The controversy about what fluids to use in critically

ill children to prevent hyponatraemia is ongoing. We congratulate Singhi

and Jayashree for their contribution to this debate(1). There is however

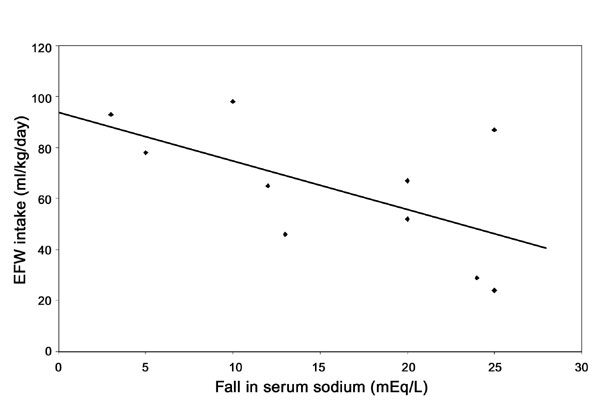

one point in their paper that needs clarification. In Fig.1,

a line showing electrolyte free water (EFW) intake and expected fall in

serum sodium has been drawn. It runs diagonally across the figure

suggesting that a linear relationship between the two is expected. The

data source for this assumption has not been provided.

|

|

Fig.1 Electrolyte free water (EFW) and fall

in sodium. |

Interestingly, in their data on children who developed

hyponatraemia, the biggest falls in serum sodium were seen in the patients

who received less EFW (r = – 0.57). The message can be best

conveyed by drawing the regression line. We have scanned in their figure

and have drawn the regression line in the attached figure. This graph

depicts data on the relationship of EFW and fall in sodium in patients who

developed hyponatraemia. It will be crucial to know whether this trend is

seen in the other patients also (those who did not develop significant

hyponatraemia), to test the hypothesis that fall in sodium is inversely

related to EFW. It may be possible to understand whether the group that

developed hyponatraemia is different from those who did not develop

hyponatraemia and we can then ‘focus on the inherent properties of the

patient’s physiology, rather than the inherent properties of the fluid

being used’ as suggested by Choong in the accompanying editorial(2).

References

1. Singhi S, Jayashree M. Free water excess is not the

main cause for hyponatremia in critically ill children receiving

conventional maintenance fluids. Indian Pediatr 2009; 46: 577–583.

2. Choong K. Should we add more salt, or less water. Indian Pediatr

2009; 46: 573-574.