There is high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in adolescents,

especially females [1]. 25 hydroxyvitamin-D [25(OH)D] is the main

circulating metabolite of vitamin D, and its concentration in serum

reflects vitamin D stores. Serum concentrations of 1, 25(OH)

2D

increase by 50%–100% over pre-pregnancy levels during the second

trimester, and by 100% during third trimester, which is required for

fetal skeletal growth. In a population with a high prevalence of vitamin

D deficiency and poor dietary calcium intake, the problem is likely to

worsen during pregnancy and may cause significant consequences in the

newborn, including rickets and tetany [2,3]. This study was undertaken

to determine the prevalence of hypovitaminosis D in women in labor, and

in cord blood of their offspring.

This study was conducted from September 2013 to March

2014 in two branches of CloudNine Hospital in the city of Bengaluru,

Southern India. Pregnant women in labor were sequentially enrolled. They

were on regular maintenance dose of calcium (500 mg/day) and vitamin D

(400 IU/day). Women on any drugs that affect vitamin D levels or on

higher supplemental dose were excluded from the study. Those with a

known history of rheumatoid arthritis, disorders of thyroid, parathyroid

or adrenals, hepatic or renal failure, metabolic bone disease, type 1

diabetes mellitus, or malabsorption were excluded. Women with preterm

labor or antenatal suspicion of low birth weight babies were not

included in the study.

Maternal blood samples were collected during labor,

and cord blood samples were collected soon after delivery. The blood

samples were analyzed at Acquity Labs using Liquid Chromatography Mass

Spectrometry (LCMS/MS). The reference range of 25(OH)D for both maternal

and cord blood was taken as 20-80 ng/mL. A level of less than 20 ng/mL

was considered as hypovitaminosis-D.

|

|

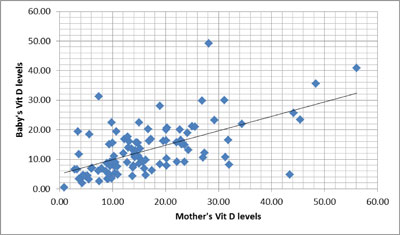

Fig. 1 Correlation of mothers

25-hydroxy vitamin D levels with cord blood vitamin D levels.

|

A total of 106 mothers and cord blood samples were

studied. The mean (SD) maternal vitamin D level was 16.3 (10.3) ng/mL.

Seventy-five mothers (70.7%) had hypovitaminosis-D. The mean (SD) cord

blood vitamin D level was 12.8 (8.5) ng/mL Eighty-eight newborns (83%)

had hypovitaminosis D. Among 75 mothers with hypovitaminosis D, 70

(93.3%) and blood samples had low vitamin D levels whereas 61.3% (n=18)

cord blood samples from 31 mothers having normal vitamin-D levels had

hyporitaminosis D. There was a significant (r=0.6; P<0.001)

correlation between maternal and cord blood vitamin D levels.

The limitation of our study was that we did not

quantify the sunlight exposure and did not record dietary calcium intake

or maternal nutritional status and skin color. Cord blood calcium and

PTH levels were also not done. Several reports confirm the high

prevalence of hypovitaminosis-D among pregnant women in South Asia

[4,5]. A strong correlation between maternal and cord blood levels has

also been reported earlier [6-8].

At present, vitamin D supplementation is not a part

of antenatal care programs in India. The US National Academy of Sciences

mentions 400 IU/day as the reference dietary intake during pregnancy but

several investigators worldwide are arguing for revised guidelines for

higher vitamin D allowance during pregnancy and lactation [9,10]. Our

study showed high prevalence of hypovitaminosis D in women in labor and

their newborns. This may call for vitamin D supplementation to mothers

or their newborns.

Contributors: PK: collection of data, analysis

and the initial manuscript was prepared; AS, KK, SVG, SS: reviewed

critically, helped in finalizing the manuscript and approved the final

manuscript.

Funding: None; Competing Interests: None

stated.

References

1. Rajeswari J,

Balasubramanian K, Bhatia V, Sharma VP, Agarwal AK. Aetiology and

clinical profile of osteomalacia in adolescent girls in northern

India. Natl Med J India. 2003;16:139-42.

2. Delvin EE, Salle BL, Glorieux FH, Adeleine P,

David LS. Vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy: Effect on

neonatal calcium homeostasis. J Pediatr. 1986;109:328-34.

3. Purvis RJ, Barrie WJ, MacKay GS, Wilkinson EM,

Cockburn F, Belton NR. Enamel hypoplasia of the teeth associated

with neonatal tetany: A manifestation of maternal vitamin D

deficiency. Lancet. 1973;2:811-4.

4. Goswami R, Gupta N, Goswami D, Marwaha RK,

Tandon N, Kochupillai N. Prevalence and significance of low

25hydroxyvitamin D concentrations in healthy subjects in Delhi. Am J

Clin Nutr. 2000;72:472-5.

5. Datta S, Alfaham M, Davies DP, Dunstan F,

Woodhead S, Evans J, et al. Vitamin D deficiency in pregnant

women from a non-European ethnic minority population: An

interventional study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;109:905-8.

6. Nicolaidou P, Hatzistamatiou Z, Papadopoulou

A, Kaleyias J, Floropoulou E, Lagona E, et al. Low vitamin D

status in mother-newborn pairs in Greece. Calcif Tissue Int.

2006;78:337342.

7. Sachan A, Gupta R, Das V, Agarwal A, Awasthi

PK, Bhatia V. High prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among pregnant

women and their newborns in Northern India. Am J Clin Nutr.

2005;81:1060-64

8. Kazemi A, Sharifi F, Jafari N, Mousavinasab N.

High prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among pregnant women and

their newborns in an Iranian population. J Women’s Health.

2009;18:835-9.

9. Hollis BW, Wagner CL. Assessment of dietary

vitamin D requirements during pregnancy and lactation. Am J Clin

Nutr. 2004;79:717-26.

10. Dratva J, Merten S, Ackermann-Liebrich U. Vitamin D

supplementation in Swiss infants. Swiss Med Weekly. 2006;136:473-81.