|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2012;49:

881-887 |

|

Disease Course in Steroid Sensitive Nephrotic

Syndrome

|

|

Aditi Sinha, Pankaj Hari, Piyush Kumar Sharma, Ashima Gulati, Mani

Kalaivani*, Mukta Mantan, Amit Kumar Dinda †,

Rajendra N Srivastava and Arvind Bagga

From Departments of Pediatrics, *Biostatistics and

†Pathology, All India Institute of Medical

Sciences, New Delhi, India.

Correspondence and offprint requests to: Prof. Arvind

Bagga, MD, Department of Pediatrics, All India Institute

of Medical Sciences, Ansari Nagar, New Delhi 110029, India.

Email: [email protected]

Received: December 7, 2011;

Initial review: December 23, 2011;

Accepted: February 10, 2012.

Published

online: 2012, March 30.

PII:S097475591100999-1

|

Objective: To review the disease course in patients with steroid

sensitive nephrotic syndrome (SSNS) and the factors that determine

outcome

Design: Retrospective, analytical

Setting: Pediatric Nephrology Clinic at referral

center in North India

Participants/patients: All patients with SSNS

evaluated between 1990 and 2005

Intervention: None

Main outcome measures: Disease course, in

patients with at least 1-yr follow up, was categorized as none or

infrequent relapses (IFR), frequent relapses or steroid dependence (FR),

and late resistance. Details on complications and therapy with

alternative agents were recorded.

Results: Records of 2603 patients (74.8% boys)

were reviewed. The mean age at onset of illness and at evaluation was

49.7±34.6 and 67.5±37.9 months respectively. The disease course at 1-yr

(n=1071) was categorized as IFR in 37.4%, FR in 56.8% and late

resistance in 5.9%. During follow up, 224 patients had 249 episodes of

serious infections. Alternative medications for frequent relapses (n=501;

46.8%) were chiefly cyclophosphamide and levamisole. Compared to IFR,

patients with FR were younger (54.9±36.0 vs. 43.3±31.4 months),

fewer had received adequate ( ³8

weeks) initial treatment (86.8% vs. 81.7%) and had shorter

initial remission (7.5±8.6 vs. 3.1±4.8 months) (all P<0.001).

At follow up of 56.0±42.6 months, 77.3% patients were in remission or

had IFR, and 17.3% had FR.

Conclusions: A high proportion of patients with

SSNS show frequent relapses, risk factors for which were an early age at

onset, inadequate initial therapy and an early relapse.

Keywords: Frequent relapses; Minimal change disease; Steroid

dependent nephrotic syndrome.

|

|

The course of illness in

children with steroid sensitive nephrotic syndrome varies from a single

episode to infrequent or frequent relapses, and rarely the occurrence of

late steroid resistance [1,2]. The management of patients with frequent

relapses, steroid dependence and late resistance is difficult, often

requiring the use of alternative agents. Information on the course of

nephrotic syndrome is available from multiple cohorts, including that of

the International Study of Kidney Diseases in Children (ISKDC) [1,3-6].

Risk factors for frequent relapses include an early age of onset, short

initial therapy, delayed time to remission and brief duration of the

first remission [1,7-11]. An understanding of factors that determine the

course is useful in decisions regarding therapy and enables counseling.

In 1975, we described our experience on the clinical

features and renal histology in 206 consecutive patients with nephrotic

syndrome [12]. The findings suggested that clinical and histological

features of nephrotic syndrome in Indian children were similar to that

reported elsewhere [1]. While the management of the initial episode and

choice of alternative medications have changed over the years, there is

limited contemporary data on the outcomes. We reviewed the case notes of

recent patients, in order to examine the course of illness and its

determinants.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed the records of all

patients with idiopathic steroid sensitive nephrotic syndrome, having an

Indian ancestry, who presented to this center between 1990 and 2005.

Children with onset of illness after 15-years, congenital nephrotic

syndrome (onset <3-months of age) or known to be secondary to infections

or systemic disease, or estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR)

£60 mL/min/1.73

m2 at evaluation were

excluded.

Disease course

The disease course, use of alternative therapies and

complications were described for patients with minimum 12-months follow

up at this center (Study Group). The course of disease during

these 12 months was categorized as single episode, infrequent relapses,

frequent relapses, steroid dependence or late resistance. Frequent

relapses was defined as the occurrence of ≥2 relapses in 6

months or

≥3

relapses in 12 months, and steroid dependence as the presence of two

consecutive relapses while on tapering doses of prednisolone [13].

Failure to show remission of proteinuria despite 4-weeks treatment with

prednisolone (2 mg/kg/day) was termed as initial resistance

when noted at onset of disease, and late resistance if occurring

in a patient previously responsive to steroids [13].

Hypertension was defined as blood pressure higher

than 95 th percentile for

sex, age and height [14]. Short stature was height less than 2 standard

deviations (SD) and obesity was body mass index more than 3 SD of

expected [15]. Patients had regular examination for visual acuity,

intraocular pressure and cataract. Standard definitions were used for

systemic infections [13]. Tuberculosis was diagnosed if the tuberculin

test was positive (induration ≥10 mm at 48 hr) in presence of

clinical and radiological features.

Therapy

Until 1992, patients at the first episode of

nephrotic syndrome were treated with daily prednisolone for 4 weeks

followed by alternate day therapy for 4 weeks. Between 1992 and 1995,

patients participating in a randomized controlled trial received the

aforementioned 8-weeks or prolonged 16-weeks treatment [16]. Thereafter,

patients have received therapy with daily and alternate day prednisolone

for 6 weeks each. For purpose of this review, adequate initial

treatment was the use of prednisolone (2 mg/kg/day) for

≥4 weeks followed by

1.5 mg/kg on alternate days for

≥4

weeks. Relapses were treated with prednisolone, 2 mg/kg/d until

remission and 1.5 mg/kg on alternate days for 4 weeks.

Patients with frequent relapses or steroid dependence

received prednisolone (0.3-0.7 mg/kg) on alternate days for 9-12 months.

Those having relapses or steroid toxicity received one or more

alternative agents [13], often as follows: (i) levamisole (2

mg/kg on alternate days); (ii) oral cyclophosphamide (2 mg/kg/d

for 12 weeks); (iii) mycophenolate mofetil (600-1000 mg/m 2/d);

(iv) cyclosporine (4-6 mg/kg/d) or tacrolimus (0.1-0.2 mg/kg/d).

Kidney biopsies were done in patients with persistent

hematuria, deranged renal function, steroid resistance or prior to

therapy with calcineurin inhibitors, and examined by light microscopy

and immunofluorescence [17].

Statistical analysis: Data from eligible patients

with steroid sensitive illness was used to compute baseline features.

Characteristics of patients in the Study Group were compared between the

infrequent relapsers (patients with single episode or infrequent

relapses) and frequent relapsers (frequent relapses or steroid

dependence). Analyses were performed using Stata 11 (Statacorp, College

Station, TX). Summary statistics were expressed as means and SD; groups

were compared using Student’s t test and Chi square test. On logistic

regression, risk factors were reported as odds ratio (OR) with 95%

confidence interval (CI). For this purpose, certain variables were

dichotomized based on information from previous studies [1,3,8,18,19].

These included the age at onset (<4 yr or

≥4 yr); duration of

initial therapy (<8 weeks or

≥8

weeks) and duration of remission following therapy of the initial

episode (<6 months or

≥6

months).

Results

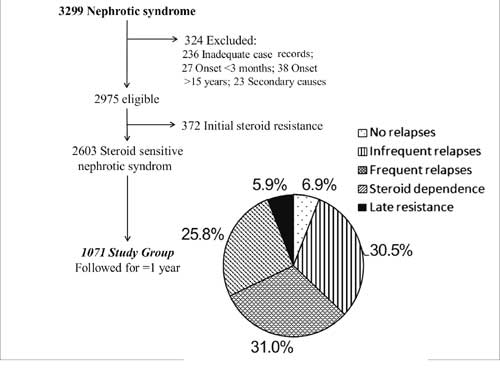

Of 3299 patients with nephrotic syndrome, 324 were

excluded due to inadequate case records, age of onset >15 yr or presumed

secondary etiology (Fig. 1). Initial steroid resistance

was noted in 372 (12.5% of 2975) patients. Details on baseline

characteristics were available in 2603 patients with steroid sensitive

nephrotic syndrome (Table I). Most patients had received

adequate initial therapy with prednisolone and over one-half received

treatment for 12 weeks. The duration of initial remission was 4.6±6.4

months. Renal biopsies, in 341 patients, showed minimal change disease

in 242 (70.9%), mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis in 48 (14.1%)

and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in 51 (15.0%).

|

|

Fig. 1 Flow chart showing patients

with nephrotic syndrome. The course of disease in patients with

minimum 12-months follow up at this center (Study Group) is

depicted.

|

TABLE I Baseline Features of Patients with Steroid Sensitive Nephrotic Syndrome

|

All patients;

|

Study Group;

|

|

N=2603 |

N=1071 |

|

Boys |

1947 (74.8%) |

816 (76.2%) |

|

Age at onset, mo

|

49.7 ± 34.6 |

48.7 ± 34.4 |

|

Age at evaluation, mo

|

67.5 ± 37.9 |

67.4 ± 39.2 |

|

Family history of disease |

46 (1.8) |

15 (1.4) |

|

Hematuria |

242 (9.3) |

85 (7.9) |

|

Hypertension |

97 (3.7) |

35 (3.3) |

|

Blood investigations

|

|

Creatinine, mg/dL

|

0.71 ± 0.34 |

0.70 ± 0.31 |

|

Albumin, g/dL

|

2.3 ± 0.9 |

2.2±0.9 |

|

Cholesterol, mg/dL |

343.2 ± 122.0 |

344.7 ± 122.6 |

|

Initial prednisolone therapy

|

|

Total duration, wks

|

13.6 ± 6.2 |

13.2 ± 6.2 |

|

Adequate therapy (³8 wks) |

2193 (84.3)

|

901 (84.1) |

|

8-11 wks

|

699 (26.9) |

318 (29.7) |

|

≥12 wks |

1494 (57.4) |

583 (54.4) |

|

Duration of initial remission (mo) |

4.6 ± 6.4 |

4.8 ± 7.0 |

|

Continuous variables are denoted as mean±standard deviation (95%

ci), categorical variables as n (%) |

Study Group

Of all patients with steroid sensitive nephrotic

syndrome, 1071 (41.2%) having minimum 12-months follow up at this center

constituted the Study Group. Following a mean age of onset of 48.7±34.4

months, and initial remission of 4.8±7.0 months, the age at evaluation

was 67.4±39.2 months (Table 1). At follow up of 12 months, the disease

course was categorized as none or infrequent relapses in 37.4%, frequent

relapses or steroid dependence in 56.8% and late resistance in 5.9% (Fig.

1).

Within the Study Group, 312 patients (237 boys;

76.0%) had been followed since onset of nephrotic syndrome. Their age at

onset was 46.7±33.9 months, and disease course during 12-months was

defined as none or infrequent relapses in 46.8%, frequent relapses in

49% and late resistance in 4.2%.

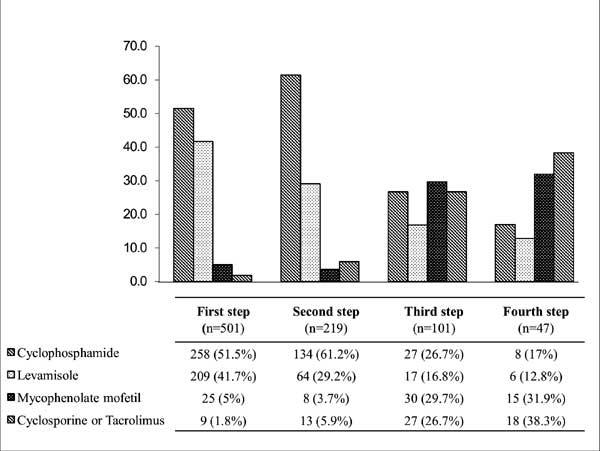

Alternative medications: These were administered

for frequent relapses in 501 (46.8%) patients. Two, three and four

medications were required in 219 (20.5%), 101 (9.4%) and 47 (4.4%)

instances respectively (Fig. 2). Most patients received

therapy with oral cyclophosphamide or levamisole initially, followed by

mycophenolate mofetil or a calcineurin inhibitor.

|

|

Fig. 2 Alternative medications

for patients with frequent relapses or steroid dependence in the

Study Group. Heights of individual bars represent the

proportions of patients receiving the medication at each step of

therapy. The number (%) of patients is shown in the panel below.

|

Complications: A significant proportion of

patients in the Study Group showed adverse effects of corticosteroid

therapy. During a mean follow up of 56.0±42.6 months, 224 patients had

249 episodes of serious infections, which required hospitalization.

These included peritonitis (7.7%), pneumonia (5.3%), cellulitis

(3.7%), diarrheal dehydration (2.2%), urinary tract infections (2.1%)

and tuberculosis (1.8%). Sequelae of corticosteroid therapy included

obesity (n=226, 21.1%), hypertension (n=62, 5.8%),

stunting (n=53, 4.9%) and cataract (n=17, 1.6%). Behavior

abnormalities and thrombosis were observed in 38 (3.6%) and 4 (0.4%)

patients. Patients with frequent relapses had a significantly higher

risk of serious infections (OR 2.37; 95% CI 1.66, 3.39), obesity (OR

2.70; 1.92, 3.80), stunting (OR 2.64; 1.45, 4.79) and hypertension (OR

2.22; 1.14, 4.33).

TABLE II Characteristics of Infrequent Relapsers, Frequent Relapsers and Patients With Late Resistance

|

Infrequent relapsers† |

Frequent relapsers‡ |

Late resistance,

|

|

n=400 |

n=608 |

n=63

|

|

Boys |

306 (76.5)

|

474 (77.9)

|

44 (69.1) |

|

Age at onset, mo

|

54.9 ± 36.0 (51.6, 58.1) |

43.3 ± 31.4 (40.6, 46.0)** |

47.9 ± 39.3 (37.2, 58.5) |

|

Family history of disease |

6 (1.5) |

9 (1.5) |

0 (0) |

|

Hematuria at onset |

34 (8.5) |

41 (6.7) |

10 (15.9)#$ |

|

Investigations

|

|

Creatinine, mg/dL |

0.67 ± 0.23 (0.59, 0.72) |

0.64 ± 0.42 (0.57, 0.68) |

0.79 ± 0.77 (0.56, 1.03)

|

|

Albumin, g/dL

|

2.3 ± 0.9 (2.2, 2.4) |

2.2 ± 0.9 (2.2, 2.3) |

2.2 ± 0.8 (1.9, 2.4) |

|

Cholesterol, mg/dL |

347.3 ± 123.9 (331, 363) |

346.8 ± 121.7 (335, 359) |

328.4 ± 129.4 (286, 371) |

|

Initial steroid therapy

|

|

Total duration, wks |

13.7 ± 6.2 (13.1, 14.2) |

12.8 ± 6.1 (12.2, 13.3)* |

14.3 ± 7.4 (12.3, 16.4)

|

|

Adequate therapy (>8 wks) |

347 (86.8) |

490 (81.7)* |

53 (84.1) |

|

Duration of initial remission, mo |

7.5 ± 8.6 (6.5, 8.5) |

3.1 ± 4.8 (2.6, 3.5)** |

3.9 ± 7.7 (1.2, 6.5)## |

†Single episode or infrequent relapses; ‡Frequent relapses or

steroid dependence; Continuous variables are denoted as

mean±standard deviation (95% CI), categorical variables as n

(%); Difference between infrequent relapsers and frequent

relapsers: *P<0.05; **P<0.001; Difference between infrequent

relapsers and late resistance: #P<0.05,

##P <0.001; Difference between frequent relapsers and

patients with late resistance: $P<0.05. |

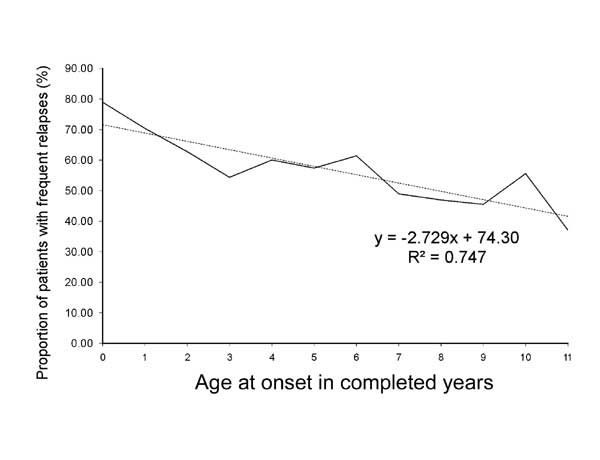

Risk factors for disease course: Table

II compares the characteristics of the frequent (n=608) and

infrequent relapsers (n=400). The former were younger at onset of

the disease (mean difference 11.5 months; 95% CI 7.3, 15.8 months; P<0.001)

and the proportion of patients with frequent relapses declined with

increasing age (Fig. 3). The duration of initial therapy

was short in frequent relapsers compared to those with infrequent

relapses (mean difference 0.9 weeks, 95% CI 0.1, 1.6 weeks; P=0.02).

A significantly lower proportion of frequent relapsers had received

adequate ( ³8

weeks) initial steroid therapy. Initial therapy for

³12 weeks was

associated with an additional 30% reduced risk of frequent relapses

compared to those treated for 8-11 weeks (OR 0.70; 95% CI 0.51, 0.95;

P=0.02). Frequent relapsers also had brief initial remission,

compared to those with infrequent relapses (mean difference 4.5 months;

95% CI 3.4, 5.5 months; P <0.001).

|

|

Fig. 3 Proportion of patients with

frequent relapses or steroid dependent nephrotic syndrome in

relation to the age at onset of the illness.

|

On univariate and multivariate logistic regression,

young age at onset (<4 yr), lack of adequate initial therapy (<8 weeks)

and short duration of initial remission (<6 months) were each associated

with significantly increased risk of frequent relapses (Table

III).

TABLE III Risk Factors for Frequent Relapses (N=1071)

|

Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|

Unadjusted |

P |

Adjusted |

P |

|

Age at onset ≥4 y |

0.64 (0.49, 0.85) |

0.002 |

0.62 (0.43, 0.90) |

0.01 |

|

Initial therapy ≥8 weeks

|

0.61 (0.41, 0.91) |

0.015 |

0.55 (0.33, 0.92) |

0.02 |

|

Initial remission ≥6 months |

0.17 (0.11, 0.25) |

<0.001 |

0.18 (0.11, 0.27) |

<0.001 |

Late resistance: Of 1071 patients, 63 (5.9%)

showed late resistance. The presence of hematuria (gross 7; microscopic

3) (Table II) was independently associated with late

steroid resistance (OR 3.3, 95% CI 1.4, 8.1; P=0.007).

Compared to patients with infrequent relapses, the duration of initial

remission was shorter (mean difference 3.7 months, 95% CI 0.7, 6.7

months; P=0.02). Renal histology (n=54) showed

focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in 25 (46.3%), minimal change disease

in 22 (40.7%) and mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis in 7 (13%).

Therapies included cyclosporine or tacrolimus in 40 (63.5%) patients and

IV cyclophosphamide in 23 (36.5%) patients; complete or partial

remission was seen in 39 (61.9%).

Outcome

Table IV shows the outcome of patients at

last follow up at 56.0±42.6 (range 12-160) months. Infrequent relapses

or sustained remission was seen in 828 (77.3%) patients, 185 (17.3%) had

frequent relapses or steroid dependence, and 42 (3.9%) showed late

steroid resistance. Most patients (89.8%) with infrequent relapses at

initial evaluation were in remission or had infrequent relapses. The

outcome in patients with frequent relapses or steroid dependence was

also satisfactory; 72.0% had remission or infrequent relapses and 23.8%

persisted with frequent relapses. At last follow up, 53.8% of 145

patients with frequent relapses continued to require alternative

immunosuppressive agents, most commonly levamisole (n=37) or

cyclophosphamide (n=23), while others (n=67, 46.2%) were

receiving low dose prednisolone on alternate days. A small proportion

(2%) having late steroid resistance was managed chiefly with calcineurin

inhibitors.

TABLE IV Outcome of Patients at Last Follow up (N=1071) in Relation to Initial Course.

|

Outcome at last follow up |

Infrequent relapses (n=400),

|

Frequent relapses (n=608),

|

Late resistance

|

|

No (%) |

No (%) |

(n=63) |

|

Sustained remission, infrequent relapses

|

359 (89.8) |

438 (72.0) |

31 (49.2) |

|

Frequent relapses, steroid dependence

|

32 (8.0) |

145 (23.8) |

8 (12.7) |

|

Late steroid resistance

|

9 (2.3) |

12 (2.0) |

21 (33.3) |

|

Died |

0

|

13 (2.1) |

3 (4.8) |

A significant proportion of patients (33.3%) with

late resistance had persistent nephrotic range proteinuria. In patients

with late resistance, the course of illness was similar in those with

focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, minimal change disease and

mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis (data not shown). Sixteen

(1.5%) patients, with either frequent relapses or late resistance, died

of complications of severe infections. Eleven deaths occurred in

patients admitted with refractory septic shock following pneumonia (n=5),

diarrhea (n=3), meningitis with severe pneumonia (n=1) or

fever without focus (n=2). Five children died at home with

probable diagnosis of severe pneumonia.

Discussion

We report the course of illness in a large group of

patients with steroid sensitive nephrotic syndrome seen at a tertiary

care center in India during 1990 to 2005. Data from 1071 patients, with

minimum follow up of 12 months, was used to determine the course and

risk factors associated with frequent relapses. During this period,

practices regarding diagnosis and therapy were relatively constant,

except that MMF and tacrolimus were included as alternative agents after

1998. These findings are important since they reflect outcomes of

existing practice, as compared to most previous reports that include

data on patients diagnosed during 1970-80 [1,3-6,12].

The characteristics of our patients were similar to

that reported previously including age at onset, male preponderance and

low incidence of familial cases [1,12, 20]. The proportion of patients

having initial and late resistance was 12.5% and 5.9% respectively,

confirming previous findings [3,5,21]. While the ISKDC reported that

just 28.1% patients show frequent relapses in the first 6 months of

their illness [3], data from other centers, comprising relatively small

numbers of patients, shows that the proportion of frequent relapsers

varies from 56-68% [8,10-11]. The present case series suggests that,

despite 2-3 years from onset, frequent relapsers constitute more than

one-half of all patients. While this information might suggest a

referral bias, it is notable that 49% of the 312 patients followed at

this center since onset of disease had frequent relapses. The reasons

for detecting a high proportion of patients with frequent relapses are

unclear, but might reflect biologic variations in disease severity or

the increased occurrence of infection induced relapses [22].

There is evidence that adequate initial therapy with

corticosteroids is useful in reducing the risk of subsequent relapses

[23]. The present study also suggests that extension of initial therapy

to 8-11 weeks was associated with reduced proportion of patients with

frequent relapses; those receiving therapy for

≥12 weeks had an

additional 30% lower risk. While data from prospective studies, reviewed

recently [24], emphasize the benefits of prolonged therapy, its optimal

duration is not known and is being addressed in randomized controlled

trials.

Findings from the present study confirm that an early

age at onset of nephrotic syndrome is associated with risk of frequent

relapses [8,18,25]. Based on an age cut-off proposed in previous

studies, we found that patients with onset of illness beyond 4-yr had a

38% lower risk of frequent relapses as compared to younger children.

However, data from the ISKDC cohort [1] and others [10, 11] do not

report an association between age at onset and the occurrence of

frequent relapses. Finally, the risk of frequent relapses was reduced by

82% in children with initial remission lasting 6 months of longer,

supporting findings of the ISKDC report [1] and of Fujinaga, et al.

[19].

Almost one-half of the patients, who were followed

up, required alternative medications for frequent relapses. Conforming

to national guidelines and similar to practices elsewhere,

cyclophosphamide and levamisole were the preferred first-line therapies,

while the use of calcineurin inhibitors and mycophenolate mofetil was

limited [13,26]. The diminishing numbers of patients requiring

alternative medications at each step (Fig. 2) reflects the

changes in disease course with therapy and time. Our experience on the

impact of these treatment regimens has been reported earlier [27-29].

Long-term follow up of the ISKDC cohort, 9 years from

the onset, suggests that the tendency to relapse reduces with time, and

that most patients had either sustained remission or infrequent relapses

[3]. Five years after diagnosis, almost three-fourth patients in the

present study showed such a course, and only one-fifth continued to

either relapse frequently or had unremitting proteinuria. The outcomes

were similar in patients with frequent relapses and steroid dependence

(data not shown). Koskimies, et al similarly reported

sustained remission in 78.7% of 94 steroid sensitive patients at 5-14 yr

follow up [5]. In a cohort of 132 children, followed over 27 years,

Wynn, et al. found sustained remission in 62.8%; 17% patients had

died of renal causes [6].

The limitations of the present analysis are similar

to those of any retrospective report, including recall or reporting

bias. There was limited information on the time to first remission,

precise indications and duration of use of alternative agents, and on

morbidities that did not require hospitalization. Patients were referred

many months after the onset of symptoms and with a relatively difficult

illness, perhaps limiting the scope of these findings. However,

similarity of the disease course in patients who had presented at the

first episode suggests that these findings were valid and might be

generalized to patients with nephrotic syndrome in India.

The present study, on a large and recent group of

patients with steroid sensitive nephrotic syndrome, identifies the

course of the illness and existing therapeutic practices. It reconfirms

the importance of age at onset of nephrotic syndrome, the need for

adequate initial steroid therapy and duration of initial remission in

predicting the risk of frequent relapses. The outcomes were

satisfactory, and on follow up most patients were in sustained remission

or had infrequent relapses.

Contributors: RNS, AB and PH were responsible for

setting up the database. AS, PKS, AG, MM were involved in retrieval of

information from records and its analysis, MK provided statistical

inputs, and AKD reported all histological specimens. All authors

contributed to the preparation of the manuscript, provided significant

inputs during preparation for final publication and approved the final

manuscript. AB supervised the study and shall be its guarantor.

Funding: None; Competing interests: None

stated.

|

What Is Already Known?

• Frequent relapses are an important cause of

morbidity in children with steroid sensitive nephrotic syndrome.

• Risk factors for relapses are an early age

of onset, short initial therapy and delayed time to remission.

What This Study Adds?

• More than one-half of all patients with

steroid sensitive nephrotic syndrome show frequent relapses.

Risk factors include onset at <4 years of age, initial therapy

for less than 8 weeks, and brief initial remission lasting <6

months.

• Infections constitute the chief cause for

morbidity and mortality.

• The long-term outcome of nephrotic syndrome is satisfactory

in the majority.

|

References

1. Report of the International Study of Kidney

Disease in Children. Early identification of frequent relapsers among

children with minimal change nephrotic syndrome. A report of the

International Study of Kidney Disease in Children. J

Pediatr.1982;101:514-8

2. Bagga A, Mantan M. Nephrotic syndrome in children.

Indian J Med Res. 2005;122:13-28.

3. Tarshish P, Tobin JN, Bernstein J, Edelman CM.

Prognostic significance of the early course of minimal change nephrotic

syndrome: Report of the International Study of Kidney Disease in

Children. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8:769-76.

4. Fakhouri F, Bocquet N, Taupin P, Presne C,

Gagnadoux MF, Landais P, et al. Steroid-sensitive nephrotic

syndrome: From childhood to adulthood. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003; 41:550-7.

5. Koskimies O, Vilska J, Rapola J, Hallman N.

Long-term outcome of primary nephrotic syndrome. Arch Dis Child.

1982;57:544-8.

6. Wynn SR, Stickler GB, Burke EC. Long-term

prognosis for children with nephrotic syndrome. Clin Pediatr.

1988;27:63-8.

7. Hodson EM, Willis NS, Craig JC. Non-corticosteroid

treatment for nephrotic syndrome in children. Cochrane Database Syst

Rev. 2008;1: CD002290; DOI 10.1002/14651858.CD002290.pub3

8. Andersen RF, Thrane N, Noergaard K, Rytter L,

Jespersen B, Rittig S. Early age at debut is a predictor of

steroid-dependent and frequent relapsing nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr

Nephrol. 2010;25:1299-1304.

9. Letavernier B, Letavernier E, Leroy S, Baudet-Bonneville

V, Bensman A, Ulinski T. Prediction of high-degree steroid dependency in

pediatric idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol.

2008;23:2221-6.

10. Yap HK, Han EJS, Heng CK, Gong WK. Risk factors

for steroid dependency in children with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome.

Pediatr Nephrol. 2001;16:1049-52.

11. Constantinescu AR, Shah HB, Foote EF, Weiss LS.

Predicting first-year relapsers in children with nephrotic syndrome.

Pediatrics. 2000;105:492-5.

12. Srivastava RN, Mayekar G, Anand R, Choudhry VP,

Ghai OP, Tandon HD. Nephrotic syndrome in Indian children. Arch Dis

Child. 1975;50:626-30.

13. Indian Pediatric Nephrology Group, Indian Academy

of Pediatrics. Management of steroid sensitive nephrotic syndrome:

Revised guidelines. Indian Pediatr. 2008;45:203-14.

14. National High Blood Pressure Education Program

Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The

fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood

pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114:555-76.

15. Hamill PV, Drizd TA, Johnson CL, Reed RB, Roche

AF. NCHS growth curves for children birth -18 years. United States.

Vital Health Stat 11. 1977;165:1-74.

16. Bagga A, Hari P, Srivastava RN. Prolonged versus

standard prednisolone therapy for initial episode of nephrotic syndrome.

Pediatr Nephrol. 1999;13:824-7.

17. International Study of Kidney Disease in

Children. Primary nephrotic syndrome in children: clinical significance

of histopathologic variants of minimal change and of diffuse mesangial

hypercellularity. Kidney Int. 1981;20:765-71.

18. Kabuki N, Okugawa T, Hayakawa H, Tomizawa S,

Kasahara T, Uchiyama M. Influence of age at onset on the outcome of

steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 1998;12:467-70.

19. Fujinaga S, Hirano D, Nishizaki N. Early

identification of steroid dependency in Japanese children with

steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome undergoing short-term initial

steroid therapy. Pediatr Nephrol. 2011;26:485-6.

20. Bakkali LE, Pereira RR, Kuik DJ, Ket JCF, van

Wijk JAE. Nephrotic syndrome in The Netherlands: a population-based

cohort study and a review of the literature. Pediatr Nephrol.

2011;26:1241-6.

21. Srivastava RN, Agarwal RK, Moudgil A, Bhuyan UN.

Late resistance to corticosteroids in nephrotic syndrome. J Pediatr.

1986;108:66-70.

22. Gulati A, Sinha A, Sreeniwas V, Math A, Hari P,

Bagga A. Daily corticosteroids reduce infection associated relapses in

frequently relapsing nephrotic syndrome: a randomized controlled trial.

Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:63-9.

23. Ehrich JH, Brodehl J. Long versus standard

prednisone therapy for initial treatment of idiopathic nephrotic

syndrome in children. Arbeitsgemeinschaft fur Pädiatrische Nephrologie.

Eur J Pediatr. 1993;152:357-61.

24. Hodson EM, Knight JF, Willis NS, Craig JC.

Corticosteroid therapy for nephrotic syndrome in children. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev. 2005;1:CD001533

25. Takeda A, Matsutani H, Niimura F, Ohgushi H. Risk

factors for relapse in childhood nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol.

1996;10:740-1.

26. Abeyagunawardena AS, Dillon MJ, Rees L, van’t

Hoff W, Trompeter RS. The use of steroid-sparing agents in

steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2003;18:919-24.

27. Srivastava RN, Agarwal RK, Choudhry VP, Moudgil

A, Bhuyan UN, Sunderam KR. Cyclophosphamide therapy in frequently

relapsing nephrotic syndrome with and without steroid dependence. Int J

Pediatr Nephrol. 1985;6:245-50.

28. Bagga A, Sharma A, Srivastava RN. Levamisole

therapy in corticosteroid dependent nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol.

1997;11:415-7.

29. Bagga A, Hari P, Moudgil A, Jordan SC.

Mycophenolate mofetil and prednisolone therapy in children with

steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome. Am J Kid Dis. 2003;42:1114-20.

|

|

|

|

|