|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2014;51:

550-554 |

|

Comparative Short term Efficacy and

Tolerability of Methylphenidate and Atomoxetine in Attention

Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

|

|

Jasmin Garg, Priti Arun and BS Chavan

From Department of Psychiatry, Government Medical College & Hospital,

Chandigarh, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Jasmin Garg, Department of Psychiatry,

Government Medical College and Hospital, Sector 32, Chandigarh, India.

Email: jasmin.arneja@gmail.com

Received: January 07, 2014;

Initial review: February 06, 2014;

Accepted: May 09, 2014.

|

Objective: To compare the short term efficacy and tolerability of

methylphenidate and atomoxetine in children with Attention deficit

hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Design: Open label randomized parallel group

clinical trial.

Setting: Child Guidance Clinic of a tertiary care

hospital of Northern India from October 2010 to June 2012.

Participants: 69 patients (age 6-14 y) with a

diagnosis of ADHD receiving methylphenidate or atomoxetine.

Intervention: Methylphenidate (0.2-1 mg/kg/d) or

atomoxetine (0.5-1.2 mg/kg/d) for eight weeks.

Main outcome measures: Treatment response (>25%

change in baseline Vanderbilt ADHD Diagnostic Parent Rating Scale

(VADPRS); Vanderbilt ADHD Diagnostic Teacher Rating Scale (VADTRS);

Clinical Global Impression Severity Scale (CGI-S) at eight weeks and

adverse effects.

Results: Treatment response was observed in 90.7%

patients from methylphenidate group and 86.2% patients of atomoxetine

group at an average dose of 0.45 mg/kg/d and 0.61 mg/kg/d, respectively.

The patients showed comparable improvement on VADPRS (P=0.500),

VADTRS (P=0.264) and CGI-S (P=0.997). Weight loss was

significantly higher in methylphenidate group (-0.57±0.78 kg; P=0.001),

and heart rate increase was observed at higher rate in atomoxetine group

(7± 9 bpm; P=0.021).

Conclusion: Methylphenidate and atomoxetine are

efficacious in Indian children with ADHD at lesser doses than previously

used. Their efficacy and tolerability are comparable.

Trial Registration No.: CTRI/2011/08/001981

Keywords: ADHD, Adverse events, Efficacy, Treatment dose.

|

|

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is

one of the common chronic problems affecting school-age children [1],

and have poor family and peer relations [2]. Without effective

treatment, such children may develop long-term handicaps [3]. According

to current clinical guidelines, psycho-stimulants, especially

methylpheni-date, are considered the first line treatment of ADHD [4,5].

However, methylphenidate is associated with risk of variation in mood

state, motor tics, and abuse potential [6].

Atomoxetine is a nonstimulant that is approved for use in

ADHD as the second line treatment [4,5]. The studies comparing

therapeutic responses to stimulants and atomoxetine in ADHD have been

conducted in Western countries, and have produced conflicting results

[7-13]. The present study was carried out to compare the efficacy and

tolerability of methylphenidate and atomoxetine in Indian children with

ADHD.

Methods

Patients were recruited from those attending the

Child Guidance Clinic of a tertiary care hospital in Northern India from

October 2010 to May 2012. Children (age 6 to 14 years) diagnosed as

ADHD, according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

Disorders-IV-Text Revision [14], and having moderate to severe illness

as assessed by Clinical Global Impressions Severity Scale (CGI-S) [15]

were eligible for inclusion. Patients with history of

non-response or adverse drug reactions to methylphenidate or atomoxetine

in the past, those who had taken any medication for ADHD in past one

month, or those with history of heart disease, seizures, pervasive

developmental disorder, substance abuse, mental retardation or tic

disorder were excluded.

Parents brought the patients to the child guidance

clinic themselves or when referred by school. Before initiating

treatment, electrocardiogram (ECG) was performed for each patient to

rule out any cardiac abnormality.

Written informed consent was obtained from both

parents/guardians and the children. The principles enunciated in the

Declaration of Helsinki [16] and Indian Council of Medical Research [17]

were complied with. Clearance was obtained from the Ethics committee of

the Government Medical College and Hospital, Chandigarh.

The patients were allotted to Group A or Group B by

simple randomization as per computer generated table of random numbers.

Patients in Group A received immediate release tablet Methylphenidate

(once or twice daily) while those in Group B received tablet Atomoxetine

(once or twice daily). The drugs prescribed were from standard

pharmaceutical companies, approved by the drug committee of the

institute. Patients were started on tablet Methylphenidate (immediate

release) 5 mg once a day, or tablet Atomoxetine 10 mg once a day, on

their first visit as per Clinical Practice Guidelines of Indian

Psychiatric Society [18]. Efforts were made to increase the dose of

Methylphenidate up to 1mg/kg/day and of atomoxetine up to 1.2 mg/kg/d

once or twice daily depending upon the response and tolerability. Weekly

increments of 5 mg were tried for both methylphenidate and atomoxetine.

Patients were assessed at baseline and once weekly or fortnightly till 8

weeks. On each visit, improvement in symptoms was assessed by Vanderbilt

ADHD Diagnostic Parent Rating Scale (VADPRS) [19]. Vanderbilt ADHD

Diagnostic Teacher Rating Scale (VADTRS) Proforma [20] was sent through

the parents to be filled up by teachers at baseline and at 8 week.

Teachers were contacted telephonically to obtain information about

patients’ classroom behavior and for clarifying VADTRS. CGI-S was also

used to assess the severity of illness at baseline and last follow up

visit.

The various side effects were noted on each

assessment on the Adverse Events Checklist prepared for the study. It

was a semi-structured check list enlisting all the common side effects

of methylphenidate and atomoxetine. The parents were asked to rate the

severity of each side effects produced in their children as mild,

moderate and severe. Those who reported mild side effects were continued

on the same dose. For those who developed moderate severity of side

effects, dose was reduced. Those who rated any adverse effect to be

severe were taken out of the study after stopping the medication. They

were then managed as per standard treatment protocol of the department.

Heart rate and blood pressure were also recorded at each visit.

Laboratory investigations including complete blood counts, renal

function tests and liver function tests were done at baseline, four

weeks and eight weeks. Primary outcome measures were: improvement in

symptoms as assessed by VADPRS, and percentage of patients who developed

various adverse effects for estimation of tolerability. Secondary

outcome measures were: improvement in symptoms as assessed by VADTRS and

CGI-S; and change in patients’ heart rate, blood pressure, weight and

laboratory investigations for assessment of tolerability.

The sample size was calculated based on data from

previous studies that 70% of patients receiving methylphenidate show

improvement of 25% or more in ADHD rating scale [18]. It was planned to

conclude equivalence of atomoxetine with methylphenidate if 25% or more

improvement is seen in 70 ± 30 % of patients. With a power of 70% and an

alpha of 5%, a sample size of 37 per group was calculated. Keeping in

mind a dropout rate of about 5-10%, it was decided to enroll 40 patients

in each group.

Statistical analysis: Data were analyzed using

SPSS version 16.. Significance level was P <0.05 (two tailed).

Fisher’s exact test and Chi square test were used to compare

categorical variables. Independent sample t-test and paired t-test were

administered for analysis of parametric data. Mann Whitney test and

Wilcoxon signed rank test were used for analysis of CGI-S score as this

parameter was not normally distributed.

Results

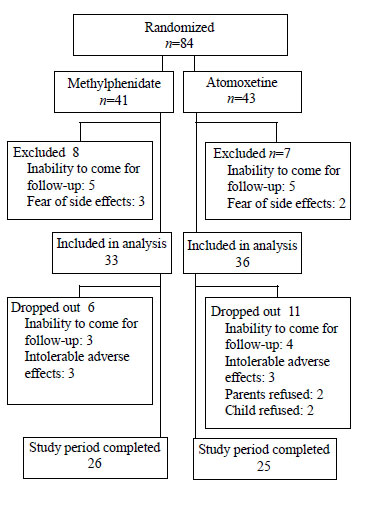

Out of 84 children randomized to receive either drug,

17 refused after baseline assessment, and were excluded from analysis.

Of remaining, 33 were in methylphenidate group and 36 were in

atomoxetine group (Fig. 1). In both methylphenidate and

atomoxetine groups, combined type of ADHD was the commonest, followed by

inattention type and hyperactive/impulsive type. The baseline

parameters, including VADPRS total score, VADPRS subscale scores, VADTRS

score and CGI-S score were comparable between the two groups (Table

I).

|

|

Fig. 1 Patient flowchart.

|

TABLE I Baseline Characteristics of the Two Groups

|

Variable |

Methylphenidate |

Atomoxetine

|

|

(N=33) |

(N=36) |

|

Age (y)* |

8.47 ± 2.22 |

8.66 ± 2.44 |

|

Weight (kg)* |

28.54 ± 9.45 |

25.26 ± 8.25 |

|

Males, No. (%) |

27 (81.8%) |

29 (80.6%) |

|

Type of ADHD |

|

Inattention |

9 (27.3%) |

6 (16.7%) |

|

Hyperactive/impulsive

|

2 (6.1%) |

4 (11.1%) |

|

Combined |

22 (66.7%) |

26 (72.2%) |

|

Comorbidity |

|

ODD |

15 (45.5%) |

22 (61.1%) |

|

Conduct Disorder |

1 (3%) |

6 (16.7%) |

|

VADPRS* |

|

Total |

51. 18 ± 10.86 |

55.03 ± 14.44 |

|

Inattention |

20.88 ± 3.81 |

19.42 ± 5.50 |

|

Hyperactivity

|

17.85 ± 6.47 |

19.72 ± 5.79 |

|

CGI-S* |

5.03 ± 0.95 |

5.22 ± 0.79 |

|

VADTRS* |

41.11 ± 14..22 |

46.11 ± 14.61 |

|

VADPRS = Vanderbilt

ADHD Diagnostic Parent Rating Scale; CGI-S = Clinical Global

Impression Severity Scale; VADTRS = Vanderbilt ADHD Diagnostic

Teacher Rating Scale; ODD = Oppositional Defiant Disorder; All

values in No.(%) except * values in mean (SD). |

Out of the total 69 recruited patients, 51 (74%)

could be followed up for the eight weeks. Seventeen patients (6 from

methylphenidate group and 11 from atomoxetine group) discontinued the

treatment at some point. There was no significant difference between

mean (SD) baseline VADPRS total score of retained [52.14 (11.99)] and

dropped out [57.29 (14.87)] patients (P = 0.153).

There was significant improvement over 8 weeks in

both methylphenidate and atomoxetine groups when measured on VADPRS

total score, inattention subscale score and hyperactivity subscale

score. The comparative change in VADPRS (total and subscales) scores

from baseline to 8 weeks was not significant (Table II).

TABLE II Change in VADPRS, VADTRS and CGI-S Scores from Baseline to 8 Weeks

|

Variable

|

Methylphenidate |

Atomoxetine |

|

Baseline |

Week

|

Mean |

Intra- |

Base- |

Week |

Mean |

Intra- |

Inter- |

|

|

8 |

difference |

group |

line |

8 |

difference |

group |

group |

|

n = 33 |

n= 26 |

|

P value |

n = 36 |

n = 25 |

|

P value |

P value |

|

VADPRS |

|

Total |

51. 18 (0.86) |

24.69 (10.29) |

-26.69 (1.99) |

<0.001 |

55.03 (14.44) |

23.60 (17.21) |

-29.32 (15.49) |

<0.001 |

0.500 |

|

Inattention |

20.88 (3.81) |

10.375 (5.39) |

-10.00 (4.38) |

<0.001 |

19.42 (5.50) |

7.961 (5.82) |

-11.23 (4.93) |

<0.001 |

0.690 |

|

Hyperactivity

|

17.85 (6.47) |

9.46 (5.11) |

-9.23 (6.14) |

<0.001 |

19.72 (5.79) |

9.00 (6.92) |

-10.20 (7.30) |

<0.001 |

0.610 |

|

CGI-S |

5.03 (0.95) |

2.92 (0.84) |

-2.04 (1.15) |

<0.001 |

5.22 (0.79) |

3.08 (1.55) |

-2.04 (1.37) |

<0.001 |

0.997 |

|

VADTRS |

41.11 (14.22) |

25.29 (9.20) |

-17.2619(10.12)

|

<0.001 |

46.11 (14.61) |

30.42 (14.51) |

-14.10 (9.41) |

<0.001 |

0.264 |

|

VADPRS: Vanderbilt ADHD

Diagnostic Parent Rating Scale; All values in mean (SD). |

With the criteria of 25% reduction in baseline scores

of VADPRS, 90.7% patients from methylphenidate group and 86.2% patients

from atomoxetine group showed improvement. Three (11.5%) patients in

methylphenidate group and five (20%) in atomoxetine group (P=0.465)

showed less than 25% improvement after 2 months in VADPRS scores even

when maximum therapeutic dose was administered.

There was more than 25% improvement in baseline

VADPRS total score from 3rd

week onwards both in methylphenidate and atomoxetine groups when the

mean (SD) dose administered were 11.59 (2.83) mg/day and 14.03 (3.85)

mg/day, respectively. The mean (SD) dose administered at conclusion of

the study when there was maximum efficacy and tolerability was 17.35

(7.52) mg/day (or 0.62mg/kg/day) in the methylphenidate group and 17.46

(7.22) mg/day (or 0.7mg/kg/day) in the atomoxetine group (Web Fig.

1).

According to the adverse effects checklist prepared

for the study, 18 (55%) patients from methylphenidate group and 20 (56%)

from atomoxetine group developed side effects during the course of the

study. The commonest reported adverse effect in both groups was reduced

appetite. There was no significant difference between two groups in the

occurrence of various adverse effects (Table III). Three

patients in each group dropped out due to development of adverse effects

rated as severe by the parents. These side effects were irritability,

fatigue, drowsiness, headache and reduced appetite.

TABLE III Adverse Effects in Methylphenidate and Atomoxetine Groups

|

Adverse effects |

Methylphenidate |

Atomoxetine |

P

|

|

n=32 No. (%) |

n=36 No. (%) |

value |

|

Headache

|

4 (12.5) |

2 (5.6) |

0.410 |

|

Nausea |

1 (3.1) |

1 (2.8) |

1.000 |

|

Vomiting |

1 (3.1) |

1 (2.8) |

1.000 |

|

Decreased appetite |

14 (43.8) |

12 (33.3) |

0.378 |

|

Pain abdomen |

3 (9.4) |

0 (0) |

0.099 |

|

Irritability |

2 (6.3) |

7 (19.4) |

0.157 |

|

Fatigue |

2 (6.3) |

1 (2.8) |

0.598 |

|

Drowsiness |

1 (3.1) |

6 (16.7) |

0.110 |

|

Urinary incontinence |

1 (3.1) |

2 (5.6) |

1.000 |

|

Sadness |

0 (0) |

1 (2.8) |

1.000 |

|

Rash |

1 (3.1) |

0 (0) |

0.471 |

|

Hypersalivation |

1 (3.1) |

0 (0) |

0.471 |

|

Insomnia |

1 (3.1) |

0 (0) |

0.471 |

When assessed on VADTRS and CGI-S, there was

significant improvement over 8 weeks in both methylphenidate and

atomoxetine groups. Teacher’s report was available for 78% of patients.

The change in VADTRS score and CGI-S score from baseline to 8 weeks were

comparable in methylphenidate and atomoxetine groups (Table II).

There was no significant change in the mean (SD) heart rate from

baseline 87 (9)/min to 90 (8)/min at week 8 in methylphenidate group (P=0.312).

However, in atomoxetine group, there was significant increase in heart

rate from baseline 84 (6) to week 8, 92(8)/min with mean difference 7

(9)/min and P =0.021. There was no significant decrease in weight

(in kg) in methylphenidate group from baseline to week 4 [Mean

difference (SD), -0.166 (0.747); P=0.286], but there was

significant decrease at week 8 [-0.576 (0.783); P=0.001]. In the

atomoxetine group, there was no significant weight differences.

There were no significant differences in

hematological and biochemical parameters from baseline to week 4 and

week 8 in either of the groups.

Discussion

The present trial documented that both

methylphenidate and atomoxetine produced statistically significant and

comparable improvements in the symptoms of ADHD, as reported by parents

and teachers. The average dose of both methylphenidate and atomoxetine

which produced significant clinically improvement in the patients of

present study was much lesser than in earlier studies.

Improvements produced by both atomoxetine and

methylphenidate in this study were comparable to that reported in

earlier clinical trials [21]. Absence of teacher’s assessment had been a

potential shortcoming in majority of earlier studies comparing relative

efficacy of the two drugs [7-12]. In our study, the rate of occurrence

of adverse events was comparable to that reported in earlier studies

[7,11,12]. Decreased appetite was the commonest adverse event in both

the groups and methylphenidate led to a little more weight loss than

atomoxetine. The present study had limitations of being an open labelled

study without allocation concealment. Placebo arm was not included due

to ethical considerations. Moreover, lesser number of patients could be

included in the analysis of the study due to the high dropout rate. A

high dropout rate has also been reported in an earlier study from India

[22].

Nonetheless, the present study has important clinical

implications. Equivalent therapeutic efficacy and response rate was

found with lesser doses administered for both the drugs than study

populations in other countries. Atomoxetine was found to be comparable

in efficacy and tolerability methylphenidate in short term. Future

studies with larger sample sizes may be taken up in each subtype of ADHD

with longer duration of follow up in order to document long term effects

of treatment.

Contributors: All authors were involved in concept

and design of study; data collection, analysis and interpretation;

manuscript drafting and its final approval.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None stated.

|

What is Already Known?

• Methylphenidate is the first line and

atomoxetine is the second line treatment of ADHD.

What This Study Adds?

• Methylphenidate and atomoxetine have

comparable efficacy in Indian Children with ADHD.

• Dose of methylphenidate and atomoxetine for therapeutic

response seems to be much lower in Indian population than

documented from other settings.

|

References

1. Faraone SV, Sergeant J, Gillberg C, Biederman J.

The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: is it an American condition? World

Psychiatry. 2003;2:104-13.

2. Kidd PM. Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder

(ADHD) in children: rationale for its integrative management. Altern Med

Rev. 2000;5:402-28.

3. Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Bessler A, Malloy P,

LaPadula M. Adult psychiatric status of hyperactive boys grown up. Am J

Psychiatry. 1998;155:493-8.

4. Pliszka S, AACAP Work Group on Quality Issues.

Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and

adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad

Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:894-921.

5. Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity

Dis-order; Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management,

Wolraich M, Brown L, Brown RT, DuPaul G, et al. ADHD: Clinical

practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents.

Pediatrics. 2011;128:1007-22.

6. Greydanus DE, Nazeer A, Patel DR.

Psychopharmacology of ADHD in pediatrics: current advances and issues.

Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2009;5:171-81.

7. Kratochvil CJ, Heiligenstein JH, Dittmann R,

Spencer TJ, Biederman J, Wernicke J, et al. Atomoxetine and

methylphenidate treatment in children with ADHD: a prospective,

randomized, open-label trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.

2002;41:776-84.

8. Kemner JE, Starr HL, Ciccone PE, Hooper-Wood CG,

Crockett RS. Outcomes of OROS methylphenidate compared with atomoxetine

in children with ADHD: a multicenter, randomized prospective study. Adv

Ther. 2005;22:498-512.

9. Sangal RB, Owens J, Allen AJ, Sutton V, Schuh K,

Kelsey D. Effects of atomoxetine and methylphenidate on sleep in

children with ADHD. Sleep. 2006;29:1573-85.

10. Prasad S, Harpin V, Poole L, Zeitlin H, Jamdar S,

Puvanendran K, et al. A multi-center, randomized, open-label

study of atomoxetine compared with standard current therapy in UK

children and adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder

(ADHD). Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:379-94.

11. Wang Y, Zheng Y, Du Y, Song DH, Shin YJ, Cho SC,

et al. Atomoxetine versus methylphenidate in pediatric

outpatients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a randomized,

double-blind comparison trial. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2007;41:222-30.

12. Newcorn JH, Kratochvil CJ, Allen AJ, Casat CD,

Ruff DD, Moore RJ, et al. Atomoxetine and osmotically released

methylphenidate for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity

disorder: acute comparison and differential response. Am J Psychiatry.

2008;165:721-30.

13. Yildiz O, Sismanlar SG, Memik NC, Karakaya I,

Agaoglu B. Atomoxetine and methylphenidate treatment in children with

ADHD: the efficacy, tolerability and effects on executive functions.

Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2011;42:257-69.

14. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and

Stati-stical Manual of Mental Disorder, 4th ed. Text Revision.

Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

15. Busner J, Targum SD. The clinical global

impressions scale: A pplying a research tool in clinical practice.

Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2007;4:28-37.

16. William JR. The Declaration of Helsinki and

public health. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:650-2.

17. Indian Council Medical Research. Ethical

Guidelines for Biomedical Research on Human Participants. New Delhi:

Director-General, Indian Council Medical Research; 2006.

18. Gautam S, Batra L, Gaur N, Meena PS. Clinical

practice guidelines for the assessment and treatment of attention

deficit/hyperactivity disorder. In: Gautam S, Avasthi A, editors.

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Clinical Practice Guidelines for

Psychiatrists in India. Jaipur: Indian Psychiatric Society; 2008. p.

23-42.

19. Wolraich ML, Lambert W, Doffing MA, Bickman L,

Simmons T, Worley K. Psychometric properties of the Vanderbilt ADHD

diagnostic parent rating scale in a referred population. J Pediatr

Psychol. 2003;28:559-67.

20. Wolraich ML, Feurer ID, Hannah JN, Baumgaertel A,

Pinnock TY. Obtaining systematic teacher reports of disruptive behavior

disorders utilizing DSM-IV. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1998;26:141-52.

21. Hanwella R, Senanayake M, de Silva V. Comparative

efficacy and acceptability of methylphenidate and atomoxetine in

treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and

adolescents: a meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:176.

22. Sitholey P, Agarwal V, Chamoli S. A preliminary

study of factors affecting adherence to medication in clinic children

with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Indian J Psychiatry.

2011;53:41-4.

|

|

|

|

|