Syndrome in Children

Associated With COVID-19: Need for Awareness

|

|

Chandrika S Bhat, 1

Latika Gupta,2 S

Balasubramanian,3

Surjit Singh4 and

Athimalaipet V Ramanan5

From 1Pediatric Rheumatology Service,

Rainbow Children’s Hospital, Bangalore, Karnataka, India; 2Department

of Clinical Immunology and Rheumatology, Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate

Institute of Medical Sciences, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh India; 3Department

of Pediatrics, Kanchi Kamakoti CHILDS Trust Hospital, Chennai, Tamil

Nadu, India; 4Allergy Immunology Unit, Department of

Pediatrics, Advanced Pediatrics Centre, Post Graduate Institute of

Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India; and 5Bristol

Royal Hospital for Children and Translational Health Sciences,

University of Bristol, Bristol, UK.

Correspondence: Dr Chandrika S Bhat, Rainbow

Children’s Hospital, Marathahalli, Bengaluru 560 037, Karnataka, India.

Published online: July 15, 2020;

PII: S097475591600208

|

|

The pandemic of COVID-19

initially appeared to cause only a mild illness in children.

However, it is now apparent that a small percentage of children

can develop a hyperinflammatory syndrome labeled as Pediatric

inflammatory multisystem syndrome - temporally associated with

SARS-CoV-2 (PIMS-TS). Features of this newly recognized

condition may include persistent fever, evidence of

inflammation, and single or multi-organ dysfunction in the

absence of other known infections. Some of these children may

share features of Kawasaki disease, toxic shock syndrome or

cytokine storm syndrome. They can deteriorate rapidly and may

need intensive care support as well. The PCR test is more often

negative; although, most of the children have antibodies to

SARS-CoV-2. Although the pathogenesis is not clearly known,

immune-mediated injury has been implicated. We herein provide

current information on this condition, in order to raise

awareness amongst pediatricians.

Keywords: Kawasaki disease, Macrophage

activation syndrome, Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in

children and adolescents temporally related to COVID-19,

Pediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome - temporally

associated with SARS-CoV-2 (PIMS-TS).

|

|

C

hildren younger than 18 years have been reported

to constitute only a small proportion of cases of coronavirus disease

(COVID-19). Whilst initial reports described an asympto-matic or milder

illness in children [1,2], several countries have now noticed a new

hyper-inflammatory syndrome affecting a small percentage of children

[3]. This condition appears to share features with pediatric

inflammatory diseases such as Kawasaki disease (KD) and Toxic shock

syndrome (TSS) [4].

The first case of classic KD with concurrent COVID-19

in a child was reported from United States [5]. Subsequently, health

authorities in the United Kingdom (UK) issued an alert describing a

serious illness requiring intensive care in children. A number of other

regions significantly affected by COVID-19 such as New York, Italy and

France also reported increasing numbers of children with a similar

inflammatory syndrome [3]; the first such case was reported from India

only recently [6]. The Royal College of Pediatrics and Child Health

(RCPCH) published a guidance to raise awareness amongst clinicians for

this newly recognized condition called Pediatric inflammatory

multisystem syndrome - temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2 (PIMS-TS)

[4]. A similar clinical entity was defined as the Multisystem

inflammatory syndrome in children and adolescents temporally related to

COVID-19 by the World Health Organization (WHO) [7] and Multisystem

inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) associated with COVID-19 [8]

by Centers for Disease Control and prevention (CDC) (Box I).

Although little is known about the epidemiology, cases of PIMS-TS seem

to appear few weeks after the COVID-19 peak in the population. As of 13

May, 2020, there were more than 300 cases of suspected PIMS-TS in Europe

and North America [3]. With India lagging behind the peak curve, the

authors hypothesize that we may also see a spurt in this illness in the

coming days.

| |

|

Box I Proposed Case Definitions for the

Hyperinflammatory Syndrome Associated With COVID-19 [4,7,8]

World Health Organization

Children and adolescents 0-19 years of age

with fever >3 days AND two of the following:

(a) Rash or bilateral non-purulent

conjunctivitis or muco-cutaneous inflammation signs (oral, hands

or feet)

(b) Hypotension or shock

(c) Features of myocardial

dysfunction, pericarditis, valvulitis, or coronary abnormalities

(including ECHO findings or elevated Troponin/NT proBNP)

(d) Evidence of coagulopathy (by PT,

PTT, elevated D-dimer)

(e) Acute gastrointestinal problems (diarrhea,

vomiting, or abdominal pain)

AND

Elevated markers of inflammation such as ESR,

CRP or procalcitonin.

AND

No other obvious microbial cause of

inflammation, including bacterial sepsis, staphylococcal or

streptococcal shock syndromes.

AND

Evidence of COVID-19 (RT-PCR, antigen test or

serology positive), or likely contact with patients with

COVID-19.

Royal College of Pediatrics and Child Health

A child presenting with persistent fever,

inflammation (neutrophilia, elevated CRP and lymphopenia) and

evidence of single or multi-organ dysfunction.

This may include children fulfilling full or

partial criteria for Kawasaki disease.

Exclusion of any other microbial cause,

including bacterial sepsis, staphylococcal or streptococcal

shock syndromes, infections associated with myocarditis such as

enterovirus.

SARS-CoV-2 PCR testing may be positive or

negative.

Centers for Disease Control

An individual aged <21 years presenting with

fever, laboratory evidence of inflammation and evidence of

clinically severe illness requiring hospitalization, with

multisystem ( ³2)

organ involvement (cardiac, renal, respiratory, hematologic,

gastrointestinal, dermatologic or neurological)

(i) Fever ³38.0°C

for ³24

hours, or report of subjective fever lasting

³24

hours.

(ii) Laboratory evidence (but not

limited to) of one or more of the following: an elevated CRP,

ESR, fibrinogen, procalcitonin, D-dimer, ferritin, LDH, or

interleukin 6, elevated neutrophils, reduced lymphocytes and low

albumin.

AND

No alternative plausible diagnoses

AND

Positive for current or recent SARS-CoV-2

infection by RT-PCR, serology, or antigen test; Or COVID-19

exposure within 4 weeks prior to the onset of symptoms.

CRP: C-reactive protein; ESR: Erythrocyte sedimentation rate;

LDH: Lactate dehydrogenase.

|

CLINICAL FEATURES

One of the initial reports [9] described a cluster of

eight children with hyperinflammatory shock. Mean age at presentation

was 8.8 years with a predilection for boys of Afro-Caribbean descent and

seven of these were above the 75 th

centile for weight. Mean duration of fever at presentation was 4.3 days.

Mucocutaneous changes (rash, conjunctivitis, peripheral edema) with

significant gastro-intestinal symptoms were noted in all of them. All 8

patients developed severe refractory shock with a mean ferritin level of

1086.6 ng/mL. One child required extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation

(ECMO) for refractory shock but eventually died after 6 days of

hospitalization. None of the children had respiratory symptoms and only

two tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 PCR, while all of them tested

positive for the antibody [9]. Ten children presenting with features of

classic or incomplete KD were reported from Italy [10] with mean age and

duration of fever of 7.5 years and 6 days, respectively. Apart from

gastrointestinal and mucocutaneous symptoms, menin-geal signs were also

reported in this subset. Half of them developed KD shock syndrome (KDSS)

with peak ferritin levels of 1176 ng/mL. In comparison to children with

KD in pre-pandemic times the current phenotype included older children

with more severe disease, significant cardiac involvement and macrophage

acti-vation syndrome (MAS) [10]. Again, only two tested positive for

SARS-CoV-2 PCR, but eight tested positive for the antibody. In both the

groups, inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein, procalcitonin,

ferritin, triglycerides, and D-dimer) were significantly elevated. An

abnormal echocardiogram with myocardial dysfunc-tion and coronary artery

abnormalities were observed in 60% children, and two also had coronary

aneurysms [10].

More recently, a French study [11] described a new

syndrome complex of acute heart failure and hyper-inflammation in

children. Initial presentation predomi-nantly included fever (100%) and

gastro-intestinal symptoms (80%) such as abdominal pain, vomiting and

diarrhea. Although mucocutaneous changes suggestive of KD were noted,

none of them met the criteria for classic KD. Echocardiography was

significant for left ventri-cular dysfunction with a low ejection

fraction. Inflam-matory markers (CRP, D-dimer) were raised in all.

Coronary artery dilatation was seen in 17%, but as opposed to classic

KD, none of them developed coronary aneurysms. Complete recovery was

seen in 71% of children, suggesting that myocardial edema rather than

necrosis was likely responsible for heart failure. This is in contrast

to the adult population, where myocardial necrosis has been incriminated

in the pathogenesis [11].

The importance of suspecting PIMS-TS in febrile

adolescent children with gastrointestinal symptoms during this pandemic

cannot be overemphasized. This unusual presentation was also reinforced

in a case series of eight children from UK, initially suspected to have

appendicitis [12]. Although they had very high CRP levels, abdominal

imaging demonstrated non-specific features (e.g. lymphadenopathy

or ileitis) rather than appendicitis. Subsequently, half of these

children required intensive care admission for hemodynamic instability.

Apart from peripheral or periorbital edema, none of them had features to

suggest classic KD and five tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 [12].

In a larger case series of 58 children (median age 9

years) from UK [13], all presented with fever and combi-nations of

abdominal pain (53%), diarrhea (52%) or rash (52%). Three clinical

patterns were identified in this cohort- fever with raised inflammatory

markers (39.6%) without features of KD, TSS or organ failure; shock

(50%) with evidence of left ventricular dysfunction (62%); and those

fulfilling criteria for KD. Coronary artery aneurysms were noted across

all three groups (8/58). Compared to other inflammatory disorders, those

with PIMS-TS were older and had lower hemoglobin levels and lymphocyte

counts, and higher white blood cell count, neutrophil count and CRP

levels (Table I) [13].

Table I Comparison of PIMS-TS With Classic KD, KDSS and TSS [13]

|

Features |

PIMS-TS (n=58) |

KD (n=1132) |

KDSS (n=45) |

TSS (n=46) |

|

Age at onset, y |

9.0 (5.7-14) |

2.7 (1.4-4.7) |

3.8 (0.2-18) |

7.38 (2.4-15.4) |

|

CRP, mg/L |

229 (156-338) |

67 (40-150) |

193 (83-237) |

201 (122-317) |

|

Hemoglobin, g/L |

92 (83-103) |

111 (105-119) |

107 (98-115) |

114 (98-130) |

|

Lymphocytes, ×109/L |

0.8 (0.5-1.5) |

2.8 (1.5-4.4) |

1.6 (1-2.5) |

0.63 (0.41-1.13) |

|

Ferritin, µg/L

|

610 (359-1280) |

200 (143-243) |

301 (228-337) |

– |

|

NT-Pro-BNP, pg/mL |

788 (174-10548) |

41 (12-102) |

396 (57-1520) |

– |

|

Troponin, ng/L |

45 (8-294) |

10 (10-20) |

10 (10-30) |

– |

|

D-dimer, ng/mL |

3578 (2085-8235) |

1650 (970-2660) |

2580 (1460-2990) |

|

|

Data are median (IQR); PIMS-TS: pediatric inflammatory

multisystem syndrome-temporally related to SARS-CoV-2, KD:

Kawasaki disease, KDSS: Kawasaki disease shock syndrome, TSS:

Toxic shock syndrome, CRP: C-reactive protein. |

It appears that these children may develop single or

multi-organ dysfunction with persistent fever and features of

inflammation (neutrophilia, elevated CRP and lymphopenia). This may

progress on to shock. In patients who turn out to be SARS-CoV-2 PCR

negative, other microbial causes need to be actively considered and

excluded [4]. In addition to KD and TSS, secondary hemophagocytic

lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) in associa-tion with common tropical

infections should also be considered in similar clinical settings. Based

on available data, we speculate that there could be three distinct

phenotypes of hyperinflammation in children (Table II).

PATHOGENESIS

Approximately two-thirds of patients with PIMS-TS are

COVID-19 PCR negative, a proportion of these being serologically

positive, suggesting an immune-mediated pathogenesis over a direct virus

invasion-mediated tissue injury. Infection with COVID-19 triggers the

formation of antibodies to viral surface epitopes. Virus neutrali-zation

is a direct function of the stochiometric concen-tration and affinity of

the antibodies. It is believed that low titer non-neutralizing

antibodies may accentuate virus triggered immune responses instead,

thereby increasing the risk of severe illness in affected individuals

[14]. While blocking antibodies against the angiotensin converting

enzyme (ACE) receptor binding regions (such as the RBD and HR2 region of

S protein) are deemed protective, those directed against nucleocapsid

and other epitopes on S protein are not [15,16]. Weak antibody coated

virus gets internalized by Fc receptors, followed by endosomal release

of the virion and subsequent Toll-like receptor and cytosolic RNA sensor

triggered IFN a

responses. These antibody dependent enhancement (ADE) responses have

been implicated in COVID-19 induced immune injury. Although evidence

base for this pathway is demonstrated for coronaviruses [16], the exact

role in PIMS-TS is only speculative [17].

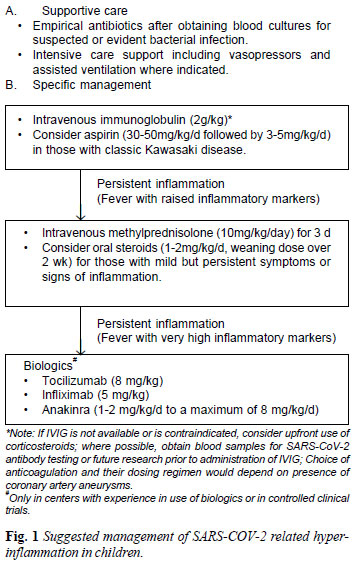

MANAGEMENT

Conventionally, treatment of KD involves use of

intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and high dose aspirin as first line

agents [18]. The use of IVIG for PIMS-TS may help in facilitating

neutralization of virus and associated superantigens and downregulation

of the inflammatory cytokines [19,20]. IVIG (2 g/kg) has been used in

most published series on PIMS-TS as first line therapy. The effects;

however, may be short-lived [9,10]. In those with features of classic

KD, it would be appropriate to consider use of aspirin (30-50 mg/kg/day

followed by 3-5 mg/kg/day) along with IVIG [18]. The role of aspirin in

children with hyperinflammation without features of KD is not known, and

we believe that it has a limited role in these children. Although the

role of anticoagulation is not clearly defined, it should be considered

on a case-by-case basis in children with hyperinflammatory syndrome. The

choice of anti-coagulation and their dosing regimen would also depend on

the presence of coronary aneurysms.

In select cases, especially those who do not respond

to IVIG, adjunctive immunomodulatory therapy may be necessary to control

inflammation. It is known that use of corticosteroids in KD is

associated with earlier resolution of fever and lower incidence of

coronary artery abnormalities [18,21]. Corticosteroids are also used as

first line therapy in children with MAS. On this basis, it is plausible

that these agents may be effective in PIMS-TS, especially in those with

features of cytokine release syndrome (CRS). Recently published case

series have shown that corticosteroids (initially pulse intravenous

methylprednisolone 10 mg/kg/day for 3 days followed by oral prednisolone

in a gradual tapering regimen) are useful adjuncts to IVIG in patients

with PIMS-TS [9,10,21].

Whilst not much is known about the pathogenesis of

PIMS-TS, it is clear that there is elevation of cytokines such as IL-1,

IL-6, IL-18 and IFN- a

in most children who develop MAS [22]. Although this does not

necessarily establish causality, specific cytokine blockade has resulted

in remission of MAS on many occasions [23]. Also, specific blockade of

TNF-a with

infliximab has been tried in children with KD resistant to IVIG [18].

Along with IL-6, several other cytokine blockade therapies are currently

under evaluation in adults with COVID-19. As we understand more about

targeted therapy in adults with COVID induced CRS, we might consider

trials of these agents in PIMS-TS [24,25]. Extrapolating these

data, it is possible that there may be a role for specific cytokine

blockade in PIMS-TS as well. Apart from one case report describing the

use of tocilizumab in a child with KD and SARS-CoV-2 [6], data on use of

biologics for this indication are still lacking. Until such data are

available, it would be reasonable to consider these therapies only under

special circumstances (in children with high CRP levels and those

refractory to IVIG/corticosteroids) either in controlled clinical trials

or by clinicians experienced in use of biologics. Where considered

appropriate, therapy with biologics such as tocilizumab (8 mg/kg) or

infliximab (5 mg/kg) should be considered. Based on existing evidence,

suggested management of children with SARS-CoV-2 related

hyperinflammation has been summarized in figure 1.

|

Apart from immunomodulation, supportive care plays a

key role in the management of these children. Deterioration can be

rapid, and it is important for clinic-ians to monitor for signs of

worsening inflammation [4].

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The important answers lie in understanding the immune

origins of this condition. There is a need for clinical trials using

adaptive designs (Bayesian methodology) which would enable us to

evaluate therapies including IL-6, IL-1 and anti-TNF blockade in

children with this syndrome.

Despite the emerging literature, there are still a

lot of unknowns regarding SARS-CoV-2. It is important to gather data on

the condition to understand the damage caused and risk for recurrence as

well as long term implications including the risk for autoimmune disease

later in life. Real time surveillance studies such as the WHO clinical

data platform (https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/332236) and

the British Pediatric Surveil-lance Unit (BPSU) study (https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/work-we-do/bpsu/study-multisystem-inflammatory-

syndrome-kawasaki-disease-toxic-shock-syndrome) can gather

information to help further our understanding of this disease. There is

now an overwhelming need for registries for data collection and

integration, especially in India [26,27]. Going forward, multicenter and

perhaps multi-national collaborative studies may be required to fill

existing gaps in our knowledge of the current pandemic and the new

syndrome in children.

In the Indian context, we perceive a definite need

for increased awareness of this unique clinical syndrome amongst parents

and pediatricians alike in the midst of multitude of several common

infections such as dengue, when a child presents with fever with

variable accompanying symptoms and signs and raised inflammatory

markers.

Contributors: CB, LG, AVR: substantial

contribution to the conception and design of the work, preparation and

finalization of the draft; CB, LG, SB, SS, AVR: substantial

contributions to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data

for the work; SB, SS, AVR: Critical Revision for important intellectual

content; CB, LG, SB, SS, AVR: final approval of the version to be

published, and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work

in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any

part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: None; Competing interests: None

stated.

REFERENCES

1. Balasubramanian S, Rao NM, Goenka A, Roderick M,

Ramanan AV. Coronavirus disease [COVID-19] in children - What we know so

far and what we do not. Indian Pediatr. 2020; 57(5):435-442.

2. Meena J, Yadav J, Saini L, Yadav A, Kumar J.

Clinical features and outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Indian Pediatr.

2020;S097475591600203. [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 24].

3. European Centre for Disease Prevention and

Control. Pediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome and SARS-CoV-2

infection in children – 15 May, 2020. ECDC: Stockholm; 2020.

4. Royal College of Pediatrics and Child Health.

Guidance–Pediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome temporally

associated with COVID-19, 2020. Available from:

https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/resources/guidance-pediatric-multi

system-inflammatory-syndrome-temporally-associated-covid-19.

Accessed May 5, 2020.

5. Jones VG, Mills M, Suarez D, Hogan CA, Yeh D,

Bradley SJ, et al. COVID-19 and Kawasaki disease: novel virus and

novel case. Hosp Pediatr. 2020 Jun; 10(6): 537-540. [E-pub ahead of

print].

6. Balasubramanian S, Nagendran TM, Ramachandran B,

Ramanan AV. Hyper-inflammatory syndrome in a child with COVID-19 treated

successfully with intravenous immunoglobulin and tocilizumab. Indian

Pediatr. 2020; S097475591600180. [E-pub ahead of print].

7. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and

adolescents with COVID-19. 15 May 2020 Scientific brief: World Health

Organisation. Available from: https://www.

who.int/publications-detail/multisystem-inflammatory-syndrome-in-children-and-adolescents-with-covid-19.

Accessed May 31, 2020.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Emergency preparedness and response: Health alert network. Published May

14, 2020. Available from: https://emergency.cdc.gov/han/

2020/han00432.asp. Accessed May 22, 2020.

9. Riphagen S, Gomez X, Gonzalez-Martinez C,

Wilkinson N, Theocharis P. Hyperinflammatory shock in children during

COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020 May 23; 395 (10237):1607-1608.

10. Verdoni L, Mazza A, Gervasoni A, Martelli L,

Ruggeri M, Ciuffeda M, et al. An outbreak of severe Kawasaki-like

disease at the Italian epicentre of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic: An

observational cohort study. Lancet. 2020; 395: 1771-78.

11. Belhadjer Z, Méot M, Bajolle F, Khraiche D,

Legendre A, Abakka S, et al. Acute heart failure in multisystem

inflammatory syndrome in children [MIS-C] in the context of global

SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Circulation. 2020 May 17;

CIRCULATIONAHA.120.048360. [E-pub ahead for print].

12. Tullie L, Ford K, Bisharat M, Watson T, Thakkar

H, Mullassery D, et al. Gastrointestinal features in children

with COVID-19: an observation of varied presentation in eight children.

Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4: e19-e20.

13. Whittaker E, Bamford A, Kenny J, et al.

Clinical characteristics of 58 children with a pediatric inflammatory

multisystem syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2. JAMA. 2020;

e2010369. [E-pub ahead for print].

14. Yu H, Sun B, Fang Z, Zhao J, Liu X, Li Y, et

al. Distinct features of SARS-CoV-2-specific IgA response in

COVID-19 patients. European Resp J. 2020; 2001526. [E-pub ahead for

print].

15. Iwasaki A, Yang Y. The potential danger of

suboptimal antibody responses in COVID-19. Nature Reviews Immunology.

2020. Available from: http://www.nature.

com/articles/s41577-020-0321-6. Accessed May 29, 2020.

16. Wang Q, Zhang L, Kuwahara K, Li L, Liu Z, Li T,

et al. Immunodominant SARS coronavirus epitopes in humans

elicited both enhancing and neutralizing effects on infection in

non-human primates. ACS Infect Dis. 2016; 2(5):361-376.

17. Shen L, Fanger MW. Secretory IgA antibodies

synergize with IgG in promoting ADCC by human polymor-phonuclear cells,

monocytes, and lymphocytes. Cellular Immunology. 1981; 59(1):75-81.

18. McCrindle BW, Rowley AH, Newburger JW, Burns JC,

Bolger AF, Gewitz M, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term

management of Kawasaki disease: A scientific statement for health

professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation.

2017;135: e927-e99.

19. Burns JC, Franco A. The immunomodulatory effects

of intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in Kawasaki disease. Expert Rev

Clin Immunol. 2015;11:819-25.

20. Lo MS, Newburger JW. Role of intravenous

immunoglobulin in the treatment of Kawasaki disease. Int J Rheum Dis.

2018;21:64-9.

21. Kobayashi T, Saji T, Otani T, Takeuchi K,

Nakamura T, Arakawa H, et al. Efficacy of immunoglobulin plus

prednisolone for prevention of coronary artery abnormalities in severe

Kawasaki disease [RAISE study]: A randomised, open-label,

blinded-endpoints trial. Lancet. 2012; 379:1613-20.

22. Schulert GS, Grom AA. Pathogenesis of macrophage

activation syndrome and potential for cytokine- directed therapies. Annu

Rev Med. 2015; 66:145-59.

23. Schulert GS, Grom AA. Macrophage activation

syndrome and cytokine-directed therapies. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol.

2014; 28:277-92.

24. Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, Sanchez E,

Tattersall RS, Manson JJ, et al. COVID 19: Consider cytokine

storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020; 395:1033-34.

25. Pacha O, Sallman MA, Evans SE. COVID-19: A case

for inhibiting IL-17? Nat Rev Immunol. 2020; 20:345-46.

26. Acharyya BC, Acharyya S, Das D. Novel coronavirus

mimicking kawasaki disease in an infant. Indian Pediatr. 2020;

S097475591600184 [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 22].

27. Rauf A, Vijayan A, John ST, Hrishnan R, Latheef

A. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome with features of atypical Kawasaki

disease during COVID-19 pandemic. Indian J Pediatr. 2020;

S12098020033571 [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 28].

|

|

|

|

|