|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2013;50: 473-476

|

|

Effect of Second Dose of Measles Vaccine on

Measles Antibody Status:

A Randomized Controlled Trial

|

|

Anjum Fazilli, Abid Ali Mir, Rohul Jabeen Shah, Imtiyaz Ali

Bhat, *Bashir Ahmad Fomda and

†Mushtaq Ahmad Bhat

From the Departments of Community Medicine,

*Microbiology and †Pediatrics, Sher-i-Kashmir Institute of

Medical Sciences, Soura, Srinagar, J&K, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Mushtaq Ahmad Bhat,

Additional Professor Pediatrics, SKIMS, Srinagar, Kashmir,

India.

Email:

[email protected]

Received: July 12, 2012;

Initial review: September 20, 2012;

Accepted: October 25, 2012.

|

Objective: To evaluate the effect of the second dose of measles

vaccine on measles antibody status during childhood.

Setting: Immunization centre of Under-five Clinic

of the Department of Community Medicine at a tertiary-hospital.

Design: Randomized Controlled trial.

Methods: Blood samples were collected from all

subjects for baseline measles serology by heel puncture at 9-12 months

of age. All subjects were given the first dose of measels vaccine. At

second visit (3-5 months later), after collecting the blood sample from

all, half the children were randomized to receive the second dose of

measles vaccine (study group), followed by collection of the third

sample six weeks later in all the subjects.

Results: A total of 78 children were enrolled and

30 children in each group could be analyzed. 11(36.6%) children in the

study group and 13 (43.3%) children in the control group had protective

levels of measles IgG at baseline. Around 93.3 % of children in the

study group had protective measles antibody titers as against 50% in the

control group at the end of the trial. The Geometric Mean Titre (GMT) of

measles IgG increased from 14.8 NTU/mL to 18.2 NTU/mL from baseline to

six weeks following receipt of the second dose of the vaccine in the

study group, as compared to a decrease from 16.8 NTU/mL to 12.8 NTU/mL

in the control group.

Conclusions: A second dose of measles vaccine

boosts the measles antibody status in the study population as compared

to those who receive only a single dose.

Key words: Immunization, India, Measles, Prevention,

Second-dose, Serology.

|

|

Measles is a leading cause

of death among young children. Many experts now

recommend two doses of the measles vaccine to

ensure immunity, as about 15% of vaccinated

children fail to develop immunity from a single

dose [1]. In the past, there was a concern that

early immunization of infants who still have the

maternal antibody modified the immune response

such that the infant would not respond

adequately to a second dose. However, most

studies have shown that the overall proportion

of children who are seropositive after primary

immunization before 12 months of age and

re-immunized at age 15 months or later is at

least 95%, similar to that after initial

immunization at 15 months. Epidemiological data

support the efficacy of a second dose in the

presence of maternal antibody. Many countries

have initiated a two dose Measles, Mumps and

Rubella vaccine schedule with the aim of

eliminating Rubella and Measles [2]. The

rationale for the second dose has been to

protect those who did not seroconvert after the

first dose of measles vaccine. In an outbreak

investigation in USA, attack rates were 30-60%

lower in persons who received two doses of

measles vaccine as compared to those who

received one dose only [3].

In India, one dose of measles

vaccine is given under Universal Immunization

Program at 9 months of age. As some developing

countries have adopted a 2-dose schedule, Indian

Academy of Pediatrics has now recommended second

dose of measles vaccine at 15 months of age.

There is paucity of literature regarding the

effect of second dose of measles vaccination on

serological status in developing countries,

especially in the Indian subcontinent. Hence the

present study was designed to evaluate the

effect of second dose of measles vaccine on

measles antibody status during childhood.

Methods

This was a randomized

controlled trial conducted in the Under-five

Immunization Clinic of Department of Community

Medicine at Sher-i-Kashmir Institute of Medical

Sciences, Srinagar, Kashmir; a tertiary-care

hospital in northern India. The study was

conducted from May, 2008 to February, 2009. The

required sample size for the study was

calculated to be 30 in each arm [4]. A total of

78 subjects were enrolled in the study giving

allowance for the attrition factor. The study

was approved by the Ethical Committee of the

Institute.

Every alternate infant (age

9-12 months) reporting for measles vaccination

on the given day was enrolled in the study.

These infant were divided into two groups, one

designated as study group that received second

dose of measles vaccine 3-5 months after the

first dose at 9-12 months of age and the other

as control group receiving similar dose of

placebo (normal saline) after 1 st

dose of measles vaccine at 9-12 months of age.

Since measles vaccination is done only once in a

week, the average children vaccinated at the

immunization center on each week’s immunization

day was 20-25 and the process of enrollment of

the infants was completed in around eight

sessions.

Infants with a history of

measles, infants with a history of measles in

the family or immediate neighborhood during the

past one month, and infants whose age could not

be ascertained were excluded. Written consent

was obtained from the parents/guardians of

participants on a form that provided relevant

details of the study.

|

|

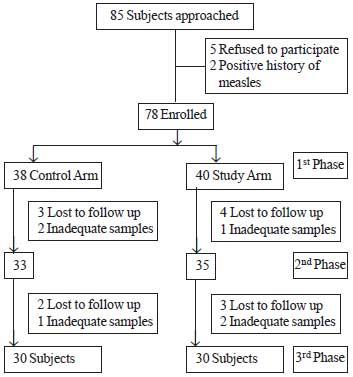

Flow chart showing

flow of infants in the study.

|

Pertinent information was

collected from the mother and entered into a

pre-designed proforma. The data information

related to demography, breastfeeding, weaning,

immunization and disease history. Subjects were

examined, their weight and height, head

circumference, and mid-upper arm circumference,

was measured. Weight was assessed using pan type

weighing scale. Height was measured using an

infantometer. Head circumference and Mid -arm

circumference was assessed using an inch tape.

Three blood samples were

collected from each patient and were processed

as per the manufacturer’s recommendations and

results were expressed in Nova Tech units [5,6].

Chi square test and Fisher test were used for

analysis.

Results

A total of 60 children were

enrolled in the study, 30 for the study group

and 30 for the control group. At enrollment, the

baseline variables of children in two groups

were comparable (Table I).

The proportion of children with protective

levels of measles IgG and the geometric mean

titers (GMT) of measles IgG were almost similar

in both groups at baseline. Measles IgG for

study group was similar between the two groups,

but it was significantly higher in the study

group at third visit (Table II).

TABLE I Demographic Details of The Study Population (N=60)

|

Study group |

Control group |

|

Females (%) |

8 (26) |

11 (36) |

|

Age |

|

|

|

First phase |

9.5 (0.73) |

9.53 (0.68) |

|

2nd phase |

13.8 (1.33) |

13.4 (1.24) |

|

Weight (kg) Mean ± SD |

|

|

|

First phase |

8.08 (1.01) |

8.14 (1.03) |

|

2nd phase |

9.74 (1.37) |

9.49 (1.11) |

|

Height (cm), Mean ± SD |

|

|

|

First phase |

68.9 (4.38) |

70.3 (4.92) |

|

2nd phase |

74.8 (5.16) |

74.5 (4.34) |

|

Literate mothers (%) |

9 (30) |

17 (56.6) |

|

Working mothers (%) |

1 (3.3) |

2 (6.7) |

TABLE II Measles IgG Titers in Studied Children During Three Phases of the Trial (N=60)

|

Study Group |

Control Group |

P |

|

n=30(%) |

n=30(%) |

value |

|

First phase |

|

|

|

|

No. with protected titers |

11(36.6) |

13 (43.3) |

0.792 |

|

GMT (NTU/mL)* |

10.60 |

11.21# |

|

|

Second phase |

|

|

|

|

No. with protected titers |

23 (76.6) |

21 (70.0) |

0.771 |

|

GMT (NTU/mL)* |

14.93 |

12.11 |

|

|

Third phase |

|

|

|

|

No. with protected titers |

28 (93.3) |

15 (50.0) |

0.0004 |

|

GMT (NTU/mL)* |

18.19 |

9.04 |

|

The GMT of measles IgG when

compared between protected and non-protected

children across two groups was higher for study

group than control group, both at the second and

third visit, though the difference was not

statically significant (Table III).

TABLE III Comparison Between GMJT of (NTU/mL) Measles IgG of the Study and Control Group

|

Study Group |

Control Group |

P |

|

n=30(%) |

n=30(%) |

value |

|

First phase |

|

Protected |

14.84 |

16.86 |

0.880 |

|

Not protected |

8.78 |

8.52 |

|

|

Second phase |

|

Protected |

16.91 |

13.12 |

0.643 |

|

Not protected |

9.38 |

8.36 |

|

|

Third phase |

|

Protected |

18.49 |

12.8 |

0.492 |

|

Not protected |

10.13 |

8.97 |

|

Discussion

The study found that a second

dose of measles vaccine boosts IgG levels

post-vaccination, as compared to children

receiving one dose approximately 3-5 months

earlier.

The choice of the serological

assay is important in evaluating the response to

immunization. Both Plaque Nutralization assays

and ELISA are more sensitive than the

Heamagglutination Inhibition assays [6]. At

present no serological test can differentiate

between antibodies (whether IgG or IgM) produced

by measles infection and that produced by

immunization. The levels of antibody induced by

immunization with attenuated measles virus vary

with an approximately log-normal distribution.

The proportion of children

having protective levels of measles IgG at 1 st

visit in this study was higher than 3.5%- 17.6%

reported in the literature [7-9]. The reason for

our observation could be a pre-vaccination

exposure to wild measles virus infection since

measles is highly endemic in this region.

At the third visit, which was

scheduled at six weeks following the receipt of

second dose of measles vaccine in study group

and a placebo in control group, a significantly

higher number of children had protective levels

of measles IgG in the study group. Similar

results (93.7% vs 84.7%, respectively)

have been reported from North Korea [10].

However, in our study, the proportion of

protected children in the control group

decreased from 70% to 50% from second to third

visit. The explanation for this observation

could be that since the proportion of children

who had protective levels of measles IgG

antibodies at base line was quite high (43.3%),

which could either have been due to maternal

antibodies or natural infection. Measles being

highly endemic in this region, thus the

proportion that could have responded to measles

vaccine was actually less and the group which

did not respond to measles vaccine at nine

months continued with the waning phenomenon.

The GMT of IgG rose by 14.2 %

from first visit to second visit and by 8.8 %

from second to third visit in the study group,

while it gradually decreased in the control

group. An attempt was made to compare the

nutritional status of the children and immune

status but a significant relation could not be

established.

Our study proves that second

dose of measles vaccine boosts the measles IgG

status in the study population as compared to

those who received only single dose. We also

observed that in the control group the

proportion of one dose vaccinated children

initially increased and then returned to almost

the same proportion protected at pre-vaccination

levels. This justifies the need for a second

dose of measles vaccine.

Contributors: All the

authors have designed and approved the

manuscript.

Funding: Research

Grant from Academic Section SKIMS; Competing

interests: None stated.

References

1. World Health Organization.

Measles. Available from:

www.who.int/mediacentre/fact sheet/fs286/en/.

Accessed on 2 October, 2012.

2. Measles –Immunological

basis for immunization /module 7: measles

WHO/EPI/GEN/93.7 Page-4. Accessed on 2 October,

2012.

3. Vitek CR, Aduddell

M, Brinton MJ, Hoffman RE, Redd SC. Increased

protections during a measles outbreak of

children previously vaccinated with a second

dose of measles-mumps-rubella vaccine. Pediatr

Infect Dis J. 1999;18:620-3.

4. Kirby A, Gebski V, Keech

AC. Determining the sample size in a clinical

trial. Med J Aust. 2002;177:256-7.

5. Riddell MA, Leydon JA,

Catton MG, Kelly HA. Detection of measles

virus-specific immunoglobulin M in dried venous

blood samples by using a commercial enzyme

immunoassay. J Clin Microbiol. 2002:40:5-9.

6. Nakano JH, Miller DL,

Foster SO, Brink EW. Microtiter determination of

measles haemagglutination inhibition antibody

with filter papers. J Clin Microbiol. 1983;17:

860-3.

7. Khalil MK, Nadrah HM, Al-Yahya

OA, Al-Saigul AM. Sero-response to measles

vaccination at 12 months of age in Saudi infants

in Qassim province. Saudi Med J.

2008;29:1009-13.

8. Mandomando IM, Naniche D,

Pasetti MF, Vallies X, Cuberos L, Nhacola A,

et al. Measles specific neutralizing

antibodies in rural Mozambique: sero-prevalence

and presence in breast milk. Am J Trop Med

Hyg.2008; 79: 787-92.

9. Jani JV, Holm-Hansen C,

Mussa T, Zaqngo A, Manhica I, Bjune G, et al.

Assessment of measles immunity among infants in

Maputo city, Mozambique. BMC Public

Health. 2008;8:386.

10. Bae GR, Lim HS, Goh UY,

Yang BG, Kim YT, Lee JK. Seroprevelence of

measles antibody and its attributable factor in

elementary students of routine 2- dose schedule

era with vaccination record. J Prev Med Public

Health. 2005;38:431-6.

|

|

|

|

|