|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2021;58:675-681 |

|

Framework to

Incorporate Leadership Training in Competency-Based

Undergraduate Curriculum for the Indian Medical Graduate

|

|

Sumita Sethi, 1 Henal

Shah,2 Avinash Supe3

From Department of 1Ophthalmology, BPS GMC for Women, Khanpur,

Sonepat, Haryana; Department of 2Psychiatry,

Topiwala National Medical College and BYL Nair Charitable Hospital,

Mumbai, Maharashtra; and 3Department of Surgical Gastroenterology and

Medical Education, Seth GS Medical College and KEM Hospital, Mumbai,

Maharashtra.

Correspondence to: Dr Sumita Sethi, Coordinator Medical Education

Unit, BPS GMC for Women, Khanpur, Sonepat, Haryana.

Email:

sumitadrss@rediffmail.com

Received: December 16, 2020;

Initial review: December 27, 2020;

Accepted: February 06, 2021.

Published online: April 17, 2021;

PII: S097475591600314

|

The new competency-based curriculum recognized the

importance of leadership skills in physicians and has outlined

competencies that would lead to attaining this goal. To prepare the

Indian medical graduates as effective healthcare leader, there is no

universal approach; it is desirable that the institutes organize the

leadership competencies into an institutional framework and integrate

these vertically and horizontally in their curriculum in a longitudinal

manner. We describe the rationale for incorporating formal leadership

training in the new competency-based undergraduate curriculum and

propose a longitudinal curricular template utilizing a

mixed/multi-modality approach to teach and apply leadership

competencies.

Keywords: Competency-based medical education, Physician leader.

|

|

T he recently revised

Graduate Medical Education regulations (GMER) recognized

‘leader and member of the health care team and system’ as one of

the roles for the Indian medical graduate (IMG) [1]. With a

vision to develop an IMG who is globally relevant, this was a

desirable step. It was aligned to Accreditation Council for

Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), which requires students to

demonstrate the ability to ‘work effectively as a member or

leader of a healthcare team or other professional group’ [2]. While broad outlines are provided in the

curriculum, steps to implement the competencies and achieve

goals is largely the responsibility of each institute. We herein

describe the rationale for the inclusion of a formal, culturally

sensitive leadership training in undergraduate medical

education, and provide overarching principles of designing an

institutional framework for incorporating leadership training in

Indian medical colleges under the new competency-based

curriculum (CBME).

The Framework

Leadership Competencies

The first and foremost step is to identify

the desired leadership competencies and outcomes; these will

then serve as the basis for creating course objectives and

further guide the institutional framework and all subsequent

details like content and delivery of leadership training. Many

leadership competencies are already described in the new

curriculum [3]; however, these are not comprehensive and institutes may need to

reframe and expand them to precisely describe the leadership

competencies for their students. Ideally a complete set of

leadership competencies should include self-management

competencies (explo-ration and management of self to develop

greater self-awareness and emotional intelligence), team

management competencies (under-standing principles of working

colla-boratively and leading teams in multi-professional

environ-ments), ability to work with healthcare systems and

other focused leadership competencies (e.g., leading change,

setting realistic goals) and behavior or transfer of learning

based competencies (e.g., demonstration as successful team

leader in actual conditions, networking) [4-8].

Teaching Learning Methods

Once competencies have been identified and

defined; these will then guide the learning experiences that

will be used to deliver the leadership training. Methodologies

described for leadership training are vast, methods such as

group discussions and collaborative work, interactive lectures,

sharing narratives, presentations, demons-trations, use of media

clips and role play activities have been used previously [9-13].

Based on an extensive literature review of teaching learning

methods in leadership and teamwork training [5,6,9-14]

and from our experience of introduction of

institutional student leadership program [15], we propose the

following methodology for teaching learning of leadership and

teamwork principles:

Activities designed to enable an exploration

of self: ‘Who you are is how you lead’ [5,13]; it is

of foremost importance that a leader knows and understands

himself well so that he can identify areas for improvement [4].

The leadership journey for the student

will require an in-depth understanding of self so that one can

constantly learn from own experiences and deal with the

volatile, unpredictable, complex and ambiguous (VUCA) nature of

heathcare system [16]. We suggest tools such as SWOT analysis (for

self-exploration of one’s strength and weakness), changing

‘self-talk’ (for building self-image and improving

self-confidence, reflective writing (for developing deeper

knowledge of self) etc. in form of small group interactive

discussions to generate awareness of self and for developing

attributes like strong emotional intelligence and resilience.

Activities designed to understand leadership

and teamwork principles: Ability to work with others in a

team has been identified as an essential skill for a leader [7].

We suggest tools such as Myers Briggs type

inventory (MBTI); small group interactive activities aiming at

highly specific team related skills like Color blind, Mission to

Burundi; games based on group dynamics and stages of team

building; role plays based on difficult conversations, conflict

management, communication and negotiation skills to help them

learn about the underlying principles of team management, group

dyna-mics and common barriers to effective team working [17,18]. Use of appreciative leadership principles

of inquiry, illumination, inclusion and inspiration as a method

of positive strength-based leadership to create change would be

a useful model [19].

Experiential learning: Team-based

experiential learning activities have been accepted to be the

most effective for practicing leadership skills [7,14].

Students are asked to identify an issue or

concern in clinical, community or educational setting and

execute its solution through a standard framework that includes

defining the problem, communicating with team members and

stakeholders, preparing a timeline, deciding a solution to the

problem and implementation strategy. However, before designating

any assignment as team task, it is important to understand the

concept of ‘task interdependence’ i.e., the extent to which team

members depend on one another for task completion; if a task is

insufficiently complex and can be completed by an individual

working alone, then it should not be labelled as a team task

[20]. Some examples

of team based experiential learning tasks are student leadership

activities like leading a team for a seminar or a competition,

leading and participating in inter-professional teams in

hospitals or rural or mobile units, participating in audits and

utilizing clinical practice guidelines to plan comprehensive

effective patient care in multi-disciplinary settings.

Reflective practice: Reflecting on

an experience and subsequent analysis facilitate incorporation

of behavioral changes into practice, help in exploring its

relevance to past personal experiences and identifies

opportunities in future to achieve more desirable outcome

[17,18,21]. Equally

important is the concept of team reflexivity; there is evidence

that regular team reflexivity helps in improving organizational

outcomes in healthcare [22].

Clinical and community postings: Not

every opportunity for teaching of leadership skills needs to be

formal and explicit; there are certain very informal and readily

available opportunities in our medical curriculum which can be

well utilized. Clinical care rounds are the most commonly

identified curricular approach in literature towards teaching

leadership and teamwork by specifically demonstrating the roles,

responsibilities and interactions among members of

multidisciplinary teams in fulfilling needs of patients [23].

Similarly, much of leadership and teamwork content can also be

folded in the form of community healthcare responsibilities by

providing an opportunity to appreciate teamwork principles

associated with patient management and safety challenges in

community settings. Structured reflections could be obtained to

understand how the students benefitted from the clinical and

community postings.

Opportunity for networking and near peer

assisted teaching learning: Peer networking refers to a

network of like-minded individuals who can support, encourage

and offer opportunities to each other to learn and develop and

also to take on new leadership roles [24,25].

Networking with senior leaders provide a

wide range of contacts, offers an entirely diverse range of

perspectives, and can provide powerful supplementary teaching

mechanisms for leadership development [13,14].

We believe participants in leadership

training will learn best through multi modal learning strategies

involving active participation. Institutes need to identify

methodology for leadership training in alignment to the

respective learning objectives and availability of

institu-tional resources. Readers are referred to some other

publications for more detailed discussion of teaching learning

methodology for leadership [10,18].

Assessment Methods

The assessment plan should focus on

leadership competencies pre-identified and defined in the

insti-tutional framework. During the clinical/community

postings, students can be asked to reflect on any one incident

wherein team-based care had a positive effect on patient care

and another incident where dysfunctional team collaboration and

failure of effective communication amongst team members and

leader resulted in a major lapse in patient care. While the

students are learning to reflect on an experience, it is

important to make them understand to go beyond a mere

description of events; instead, they should analyze and gather

critical evidence of learnings from the event and how they will

apply these learnings for their development as a leader.

Students should be encouraged to undertake various change

initiatives in hospital and community settings; these can be

discussed in the student leadership cell, highlighting the key

areas of teamwork and deliberating on the leadership challenges

that were involved. These can be assessed by reflective writing

assignments and scored by a rubric, with a pre-decided score

designated for a particular level of competency. E-portfolio can

be used for the whole documentation process including various

reflective writing sessions, experiential learning activities

with critical analysis and comments for satis-factory

performance, record of student’s participation in other

leadership activities like student organizations and community

participation.

An important point to ensure is that students

are being assessed on ‘doing’ in addition to ‘learning’ of

leadership traits. During the implementation of leadership

program at our institute, the participants completed at least

one team based experiential learning assignments in hospital

and/or community settings with multisource feedback on the

assignments [15]. These were presented in the student leadership

cell and critically analyzed by a panel of faculty members;

those who performed exceptionally well were felicitated by

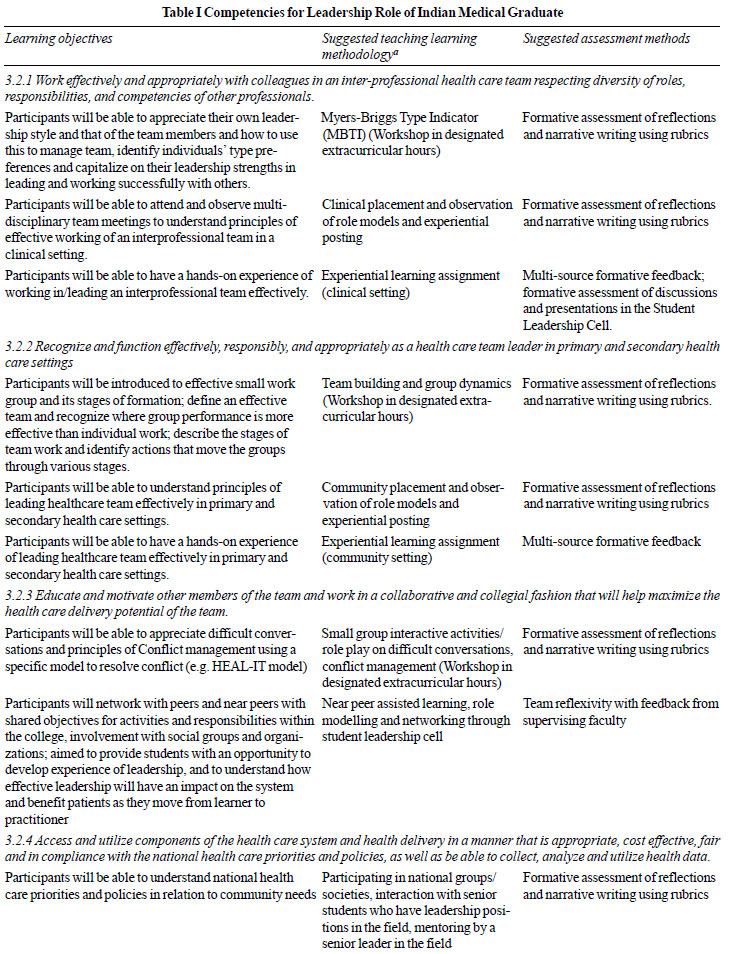

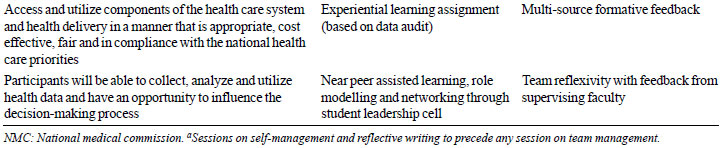

institutional student leadership awards. Table I

describes a few leadership competencies from the document [3]

and suggests the corresponding teaching learning and assessment

methods. These are just suggestions and it is up to the

institute to decide how to approach the particular competency.

If required, any of the validated leadership assessment

instruments readily available in literature may be utilized

[26], ensuring that it is aligned with the institutional

framework and the pre-decided leadership model.

|

|

Evaluation

We suggest a mixed method design including

both quantitative and qualitative methods of evaluation.

Qualitative methods of evaluation like focus group discussions,

structured interviews or interactive feedback sessions are

helpful in understanding of students’ perspectives and the

underlying factors, which makes the whole learning process

effective. In our leadership program, students shared their

leadership journey though reflections written at the end of each

session which were later qualitatively analyzed through content

analysis [15]. Questionnaire-based feedback usually target

participants’ perceptions (Kirkpatrick level-1) and thus may not

truly represent effectiveness of the program; targeting level-2

(learning of leadership skills) and 3 (transfer of learned

skills to real life situations) is desirable. This can be well

achieved through evaluation of the experiential learning

activities and ensuring long term follow up for concrete results

like changes in organizational practices.

The Timetable

Three block experiences can be created and

incorporated in the timetable vertically and horizontally in the

CBME viz., block-1 for introduction to basic teamwork and

leadership principles, block-2 for experiential learning through

clinical/community postings and electives and block-3 for

networking and mentoring.

Block-I: Introduction to key leadership and

teamwork principles: Extracurricular hours in phase-I and II

can be utilized for introducing participants to key

self-manage-ment and team management principles longitudinally

through methodology as described earlier. Timings and duration

of individual sessions can be decided by the institute; however,

group size should not exceed more than fifteen students to

ensure an effective interaction of all participants. Sessions of

self-management should precede those of team management,

following the basic principle that one needs to manage ‘self’

first and then ‘others’. Reflective practice needs to be

initiated early and practiced throughout; sufficient

opportunities for this are already available in the curriculum

e.g., small group teaching activities such as problem-based

learning sessions and tutorial/seminar presentations can be

explored as opportunities for leadership training from the first

year onwards. Anatomy dissection teams are their first

professional exposure to teamwork and a good opportunity to

illustrate basic principles of group dynamics. Discussions can

be initiated on how to define roles and responsibilities of

members, identify one’s own leadership style, establish team

goals, lay down strategies for improved team performance,

illustrate success and frustrations within the team etc.

Similarly, in second professional year, when the clinical

postings are initiated, a pharmacology session can be integrated

with clinical case discussion wherein the student learns the use

of available literature in pharmacology to plan an effective

multidisciplinary treatment plan for the patient.

Block-2: Experiential learning through

clinical and community postings and elective posting:

Further leadership training can be continued as an optional

4-weeks elective (block-1) through the leadership cell; since

students will also be continuing their clinical and community

postings, there will be lots of opportunities for reinforcement

and application of what has been learnt. Specific modules can be

developed in community health or chronic illness or in emergency

medicine with pre-defined learning objectives e.g., the chronic

diseases modules can be used to understand the importance of

working with other health professionals, while at the same time,

having a particular health care professional as patient’s care

coordinator. Small group discussions, student presentations and

reflections may be used and students can be given exercises

addressing leadership and teamwork directly related to the

modules. Above all, this is the most appropriate time for

students to ‘do’ what they have learnt, they should complete at

least two team based experiential learning assignments during

the elective posting; examples and assessment methods of team

based experiential learning assignments have already been

discussed.

Block-3: Networking and near peer assisted

learning: In third professional year part-2, students with

particular interests can attend activities held by the

leadership cell outside curricular hours and undertake

activities for bringing changes in organizational practices,

they also continue networking and mentoring the new

participants. Members of the club can meet once in a month or

fortnightly to discuss and deliberate on various teamwork and

leadership related issues.

The Rationale

Medical students have always been expected to

evolve as physician leaders and take on leadership roles from

the beginning of their professional career; it is ironical that

the traditional undergraduate medical curriculum did not address

leadership training formally. Recognition of ‘leader and member

of healthcare team’ as a role for the IMG in the new CBME

curriculum is a much-desired move towards ushering in formal

leadership training; however, there are a few questions that

need to be addressed before planning leadership training. The

first and foremost is ‘whether leadership can be taught’; if

yes, what leadership models will guide the whole process? What

will be the goals for the program and what will be the most

effective learning experiences to achieve them? When should the

training be initiated and how will the leadership competencies

be assessed? We have tried to address these questions while

proposing this longitudinally incorporated framework for

leadership training. Yes, leadership does consist of a series of

definable skills that can be well taught; while a few may have

inherent characteristics that make them better leaders, adequate

training and experiences could create successful leaders [7,27].

Different models and theories like

transformational leadership, authentic leadership, servant

leadership, self-leadership and appreciative leadership have

their own characteristics [7,26,28-30]; it is important to develop feasible models

for various branches of health-care, in different regions of the

country for respective institutions. Another important point to

consider is ‘when’ and ‘how’ to introduce this training; one

school of thought is that once negative perceptions develop as a

result of negative role modelling during clinical postings, it

becomes more difficult to change; other school of thought is

that such training will be effective only when sufficient

clinical experience has been gained [17]. There is no approach

which is specifically ‘right’ or ‘wrong’; it is essential that

the institute has a clarity for the specific aims of the program

and design the framework accordingly. Having an institutional

commitment is desirable; Janke, et al. [8] emphasized the

importance of weaving leadership development into the mission

and goals of the institute; including financial support, support

of administrators responsible for resource management,

in-organization recognition awards and appropriate faculty

development and reward systems [8].

Leadership training is not just meant to

prepare students for particular leadership roles; instead, it is

targeted to develop strong personal and professional values and

a range of non-technical skills such as communication skills,

strong emotional intelligence, negotiation skills, etc. which

will allow them to lead across professional boundaries and

influence many facets of life including healthcare [4].

Any one-time opportunity for development

of leadership will not be sufficient and the importance of

providing continuous opportunities for practicing leadership

skills, networking and mentoring cannot be over emphasized.

There are student bodies, student clubs, community and other

group activities in almost all medical schools; these

opportunities can be explored and utilized for formal leadership

training. Chaudry, et al. [31] proposed a medical leadership

society at medical schools as an easier to implement solution to

cater to the growing demand for leadership training for students

who demonstrate a special interest in leadership. We suggest the

introduction of student leadership cells with opportunities for

networking and peer mentoring to keep them engaged in leadership

activities in different stages of professional development.

Challenges and Limitations

Some institutes may already have one or the

other formal or informal leadership program in place; however,

if such training is being introduced for the first time in the

institute, many challenges would be expected. Hiring

professional managers or trainers might work as a one-time

solution to initiate the program but if it has to run as an

institutional program, it is important that faculty members are

sufficiently trained. There will be requirement of faculty

development activities targeting leader-ship skills to help the

faculty develop as trainers as well as role models. In the

initial phase of introduction of leadership training, not having

sufficient number of trained faculty in the institute will be a

major limitation. Under such circumstances, if training is made

compulsory for all students, it will tend to inherently dilute

the quality and the whole drive because there will simply be too

many students and too less trainers. On the other hand, if only

a few students are included, the whole concept of including

leadership as a core competency for students will not be

fulfilled. As an intermediate solution, we suggest utilizing

near peer mentoring through the institutional leadership cell

till the faculty development program on leadership is completed.

Furthermore, we will be mistaken by assuming that any one-time

course will make our students evolve as leaders; to achieve this

goal, longitudinal integration of leadership training in the

curriculum is to be ensured. This will require meticulous

planning and involvement of all the stakeholders i.e., members

of curriculum committee and medical education unit and other

faculty members. Another major challenge will be evaluation of

the program. As discussed earlier, only quantitative form of

evaluation will not be sufficient and more of qualitative

information targeting higher Kirkpatrick’s levels of learning

will be required; this will create severe time limitations.

Above all, long-term follow-up and evaluation will be needed to

provide concrete results in the form of change in organizational

practice as a result of leadership training.

CONCLUSION

The new competency-based curriculum not only

addresses a well-recognized gap in our medical undergraduate

training by recognizing the role of ‘leader’ for the IMG but

also provides scope for formal leadership training in the

already crowded undergraduate curriculum, through dedicated

extracurricular hours and electives. It is exciting to propose a

formal framework for explicit leadership training including team

training, community and clinical experiences, student leadership

opportunities, experiential learning, mentoring and networking.

The framework can be finalized by the institute itself according

to its own desired competencies, preferred teaching methods and

available resources. We believe that this framework could be

aligned with the current curriculum, without stretching either

the time or the resources. It is of foremost importance to have

institutional commitment and develop a supportive atmos-phere,

conducive for the students to evolve as leaders and for faculty

as role models through administrative and financial support,

appropriate allotment of resources, and training and incentives

for faculty.

Funding: None; Competing interest:

None stated.

REFERENCES

1. Medical Council of India. Regulations

on Graduate Medical Education 2019 - Addition as Part II of

the Regulations on Graduate Medical Education, 1997;

E-gazette. Accessed Dec 2, 2019. Available from:

mciindia.org/documents/Gazette/GME-06.11. 2019

2. The Accreditation Council for Graduate

Medical Education (ACGME). The outcome project 2014.

Accessed February 12, 2019. Available from:

www.acgme.org.

3. National Medical Commission:

Competency based Undergraduate curriculum for the Indian

Medical Graduate 2018. Accessed January 7, 2018. Available

from:

https://www.nmc.org.in/information-desk/for-colleges/ug-curriculum

4. Hargett CW, Doty JP, Hauck JN, et al.

Developing a model for effective leadership in healthcare: A

concept mapping approach. J Healthc Leadersh. 2017;9:69-78.

5. NHS Institute for Innovation and

Improvement and Academy of Medical Royal Colleges (NHS III).

Medical leadership competency framework: enhancing

engagement in medical leadership. 3rd edition. 2010 NHS

Institute for Innovation and Improvement and Academy of

Medical Royal Colleges.

6. Webb AM, Tsipis NE, McClellan TR, et

al. A first step toward understanding best practices in

leadership training in undergraduate medical education: A

systematic review. Acad Med. 2014; 89: 1563-70.

7. Varkey P, Peloquin J, Reed D, et al.

Leadership curriculum in undergraduate medical education: A

study of student and faculty perspectives. Med Teach.

2009;31:244-250.

8. Janke KK, Nelson MH, Bzowyckyj AS, et

al. Deliberate integration of student leadership development

in doctor of pharmacy programs. American J Phar Edu.

2016;80:2.

9. Shulman LS. Signature pedagogies in

the professions. Daedalus. 2005;134:52-9.

10. Jenkins DM. Exploring signature

pedagogies in undergraduate leadership education. Journal of

Leadership Education. 2012; 11:1-27.

11. Russell SS. An overview of

adult-learning processes. Urologic Nursing. 2006;26:349-52.

12. Sethi S. Leadership development

programs in undergraduate medical education: Understanding

the need, Best practices and Challenges. In:

Jespersen EA, editor. Exploring the opportunities and

challenges of medical students. NOVA Publishers; 2019.

p.32-57.

13. Till A, Mc Kimm J, Swanwick T. Twelve

tips for integrating leadership development into

undergraduate medical education. Med Teach. 2018;40:1214-20.

14. Warren OJ, Carnall R. Medical

leadership: Why it’s important, what is required, and how we

develop it. Postgrad Med J. 2011;87:27-32.

15. Sethi S, Chari S, Shah H, Aggarwal R,

Dabas R, Garg R. Implementation and evaluation of leadership

program for medical undergraduate students in India. In:

Abstract book of Annual conference of AMEE (Association for

Medical Education in Europe): The virtual conference; 2020

September 7-9.p.166.

16. Till A, Dutta N, McKimm J. Vertical

leadership in highly complex and unpredictable health

systems. British J Hosp Med. 2016;77: 471-5.

17. Banerjee A, Slagle JM, Mercaldo ND,

et al. A simulation-based curriculum to introduce key

teamwork principles to entering medical students. BMC

medical education. 2016;16:295.

18. Shah H, Ladhani Z, Morahan PS, et al.

Global leadership model for health professions education

Part 2: Teaching/learning methods. The J Leadership Educ.

2019;18:193-203.

19. Orr T, Cleveland-Innes M.

Appreciative leadership: Supporting education innovation.

International Review of Research in Open and Distributed

Learning. 2015;16:235-41.

20. West MA, Lyubovnikova J. Illusions of

team working in health care. J Health Organ Manag.

2013;27:134-42.

21. Sandars J. The use of reflection in

medical education: AMEE Guide No. 44. Medical Teacher.

2009;31:685-95.

22. Schippers MC, Edmondson AC, West MA.

Team reflexivity as an antidote to team

information-processing failures. Small Group Research.

2014;45:731-69.

23. O’Connell MT, Pascoe JM.

Undergraduate medical education for the 21st century:

Leadership and teamwork. Fam Med. 2004;36: S51-6.

24. Gaufberg EH, Batalden M, Sands R, et

al. The hidden curriculum: what can we learn from third-year

medical student narrative reflections? Acad Med.

2010;85:1709-16.

25. Chen TY. Medical leadership: An

important and required com-petency for medical students. Ci

Ji Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2018;30:66-70.

26. Houghton JD, Dawley D, DiLiello TC.

The abbreviated self-leadership questionnaire (ASLQ): A more

concise measure of self-leadership. Int J Leadership

Studies. 2012;7:216-32.

27. Clyne B, Rapoza B, George P.

Leadership in undergraduate medical education: Training

future physician leaders. R I Med J. 2015;98:36-40.

28. Trastek VF, Hamilton NW, Niles EE.

Leadership models in health care-case for servant

leadership. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2014;89:374-81.

29. Stoller JK. Developing physician

leaders: A perspective on rationale, current experience, and

needs. Chest. 2018;154:16-20.

30. Judge TA, Bono JE. Five-factor model

of personality and transformational leadership. Journal of

Applied Psychology. 2000;85: 751-65.

31. Chaudry A, Amar Sodha AN. Expanding management and

leadership education in medical schools. Adv Med Educ Pract.

2018;9:275-78.

|

|

|

|

|