|

Infantile hemangiomas (IH)

are the most common infantile tumor, with a

frequency of 4-10% [1]. Recently, there has been

an interest in propranolol and other

beta-blockers in the treatment of IH.

Propranolol may be more effective and safer than

previously established therapies, and may be an

alternative when more widely accepted treatments

for IH have failed. Initial studies suggest that

it may also be used as a first-line therapy.

Other selection criteria may include lesion

location that is inaccessible to surgery,

lesions with a deep component, severe ulceration

and/or cosmetic disfigurement, obstruction of

airway or visual axis, and the presence of

contraindications to other medical therapies.

Parental apprehension remains an important

indication for treatment in cutaneous IH,

irrespective of the possibility of spontaneous

involution. In this review, the authors

summarize the existing literature concerning

propranolol use in IH treatment and provide

suggestions for its clinical use and for future

areas of study.

Natural History

IH are benign tumors of the

vascular endothelium. The first sign of IH is

characteristically an area of pallor that

appears several days after birth. The

proliferative phase of hemangioma development is

characterized by excessive angiogenesis and

occurs over three to six months, whereas the

involutional phase occurs over several years.

Although complete involution occurs over months

to years [1], IH may remain unresolved. Up to

40% of lesions result in textural changes and

fibrofatty scarring [2].

Diagnosis

A vascular lesion that

follows the pattern described is taken to be IH

until proven otherwise [2]. If a lesion does not

follow the established pattern, diagnosis can be

supported by Doppler ultrasound, magnetic

resonance imaging (MRI) or angiography [1].

Locations and Complications

Cutaneous IH can be

cosmetically disfiguring and may cause parental

apprehension. About 5-13% of cutaneous IH

ulcerate [1], which may lead to pain, bleeding

and scarring. Glottic IH can extend to the

supra-glottic and sub-glottic regions and can

partially occlude the airway [3]. Periorbital IH

may lead to vision deprivation, astigmatism and

strabismus [4]. Involvement of the ear canals

may impede hearing. IH involving the viscera or

central nervous system may be complicated by

hemorrhage, thrombocytopenia, anemia,

disseminated intravascular coagulation and

congestive cardiac failure, a constellation of

symptoms collectively described as

Kasabach-Meritt syndrome. Extensive IH may occur

in PHACE syndrome (posterior fossa

malformations, hemangiomas, arterial lesions,

coarctation of the aorta and other cardiac

defects, and eye abnormalities) [1].

Pathophysiology

IH are clonal expansions of

endothelial cells. Genetic mutations in

angiogenesis-related protein expression have

been identified [5]. Characteristic features of

IH include elevated expression of alkaline

phosphatase, factor VIII antigen, and cluster of

differentiation 31. Elevated expression of pro-angiogenic

factors, such as vascular endothelial growth

factor (VEGF), basal fibroblast growth factor

and proliferating cell nuclear antigen may

stimulate endothelial growth and lead to

dysregulated angiogenesis [6]. The

overexpression of glucose transporter 1 (GLUT-1)

is specific to IH and is not found in other

vascular tumors [7].

IH Treatment Patterns and

Modalities

Treatment for IH may be

necessary to a) prevent or improve functional

impairment or pain, b) prevent or improve

scarring or disfigurement, and c) avoid

life-threatening complications. Accepted

treatments include intralesional and systemic

corticosteroids, chemotherapy (vincristine and

interferon alpha), liquid nitrogen cryotherapy,

laser ablation and surgical excision [1].

Corticosteroids are currently the preferred

therapy for most types of IH.

Recent interest in the use of

propranolol in the treatment of IH followed a

2008 report by Ležautež-LabreŐze following an

incidental finding [8]. Following several

corroborative reports, propranolol therapy was

further investigated in a twenty-patient

randomized control trial (RCT) [9].

Mechanism of Action

Several mechanisms of action

for propranolol have been suggested. Results

from combined grayscale and color Doppler

ultrasound imaging suggest that propranolol

reduces vessel density [10]. Propranolol has a

dose-dependent cytotoxic effect on cultured

hemangioma endothelial cells via the

hypoxia-inducible factor 1Š pathway, leading to

decreased secretion of VEGF [11]. In vitro

propranolol decreases plasmalemmal expression of

GLUT-1 [12], though no study has evaluated this

hypothesis to date with respect to IH. Other

possible mechanisms of action include inhibition

of matrix metalloproteinases, down-regulation of

interleukin-6 and modulation of stem-cell

differentiation [11].

Methods

We conducted a search on

PubMed using combinations of search terms "propranolol",

"hemangioma", "beta-blocker," and

"beta-antagonist." All relevant publications

from 2009-2012 in all languages were reviewed.

Bibliographies of relevant articles were

investigated. We reported trial methodology,

dosing and investigations, IH localizations,

follow-up data, and adverse effects from RCTs,

case series, and case reports. Levels of

evidence were determined using Oxford criteria

(www.cebm.org). In table I, level 3 studies and

higher were universally included, and level 4

studies were included if n

≥30.

Studies were assessed for bias.

Results

A number of studies have

evaluated propranolol in IH (Table I).

Most investigators did not specify during which

phase the treatment took place, though one

investigator examined the efficacy of

propranolol after the proliferative phase [14].

A few investigators included patients previously

treated with steroids [4,8,15-19]. Patients with

bronchial asthma were generally excluded. Most

investigators increased drug dose to the target

over days to weeks [3,9,18,20-24], while others

initiated treatment at the target dose [13,15,

25-27]. Some studies used quantitative scores

and/or serial photography to assess IH

regression [9,13,15, 23, 25, 28]. Treatment was

discontinued following either regression or

complete resolution. A few investigators

followed dose-tapering protocols [3,9,25].

Follow-up was done after treatment

discontinuation to monitor for rebound growth.

To summarize the information presented in table

I, dosages of propranolol ranged from 1.0-3.0

mg/kg/day and the duration of treatment ranged

from 1-14 months, the mean duration being 5.85

months. Mean age at treatment was 12.7 months.

|

|

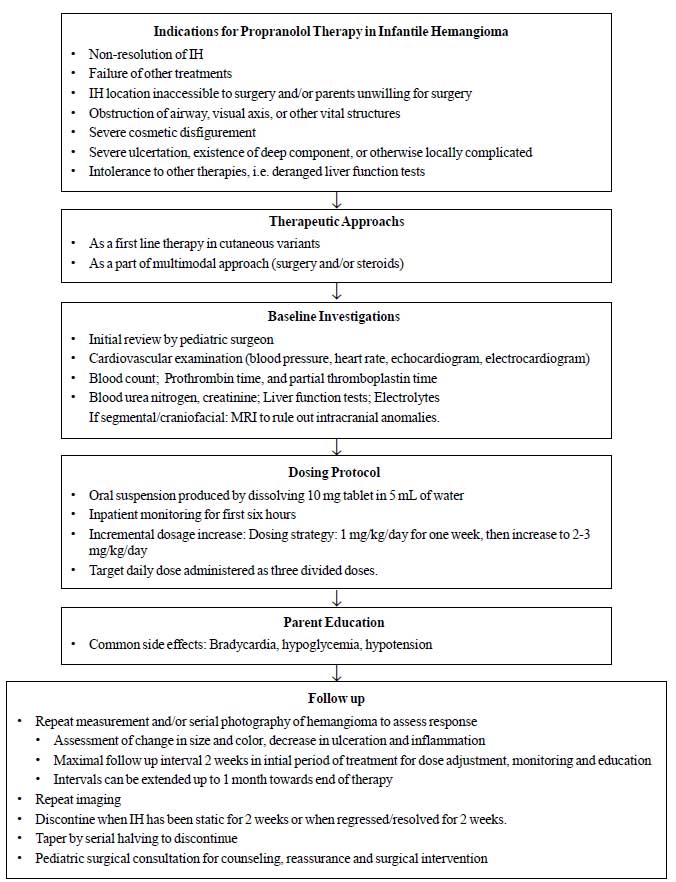

Fig.1 Suggested

management approach to infantile

hemangioma.

|

Outcomes

A summary of the larger

studies in the literature is provided in

Web Table I.

Cutaneous hemangiomas.

Indications for treatment include extensive

ulceration, presence of deep component, and

cosmetic disfigurement (Fig.1).

Propranolol reduces color intensity, size and

thickness of IH. IH may improve as early as 4

weeks after treatment initiation [15].

Propranolol has been reported to resolve

ulcerated IH [18, 26]. Propranolol has been

documented to resolve IH resistant to steroid

treatment [4,8,15-19].

Hepatic hemangioma.

Propranolol has been documented to resolve

hepatic IH [16]. Therapy can be initiated when

steroids are contraindicated, using an

incremental dose increase and close MRI

monitoring. Periodic ultrasonography can also

document tumor regression [19]. Propranolol in

hepatic IH has been used as late as 10 months

after birth [29].

Orbital hemangioma.

Propranolol treatment is efficacious in the

majority of orbital IH [4], occasionally leading

to resolution of proptosis and reduction of

astigmatism and amblyopia [4,30].

Subglottic hemangioma.

Favorable reports in laryngeal IH have been

published [17, 31]. Periodic laryngoscopy is

required to monitor tumor regression.

Other hemangiomas.

Propranolol has successfully resolved

retroperitoneal [32] and mediastinal [33]

hemangiomas. In reported outcomes in children

with PHACE syndrome, propranolol caused

significant yet incomplete reduction of IH

[3,34-37]. The response to propranolol is

maximal in the first 20 weeks of treatment and

may subside after this [36]. Imaging of cerebral

blood vessels should be undertaken before

treatment to determine the risk of cerebral

ischemia [3].

Limitations. Complete

treatment failure has been documented [3,31]. IH

may undergo rebound growth following cessation

of treatment [8,38].

Adverse Effects

Adverse effects include

hypoglycemia, bradycardia, hypotension, and

airway hyperreactivity. In an RCT, bradycardia

and hypotension were the most common adverse

effects [9]. Hypoglycemia may occur secondary to

inhibited glycogenolysis, glycolysis and

lipolysis [39]. A list of side effects

attributed to propranolol use in infants is

provided in Box I.

Box I Adverse Effects

Associated with Nonselective Beta-Blocker

Therapy

|

Metabolic

Hypoglycemia [22,

39]

Cardiac

Bradycardia [15, 20,

49]

Hypotension [13, 20,

21, 28]

Tachycardia [22]

Central Nervous System

Agitated sleep [9,

15, 18, 21, 26, 28, 30, 49]

Insomnia [13]

Drowsiness [18, 23,

24, 30, 38]

Crying

episodes/Anxiety [30]

Hypotonia [23]

|

Pulmonary

Wheezing [13, 20,

24]

Stridor [15]

RSV exacerbation [9,

50]

Gastrointestinal

Diarrhea/GI upset

[18, 28, 34, 49]

Gastroesophageal reflux [21, 24, 26,

34]

Other

Cold palms [13, 24,

26]

Night sweats [13]

Skin changes [22,

24, 50]

|

Preterm infants

Propranolol was reported to

be effective in a series comprised of seven

preterm infants. No side effects, including

changes in heart rate or blood pressure, were

reported in this group [40]. Similar findings

were reported in a series that included six

preterm infants [41]. Another published report

evaluated propranolol use in 16 very-low birth

weight children, of whom nine were born between

27-34 weeks of gestation. Two infants in these

series had a fall in blood pressure within the

first six hours of therapy, though this was

within physiological limits [42].

Other beta-blockers

Acebutolol, nadolol and

timolol may provide similar efficacy to

propranolol in IH treatment. Acebutolol has been

used in treatment of subglottic IH [31]. Topical

timolol has been effective for cutaneous [20]

and ocular [43] IH. Cardioselective

beta-blockers may be safer and easier to

administer than propranolol.

Combined propranolol and

corticosteroids

In complicated IH,

propranolol may be used in combination with

corticosteroids for a more rapid response. In

one report, a 3-month-old child with a

superficial IH obscuring the visual axis was

treated with combined propranolol and

prednisolone, the latter being gradually

withdrawn over one month [44]. In another

report, two children with airway-obstructing IH

were treated with combined prednisolone and

propranolol. After 24 hours, both children were

relieved of stridor and steroid was discontinued

[45]. These reports suggest that the use of

combination propranolol and corticosteroid

therapy may provide a valid therapeutic approach

to otherwise difficult-to-treat IH.

Propranolol and surgery

Propranolol may limit the

need for surgery in IH. In a multicenter study

comparing propranolol to corticosteroid

treatment for IH, 12% of children treated with

propranolol required surgery, whereas 29% of

those treated with steroids required surgery

[22]. Surgery still serves a role in IH that are

refractory to treatment or that need urgent

treatment [35]. Presumably, in patients with an

incomplete response to propranolol, medical

therapy may limit the extent of surgery

necessary for an easy and cosmetically

acceptable excision.

Route of administration

The route of administration

of propranolol in the majority of published

studies is via oral ingestion. Propranolol is

available in 10mg and 40mg tablets which can be

dissolved in water for easy administration.

Parents should be advised to soak the tablets in

10ml of water for one minute before crushing and

not to filter the suspension [46].

Intralesional drug injection

also causes regression of periorbital IH [47].

The use of a 1% ointment applied for cutaneous

IH led to regression in 85% of patients in a

case series [40]. Topical treatments may result

in fewer adverse effects.

Limitations

Most reviewed studies

provided level 4 evidence. They may be subject

to selection bias. Many of the studies did not

use objective measurement methodologies to

evaluate the efficacy of treatment.

Recommendations

We have suggested a tentative

treatment regimen (Fig.1). The

choice between in-hospital and outpatient

treatment should be made on a case-by-case basis

[48]. The childís age, history of prematurity,

hemangioma subtype and location, comorbidities,

and the level of parental understanding should

be considered. Abdominal ultrasonogram should be

obtained for visceral IH to check for hepatic

artery and portal vein dilatation. Patients with

PHACE syndrome should undergo cerebral

angiography to rule out cerebral ischemia.

Parental education should include discussion of

the warning signs of hypoglycemia and should

emphasize the importance of maintaining a

regular feeding schedule. A pediatric surgical

opinion should be sought, and parents should be

informed of the possibility of surgical excision

if therapy fails. In addition, downgraded IH or

fibrofatty remnants can be excised more

effectively following propranolol therapy.

Special consideration should be made for

premature infants, unusual or high-risk

locations, and patients with Kasabach-Merritt

syndrome. Regression of IH should be monitored

by serial photography. The above protocol should

be evaluated by randomized, large-scale trials.

Conclusion

Case reports have documented

the successful use of propranolol in the Indian

setting [19, 37]. Considering the challenges of

assuring patient compliance and maintaining

close follow-up in India, it is inadvisable to

promote propranolol therapy except in cases

where careful and close monitoring of patient

parameters is feasible.

Propranolol can be tried as

first-line therapy in IH irrespective of age,

location, extent and phase of growth. Treatment

might also be helpful in downgrading the size

and local complications of IH, making the lesion

more amenable to surgical excision. Due to the

lack of long-term side effects and its high

response rate, propranolol therapy may prove to

be superior to existing therapies. More

extensive prospective double-blinded RCT of

propranolol therapy must be carried out and

reported by pediatricians and pediatric surgeons

in order to establish its efficacy conclusively.

Contributors: NG:

designed and conceptualized the study, analyzed

and interpreted the data in the study, and

drafted the manuscript. SR: conceptualized the

study, drafted and revised the manuscript. SB:

conceptualized the study and interpreted the

data. JXS: conceptualized the study, interpreted

the data in the study and revised the

manuscript. All authors gave final approval of

the version to be published.

Funding: None;

Competing interests: None stated.

References

1. Frieden IJ, Haggstrom AN,

Drolet BA, Mancini AJ, Friedlander SF, Boon L,

et al. Infantile hemangiomas: current

knowledge, future directions. Proceedings of a

Research Workshop on Infantile Hemangiomas; 2005

April 7-9; Bethesda, Maryland, USA. Hoboken:

Wiley-Blackwell; 2005.

2. Young AZ, Cohen BA,

Siegfried EC. Cutaneous Congenital Defects.

In: Taeusch HW, Ballard RA, Gleason CA,

Avery ME, editors. Averyís diseases of the

newborn. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier

Saunders; 2005. p. 1521-38.

3. Manunza F, Syed S, Laguda

B, Linward J, Kennedy H, Gholam K, et al.

Propranolol for complicated infantile

haemangiomas: a case series of 30 infants. Br J

Dermatol. 2010;162:466-8.

4. Cheng JF, Gole GA,

Sullivan TJ. Propranolol in the management of

periorbital infantile haemangioma. Clin

Experiment Ophthalmol. 2010;38:547-53.

5. Yu Y, Varughese J, Brown

LF, Mulliken JB, Bischoff J. Increased Tie2

expression, enhanced response to angiopoietin-1,

and dysregulated angiopoietin-2 expression in

hemangioma-derived endothelial cells. Am J

Pathol. 2001;159:2271-80.

6. Takahashi K, Mulliken JB,

Kozakewich HP, Rogers RA, Folkman J, Ezekowitz

RA. Cellular markers that distinguish the phases

of hemangioma during infancy and childhood. J

Clin Invest. 1994;93:2357-64.

7. North PE, Waner M,

Mizeracki A, Mihm MC, Jr. GLUT1: a newly

discovered immunohistochemical marker for

juvenile hemangiomas. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:11-22.

8. Leaute-Labreze C, Dumas de

la Roque E, Hubiche T, Boralevi F, Thambo JB,

Taieb A. Propranolol for severe hemangiomas of

infancy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358: 2649-51.

9. Hogeling M, Adams S,

Wargon O. A randomized controlled trial of

propranolol for infantile hemangiomas.

Pediatrics. 2011;128:e259-66.

10. Bingham MM, Saltzman B,

Vo NJ, Perkins JA. Propranolol reduces infantile

hemangioma volume and vessel density.

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;147:338-44.

11. Greenberger S, Bischoff

J. Infantile Hemangioma-Mechanism(s) of Drug

Action on a Vascular Tumor. Cold Spring Harb

Perspect Med. 2011;1:a006460.

12. Egert S, Nguyen N,

Schwaiger M. Contribution of alpha-adrenergic

and beta-adrenergic stimulation to

ischemia-induced glucose transporter (GLUT) 4

and GLUT1 translocation in the isolated perfused

rat heart. Circ Res. 1999;84:1407-15.

13. Sans V, de la Roque ED,

Berge J, Grenier N, Boralevi F,

Mazereeuw-Hautier J, et al. Propranolol

for severe infantile hemangiomas: follow-up

report. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e423-31.

14. Zvulunov A, McCuaig C,

Frieden IJ, Mancini AJ, Puttgen KB, Dohil M,

et al. Oral propranolol therapy for

infantile hemangiomas beyond the proliferation

phase: a multicenter retrospective study.

Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:94-8.

15. Bagazgoitia L, Torrelo A,

Gutierrez JC, Hernandez-Martin A, Luna P,

Gutierrez M, et al. Propranolol for

infantile hemangiomas. Pediatr Dermatol.

2011;28:108-14.

16. Marsciani A, Pericoli R,

Alaggio R, Brisigotti M, Vergine G. Massive

response of severe infantile hepatic hemangioma

to propanolol. Pediatr Blood Cancer.

2010;54:176.

17. Mistry N, Tzifa K. Use of

propranolol to treat multicentric airway

haemangioma. J Laryngol Otol. 2010;124:1329-32.

18. Hermans DJ, van Beynum

IM, Schultze Kool LJ, van de Kerkhof PC, Wijnen

MH, van der Vleuten CJ. Propranolol, a very

promising treatment for ulceration in infantile

hemangiomas: a study of 20 cases with matched

historical controls. J Am Acad Dermatol.

2011;64:833-8.

19. Muthamilselvan S, Vinoth

PN, Vilvanathan V, Ninan B, Amboiram P, Sai V,

et al. Hepatic haemangioma of infancy:

role of propranolol. Ann Trop Paediatr.

2010;30:335-8.

20. Blatt J, Morrell DS, Buck

S, Zdanski C, Gold S, Stavas J, et al.

beta-blockers for infantile hemangiomas: a

single-institution experience. Clin Pediatr (Phila).

2011;50:757-63.

21. Holmes WJ, Mishra A,

Gorst C, Liew SH. Propranolol as first-line

treatment for rapidly proliferating infantile

haemangiomas. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg.

2011;64:445-51.

22. Price CJ, Lattouf C, Baum

B, McLeod M, Schachner LA, Duarte AM, et al.

Propranolol vs corticosteroids for infantile

hemangiomas: a multicenter retrospective

analysis. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1371-6.

23. Rossler J, Schill T, Bahr

A, Truckenmuller W, Noellke P, Niemeyer CM.

Propranolol for proliferating infantile

haemangioma is superior to corticosteroid

therapy - a retrospective, single centre study.

J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1173-5.

24. Schupp CJ, Kleber JB,

Gunther P, Holland-Cunz S. Propranolol therapy

in 55 infants with infantile hemangioma: dosage,

duration, adverse effects, and outcome. Pediatr

Dermatol. 2011;28:640-4.

25. Celik A, Tiryaki S,

Musayev A, Kismali E, Levent E, Ergun O.

Propranolol as the first-line therapy for

infantile hemangiomas: preliminary results of

two centers. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:808-11.

26. Saint-Jean M,

Leaute-Labreze C, Mazereeuw-Hautier J, Bodak N,

Hamel-Teillac D, Kupfer-Bessaguet I, et al.

Propranolol for treatment of ulcerated infantile

hemangiomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:827-32.

27. Talaat AA, Elbasiouny MS,

Elgendy DS, Elwakil TF. Propranolol treatment of

infantile hemangioma: clinical and radiologic

evaluations. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47:707-14.

28. Bertrand J, McCuaig C,

Dubois J, Hatami A, Ondrejchak S, Powell J.

Propranolol versus prednisone in the treatment

of infantile hemangiomas: a retrospective

comparative study. Pediatr Dermatol.

2011;28:649-54.

29. Mazereeuw-Hautier J,

Hoeger PH, Benlahrech S, Ammour A, Broue P, Vial

J, et al. Efficacy of propranolol in

hepatic infantile hemangiomas with diffuse

neonatal hemangiomatosis. J Pediatr.

2010;157:340-2.

30. Schiestl C, Neuhaus K,

Zoller S, Subotic U, Forster-Kuebler I, Michels

R, et al. Efficacy and safety of

propranolol as first-line treatment for

infantile hemangiomas. Eur J Pediatr.

2011;170:493-501.

31. Blanchet C, Nicollas R,

Bigorre M, Amedro P, Mondain M. Management of

infantile subglottic hemangioma: acebutolol or

propranolol? Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol.

2010;74:959-61.

32. Vanlander A, Decaluwe W,

Vandelanotte M, Van Geet C, Cornette L.

Propranolol as a novel treatment for congenital

visceral haemangioma. Neonatology.

2010;98:229-31.

33. Fulkerson DH, Agim NG,

Al-Shamy G, Metry DW, Izaddoost SA, Jea A.

Emergent medical and surgical management of

mediastinal infantile hemangioma with

symptomatic spinal cord compression: case report

and literature review. Childs Nerv Syst.

2010;26:1799-805.

34. Haider KM, Plager DA,

Neely DE, Eikenberry J, Haggstrom A. Outpatient

treatment of periocular infantile hemangiomas

with oral propranolol. J AAPOS. 2010;14:251-6.

35. Leboulanger N, Cox A,

Garabedian EN, Denoyelle F. Infantile

haemangioma and beta-blockers in otolaryngology.

Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis.

2011;128:236-40.

36. Hernandez-Martin S,

Lopez-Gutierrez JC, Lopez-Fernandez S, Ramirez

M, Miguel M, Coya J, et al. Brain

Perfusion SPECT in Patients with PHACES Syndrome

Under Propranolol Treatment. Eur J Pediatr Surg.

2011.

37. Mohanan S, Besra L,

Chandrashekar L, Thappa DM. Excellent response

of infantile hemangioma associated with PHACES

syndrome to propranolol. Indian J Dermatol

Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:114-5.

38. Chai Q, Chen WL, Huang

ZQ, Zhang DM, Fan S, Wang L. Preliminary

Experiences in Treating Infantile Hemangioma

With Propranolol. Ann Plast Surg. 2011.

39. Holland KE, Frieden IJ,

Frommelt PC, Mancini AJ, Wyatt D, Drolet BA.

Hypoglycemia in children taking propranolol for

the treatment of infantile hemangioma. Arch

Dermatol. 2010;146:775-8.

40. Kunzi-Rapp K. Topical

propranolol therapy for infantile hemangiomas.

Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:154-9.

41. Moehrle M, Leaute-Labreze

C, Schmidt V, Rocken M, Poets CF, Goelz R.

Topical Timolol for Small Hemangiomas of

Infancy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012.

42. Erbay A, Sarialioglu F,

Malbora B, Yildirim SV, Varan B, Tarcan A, et

al. Propranolol for infantile hemangiomas: a

preliminary report on efficacy and safety in

very low birth weight infants. Turk J Pediatr.

2010;52:450-6.

43. Ye XX, Jin YB, Lin XX, Ma

G, Chen XD, Qiu YJ, et al. [Topical timolol in

the treatment of periocular superficial

infantile hemangiomas: a prospective study].

Zhonghua Zheng Xing Wai Ke Za Zhi.

2012;28:161-4.

44. Koay AC, Choo MM, Nathan

AM, Omar A, Lim CT. Combined low-dose oral

propranolol and oral prednisolone as first-line

treatment in periocular infantile hemangiomas. J

Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2011;27:309-11.

45. Rosbe KW, Suh KY, Meyer

AK, Maguiness SM, Frieden IJ. Propranolol in the

management of airway infantile hemangiomas. Arch

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;136:658-65.

46. Nunn A, Shah U, Ford J.

Giving propranolol tablets to infants with

hemangiomas. J Paediatr Child Health.

2011;47:927.

47. Awadein A, Fakhry MA.

Evaluation of intralesional propranolol for

periocular capillary hemangioma. Clin Ophthalmol.

2011;5:1135-40.

48. Lawley LP, Siegfried E,

Todd JL. Propranolol treatment for hemangioma of

infancy: risks and recommendations. Pediatr

Dermatol. 2009;26:610-4.

49. Qin ZP, Liu XJ, Li KL,

Zhou Q, Yang XJ, Zheng JW. [Treatment of

infantile hemangiomas with low-dose propranolol:

evaluation of short-term efficacy and safety].

Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2009;89:3130-4.

50. Buckmiller LM, Munson PD,

Dyamenahalli U, Dai Y, Richter GT. Propranolol

for infantile hemangiomas: early experience at a

tertiary vascular anomalies center.

Laryngoscope. 2010;120:676-81.

|