|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2013;50:

209-213 |

|

Effect of Probiotics on Allergic Rhinitis in

Df, Dp or Dust-Sensitive Children: A Randomized Double Blind

Controlled Trial

|

|

Teng-Yi Lin, Chia-Jung Chen *,

Li-Kuang Chen#, Shu-Hui Wen$,

and Rong-Hwa Jan†

From the Department of Laboratory Medicine and

†Pediatrics, Buddhist Tzu Chi General Hospital; and *Department of

Nursing, #Institute of Medical Sciences, and $Institute of Public

Health, College of Medicin; Tzu Chi University; Hualien, Taiwan.

Correspondence to: Rong-Hwa Jan, Department of

Pediatrics, Buddhist Tzu Chi General Hospital, #707, Section 3,

Chung-Yang Road, Hualien, Taiwan. [email protected]

Received: July 12, 2011;

Initial review: August 17, 2011;

Accepted: April 30, 2012.

Published online: 2012, June 10.

PII:S097475591100603-1

|

|

Objective: To study, we examined the effect of

Lactobacillus salivarius on the clinical symptoms and medication use

among children with established allergic rhinitis (AR).

Design: Double blind, randomized,

controlled trial.

Setting: Hualien Tzu-Chi General

Hospital.

Methods: Atopic children with

current allergic rhinitis received 4 × 109 colony forming units/g of

Lactobacillus salivarius (n=99) or placebo (n=100)

daily as a powder mixed with food or water for 12 weeks. The SCORing

Allergic rhinitis index (specific symptoms scores [SSS] and symptom

medication scores [SMS]), which measures the extent and severity of AR,

was assessed in each subject at each of the visits - 2 weeks prior to

treatment initiation (visit 0), at the beginning of the treatment (visit

1), then at 4 (visit 2), 8 (visit 3) and 12 weeks (visit 4) after

starting treatment. The WBC, RBC, platelet and, eosinophil counts as

well as the IgE antibody levels of the individuals were evaluated before

and after 3 months of treatment.

Results: The major outcome,

indicating the efficacy of Lactobacillus salivarius treatment,

was the reduction in rhinitis symptoms and drug scores. No significant

statistical differences were found between baseline or 12 weeks in the

probiotic and placebo groups for any immunological or blood cell

variables.

Conclusions: Our study demonstrates that

Lactobacillus salivarius treatment reduces rhinitis symptoms and

drug usage in children with allergic rhinitis.

|

|

Allergic rhinitis (AR) is a common childhood

disease that often persists into adulthood. The prevalence of childhood

allergic disease has increased dramatically in recent decades in many

parts of the world, including Taiwan [1]. The prevalence of reported

symptoms of AR in Taiwanese children aged 6-8 and 13-15 years has been

reported to be 29.8% and 18.3%, respectively [1]. The causes of AR are

not well understood, but sensitization to food proteins may play a role.

Children who are atopic and develop dermatitis are at a significantly

increased risk of developing atopic asthma and rhinitis in later

childhood [2]. This immune response includes both IgE antibodies and

helper T cells type 2 (Th2), which are thought to contribute to

inflammation in the respiratory tract. Moreover, sensitization to indoor

allergens (eg, dust mites, cats, and dogs) is strongly associated with

allergic rhinitis.

Probiotics are products or preparations containing

viable numbers of microorganisms that are able to modify the host’s

microflora, thereby producing beneficial health effects [3].

Lactobacilli are considered to induce reactions involving Th1 cells and

to improve allergic diseases. Two lines of argument have provided the

framework for studies on the relationship between bowel flora and

allergic disease. First, lower counts of Enterococci and

Bifidobacteria in infancy have been found in atopic vs.

non-atopic children and these differences precede sensitization [4, 5].

The early colonization of the bowel with probiotic bacteria such as

Enterococci and Bifidobacteria are hypothesized to more

effectively mature the gut mucosal immune system and promote tolerance

to non-bacterial antigens. Secondly, increased gut permeability may lead

to increased exposure to food antigens, which has been associated with

atopic dermatitis (AD) [6]. Probiotics may decrease gut permeability

thereby decreasing systemic exposure to food antigens.

Isolauri, et al. [7] have previously reported

an improvement in the SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index in

milk-allergic infants with mild AD following probiotic-supplemented

hydrolyzed whey formula [8]. Recently, Rosenfeldt, et al. [8],

using a cross-over study design, demonstrated an improvement in the

SCORAD index in older children with AD who were treated with probiotics;

however, the improvement was only significant is allergic patients.

Lactobacillus paracasei may improve the quality of life of

adolescents with perennial allergic rhinitis [9, 10]. The effect of

probiotics on rhinitis, remain controversial [11, 12]. Studies have

demonstrated that oral administration with L. salivarius prior to

and during allergen sensitization and airway challenges leads to a

suppression of various features of the asthmatic phenotypes, including

specific IgE production, airway inflammation, and development of airway

hyperresponsiveness in an animal model [13]. Therefore, it is worth

while examining whether L. salivarius could improve allergic

symptoms in humans. We examined the effect of probiotic treatment on

atopic children with rhinitis. Various specific clinical and immune

parameters were assessed in allergen-sensitive patients before and after

treatment, and were compared with those of untreated (UT)

allergen-sensitive patients.

Methods

The study was conducted in the pediatric clinic of

Hualien Tzu Chi General Hospital between February and December 2009.

Children aged between 6 to 12 years; history of perennial allergic

symptoms for at least 3 years; positive skin prick test (SPT) for Dp, Df

or dust, and Unicap system (Pharmacia Diagnostics, Uppsala, Sweden)

positivity for Dp, Df, or dust (more than class 1) were recruited in the

study. Patients who had previously been treated with immunotherapy, and

those with recurrent respiratory tract and infectious diseases, were

excluded. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of

the Hualien Tzu-Chi General Hospital and informed consent was obtained

from all subjects.

Randomization was performed by doctors, who were not

involved in this study design. All of the enrolled patients were

randomly assigned to the L. salivarius group or the placebo group

according to computer-generated permuted-block randomization. The

selected patients were randomized into two groups (consisting of 120 UT

patients and 120 patients treated with probiotic) taking into account

age, sex, medication scores, type and importance of ocular symptoms

(itching, redness, or weeping), nasal symptoms (sneezing, rhinorrhea,

itching or nasal blockage), and lung symptoms (cough, sputum, dyspnea,

or wheezing). The treatment group received 4 × 10 9

colony forming units/g of Lactobacillus salivarius PM-A0006

supplied by ProMD Biotech Co., Ltd. The control group received a placebo

consisting of microcrystalline cellulose that looked and tasted the same

as the probiotics. All patients who met the eligibility criteria were

randomized into either the probiotic-treated group or the control group.

The powder (500 mg) was given once daily mixed in drink or food. A small

number of older children (>10 years) took the powder as an opaque

capsule. The viability of the probiotic was tested monthly. Both

subjects and investigators were blind to the treatment groups. Study

duration was 12 weeks, followed by a 7 month observational phase to

observe disease manifestations. There were five scheduled visits: 2

weeks before starting the treatment (visit 0), at the beginning of the

treatment (visit 1), then 4 weeks (visit 2), 8 weeks (visit 3), and 12

weeks (visit 4) after treatment was initiated. Parents received two

phone calls during the treatment period to check on patient progress and

compliance (6 and 9 weeks after the beginning of the treatment). At each

visit the severity of the child’s AR was evaluated using the specific

symptoms scores (SSS) and symptom medication scores (SMS) [14,15].

All parents completed a questionnaire (visit 0) about

AR and the allergic disease history of their child, the family’s history

of allergic diseases, and any current oral or topical medication

currently in use. During the 12 week study parents were asked to

complete a weekly diary of medication use, health problems, and the

presence and severity of AR in the child to aid recall for the

questionnaire at the study visits. A final questionnaire was completed

at the last office visit, which included previous medication usage,

other allergic diseases, and changes in life style or housing during the

study.

Both the treated and UT patients maintained a weekly

diary of allergic symptoms during the antigen exposure period. Specific

symptoms scores (SSS) were recorded for nasal blockage, nasal itching,

sneezing, rhinorrhea, eye irritation and watering, wheezing, cough, and

asthma. Symptom medication scores (SMS) were calculated from patient

diaries, as described previously [14,15]. During the study, all patients

received same medications in the whole period according to individual

allergic status and allowed to take the following medications if

required. Scores were calculated based on drugs used (0.5 points for

each dose of nasal corticosteroids and 2 points for each dose of

antihistamine). Patients were instructed to use local steroids plus

antihistamines only if their symptoms did not improve. Patients were

also asked to report each administration or variation of the initial

drug therapy in the diary. Patients were also instructed to stop their

medication at least 7 days before blood sampling. At each time point

(visit 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4) of the study, a patient self-evaluation was

completed. Each patient was also asked for his/her overall evaluation of

the treatment based on categories of symptoms gravity.

Blood samples were taken before and after treatment,

to examine total IgE, peripheral blood cell counts, and blood eosinophil

counts.

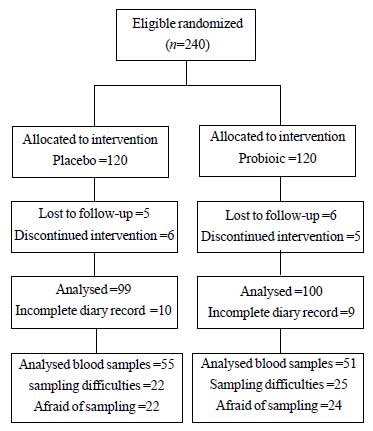

Of the 240 randomized patients, 21 from the probiotic

group and 20 from the placebo group did not complete the study and

another 106 patients (44 probiotic and 49 placebo) dropped out of the

blood trial due to sampling difficulties and withdrawal of consent.

Fig. 1 shows the relevant patient flow chart.

|

|

Fig.1 CONSORT diagram of the study.

|

Statistical analysis: Statistical analysis was

performed using paired and unpaired Student’s t-tests, as appropriate. A

p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All

analyses utilized SPSS 13.0 Statistical Software.

Results

A total of 240 (120 boys) age-matched

Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus (Dp), Dermatophagoides farinae

(Df), or dust-sensitive patients with perennial rhinitis and/or rhinitis

plus mild asthma were recruited from February to March 2009. The

two groups did not differ in terms of demographic variables, age, body

weight, gender, family history, medication scores, and allergic

symptoms. A total of 199 out of the 240 enrolled patients (82.9%)

completed the study in the year 2009. All patients were included in the

safety analysis. The demographic information is shown in Table

I.

TABLE I Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population

|

|

Placebo |

Probiotics groups |

|

N=100 |

N=99 |

|

Age (y) |

8.0 (2.1) |

8.0 (1.9) |

|

Body weight (kg) |

27.6 (4.3) |

27.0 (4.9) |

|

Gender (M/F) |

63/37 |

59/40 |

|

*Family history n

|

64

|

70

|

|

Rhinitis alone, n

|

51 |

52 |

|

Rhinitis + asthma, n |

48 |

46 |

|

Duration of disease (y) |

3.8 (0.5) |

3.8 (0.3) |

|

Mean Specific eye scores |

4.1 (0.9) |

4.3 (0.8) |

|

Mean Specific nasal scores |

8.8 (1.1) |

8.7 (1.2) |

|

Mean Specific lung scores |

8.3 (1.2) |

8.2 (1.1) |

|

Drug scores |

2.8 (1.5) |

2.9 (1.6) |

|

WBC (103/mm3) |

8.64 (2.8) |

8.49 (2.5) |

|

Eosinophils (%) |

5.36 (4.1) |

4.87 (3.8) |

|

IgE (IU/mL) |

543.38 (154.2) |

572.07 (153.2) |

|

Values are mean (SD) unless

indicated; *of allergic disease. |

Results for the three-month follow-up were based on

the patient self-evaluation scores obtained at treatment onset and after

4, 8, and 12 weeks of treatment. Study duration was 12 weeks, followed

by a 7 month observational phase to observe disease manifestations. The

SSS of Lactobacillus salivarius-treated at 8 and 12 weeks were

significantly reduced in comparison with those UT patients, specifically

for eye and nose symptom scores (eye scores: 1.0 ± _–0.5

vs. 2.4 ± –0.9 at 8 weeks and 0.6 ± –0.3 vs. 2.1 ± –0.7 at 12 weeks,

P=0.001 and 0.000; nasal scores: 5.1 ± –0.9 vs

6.5 ± –1.2 at 8 weeks and 3.1 ± –0.8 vs 5.1 ± –1.5 at 12 weeks,

P=0.001 and 0.000) (Table II a, b).

In Lactobacillus salivarius-treated patients a significant

reduction in lung SSS was not observed (Table II c). The

effect of probiotics on drug use was determined by analyzing the drug

score for allergic disease at visit 1, 2, 3, and 4. There was a

statistically significant change in medication scores for rhinitis at

visit 4 between the Lactobacillus salivarius-treated group and UT

group (2.4±_0.9 vs. 2.8 ±_1.1 , P=0.006) (Table II d).

TABLE II Specific Symptom- and Drug-Scores

|

Visit

|

Placebo |

Probiotics group |

P value |

|

Specific eye symptom scores |

|

|

|

|

1 |

4.1 (0.9) |

4.0 (0.8) |

0.262 |

|

2 |

3.0 (0.7) |

3.2 (0.9) |

0.125 |

|

3 |

2.4 (0.90) |

1.0 (0.5) |

0.001* |

|

4 |

2.1 (0.70) |

0.6 (0.3) |

0.000* |

|

Specific Nasal Symptom Scores

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

8.8 (1.1) |

8.7 (1.2) |

0.583 |

|

2 |

5.8 (2.2) |

5.1 (1.5) |

0.052 |

|

3 |

6.5 (1.2) |

5.1 (0.9) |

0.001* |

|

4 |

5.1 (1.5) |

3.1 (0.) |

0.000* |

|

Specific Lung Symptom Scores

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

8.3 (1.2) |

8.2 (1.1) |

0.363 |

|

2 |

3.5 (0.9) |

3.5 (1.0) |

0.885 |

|

3 |

2.3 (0.7) |

2.2 (0.5) |

0.236 |

|

4 |

2.4 (1.4) |

2.1 (0.5) |

0.06 |

|

Specific Medication Scores

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

2.8 (1.5) |

2.9 (1.6) |

0.769 |

|

2 |

2.7 (0.6) |

2.6 (0.5) |

0.737 |

|

3 |

2.9 (1.0) |

2.6 (0.8) |

0.083 |

|

4 |

2.8 (1.1) |

2.4 (0.9) |

0.006* |

|

There were four scheduled visits: at the beginning of the

treatment (visit 1), then 4 weeks (visit 2), 8 weeks (visit 3)

and 12 weeks (visit 4) after starting the treatment. All values

in mean (SD). * p<0.05 (Probiotics vs placebo group at each

visit).

|

Due to sampling difficulties, blood was only

collected from 106 patients (44.2%). There was no difference between the

groups in blood and immunologic profile level before the study.

Blood cell counts, total IgE, and blood eosinophil counts were not

statistically different between visit 4 and 1 in Lactobacillus

salivarius-treated or UT groups (Table III).

TABLE III Immunologic and Blood Cell Parameters

|

Group |

Variable |

visit 1 to visit 4 |

|

Mean difference (SD) |

|

|

|

Placebo (n=51) |

WBC |

1.14 |

(2.60) |

|

Eosinophil |

-0.93 |

(4.27) |

|

IgE |

-150.5 |

(632.76) |

|

Probiotics (n=55) |

WBC |

1.05 |

(2.11) |

|

Eosinophil |

0.72 |

(4.54) |

|

|

IgE |

40.34 |

(392.55) |

|

P value >0.05 for all comparisions

(visit 1 vs visit 4) |

Discussion

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of

a probiotic on the clinical response to allergens in Dp, Df or

dust-sensitive patients. To the best of our knowledge, there have been

no published double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials

examining the effect of Lactobacillus salivarius on atopic

disease in patients with rhinitis. The major results, indicating the

efficacy of Lactobacillus salivarius treatment, was the reduction

in rhinitis symptoms and drug scores. We had also performed a study to

determine the clinical significance. Most healthy children did not

experience any medicine problem related to allergic symptoms, and nasal

and ocular SSS of the healthy participants were similar to the

Lactobacillus salivarius-treated patients’ at 8 or 12 weeks (data

not shown). Taken together, these observations shows that subjective

symptoms are good parameters to assess the condition of allergic

rhinitis. Even though a significant dropout rate (17.1%) was observed in

the current study, the mean values for SSS and SMS in the remaining

group members were similar to those of patients who dropped out. When

examined after 3 months of probiotic treatment, the Lactobacillus

salivarius-treated group reported reduced nasal and eye symptoms

compared with the UT group.

The currently reported findings are compatible with

previously published in vitro results [16-18]. The consumption of

Lactobacillus salivarius strains induces a significant increase

in IL-10 production. IL-10 cytokine can downregulate the production of

Th1 cytokines and induce the development of regulatory T cells [19, 20].

Therefore, the Lactobacillus salivarius strain acts as an immuno-modulator

with anti-inflammatory effects in the regulation of the response to

antigen challenge in allergic disease.

No difference was found in specific immune and blood

parameters between the probiotic and placebo group. This result is in

line with previous studies [21-23]. Several studies have indicated that

T-regulatory cells play an important role in regulating

allergen-specific inflammatory responses. CD4+

CD25+ Foxp3+

cells are recruited into both lungs and draining lymph nodes and can

suppress allergen-induced mucous hypersecretion, airway eosinophilia and

hyperresponsiveness [24-27]. In addition, the natural resolution of an

allergic airway response to Der p1 in mice was shown to be dependent on

CD4+ CD25+

Foxp3+ cells that appear in

the lungs and drain mediastinal lymph nodes following an airway

challenge. Recently, studies revealed that L. salivarius AH102

did not alter T-regulatory cell number in animal model tested [28]. The

exact mechanism for the effects of this strain of probiotics on the

regulatory mechanisms of the immune responses in humans is not as yet

clearly defined. Further studies are needed to clarify this point.

In conclusion, we found that a marked reduction of

the symptom scores was observed during treatment with Lactobacillus

salivarius, with differences in anti-allergic drug intake in

patients. The magnitude of the reduced symptom scores is a clinically

important issue to investigate the application of probiotics.

Funding: Supported by grants from Hualien Tzu-chi

Hospital; Competing interests: None stated.

References

1. Kao CC, Huang JL, Ou LS, See LC. The prevalence,

severity and seasonal variations of asthma, rhinitis and eczema in

Taiwanese schoolchildren. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2005;16:408-15.

2. Krishna MT, Mavroleon G, Holgate ST. Essentials of

Allergy. London: Martin Dunitz; 2001: 107-27.

3. Havenaar R, Huis in’t Veld JHJ. Probiotics: a

general view. The lactic acid bacteria. In: Wood BJB, Ed. The

Lactic Acid Bacteria in Health and Disease. London: Elsevier Applied

Science. 1992;1:151–71.

4. Bjorksten B, Naaber P, Sepp E, Mikelsaar M. The

intestinal microflora in alergic Estonian and Swedish 2-year-old

children. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;29:342-6.

5. Kirjavainen P, Arvola T, Salminen S, Isolauri E.

Aberrant composition of gut microbiota of allergic infant: a target of

bifidobacterial therapy at weaning. Gut. 2002;51:51-5.

6. Pike MG, Heddle RJ, Boulton P, Turner MW, Atherton

DJ. Increased intestinal permeability in atopic eczema. J Invest

Dermatol. 1986;86:101-4.

7. Isolauri E, Arvola T, Sutas Y, Moilanen E,

Salminen S. Probiotics in the management of atopic eczema. Clin Exp

Allergy. 2000;30:1604-10.

8. Rosenfeldt V, Benfeldt E, Nielsen SD, Michaelsen

KF, Jeppesen DL, Valerius NH, et al. Effect of probiotic

Lactobacillus strains in children with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin

Immunol. 2003;111:389-95.

9. Peng GC, Hsu CH. The efficacy and safety of

heat-killed Lactobacillus paracasei for treatment of perennialallergic

rhinitis induced by house-dust mite. Pediatr Allergy Immunol.

2005;16:433-8.

10. Wang MF, Lin HC, Wang YY, Hsu CH. Treatment of

perennial allergic rhinitis with lactic acid bacteria. Pediatr Allergy

Immunol. 2004;15:152-8.

11. Ciprandi G, Vizzaccaro A, Cirillo I, Tosca A.

Bacillus clausii effects in children with allergic rhinitis. Allergy.

2005;60:702-10

12. Aldinucci C, Bellussi L, Monciatti G, Passŕli GC,

Salerni L, Passŕli D, et al. Effects of dietary yoghurt on

immunological and clinical parameters of rhinopathic patients. Eur J

Clin Nutr. 2002;56:1155-61

13. Li CY, Lin HC, Hsueh KC, Wu SF, Fang SH. Oral

administration of Lactobacillus salivarius inhibits the allergic airway

response in mice Can J Microbiol. 2010;56:373-9.

14. La Rosa M, Ranno C, Andrč C, Carat F, Tosca MA,

Canonica GW. Double-blind placebo-controlled evaluation of

sublingual-swallow immunotherapy with standardizaed Parietaria Judaica

extract in children with allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. J Allergy Clin

Immunol. 1999;104:425-32.

15. Cosmi L, Santarlasci V, Angeli R, Liotta F, Maggi

L, Frosali F, et al. Sublingual immunotherapy with

Dermatophagoides monomeric allergoid down-regulates allergen-specific

immunoglobulin E and increases both interferon-g- and

interleukin-10-production. Clin Exp Allergy. 2006; 36:261-72.

16. Niers LE, Hoekstra MO, Timmerman HM, van Uden NO,

de Graaf PM, Smits HH, et al. Selection of probiotic bacteria for

prevention of allergic diseases: immunomodulation of neonatal dendritic

cells. Clin Exp Immuno. 2007;149:344-52.

17. Di´az-Ropero MP, Marti´n R, Sierra S, Lara-Villoslada

F, Rodríguez JM, Xaus J, et al. Two Lactobacillus strains,

isolated from breast milk, differently modulate the immune response. J

Appl Microbiol. 2007;102:337-43.

18. Drago L, Nicola L, Iemoli E, Banfi G, De Vecchi

E. Strain-dependent release of cytokines modulated by Lactobacillus

salivarius human isolates in an in vitro model. BMC Res Notes.

2010;3:44.

19. D’Andrea A, Aste-Amezaga M, Valiante NM, Ma X,

Kubin M, Trinchieri G. Interleukin 10 (IL-10) inhibits human lymphocyte

interferon gamma-production by suppressing natural killer cell

stimulatory factor/IL-12 synthesis in accessory cells. J Exp Med.

1993;178: 1041-8.

20. Groux H, Bigler M, de Vries JE, Roncarolo MG.

Interleukin-10 induces a long-term antigen-specific anergic state in

human CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1996;184:19-29.

21. Ishida Y, Nakamura F, Kanzato H, Sawada D,

Yamamoto N, Kagata H, et al. Effect of milk fermented with

Lactobacillus acidophilus strain L-92 on symptoms of Japanese cedar

pollen allergy: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Biosci Biotechnol

Biochem. 2005;69:1652-60.

22. Tamura M, Shikina T, Morihana T, Hayama M,

Kajimoto O, Sakamoto A, et al. Effects of probiotics on allergic

rhinitis induced by Japanese cedar pollen: randomized double-blind,

placebo-controlled clinical trial. Int Arch Allergy Immunol.

2007;143:75-82.

23. Xiao JZ, Kondo S, Yanagisawa N, Takahashi N,

Odamaki T, Iwabuchi N, et al. Effect of probiotic Bifidobacteriu

mlongum BB536 in relieving clinical symptoms and modulating plasma

cytokine levels of Japanese cedar pollinosis during the pollen season: a

randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Investig Allergol

Clin Immunol. 2006;16:86-93.

24. Leech MD, Benson RA, De Vries A, Fitch PM, Howie

SE. Resolution of Der p1-induced allergic airway inflammation is

dependent on CD4+ CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory cells. J Immunol.

2007;179:7050-8.

25. McGlade JP, Gorman S, Zosky GR, Larcombe AN, Sly

PD, Finlay-Jones JJ, et al. Suppression of the asthmatic

phenotype by ultraviolet b-induced, antigen-specific regulatory cells.

Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37:1267-76.

26. Strickland DH, Stumbles PA, Zosky GR, Subrata LS,

Thomas JA, Turner DJ, et al. Reversal of airway

hyperresponsiveness by induction of airway mucosal CD4+ CD25+regulatory

T cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2649-60.

27. Wu K, Bi Y, Sun K, Xia J, Wang Y, Wang C.

Suppression of allergic inflammation by allergen-DNA-modified dendritic

cells depends on the induction of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Scand J

Immunol. 2008;67:140-51.

28. Lyons A, O’Mahony D, O’Brien F, MacSharry J,

Sheil B, Ceddia M, et al. Bacterial strain-specific induction of

Foxp3+ T regulatory cells is protective in murine allergy models. Clin

Exp Allergy. 2010;40:811-9.

|

|

|