Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH)

refers to accumulation of intra-alveolar red blood cells

originating from alveolar capillaries due to underlying

injury to alveolar microcirculation. The clinical picture

includes hemoptysis, anemia, hypoxemic respiratory failure

with infiltrates on chest X-ray [1,2]. In the absence

of infections or any hemodynamic cause for DAH, anti-neutrophil

cytoplasmic autoantibodies (ANCAs) must be looked for and

ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV) - mainly microscopic

polyangiitis (MPA),Wegener granulomatosis, or Churg-Strauss

syndrome should be considered. We report a case of MPA who

presented with DAH and was further found to have

interstitial lung disease (ILD).

Case Report

A 13-years-old girl presented with

increasing pallor and gradually worsening dyspnea for last

15 days. She had history of recurrent anemia since the age

of two years, requiring multiple ( four times) blood

transfusions. She had intermittent episodes of cough, fever,

arthralgia, anasarca, and dyspnea on exertion for last 10

years. There was no history of bleeding from any site. She

had received antitubercular therapy (6-months course) one

year back, prior to presentation at our hospital. Her birth,

development and family history was non-contributory.

On examination, her heart rate was

142/min, respiratory rate 48/min, blood pressure 102/60 mmHg

and SpO

2 was 92%

on room air. She had severe pallor, grade-3 clubbing, and

non-blanchable erythematous papular rash over both feet.

Chest examination revealed subcostal and intercostal

retractions with fine crepitations audible all over the

chest. Hepatosplenomegaly was present. Growth was well

preserved. Rest of the systemic examination was normal.

Laboratory Investigations: Blood

investigations revealed anemia (hemoglobin 3.3 g/dL),

platelets 120×10

3

/mm3, total

leukocyte count of 5400/mm3

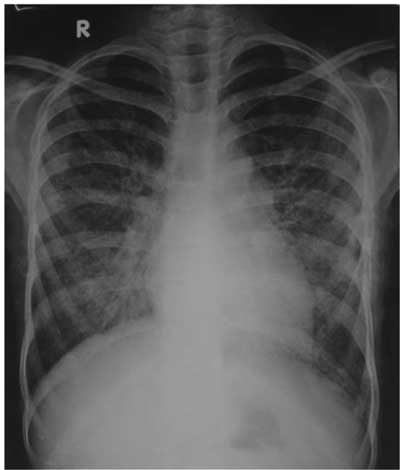

with normal differential count. Past and present radiographs

showed prominent interstitial reticular shadows in the

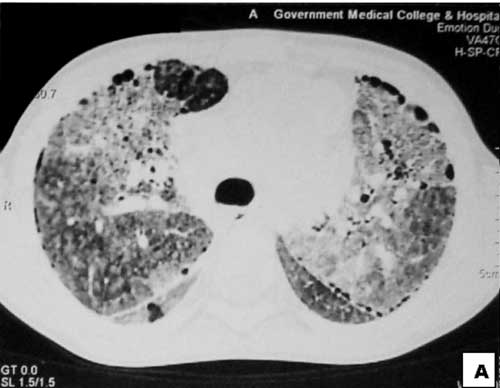

middle and lower zones (Fig.1). HRCT chest

showed diffuse ground glass opacities in bilateral lung

fields and interstitial infiltrates with honeycombing

especially in the lower zones (Fig.2). Lung

function tests showed moderate restriction pattern: forced

vital capacity was <64% predicted), and early small airway

obstruction (mean peak expiratory flow rate was <70%

predicted). Echocardiography revealed mild pulmonary artery

hypertension with moderate tricuspid regurgitation. Prussian

blue staining of sputum for hemosiderin-laden macrophages

was positive with siderophage percentage more than 86 %

corresponding to Golde score >100, confirming DAH [1]. Urine

microscopy and renal function tests were normal. ANCA was

positive by immunoflourescence with a perinuclear staining

pattern and ELISA for antimyeloperoxidase ANCA (MPO-ANCA)

was positive (2.808, cutoff-0.394).

|

|

Fig.1 Chest X-ray shows

prominent interstitial reticular shadows due to

diffuse alveolar hemorrhage.

|

|

|

Fig.2 HRCT of lungs show

bilateral ground glass opacity and interstitial

infiltrates with honeycombing especially in the

periphery.

|

Common infections like malaria, enteric

fever, tuberculosis were ruled out on investigations. Her

ANA and dsDNA were negative. AntiGlomerular Basement

Membrane Antibody and Anti Phospholipid Antibody workup were

negative. Serology for Human Immunodeficiency Virus,

Hepatitis B surface antigen, Hepatitis C and tissue

transglutaminase antibodies were negative. Serum IgE levels

were normal (150IU/mL). Direct Coombs test was negative.

Skin biopsy was unremarkable and did not reveal features of

leucocytoclastic vasculitis.

In view of the multisystem involvement

and positive serology for MPO-ANCA, a diagnosis of MPA was

made. She was started on oral steroids 2 mg/kg/day and

supportive therapy. She went into remission on oral

steroids. After 6 weeks, daily therapy was shifted to

alternate day and then tapered over one year.

Simultaneously, azathioprine was added.

She is on regular follow-up for one year.

She had one relapse in past year which was managed with

short course of steroids. She has remained normotensive,

hepatosplenomegaly has regressed, has had no urinary

complaints or need for blood transfusions (hemoglobin-13.1g/dL),

normal repeat renal functions and, Elisa for MPO-ANCA has

returned to normal.

Discussion

Severe unexplained anemia in a female

with progressive dyspnea and alveolar opacities on chest

imaging, without hemorrhage elsewhere alerted us to the

possibility of DAH. Long history of fever, cough, clubbing,

hepatosplenomegaly, led to the possibility of ILD. Absence

of cutaneous/mucous telangiectasias clinically ruled out

hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Nonspecific

constitutional symptoms, DAH, ILD with sparing of the upper

airways, no asthma/eosinophilia with positive MPO-ANCA

clinched the diagnosis of MPA.

MPA is a non-granulomatous pauci-immune

primary systemic vasculitides which affects small vessels.

Kidneys and lungs are the most frequently affected organs.

Annual incidence rates of MPA is 2.1-17.5 per million [3].

DAH and ILD have both been reported in MPA [4,5].

However, unlike our case, untreated MPA usually are rapidly

progressive and fatal [4]. Though DAH in MPA is usually

acute, rarely DAH has been reported as part of chronic MPA

in adult patients [6]. The index case had a slow indolent

course with frequent exacerbations which has previously not

been reported in a child. Incidence of ILD is 7.2% in MPA.

Diagnosis of ILD is usually based on radiological evidence

on HRCT and/or lung function tests [5]. Generally, lung

biopsy is not recommended for diagnosis [1,2]. It is

considered if DAH is associated with negative serology and

not a part of a systemic disease. Notably our case didn’t

have renal involvement in past 10 years [1,2].

Two main mechanisms have been proposed

for the development of ILD in patients with small vessel

vasculitis. Firstly, the pulmonary fibrosis occurs in

response to pulmonary haemorrhage and secondly, the ANCA

antigens such as MPO undergo translocation to the surface of

neutrophils (possibly in response to proinflammatory

cytokines), and subsequent binding of circulating ANCA

results in neutrophil degranulation and release of reactive

oxygen species, causing injury and consequent fibrosis

[7,8].

Treatment typically includes

corticosteroids, immunosuppressive agents, and occasionally

plasma-pheresis. 90% of patients achieve remission at 6

months. Relapse rates in AAV are 50%; severe

organ-threatening damage and treatment-related adverse

effects occur in 25% of patients. 10% of those refractory to

standard immunosuppressant therapies are at high risk for

death [9]. Serial hemoglobin measurement guides on DAH

control or progression [1]. Disappearance of ANCA is almost

always associated with absence of disease activity [10].

We conclude that DAH should be considered

as a differential diagnosis in recurrent unexplained anemia.

A high index of suspicion and prompt management can reverse

the symptoms quickly.

Contributors: VM: did case management

& data collection, wrote the draft, interpreted the data;

KR: also helped in management and data collection; SK: did

the radiological reporting; SD: gave intellectual inputs to

case management and edited the manuscript. VM will act as

guarantor of the study. The final manuscript was approved by

all authors.

Funding: None; Competing interests:

None stated.

References

1. Cordier JF, Cottin V. Alveolar

hemorrhage in vasculitis: primary and secondary. Semin

Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;32:310-21.

2. Lara AR, Schwarz MI. Diffuse alveolar

hemorrhage. Chest. 2010;137:1164-71.

3. Gibelin A, Maldini C, Mahr A.

Granulomatosis, microscopic polyangiitis, churg-strauss

syndrome and goodpasture syndrome: vasculitides with

frequent lung involvement. Semin Respir Crit Care Med.

2011;32:264–73.

4. Go´mez-Puerta JA, Herna´ndez-Rodríguez

J, Lo´pez-Soto A, Bosch X. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic

antibody-associated vasculitis and respiratory disease.

Chest. 2009;136:1101-11.

5. Arulkumaran N, Periselneris N, Gaskin

G, Strickland N, Ind PW, Pusey CD, et al.

Interstitial lung disease and ANCA-associated vasculitis: a

retrospective observational cohort study. Rheumatology.

2011;50:2035-43.

6. Martínez-Gabarrón M, Enríquez R,

Sirvent AE, Andrada E, Millán I, Amorós F. Chronic pulmonary

bleeding as the first sign of microscopic polyangiitis

associated with autoimmune thyroiditis. Nefrologia.

2011;31:494-5.

7. Birnbaum J, Danoff S, Askin FB, Stone

JH. Microscopic polyangiitis presenting as a

"pulmonary-muscle" syndrome: is subclinical alveolar

hemorrhage the mechanism of pulmonary fibrosis? Arthritis

Rheum. 2007;56:2065-71.

8. Falk RJ, Terrell RS, Charles LA,

Jennette JC. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies

induce neutrophils to degranulate and produce oxygen

radicals in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87: 4115–9.

9. Langford CA. Treatment of

ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:3-4.

10. Geffriaud-Ricouard C, Noël LH, Chauveau D, Houhou S,

Grünfeld JP, Lesavre P. Clinical spectrum associated with

ANCA of defined antigen specificities in 98 selected

patients. Clin Nephrol. 1993;39:125-36.