|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2021;58:1046-1051 |

|

Effect of Behavior

Change Communication on the Incidence of Pneumonia in Under Five

Children: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial

|

|

Jayashree Gothankar, 1

Prasad Pore,1 Girish

Dhumale,2 Prakash Doke,1

Sanjay Lalwani,3

Sanjay Quraishi,2 Sujata

Murarkar K,1 Reshma Patil,1

Vivek Waghachavare,2 Randhir

Dhobale,2 Kirti Rasote,2

Sonali Palkar1

From Departments of 1Community Medicine and 3Pediatrics, Bharati

Vidyapeeth Deemed to be University Medical College, Pune; and

2Department of Community Medicine, Bharati Vidyapeeth Deemed to be

University Medical College and Hospital, Sangli; Maharashtra.

Correspondence to: Dr Jayashree Gothankar, Department of Community

Medicine, Bharati Vidyapeeth Deemed to be University Medical College,

Off Pune Satara Road, Pune 411 043, Maharashtra.

Email: [email protected]

Received: November 25, 2020;

Initial review: February 25, 2021;

Accepted: August 18, 2021.

Trial Registration: CTRI/2017/12/010881

|

Background: Improving health education of the

mother by providing community-based interventions is known to help

control pneumonia.

Objective: To determine the effect of behavior

change communication (BCC) activities for mothers in reducing the

incidence of childhood pneumonia.

Design: Open-label cluster randomized controlled

trial.

Setting: Urban slums and villages in two districs

of Maharashtra.

Participants/Cluster: Under-five children and

their mothers from households in the randomly selected 16 clusters out

of total 45 clusters, stratified into Pune and Sangli districts and

further into rural and urban areas before randomization.

Intervention: Three forms of BCC activities were

imparted, viz., interactive sessions of education using pictorial

mothers’ booklet, screening of a audio-visual film, and virtual hand

wash demonstration and use of flashcard. Routine care under the National

health program was provided by the Accredited Social Health Activists

(ASHA) workers in both the arms.

Outcome: The primary outcome was pneumonia as per

the IMNCI criteria assessed during fortnightly visits of the ASHA/anganwadi

workers to the houses of under-five children, who received at least one

follow-up visit in a period of one year.

Results: The incidence of pneumonia in 1993 and

1987 under-five children in the intervention and control arm was 0.80

and 0.48 episodes per child per year, respectively (P=0.03).

Conclusion: BCC for mothers is not sufficient to

reduce the incidence of childhood pneumonia.

Keywords: Community intervention, Health education, Mothers,

Surveillance.

|

|

P

neumonia is one of the commonest cause of

under-five mortality [1] with estimates showing that 23% of

global pneumonia cases (around 43 million cases) occur in India

annually [2,3]. Lack of exclusive breastfeeding,

under-nutrition, low birth-weight, overcrowding, lack of

immunization and poor healthcare-seeking behavior are a few of

the leading risk factors for pneumonia in India and other low

and middle-income countries (LMICs) [4,5]. Only one in five

caregivers in the developing world know the two key symptoms of

pneumonia -fast and difficult breathing [6,7]. One of the

recommended critical activities in WHO’s and UNICEF’s Global

Action Plan for the Control of Pneumonia and Diarrhea is

improving health education of the mother by providing

community-based interventions (CBI) [8,9]. Our study was

conducted to determine the effect of behavior change

communication (BCC) activities directed at mothers in reducing

the incidence of childhood pneumonia.

METHODS

An open-label cluster randomized control

trial was conducted between December, 2015 and March, 2018 in

Pune and Sangli districts of Maharashtra in the urban and rural

field practice area of two medical colleges. Approval was

obtained from institutional ethics committee, and written

consent from the mothers was obtained prior to the enrolment.

Based on the reported incidence of childhood

pneumonia of 0.2-0.5 per child per year in under-five children

[10], and assuming the coefficient of variation (k) to be 0.4,

the sample size was calculated as 15 clusters.The study enrolled

sixteen clusters to cover for unforeseen eventualities

precluding the BCC activities in any cluster.

A cluster was defined as one of the 45

notified slums or revenue villages in the field practice area of

the two medical colleges. The 45 eligible clusters were first

stratified into two districts, further into urban and rural

clusters, urban clusters were stratified based on the East or

West. The rural clusters were stratified based on the primary

health center (PHC). These clusters were then randomized in to

intervention and control arms, based on a computer-generated

randomization schedule and two clusters per site were randomly

selected, thus 16 clusters were included. Participants were

under-five children and their mothers from the households in the

selected clusters (Web Fig.1).

Families residing for more than six months

with under-five children were included in the study. All the

under-five children and their mothers (including expectant

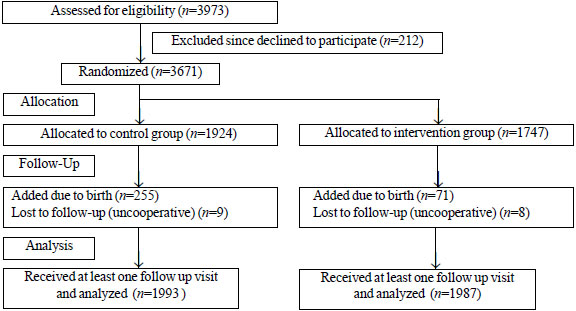

mothers) were enrolled as study participants. Fig. 1

shows the participant flow diagram. The new births were enrolled

throughout the trial period ensuring that they receive at least

nine months of surveillance. We excluded those children who

completed five years of age during the surveillance period from

further visits. All the children who had received at least one

follow-up visit were analyzed. The literacy status of the mother

was reported as per the census definition [11]. Ventilation

status of the house was assessed using the availability of per

capita floor space [12]. Due to the nature of the intervention

provided, allocation concealment and masking were not possible

after randomization.

|

|

Fig. 1 Study flow chart.

|

The total study period included the following

phases: preparatory (2 months), baseline survey and enrollment

(3 months), intervention (4 months), and surveillance (12

months).

The components of the BCC activities for the

mothers in the intervention arm consisted of imparting knowledge

about child feeding, including the importance of feeding of

colostrum, exclusive breastfeeding till six months of age,

gradual introduction of food from the age of six months, causes

of malnutrition among children, the importance of taking weight

and plotting of growth charts in anganwadi; imparting knowledge

about steps to prevent pneumonia in their children, such as

complete immunization, prevention of indoor air pollution, the

practice of cough etiquettes; hand hygiene including occasions

and steps of hand wash; and, providing information about the

signs and symptoms of pneumonia.

The BCC intervention was administered by

trained field supervisors to an invited group of 8-10 mothers at

a time, in an interactive manner using a validated mothers’

booklet, and a hand wash demonstration. The second BCC activity

was imparted by screening an audio-visual film for a larger

group of 15-20 mothers and virtual hand wash demonstration.

These two BCC activities were separated by a gap of two months.

ASHAs and anganwadi workers were involved in planning and

coordinating the BCC activities, thereby ensuring maximum

cooperation of the mothers. The third BCC or continued

intervention, through the house-to-house visit, was done three

months after the second BCC activity by using flashcards. A

total of eight trained field supervisors were involved in

imparting the BCC activities, under supervision of the site

investigators. Routine care under the national health program

was continued in both the arms of the study.

The primary outcome was the incidence of

pneumonia. Trained doctors confirmed the episode of pneumonia

using WHO Integrated management of neonatal and childhood

illnesses (IMNCI) guidelines [13]. The outcome was assessed by

fortnightly visits conducted for one year by the respective

ASHAs of each cluster, except in Pune (urban), where anganwadi

workers enquired about the current status of the child’s health

from the mother during the house-to-house surveillance visits.

For labeling a new episode of pneumonia in the same child, a

symptom-free period of a minimum of 14 days was considered

essential, otherwise, it was presumed to be continuation of the

preceding episode [14]. Besides, information about other

illnesses and death among under-five children was collected by

the field supervisors.

Quality checks were done randomly by site

investigators and field supervisors. Site investigators

conducted once-a-week field visits or as and when a case of

pneumonia was suspected. For data entry, the critical fields in

the tools were identified as a proxy to completeness and

accuracy – discrepancy up to 0.1% and 1%, respectively were

considered acceptable. Additionally, alternate forms were

physically cross-checked for discrepancies related to data

entry.

Statistical analysis: Intention to treat

analysis was done to analyze the incidence of pneumonia (as

episodes per child per year follow-up) in the intervention and

control arm. The relative risk was calculated to compare the

incidence between two arms. P value <0.05 was considered

statistically significant.

RESULTS

Sixteen clusters were randomly selected out

of the 45 clusters, eight were in the intervention arm, and

eight were in the control arm i.e., four in each urban and rural

area of the two districts. The under-five children enrolled in

the intervention arm were 1747 (20.1% aged <1 year) and in the

control arm 1924 (20.8% aged <1 year) (Fig. 1). A total

of 39 391 fortnightly follow-up visits were conducted in

intervention and 40 288 in the control arm during one year.

Baseline household and other demographic characteristics were

similar between the arms except for higher unclean fuel use in

control arm (20.1% vs 10.3%; P<0.05). Information related

to the child was obtained from the mothers i.e., exclusive

breast feeding for children between 6-12 months, primary

immunization for children between 12-24 months, birthweight for

children up to 6 months of age etc., hence the denominators

varied as per the number of mother-child in that group (Table

I).

Table I Baseline Characteristics of Households and Under-Five Children Enroled in the Study

| Characteristics |

Intervention arm

|

Control arm

|

|

n=1448 |

n=1374 |

| Household characteristics |

|

|

| Joint family |

871/1448 (60.2) |

812/1373 (59.1) |

| Hindu religion |

1278/1448 (88.3) |

1166/1374 (84.9) |

| SC/ST caste |

387/1448 (26.7) |

333/1374 (24.2) |

| Literate mother |

1295/1367(95.7) |

1334/1413(94.4) |

| Overcrowdinga |

906/1444(62.7) |

839/1371 (61.2) |

|

Inadequate ventilationb |

1349/1408 (95.8) |

1289/1315 (98.0) |

| Smoking indoor |

33/1442 (2.3) |

52/1368 (3.8) |

|

Unclean fuelc |

149/1448(10.3) |

277/1374(20.2) |

| Child characteristics |

n=1747 |

n= 1924 |

| Male sex |

925/1747(52.9) |

1014/1924(52.7 ) |

| Age (y)d |

2.38 (1.36) |

2.39 (1.37) |

| Birthweight (kg) |

2.51 (0.61) |

2.72 (0.60) |

|

(n=293) |

(n=371) |

|

Received colostrume |

313/330 (94.8) |

333/370 (90.0) |

| Exclusive breast- |

86/172 (46.0) |

111/249 (44.4) |

| feeding till 6 mo |

309/335 (92.2) |

296/304 (97.4) |

|

Fully immunizedf |

|

|

| Nutritional status of the child g |

|

|

| Wasting |

295/1678 (17.5) |

309/1852 (16.7) |

| Stunting |

720/1685 (42.7) |

916/1878 (48.8) |

| Undernutrition |

565/1693 (33.3) |

694/1864 (37.2) |

|

Date presented as number/total number (%). aNumber of

family members per room criteria was used; bInadequate

ventilation was defined as households with less than 100

sq. ft. of floor area per person with, or without a fan;

cUnclean fuel included biomass, coal stove, stove with

kerosene for cooking purposes for most of the days of

the week by the household; dThis information was

collected from mothers of infants upto one year of age

only to remove the possibility of recall bias, and the

intention was to assess the most essential i.e., primary

immunization; eInformation was analyzed for

infants between >6 mo to one year of age only;

fImmunization information was analyzed for children with

cards and aged between 12-23 months. gWHO classification

was used; results presented for <-2SD. Child

characteristics are based on children enrolled during

baseline phase only. |

There were a total of 5505 episodes of

illnesses in the intervention arm and 6436 episodes in the

control arm. Of these, there were 44 and 31 episodes of

pneumonia in the intervention and control arm, respectively,

constituting an incidence of 0.80 and 0.48 episodes of pneumonia

per child per year, respectively in the two arms [RR (95% CI)

1.66 (1.05-2.62); P=0.03]. Three children in the

intervention and two in the control arm had two episodes each.

There was no case of severe pneumonia and very severe disease.

Twenty-six (59.1%) episodes in inter-vention arm and 21 (67.7%)

episodes in control arm were reported in boys [RR (95% CI)

0.87(0.62-1.23); P=0.77]. For 93.2% of pneumonia episodes

in the intervention arm, children were taken to the health care

provider as the first action, in contrast to 54.9% from the

control arm [(RR (95% CI) 5.06 (2.58 to 9.92); P<0.001)]

(Table II). None of the children required hospitalization

for pneumonia in both the arms. There were two deaths reported

in each study arm, unrelated to pneumonia. The number of

pneumonia episodes was highest in the winter season (51%).

Table II Episodes of Common Illnesses in the Intervention and Control Groups

|

Illnesses/action taken |

Intervention arm,

n=1747

|

Control arm, n=1924 |

RR(95% CI) |

P value |

|

Number of |

Incidence |

Number of |

Incidence |

|

|

|

episodes |

(per child per y) |

episodes |

(per child per y) |

|

|

| Total illness

episodes documented /total visits |

5505/39391 |

13.98 |

6436/40288 |

15.97 |

— |

— |

| Pneumonia |

44 |

0.80 |

31 |

0.48 |

1.66 (1.05 to 2.62) |

0.030 |

| Cold/cough

|

2738 |

49.74 |

2770 |

43.0 |

1.15 (1.11 to 1.20) |

<0.001 |

| Diarrhea |

128 |

2.32 |

242 |

3.76 |

0.62 (0.50 to 0.76) |

<0.001 |

| Vomiting |

52 |

0.94 |

88 |

1.37 |

0.69 (0.49 to 0.97) |

0.03 |

|

Contacting a HCPa |

41/44 |

- |

7/31 |

- |

5.06 (2.57 to 9.92) |

<0.001 |

|

Symptoms were assessed from mothers of the

children,only pneumonia was diagnosed using IMNCI

criteria. aContacting a health care provider as a first

action taken in case of pneumonia episodes. |

Out of all the episodes of illness, diarrhea

contributed to 2.32 and 3.76 episodes per child per year in the

intervention and control arm, respectively (P <0.001).

DISCUSSION

Our study shows that the incidence of all

illnesses taken together, was significantly less with BCC

intervention. The low incidence of pneumonia in both the arms of

the study was comparable to that reported in South East Asian

countries [10,13]. This low incidence may reflect the fact that

Maharashtra has better health indicators, compared to other

states of India [14]. A three-year follow-up study completed in

2008 in a Southern state of India reported an incidence rate of

0.4 (95% CI=0.3-0.7) in its first year [15]. However, the

incidence of pneumonia in the current study was higher in

children less than one year of age compared to those in 1-5 year

age group, similar to the findings reported by other studies

[16,17].

Like other studies, the fortnightly follow-up

visits in the current study, for one calendar year, took into

account the seasonal variation in the incidence of pneumonia

[18,15]. Possibly, a more extended follow-up period or

revisiting the clusters after a gap of two years might be

required to observe benefits from these activities on health

outcomes [19]. Though the WHO IMNCI tool for confirming

pneumonia lacks specificity, it is the best measure of reporting

pneumonia in children under five years of age [20]. The

possibility of overdiagnosis of pneumonia by non-physician

healthworkers was addressed by confirmation of these episodes by

an expert. The seasonal trend of pneumonia in the current study

was similar to those reported by other studies [15,21,22].

The care-seeking pattern for illness was

similar in both groups with the commonest healthcare provider

contacted being private practitioners. These findings are

similar to other studies in India [23-26]. The current study

reported fewer hospital admissions for pneumonia compared to

other studies in India [15]. It may be due to early case

detection and ambulatory management of pneumonia. Another study

from India had concluded that trust in the public health system

is essential for making the community-based pneumonia management

program successful [27].

The overall morbidity and diarrheal episodes

during follow-up were less than other studies in India [20]. The

incidence of pneumonia was slightly higher in the intervention

than the control arm, probably reflecting higher reporting by

mothers about illness episode in their children in the

intervention arm than in the control arm. There were

significantly fewer diarrhea episodes in the intervention arm

than in the control arm.

The current study has the potential for

generalizability as the community health workers i.e., ASHA and

anganwadi workers, were involved in surveillance visits.

Routinely, ASHA and Anganwadi workers deliver incentive-based

maternal and child health - related work, but in this trial,

they received surveillance-related training, enabling them to

timely identify sickness in a child as recommended by WHO [28].

It also helped to gain cooperation from mothers and other family

members. However, external validity is limited to states with

similar health parameters. BCC may be valuable in states with

high under-five mortality, but further studies need to be

conducted in these states. The limitation of the present study

was a relatively short follow-up duration, which may be

inadequate to observe the impact of BCC activities.

BCC alone is unlikely to be effective for the

reduction of the incidence of pneumonia. The reduction in the

incidence of pneumonia is influenced by factors such as economic

status, birthweight, overcrowding, joint family, type of fuel,

etc. So, intervention in the form of BCC activity may need

support of additional strategies to reduce the incidence of

pneumonia.

Acknowledgments: Dr Nandini Malshe for

her technical inputs. Mrs. Aruna Deshpande, Mr Sane, Statistical

consultant; Mrs. Mahima Dwivedi and Dr. Supriya Phadnis, Project

coordinators for their inputs in project implementation and

report compilation; Dr. V N Karandikar, Ex-Director Health

Sciences of Bharati Vidyapeeth University Pune; Dr. Manoj Das,

INCLEN Trust International for technical guidance.

Ethics clearance: Bharati Vidyapeeth

Deemed University Institutional Ethics Committee; No.

ECR/313/Inst/MH/2013/RR-16 dated February 16, 2015. Bharati

Vidyapeeth Deemed University Medical College and Hospital IEC,

Sangli; No. ECR/276/Inst/MH/2013/RR-16 dated March 01, 2015.

Contributors: JG, PD, PP, GD, SL:

conceptualization; JG, PP, GD: data curation; JG, PP, GD, PD:

formal analysis; JG, SK, PD: funding acquisition; JG, PD, PP,

GD: methodology; JG, GD, PP, SP: project administration; SL, JG,

PD: resources; PP, VW: software; SQ, SM, RP, VW, RD, KR, SP:

supervision; JG, PD, SL: validation; JG, PP: writing – original

draft preparation; JG, PD: Writing – review and editing. All

authors approved the final version of manuscript, and are

accountable for all aspects related to the study.

Funding: This work was supported by Bill

and Melinda Gates Foundation through The INCLEN Trust

International (Grant number: OPP1084307). The funding source had

no contribution in study design, implementation, collection and

interpretation of data and report writing. Competing

interest: None stated.

Note: Additional material related

to this study is available with the online version at

www.indianpediatrics.net

| |

|

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN?

• Behavior change communication (BCC)

interventions, alongwith efforts towards improving the

immunization status of children and breastfeeding

promotion, are documented to be efficient,

cost-effective, and sustainable interventions in

reducing the burden of childhood pneumonia.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS?

• BCC intervention alone, aimed towards mothers, was

not found to be sufficient to reduce the incidence of

pneumonia in under-five children.

|

REFERENCES

1. Million Death Study Collaborators.

Causes of neonatal and child mortality in India: a

nationally representative mortality survey. Lancet.

2010;376:1853-60.

2. Rudan I, O’Brien KL, Nair H, et al.

Epidemiology and etiology of childhood pneumonia in 2010:

Estimates of incidence, severe morbidity, mortality,

underlying risk factors and causative pathogens for 192

countries. J Glob Health. 2013;3:010401.

3. Watt JP, Wolfson LJ, O’Brien KL, et

al. Burden of disease caused by Haemophilus influenzae type

b in children younger than 5 years: Global estimates.

Lancet. 2009; 374:903-11.

4. Farooqui H, Jit M, Heymann DL, Zodpey

S. Burden of severe pneumonia, pneumococcal pneumonia and

pneumonia deaths in Indian states: Modelling based

estimates. PLoS One. 2015;10:1-11.

5. Walker CLF, Rudan I, Liu L, et al.

Global burden of child- hood pneumonia and diarrhoea.

Lancet. 2013; 381:1405-16.

6. Cohen AL, Hyde TB, Verani J, Watkins

M. Integrating pneumonia prevention and treatment

interventions with immunization services in resource-poor

countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90:289-94.

7. Mull DS, Mull JD, Kundi MM, Anjum M.

Mothers’ perceptions of severe pneumonia in their own

children: a controlled study in Pakistan. Soc Sci Med.

1994;38:973-87.

8. Qazi S, Aboubaker S, MacLean R, et al.

Ending preventable child deaths from pneumonia and diarrhoea

by 2025. Development of the integrated global action plan

for the prevention and control of pneumonia and diarrhoea.

Arch Dis Child. 2015;100:S23-8.

9. Van Ginneken JK, Lob Levyt J, Gove S.

Potential interventions for preventing pneumonia among young

children in developing countries: promoting maternal

education. Trop Med Int Health. 1996;1:283-94.

10. Ghimire M, Bhattacharya SK, Narain

JP. Pneumonia in South-East Asia region: Public health

perspective. Indian J Med Res. 2012;135:459-68.

11. Government of India. Census of India

2011 [Internet]. Accessed October 5, 2020. Available from:

https://censusindia.gov.in/2011-common/censusdata2011.html

12. Park K. Park’s Textbook of Preventive

and Social Medicine. 24th ed. Banarasidas Bhanot publishers;

2017. p.775-76.

13. Rudan I, Tomaskovic L, Boschi-Pinto

C, Campbell H. Global estimate of the incidence of clinical

pneumonia among children under five years of age. Bull World

Health Organ. 2004;82:895-903.

14. Ram F, Paswan B, Singh SK, et al.

Improvements in maternal health in India: Evidence from

NFHS-4 ( 2015-16). Demography India. 2016; 43.

15. Gladstone BP, Das AR, Rehman AM.

Burden of illness in the first 3 years of life in an Indian

slum. J Trop Pediatr. 2010;56:221-6.

16. Bari A, Sadruddin S, Khan A. Cluster

randomized trial of community case management of severe

pneumonia with oral amoxicillin in children 2-59, Pakistan.

Lancet. 2011; 378:1796.

17. Luby SP, Agboatwalla M, Feikin DR,

Painter J, Billhimer W, Altaf A, et al. effect of

handwashing on child health: A randomized controlled trial.

Lancet. 2005;366:225-33.

18. Lanata CF, Rudan I, Boschi-Pinto C,

et al. Methodological and quality issues in epidemiological

studies of acute lower respiratory infections in children in

developing countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33:1362-72.

19. Boone P, Elbourne D, Fazzio I, et al.

Effects of community health interventions on under-5

mortality in rural Guinea-Bissau (EPICS): A

cluster-randomized controlled trial. Lancet Glob Health.

2016;4:e328-35.

20. Mortimer K, Ndamala CB, Naunje AW, et

al. A cleaner burning biomass-fuelled cookstove intervention

to prevent pneumonia in children under 5 years old in rural

Malawi (the Cooking and Pneumonia Study): A cluster

randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389:167-75.

21. Montella S, Corcione A, Santamaria F.

Recurrent pneumonia in children: A reasoned diagnostic

approach and a single centre experience. Int J Mol Sci.

2017;18:296.

22. Smith KR, Samet JM, Romieu I, Bruce

N. Indoor air pollution in developing countries and acute

lower respiratory infections in children. Thorax.

2000;55:518-32.

23. Minz A, Agarwal M, Singh JV, Singh

VK. Care seeking for childhood pneumonia by rural and poor

urban communities in Lucknow: A community-based

cross-sectional study. J Family Med Primary Care. 2017;6:

211-7

24. Soni A, Fahey N, Phatak AG, et al.

Differential in healthcare-seeking behavior of mothers for

themselves versus their children in rural India: Results of

a cross sectional survey. International Public Health

Journal. 2014;6:57.

25. Bhandari N, Mazumder S, Taneja S,

Sommerfelt H, Strand TA. Effect of implementation of

Integrated Management of Neonatal and Childhood Illness

(IMNCI) programme on neonatal and infant mortality: cluster

randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2012;344:e1634

26. Das JK, Lassi ZS, Salam RA, Bhutta

ZA. Effect of community based interventions on childhood

diarrhea and pneumonia: uptake of treatment modalities and

impact on mortality. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1-0.

27. Awasthi S, Nichter M, Verma T, et al.

Revisiting community case management of childhood pneumonia:

Perceptions of caregivers and grass root health providers in

Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, Northern India. PLoS One.

2015;10:1-18.

28. Revised WHO Classification and Treatment of Pneumonia in

Children at Health Facilities: Evidence Summaries. World Health

Organization; 2014. Accessed on Oct 5, 2020. Avail-able from:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK264162/

|

|

|

|

|