Anti-myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibody disease has been

recently implicated as a major etiology for pediatric non-infectious

encephalitis [1]. We report a case of acute fulminant encephalitis in a

5 year old child mimicking viral encephalitis, which was eventually

diagnosed as anti-MOG antibody encephalitis leading to successful

treatment with immunotherapy, thus highlighting this condition as an

important differential diagnosis for acute viral encephalitis.

A 5-years-old previously normal Indian girl presented

with intermittent fever for 4 days, headache for 2 days followed by

encephalopathy. On admission, she was afebrile with normal vital signs

and a Glasgow coma scale of 12. Subsequently her GCS deteriorated to 8

within 12 hours necessitating mechanical ventilation, and she developed

signs of raised moderate intracranial hypertension and relative

bradycardia. Neuro-logical examination showed sluggish brainstem

reflexes including pupillary and occulocephalic reflex, brisk deep

tendon reflexes and bilateral extensor plantar response. There was no

history of seizures, abnormal movements, visual disturbances, bowel or

bladder dysfunction, or preceding altered sleep or behavior. There was

no history of contact with tuberculosis or recent travel. There was no

history of drug ingestion or any toxic exposure. The initial working

diagnosis was acute febrile encephalopathy with differential diagnosis

of viral encephalitis, acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis (ADEM) or

neuro-metabolic disease with acute decompen-sation. Emergent

neuroprotection measures and a combination of broad spectrum

antimicrobials including Acyclovir were instituted.

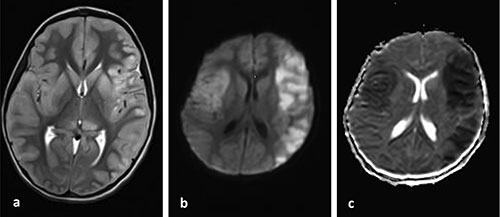

MRI brain showed extensive asymmetrical high signal

changes involving bilateral cortical regions along with ventromedial

thalamus with extensive diffusion restriction suggestive of cytotoxic

edema (Fig. 1). Post contrast study showed no evidence of

parenchymal or leptomeningeal enhancement. MRI of spine and MR angiogram

were normal. On day 2 of admission, patient developed focal seizures

with EEG showing bilateral periodic lateralizing epileptiform discharges

(PLEDs) highly suggestive of a neurotropic viral encephalitis. Due to

the patientís clinical condition, cere-brospinal fluid (CSF) was

deferred until the second week and was unremarkable including negative

routine studies, culture and PCR for neurotropic viruses. The patient

remained deeply encephalopathic and ventilator dependent for the next

two weeks with no response to treatment including acyclovir. In the

second week of admission she developed stereotypical flinging repetitive

asymmetrical lower limb movements, prompting a trial of methyl

prednisolone and immunoglobulins alongside autoimmune and lupus workup

including CSF and serum anti-NMDAR (N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor)

antibodies and oligoclonal bands which were negative. However, there was

no significant clinical improvement. This led to the counselling of the

family regarding an acute fulminant encephalitis with poor neurological

outcome and need for tracheostomy. After review of the recently

published case series by Armangue, et al. [1], serum anti-MOG antibodies

(IgG) immunofluorescence test was sent and showed a positive titer of

1:40. Plasma Exchange was then instituted with a total of 5 cycles on

alternate days. After the second cycle of plasma exchange itself, the

patient showed rapid clinical improvement in the form of improved GCS

and was successfully weaned off from ventilation. At the time of

discharge two weeks later, the patient could walk unsupported and talk

in simple sentences. On follow-up at 4 months after the illness, the

patient remained clinically well, and had regained pre-illness

developmental status. Her repeat anti-MOG titers were negative and

repeat neuroimaging showed no active lesions.

|

|

Fig. 1 a) MRI T2-weighted image showing

bilateral asymmetrical (left more than right) cortical high

intensity signal with cortical swelling along with high signal

in the ventromedial thalami, b) MRI diffusion weighted image

(DWI) and c) apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) images showing

bilateral cortical cytotoxic edema in the form of diffusion

restriction and corresponding drop in the ADC values.

|

During the last decade, anti-MOG antibodies have been

implicated in a wide range of pediatric acquired demyelinating syndromes

including optic neuritis, myelitis and ADEM [2]. However a recent

multicenter observational study by Armangue, et al highlighted the

widening spectrum of anti-MOG antibodies disease [1], demonstrating it

as the commonest etiology of non-infectious, non-ADEM encephalitis in

the pediatric age group, in addition to the well-established

presentations mentioned above. Of the 116 anti-MOG antibody positive

patients recruited in the study, 22 (19%) were diagnosed as encephalitis

other than ADEM, thus making it an important differential diagnosis in

pediatric encephalitis. The clinical presentation included

encephalopathy, seizures, status epilepticus, fever, abnormal behavior,

motor deficits, abnormal movements and brainstem-cerebellar dysfunction.

MRI showed non-ADEM like findings including extensive bilateral cortical

involvement (55%) with or without basal ganglia involvement and

meningeal enhancement. Another recent publication by Budhram, et al.

coined the term FLAMES based on a distinct radiological pattern of

unilateral cortical FLAIR-hyperintense lesions in adult anti-MOG

encephalitis with seizures [3]. Our case had clinical features of

encephalopathy, brainstem dysfunction and abnormal movements while MRI

brain showed extensive bilateral cortical and basal ganglia involvement

with diffusion restriction but without meningeal enhancement. These

observations were in keeping with the findings described in the study by

Armangue, et al. [1]

We conclude that anti-MOG encephalitis should be

considered in a child with fulminant encephalitis with bilateral

cortical involvement with diffusion restriction on MRI, with or without

meningeal contrast enhancement. Steroids should be the first line

treatment for anti-MOG encephalitis, and usually shows a good response.

However, early plasma exchange should be considered in cases with

inadequate response to pulse steroids.

1. Armangue T, Olive-Cirera G, Martinez-Hernandez E,

et al. Associations of paediatric demyelinating and encephalitic

syndromes with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies: A

multicentre observational study. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19:234-46.

2. Fernandez-Carbonell C, Vargas-Lowy D, Musallam A,

et al. Clinical and MRI phenotype of children with MOG antibodies. Mult

Scler. 2016;22:174-84.

3. Budhram A, Mirian A, Le C, et al. Unilateral

cortical FLAIR-hyperintense lesions in Anti-MOG-associated Encephalitis

with Seizures (FLAMES): Characterization of a distinct clinico-radiographic

syndrome. J Neurol. 2019; 266:2481-87.