The non-medical use of chemical substances in

order to achieve alterations in psychological functioning has been

termed as substance use(1). WHO estimates that globally, 25% to 90%

of street children indulge in substance use(2). According to UNICEF,

there are more than 5,00,000 street children in India(3) who live

and work in inhuman conditions(4) and are at high risk of substance

use(4-6). Knowledge of extent of the problem and socio-demographic

risk factors is essential to devise effective preventive strategies

against substance use. The present study was designed to know the

magnitude of substance use and its risk factors among a group of

street children in Delhi.

Methods

The study was conducted in an observation home

for boys in Delhi that provides temporary shelter to children in

need of protection. These children are mainly homeless street

children.

A pilot study was conducted on 30 inmates of the

observation home in January 2002 in which the substance use rate was

found to be 50%. At 10% allowable error, the sample size was

calculated as 100. Based on the admission rate of 25 children per

month, it was estimated that about 125 boys would be available for

study in 5 months, allowing an attrition rate of 20%.

All the boys between 6-16 years who were brought

to the observation home between February to June 2002 were included.

At admission, the boys underwent psychological screening and IQ

testing whenever required by trained psychologists. The criteria for

exclusion were (a) mental retardation defined as IQ £70 (b)

inability of the subject to understand either Hindi or English.

The age of the child was taken from the official

records and was determined by the Juvenile Welfare Board at the time

of admission. The study tools consisted of a self-developed,

semi-structured questionnaire about child’s social and demographic

back-ground. This questionnaire was pretested on 30 inmates of the

observation home in January 2002 and suitably modified. The study

subjects were interviewed regarding substance use anytime before

coming to observation home and the knowledge of its harmful effects.

The informed written consent of the observation home authorities was

obtained.

Statistical Methods

For data entry, EPI-INFO version 2000 was used.

Chi-square test and Fishers’ exact test were applied to detect any

significant association. Odds ratios were also calculated.

Multivariate analysis was done using binomial logistic regression

and adjusted odds ratios were calculated using SPSS 7.5 version. P

value less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Out of the 130 boys admitted to observation home

during the study period, 10 (7.7%) were excluded due to mental

retardation, (n = 4, 3.1%) and their inability to understand either

Hindi or English (n = 6, 4.6%). Of the remaining 120, five (4.2%)

refused to give consent. The final sample consisted of 115 boys aged

between 6 to 16 years.

Table I shows the socio-demographic

characteristics of study subjects. Majority had runaway from homes.

The average age of leaving home was 9.1 years. A total of 68.7%

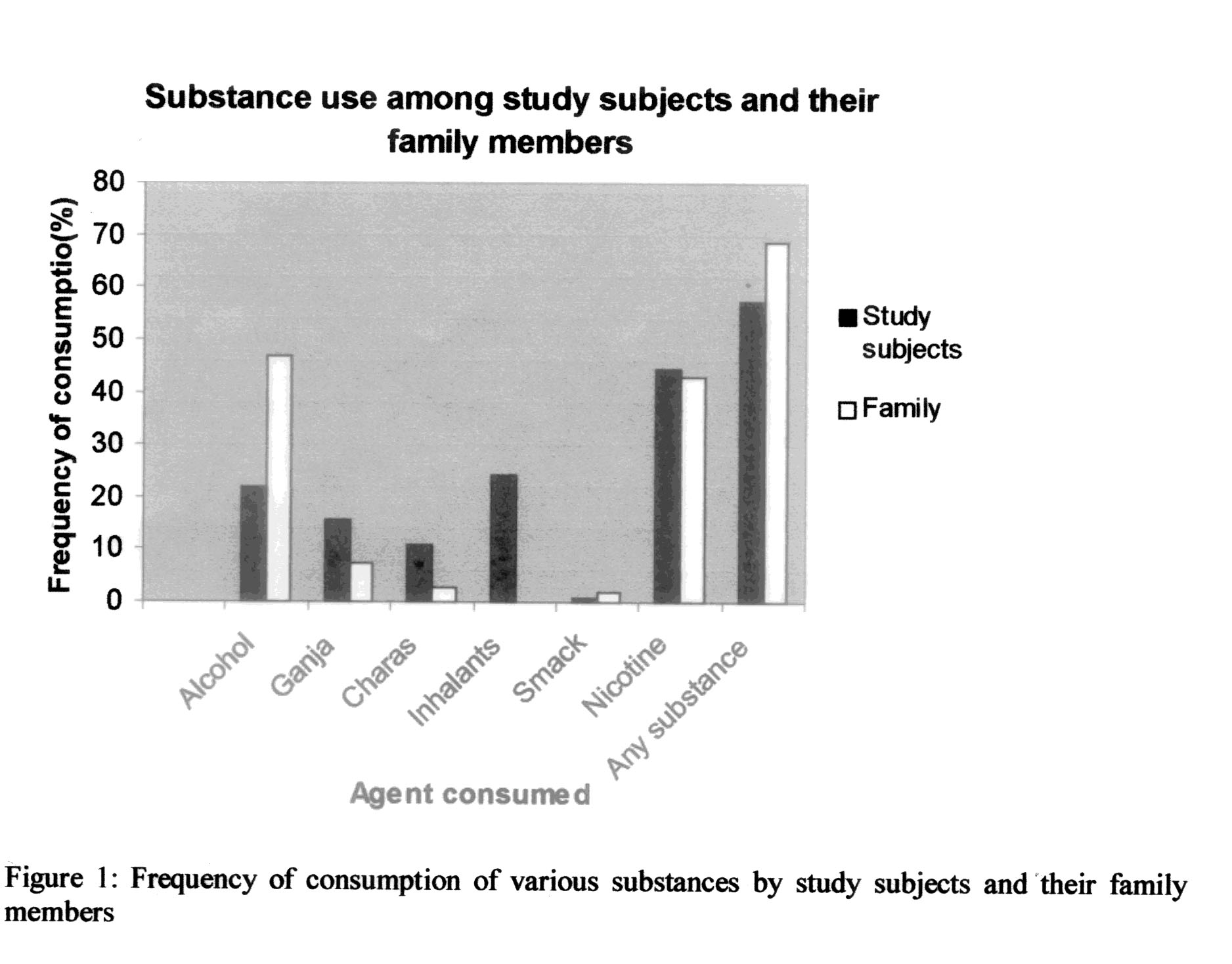

subjects reported substance use in their family (Fig. 1)

among whom 86% reported substance use by the father.

Risk factor

|

Substance use (%)

N = 155

|

Odds ratio

(95% CI)

|

P value

|

Place of origin

|

|

0.56

|

|

|

Rural

|

25 (21.7)

|

|

|

Urban

|

41 (35.7)

|

Nuclear Family

|

49(42.6)

|

2.6(1.1,6.7)

|

0.03

|

Death of father

|

12(10.4)

|

–

|

0.59

|

Death of mother

|

14(12.2)

|

|

0.85

|

Presence of step parents

|

11(9.6)

|

–

|

0.10

|

Domestic violence

|

48 (41.7)

|

2.46 (1.04, 5.87)

|

0.04

|

Maltreatment at home

|

40 (34.8)

|

4.5 (1.9, 10.7)*

|

0.0002

|

Runaway from home

|

57 (49.6)

|

3.08 (1.04, 9.4)

|

0.04

|

Substance use in family

|

50 (43.5)

|

|

0.13

|

Working children

|

60 (52.2)

|

3.7 (0.8, 19.4)

|

0.04

|

*Adjusted odds ratio = 4.7 (95% CI: 2.1, 10.4)

Substance use in children

Among the children interviewed, 57.4% (n = 66)

had indulged in substance use any time in their life. The minimum

age at starting substance use in our study was 5.5 years. The most

common substance consumed was nicotine, as cigarettes or "bidis’ and

"gutkha" (Fig. 1). Inhalant / volatile substance use in the

form of sniffing of adhesive glue, petrol, gasoline, thinner and

spirit was reported by one fourth of children. Twenty per cent of

children reported having sold cigarettes; "bidi" and "gutkha" while

2.5% had been anytime employed in preparation of "charas"

cigarettes.

The harmful effects of substance use named by

children were lung problems (28.2%) like "burning of lungs" and

tuberculosis (6%), some stomach ailment like stones, rupture and

bloody vomiting (12%), cancer (10.9%), death (10%), blackening of

teeth and rupture of cheeks (7.3%), closing of heart or kidney

stones (5%). Thirty per cent denied any knowledge about this issue.

Risk factors for substance use among study

subjects

The results of univariate analysis are shown in

Table 1. Substance use was significantly associated with

domestic violence, maltreatment of the child, nuclear families,

running away from home, and working status of the child. The rural

or urban origin, native state, age of the child and his literacy

level were not significantly associated with substance use.

Multiple logistic regression was applied taking

Substance use as dependent variable and domestic violence,

maltreatment, nuclear family, runaway status and working status as

independent covariates. After regression analysis, maltreatment of

the child was the only variable that reached significant value (Table

I).

It was noted that the knowledge of harmful

effects was more among children who had indulged in substance use

but there was no statistically significant difference. The older

children (11 to 16 years) had more knowledge than younger children

(p >0.05). Children revealed that this knowledge was based on their

own experiences and the information provided by their parents, by

peer group and during health education classes organized by some

voluntary organizations.

Discussion

A sizable proportion (over 50%) of children

coming to observation homes were found to indulge in substance use.

The fact that children had access to a large variety of intoxicating

substances, reflected ineffective implementation of the existing

legislations, namely the Narcotics and Psychotropic Substances Act,

1985 and The Delhi Anti-Smoking and Non-Smoking Health Protection

Act, 1996(7). A study on street children in Bombay, Calcutta, Delhi

and Hyderabad also revealed high rates of substance use among

runaway boys(4).

Running away exposes children to stressful life

on streets, which accompanied by lack of parental care and

supervision and easy access to intoxicating substances, creates an

atmosphere conducive for indulging in substance use. Maltreatment of

the child emerged as the only significant predictor (adjusted OR =

4.7) of substance use in the present study. The results are similar

to other studies(8-10).

The knowledge of harmful effects did not deter

children from indulging in substance use. This factor needs

consideration while devising preventive interventions against

substance use.

It was found that substance use in the family did

not increase the risk of substance use in children. This finding is

different from other studies(1,11). The most common agents consumed

were nicotine and alcohol. Other workers have also reported similar

findings(9, 12).

The present study has some limitations. The

results are based on the information given by children, who may have

underreported because of social stigma attached to consumption of

intoxicating substances. Also, information about the frequency,

regularity and duration of consumption was not available to allow

identification of physical or psychological drug dependence. The

results at best give an estimate of substance use patterns.

The observation home authorities should use the

period of detention of children to implement focused preventive

interventions against substance use. This may involve early

diagnosis, treatment and rehabilitation of substance dependants, and

counseling of parents at the time of family restoration of child

regarding long term effects of maltreatment of children.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Pranay

Bhanu, Medical officer and staff of "Prayas" observation home for

boys, New Delhi, Ms Nirmata Kureel, Mrs Govil and the interns from

the batch of 2002, Maulana Azad Medical College, for their active

support and co-operation for this research.

Contributors: DP developed the concept and

design of the study, collected the data, analyzed, interpreted the

data and wrote the draft and final paper. GSM revised the draft and

gave approval of the version to be published. MMS helped in

conceptualizing and designing the study, analysis and interpretation

of the data, drafting and revising the article. RS helped in

statistical analysis and interpretation of data.

Conflict of interest: None stated.

Funding: None.