The Government of India has recently released the

National and State level factsheets of the Rapid Survey on Children (RSoC)

that was conducted jointly by the Ministry of Women and Child

Development and UNICEF [1]. This state-level dataset was awaited as it

is about a decade from the previous comparable data from the third

National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3) in 2005-06 [2]. The recently

released Global Hunger Report and the Global Nutrition Report portend

some of these gains [3,4]. We focus on two key aspects: (i) the

emerging trends, and (ii) and the contemporary policy discourse.

What’s Up and What’s Down?

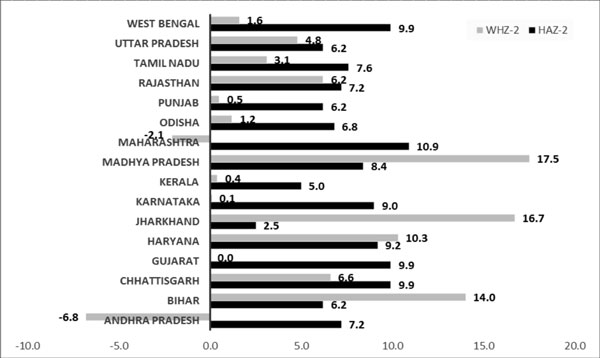

There is a significant improvement in the child

malnutrition levels between NFHS-3 and the RSoC. The prevalence for

stunting in under-five children has decreased from 48% to 38.7%; and

there is also a decline in prevalence of underweight (42.5% to 29.4%)

and wasting (from 19.8% to 15.1%). The absolute levels of child

malnutrition continue to be high. Most states showed improvements in

levels of stunting; remarkable gains (among the large states) were noted

in Andhra Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Gujarat, and Madhya Pradesh. Jharkhand

reported very little improvement in stunting (2.5%) but large gains in

wasting (16.7%) (Fig. 1).

|

|

Fig. 1 Percentage changes between

NFHS3 and RSOC in stunting and wasting.

|

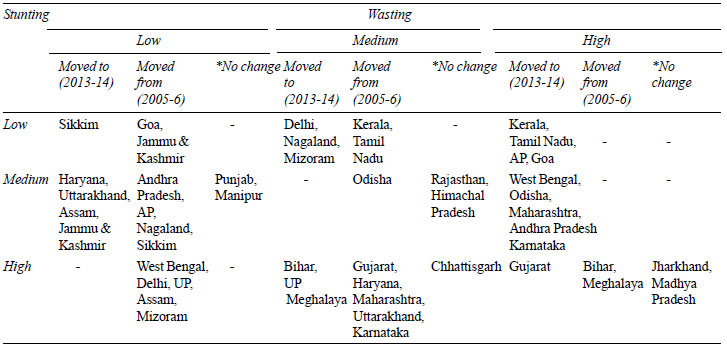

The distribution of stunting and wasting in states

showed interesting shifts. With declines in stunting, some states have

recorded higher prevalence of wasting, a phenomenon noted as well in the

changes between NFHS-2 and NFHS-3. Table I shows the

distribution by RSoC data by following the earlier method of mapping

inter-state distribution of acute and chronic malnutrition by computing

terciles for wasting and stunting and tracking the changes in their

respective positions [5,6]. A notable change is Bihar and Gujarat

switching places between high wasting and high stunting category and

medium wasting and high stunting category. This is explained by Gujarat

reporting no change in the status of wasting despite an impressive 9.9

percentage point improvement in stunting. With decreases in stunting,

quite a few states now feature in the axis of high wasting (Table

I).

|

TABLE I Distribution of Stunting and Wasting

Across States |

* from NFHS-3 (2005-06) to RSoC (2013-14); UP: Uttar Pradesh;

AP: Arunachal Pradesh. |

A comparison of levels of stunting in Indian and

African children with similar multi-dimensional poverty index is

instructive - Bihar (49.4%) and Liberia (42%) / Sierra Leone (45%);

Jharkhand (47.3%) and Angola (29%) / Mozambique (43%); Madhya Pradesh

(41.6%), Chhattisgarh (43%), Uttar Pradesh (50.6%) and Senegal (19%)/

Malawi (48%)/ D R Congo (25%). The South Asian Enigma therefore

continues (despite recent declines), and requires an understanding

beyond anthropometric indicators.

There is large-scale improvement in exclusive

breastfeeding rates among children under six months of age (from 46.4%

to 64.9%). Of concern is the decline in infant and young child feeding

(IYCF) practices; this was already quite poor. The proportion of

children aged 6-23 months who had a minimum dietary diversity has

significantly gone down. The NFHS reports minimum dietary diversity

separately for breastfed and non-breastfed children (the average of both

has been reported here). The RSoC factsheet on the other hand has not

made such a distinction. The full report and data may clarify if there

is an issue of definitional inconsistencies between the two surveys.

What’s not new?

High levels of stunting indicate continuing

large-scale prevalence of chronic malnutrition. Other correlates of

social determinants such as open defecation and sanitation, while

recording some improvement, continue to be abysmally low. Critical

indicators that continue to be worrying are low birth weight, early age

at marriage and low adolescent BMI. Equally serious are issues of

complementary feeding, dietary diversity and breastfeeding indicators.

High prevalence of chronic malnutrition with acute

exacerbations exemplifies chronic poverty and multiple deprivations [7].

The percentage of children in the 6-35 months age group accessing

supplementary nutrition is as low as 22.8% in Uttar Pradesh, while it is

much higher at 65.3% in Andhra Pradesh, 70.3% in Himachal Pradesh, 82.8%

in Chhattisgarh and 89.2% in Odisha.

Treatment as an Attractive Illusion

In this epidemiologic backdrop, two news items call

for a careful examination. A civil society collective appealed to

policymakers (in a press release) on July 23, 2015 to "declare

malnutrition as a medical emergency to save India’s children dying of

hunger" [8]. The Press Trust of India quoted the Union Minister for

Tribal Affairs on August 4 that his Ministry will identify and document

medicinal herbs helpful in the treatment of malnutrition [9].

The moot question: can malnutrition be ‘treated’?

Current mainstream global notions draw upon African experiences where

Severe Acute Malnutrition (SAM) is triggered by acute crises such as

drought, crop failure and civil wars. Classical SAM is a medical

emergency (with high risks of mortality) requiring feeding with ready to

use therapeutic foods (RUTF) along with other medical interventions. The

predominant form of malnutrition in India is significantly different

from the classical SAM and standardized protocols for treatment are not

as effective, requiring much longer duration to achieve targeted weight

gains even with RUTF. This is on account of high levels of underlying

stunting. Stunting signifies chronic undernutrition and has no scope for

‘cure’ in a therapeutic mode.

Programmatic implications are thus primarily

two-fold: (i) blend and combine multiple approaches for

management of malnourished children in community and institutional

settings; and (ii) a breadth of interventions to address

multi-dimensional poverty and prevent chronic malnutrition through

long-term and multi-sectoral efforts at building community capacity and

support structures. Critical weaknesses include shortage of

pediatricians even at the district hospital level (recently released

rural health service data point to shortfalls up to 90% in high burden

states), and a cogent strategy for continuum of care [10].

Bridging the Gap

Gaps remain in nutrition programming in the country

at all levels. The release of the much-delayed RSoC data is welcome.

Regrettably, there is no institutional mechanism in place to ensure

regular availability of anthropometric data at national, state and

district levels. The NFHS-4 seems to be indefinitely delayed. The first

step towards meaningful planning and monitoring would be to put in place

a regular and comprehensive nutrition surveillance system and

incorporate it with the Mother and Child Tracking System (MCTS). It is

hoped that this, long with a multi-sectoral comprehensive approach

towards tackling malnutrition in all its forms, is what the long-awaited

National Nutrition Mission will encompass. The Sustainable Development

Goal 2.2 calls for ending all forms of malnutrition by 2030, including

achieving by 2025 the internationally agreed targets on stunting and

wasting in children under five years of age. It’s a rocky road ahead;

difficult, if not impossible!

1. Rapid Survey on Children 2013-2014. India

Factsheet. Provisional. Ministry of Women and Child Development.

Government of India. Available from: http://wcd.nic.in/issnip/National_Fact%20sheet_RSOC%20_02-07-2015.pdf.

Accessed August 29, 2015

2. International Institute for Population Sciences

(IIPS) and Macro International. 2007. National Family Health Survey

(NFHS-3), 2005-06;I:273.

3. Bread for the World Institute. 2015. Global Hunger

Report: When Women Flourish. We can end Hunger. Washington, DC.

4. International Food Policy Research Institute.

2014. Global Nutrition Report 2014: Actions and Accountability to

Accelerate the World’s Progress on Nutrition. Washington, DC.

5. Bergeron G, Castleman T. Program responses to

acute and chronic malnutrition: divergences and convergences. Adv Nutr.

2012;3:242-9.

6. Dasgupta R, Sinha D, Yumnam V. Programmatic

response to malnutrition in India: Room for more than one elephant?

Indian Pediatr. 2014;51:863-8.

7. Alkire S, Santos ME. Acute Multidimensional

Poverty: A New Index for Developing Countries. United Nations

Development Programme Human Development Reports Research Paper 2010.

8. Express Health News Bureau. Civil Society appeals

to policymakers to declare malnutrition as a medical emergency.

9. Press Trust of India. Centre to collaborate with

Ramdev in finding cure of malnutrition: Union Minister Juel Oram.

Available from:

http://www.news18.com/news/uttarakhand/centre-to-collaborate-with-ramdev-in-finding-cure-of-malnutrition-union-minister-juel-oram-781345.html.

Accessed August 20, 2015.

10. Dasgupta R, Yumnam V, Ahuja S, Roy S. The

Conundrum of continuum of care: Experiences from the NRC model, Madhya

Pradesh. Oral presentation at the South Asia Conference on Policies and

Practices to Improve Nutrition Security, SAC-OP-07-05; 2014 July 30-31,

New Delhi, India. Available from:

http://www.nutritioncoalition.in/thematic-oral-presentations.

Accessed June 16, 2014.