The pertussis vaccine is

effective in preventing Bordetella pertussis

infection and death, and the risk is high in young

infants who do not receive the vaccine [1]. B.

pertussis infection in siblings is considered a

common route of transmission to young infants [2].

Currently, three brands of DPT-IPV (acellular

pertussis, diphtheria and tetanus toxoids, and

inactivated polio combined) are used in Japan. All

contain pertussis toxin and filamentous

hemagglutinin (6-23.5 and 23.5-51.5 µg/0.5 mL,

respectively), and one contains additional pertactin

and fimbriae (5 and 1 µg/0.5 mL, respectively) [3].

Children receive a total of four doses of DPT-IPV:

three primary doses at the ages of 3, 4, and 5

months, and one booster dose at 18 to 23 months as a

national routine vaccination. In 2018, vaccine

coverage for the four doses was 95.0%, 95.7%, 96.2%,

and 96.2%, respectively [4]. The preschool pertussis

vaccination booster is used in some Asian countries

like India, but not in Japan [5]; even though Japan

has one of the highest primary pertussis vaccination

rates in the world [6]. We, herein present data from

an outbreak of pertussis, which occurred mainly in

lower-grade school children without preschool

vaccination boosters.

A retrospective chart-based study

was conducted on patients who visited the Saiwai

Pediatric Clinic, Tokyo, Japan, with persistent

cough. Patients were examined by board-certified

pediatricians for suspected pertussis and received a

laboratory diagnosis between August and September,

2018. In accordance with the Pediatric Respiratory

Infection Practice Guidelines in Japan [7],

diagnostic tests for pertussis were defined as

positive by either nasal swab loop-mediated

isothermal amplification (LAMP) or anti-pertussis

IgM/IgA in sera. The positive and negative

predictive rates of LAMP are 100% and 97%,

respectively (Loopamp Pertussis Detecting Reagents

D; Eiken Chemical Corporation). The sensitivity of

anti-pertussis IgM and IgA are 29-56% and 25-44%,

respectively and the specificities are 93% and 99%,

respectively (Novagnost Bordetella pertussis

IgM/IgA; Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics KK). The

patient background (sex, age, and vaccination

history), and diagnosis method were collected.

Statistical analyses included a

bar graph review and Fisher exact test of

age-distribution comparisons. We used SPSS

Statistics 25 (IBM Corp.) and BellCurve for Excel

for Windows (Social Survey Research Information Co.

Ltd.) software programs.

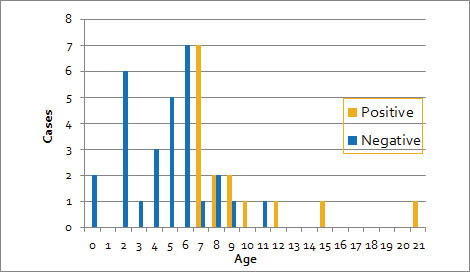

Of the 44 patients (age

distribution: 0-21 years, median: 6 years), data of

15 patients who were diagnosed with

laboratory-confirmed pertussis (age: 7-21 years,

median: 8 years) and 29 patients who were pertussis-negative

(age: 0-11 years, median: 5 years) were compared.

All patients (n=15) who were pertussis-positive

but only 17% (n=7) of patients who were

pertussis-negative were elementary school age and

older (P< 0.001) (Fig. 1). All 16

preschool children were negative. Excluding

serodiagnosis cases (3 positive cases, 1 negative

case), a significant difference in age distribution

(P<0.001) was also observed. When a 2 × 2

table was prepared with 7 years of age as the

cut-off value, the sensitivity, specificity,

positive predictive rate, and negative predictive

rates were 100%, 83%, 75%, and 100%, respectively.

|

|

Fig. 1 Pertussis

test results and age distribution.

|

None of the 44 patients had a

history of preschool vaccination booster at around

5 years of age. Of 15 children who were positive, 14

patients had received four routine vaccinations and

the booster history was uncertain in 1 patient. Of

29 children who were negative, 26 patients had

received four routine vaccinations, but two

patients who were a few months old were vaccinated 0

and 2 times, and the booster history was uncertain

in another patient.

The absence of pertussis in

preschool children and the presence of pertussis in

lower-grade schoolchildren suggest the need of

additional preschool vaccinations. It has been

reported that the prevalence of anti-pertussis toxin

titer in individuals aged 4 to 7 years declines to

26-38% even among regular vaccines [8]. During our

research period, the Japanese Society of Pediatrics

began to recommend that preschool children aged 5 to

6 years receive a DPT vaccination, but this is on a

voluntary basis [9].

This report covers a limited

number of cases in a single institution, and the

question remains of whether the data on sensitivity

and specificity for pertussis at age 7 years or

older can be generalized. However, the all-Japanese

pertussis cases reported indicate that over 60% of

cases are between the ages of 6 and 15 years,

peaking at the age of 7 years [10], which is

consistent with the age distribution reported

herein.

We experienced a pertussis

epidemic in elementary school-age children, all of

whom had been immunized with at least three doses of

primary DPT-IPV immunization. We believe that

popularizing the preschool pertussis vaccination is

important in order to eliminate the infection source

for young infants. Consideration should be given to

routine preschool pertussis vaccination boosters in

Japan if larger community-based studies confirm our

findings.

Ethics approval: Keio

University School of Medicine Ethical Committee,

Tokyo, Japan; No. 20190205, dated December 26, 2019.

Contributors: TK, MS, AM, TT:

designed the study; TK, MS, AM: collected and

analyzed data: TK, MS, AM, TT: wrote the manuscript;

AM,TT: critically reviewed the manuscript. All

authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: None; Competing

interests: None stated.

1. Kavitha TK, Samprathi M,

Jayashree M, et al. Clinical profile of critical

pertussis in children at a pediatric

intensive care unit in Northern India. Indian

Pediatr. 2020; 57:228-31.

2. Skoff TH, Kenyon C, Cocoros N,

et al. Sources of infant pertussis infection in the

United States. Pediatrics. 2015; 136:635-41.

3. Nakayama T. Current status of

pertussis and the need for vaccines. Pediatrics of

Japan. 2019;60:1137-44 (in Japanese).

4. Ministry of Health, Labour and

Welfare. Implementation of routine immunizations.

Accessed September 20, 2020. Available from:

http://www.mhlw.go.jp/topics/bcg/other/5.html

5. World Health Organization. WHO

vaccine-preventable diseases: monitoring system.

2020 global summary. Accessed September 20, 2020.

Available from:

https://apps.who.int/immunization_ monitoring/globalsummary/

6. UNICEF. Immunization coverage

estimates data visualization. Accessed September 20,

2020. Available from:

https://data.unicef.org/resources/immunization-coverage-estimates-data-visualization

7. Ouchi K, Okada K, Kurosaki T.

Guidelines for the management of respiratory

infectious diseases in children in Japan.

2017;53:236-40.

8. National Institute of

Infectious Diseases. Seroprevalence of pertussis in

2013, Japan. 2013. Accessed September 20, 2020.

Available from:

https://www.niid.go.jp/niid/images/iasr/2017/02/444tef05.gif

9. Japan Pediatric Society.

Vaccination Schedule Recommended by the Japan

Pediatric Society. 2018. Accessed September 20,

2020. Available from:http://www.jpeds.

or.jp/uploads/files/20180801_JPS%20Schedule%20

English.pdf

10. National Institute of

Infectious Diseases. Number of notified pertussis

cases by age and immunization status week 1 to week

48 of 2018, Japan (n=9674). 2018. Accessed

September 20, 2020. Available from:

https://www.niid.go.jp/niid/images/iasr/2019/01/467tef04.gif