|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2012;49: 17-19

|

|

Effectiveness of Muskaan Ek Abhiyan

(The Smile Campaign) for Strengthening Routine

Immunization in Bihar, India

|

|

Sonu Goel, *Vishal Dogra, †Satish

Kumar Gupta, PVM Lakshmi, $Sherin

Varkey, $Narottam Pradhan,

Gopal

Krishna and Rajesh Kumar

From the Departments of Health Management, School of

Public Health, PGIMER, Chandigarh; *International Clinical Epidemiology

Network (INCLEN), New Delhi; (Immunization), †UNICEF Office, New Delhi;

$Bihar State UNICEF Office, and

Government of Bihar, Patna.

Correspondence to: Dr Sonu Goel, Assistant Professor

of Health Management, School of Public Health, PGIMER,

Chandigarh 160 012, India.

Email: [email protected].

Received: April 28, 2010;

Initial review: May 13, 2010;

Accepted: October 27, 2010.

Published

online: 2011 March 15.

PII: S097475591000354-1

|

Background: In Bihar State, proportion of fully immunized children

was only 19% in Coverage Evaluation Survey of 2005. In October 2007, a

special campaign called Muskaan Ek Abhiyan (The Smile Campaign)

was launched under National Rural Health Mission to give a fillip to the

immunization program.

Objectives: To evaluate improvement in the

performance and coverage of the Routine Immunization Program consequent

to the launch of Muskaan Ek Abhiyan

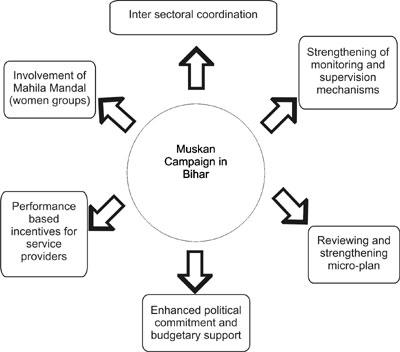

Intervention: The main strategies of the

Muskaan campaign were reviewing and strengthening immunization

micro-plans, enhanced inter-sectoral coordination between the

Departments of Health, and Women and Child Development, increased

involvement of women groups in awareness generation, enhanced political

commitment and budgetary support, strengthening of monitoring and

supervision mechanisms, and provision of performance based incentive to

service providers.

Methods: Immunization Coverage Evaluation Surveys

conducted in various states of India during 2005 and 2009 were used for

evaluation of the effect of Muskaan campaign by measuring the

increase in immunization coverage in Bihar in comparison to other

Empowered Action Group (EAG) states using the difference-in-difference

method. Interviews of the key stakeholders were also done to

substantiate the findings.

Results: The proportion of fully immunized 12-23

month old children in Bihar has increased significantly from 19% in 2005

to 49% in 2009. The coverage of BCG also increased significantly from

52.8% to 82.3%, DPT-3 from 36.5 to 59.3%, OPV-3 from 27.1% to 61.6% and

measles from 28.4 to 58.2%. In comparison to other states, the coverage

of fully immunized children increased significantly from 16 to 26% in

Bihar.

Conclusions: There was a marked improvement in

immunization coverage after the launch of the Campaign in Bihar.

Therefore, best practices of the Campaign may be replicated in other

areas where full immunization coverage is low.

Key words: Evaluation, Immunization, India, Inter-sectoral

coordination, Performance-based incentives.

|

|

Bihar had the second largest

pool of susceptible children in India in year 2001 and routine

immunization (RI) rates have been substantially below national average

[1]. Fully immunized children in the 12-23 months age group was 11.6% in

NFHS-2 and 32.8% in NFHS-3 [2,3]. In eleven districts of the state,

immunization coverage in fact had declined in 2002-04 (DLHS-2) [4]

compared to 1998-2000 (DLHS-1) [5]. Coverage of BCG was 36% in NFHS-2

indicating poor access to immunization services [2]. These findings

indicated a strong need to focus greater efforts on strengthening

immunization in the state. Therefore, Health and Family Welfare

Department of Government of Bihar with the support of Bihar State Office

of UNICEF launched a special campaign in October 2007 called Muskaan

Ek Abhiyan (The Smile Campaign) to give a major fillip to the RI

program. The aim of this study was to evaluate improvement in the

performance and coverage of the Routine Immunization programme

consequent to the launch of Muskaan Ek Abhiyan.

Methods

This observational study was conducted by collecting

program data retrospectively to measure the impact of a package of

interventions implemented under the Muskaan Ek Abhiyan

campaign in Bihar, which were over and above the ongoing routine program

efforts. The study design involved comparison of the immunization

coverage before and after the launch of Muskaan campaign in Bihar

with other Empowered Action Group (EAG) states in the corresponding

period.

Campaign Interventions

The Campaign was guided by the Plan of Action of

National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) prepared by the Bihar Health

Society with the technical support of UNICEF and the National Polio

Surveillance Project (NPSP) supported by WHO [1]. The goal of the

campaign was to provide timely and safe immunization with all antigens

to all eligible children and pregnant women throughout the state. The

guiding principles of the plan were to increase access by increasing the

number and reach of immunization sessions, decreasing the drop outs,

increasing the demand, improving management, and intensifying

supervision for achieving and sustaining high immunization coverage. The

interventions implemented in the Campaign are detailed in Fig. 1.

|

|

Fig. 1 Interventions during Muskaan

campaign in Bihar.

|

Reviewing and strengthening micro-plans:

Traditionally, Routine Immunization (RI) sessions were held at sub

centers on every Wednesday and in one anganwadi center (AWC) on every

Saturday. The micro plan was revamped and Auxiliary Nurse Midwife (ANM)

also conducted RI sessions on every Friday in 2 to 3 AWCs. In first

phase of Muskaan (October 2007 to August 2009), immunization

sessions were also based at health facilities and AWCs. However, in the

second phase (September 2009 onwards), immunization sessions were also

extended to villages and hamlets where health facility/ AWC’s did not

exist. The revised microplan ensured that all AWCs are covered at least

once every month. Anganwadi workers (AWWs) and Accredited Social Health

Activist (ASHA) of the AWC mobilized the pregnant women and children

using the tracking register. ANMs recorded the service delivered in the

vaccination session on reporting formats, MCH and immunization

registers. After the session, AWW and ASHA updated the tracking

registers on the same day or latest by the next immunization session. In

addition to routine immunization activity, three rounds of special

immunization weeks were carried out throughout the State from December

2006 to April 2007 to reach all vulnerable areas. A special post-flood

catch-up immunization campaign was carried out in the five most flood

affected districts of Bihar following massive floods in year 2007.

Intersectoral co-ordination: Operational strategy

for convergence between Integrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS) and

Health Department was facilitated by joint commitment of the highest

level functionaries in the form of a joint government order which

enforced inter-sectoral coordination. The ANM acted as the team leader

of 5 to 10 AWCs. AWWs and ANMs conducted a time bound cross sectional

house-to-house survey to identify all currently pregnant women and

children in 0–2 year age group. Follow-up surveys were conducted on

monthly basis to identify new pregnancies and newborns. All identified

pregnant women and 0-2 year old children were registered in pregnancy

and newborn tracking registers, respectively. Before each immunization

session, AWW and ASHA conducted mass mobilization activities for

identification and mobilization of eligible children and pregnant women

(based on tracking register) to the immunization site in the village.

Involvement of Mahila Mandals (women groups)

for awareness generation: Mahila Mandal meetings were

organized on third Friday of every month for pregnant women and mothers

of young children to create awareness on issues related to health,

immunization, and nutrition. Initially (2007-08), Rs 150 per month was

allocated per AWC per month for Mahila Mandal meeting expenses,

which was later raised to Rs 250 in 2009. However, this grant was

discontinued in phase-2 as the budget allotted for Mahila Mandal

meetings were tagged with the Village Health and Sanitation Committee

(VHSC) funds.

Performance based incentive to service providers:

In phase-1, incentive of Rs 200 per month each for AWW and ASHA and Rs

150 for ANM was provided for coverage above 90%, and Rs 100 each for AWW

and ASHA and Rs 75 for ANM for 80-90% coverage. For coverage of less

than 60%, explanation were sought in their weekly and monthly review

meetings. Under phase-2, the incentive for AWW and ASHA was Rs 200 each

per session for more than 21 beneficiaries, Rs 150 for 16-20, Rs 100 for

11-15 and Rs 50 for 5-10 beneficiaries. Similarly, the incentive for

vaccinators, i.e., ANM was Rs 100 per session for 15 and more

beneficiaries per session and Rs 50 for 1-15 beneficiaries [1].

Enhanced political commitment and budgetary support:

District Immunization Officers and Medical officer In-charges were

trained at state level; who in-turn trained all health workers in their

respective districts. A system of delivering vaccines at the

immunization site through couriers (a person who delivers and brings

back vaccines from the vaccination site on the same day) was implemented

throughout the state. Alternate vaccinators were proposed to counter the

shortage of ANM in year 2007-08. Alternate vaccinators were paid an

honorarium of Rs 350 per session for up to 4 sessions a month (a maximum

of Rs 1400/- per month). Vacant posts of Medical Officers and ANMs were

filled on contractual basis.

Strengthening of monitoring and supervision mechanism:

Updating and cross verification of beneficiaries was envisaged as a core

component of monitoring wherein 2% of all registers had to be verified

by line supervisors. At the level of primary health centers, an

integrated approach to supportive supervision was adopted by Medical

Officers and Integrated Child Development Scheme officials who randomly

verified immunized beneficiaries using tracking registers to release the

monetary incentives. The percentage of sessions held against those

planned was assessed by monitoring whether the vaccine was lifted from

the storage sites and whether ANM, ASHA and AWW were present at the

vaccination site.

At block level, a steering committee consisting of

Medical Officer In-charge, Child Development Project Officer, Senior

Medical Officer, and Health Manager was formed to facilitate

implementation and monitoring of the campaign related activities. At

district level the campaign was under the control of District Health

Society (DHS). The District Magistrate chaired the meetings of the

District Task Force to review the monthly immunization progress report.

A system of regular monitoring was carried out independently by the

state and district officials of Government of Bihar, UNICEF and

NPSP-WHO. The monitoring feedback was sent to Divisional Commissioners

and Regional Deputy Directors of Health for necessary action. Selective

indicators were reviewed weekly by the Executive Director, NRHM.

Monitoring presentations were made to all District Immunization officers

in monthly meetings. The political leadership also maintained a strong

oversight of all campaign activities.

Performance and Coverage Evaluation

National Family Health Survey (NFHS) [2, 3], Rapid

Household Survey (RHS) [6], Immunization Survey of Bihar (ISB) [7],

District Level Household Surveys (DLHS) [4,5,8], and Coverage Evaluation

Surveys (CES) [9-10], conducted by various agencies that used standard

survey methodology were used for assessment of the immunization

coverage. Super-vision reports were also reviewed to ascertain the

quality of immunization services. Interviews of the key stakeholders in

the state were also conducted to substantiate the findings. The data

collection was done from September to December 2009, and analysis was

done in January and February 2010. Informed consent was obtained from

the Government Officials and UNICEF office of Bihar state.

Results

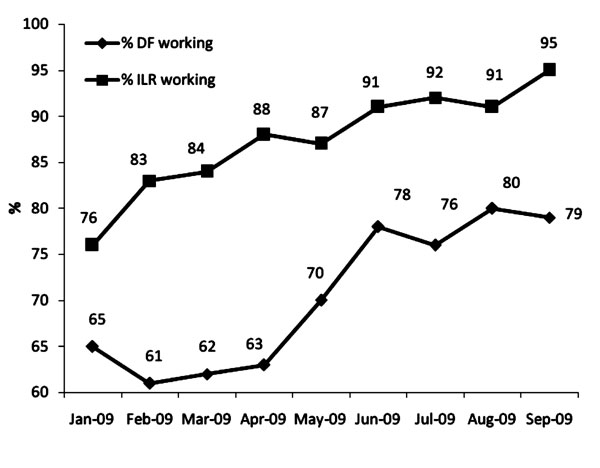

All monitoring indictors related to immunization

performance showed a significant improvement since the launch of the Muskaan

campaign (Table I). It was also found that the

presence of AWW and ASHA workers had increased from 57% and 14% in

2006-07 to 75% and 64% in 2008-09, respectively after the implementation

of the campaign [7]. The functioning of Deep Freezers (DF) and Ice-lined

Refrigerators (ILR) had also improved after the launch of the campaign (Fig.

2). The downtime of various cold chain equipments had decreased

[7].

Table I Monitoring Indicators of Routine Immunization Sessions in Bihar

|

Session indicator |

2005-06 |

2006-07 |

2007-08 |

2008-09 |

|

Sessions held |

91% |

93% |

92% |

91% |

|

Session with |

|

ANM |

91% |

94% |

96% |

95% |

|

ASHA |

0% |

14% |

55% |

64% |

|

AWW |

54% |

57% |

52% |

75% |

|

ANM: Auxiliary Nurse Midwife;

Asha: Accredited Social Health Activitist; AWW: Anganwadi

worker. |

|

|

Fig. 2 Functional status of Deep freezers and

Ice-lined refrigerators at Primary Health Centers in Bihar.

|

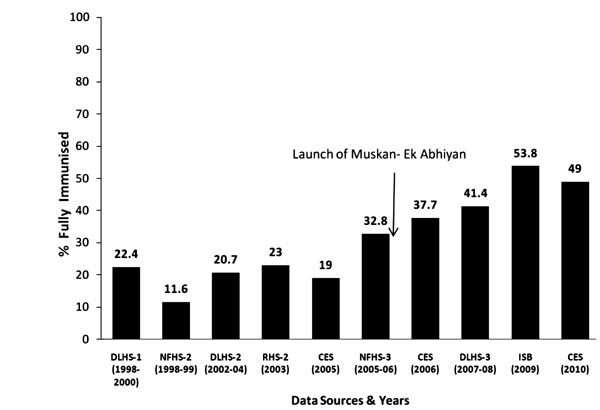

The trend of fully immunized children before and

after the Muskaan campaign is presented in Fig. 3.

The Coverage Evaluation Surveys show that the proportion of fully

immunized children has increased from 19% in 2005 to 49% in 2009 (P<0.001).

The coverage of BCG increased from 52.8% to 82.3% (P<0.001),

DPT-3 from 36.5% to 59.3% (P<0.001), OPV-3 from 27.1% to 61.6% (P<0.001)

and measles vaccine from 28.4% to 58.2% (P<0.001). Between 2005

and 2009, there was a statistically significant improvement (16% to 26%)

in immunization coverage among 12-23 month old children in Bihar as

compared to other EAG states [9,11]

(Table II).

Table II Percentage of Fully Immunized Children (12-23 months) in Empowered Action Group (EAG)

States in Coverage Evaluation Survey 2005 and 2009

| State |

2005a |

2009b |

Difference

d=(b-a) |

*Diff-in-

Diff for Bihar |

| Bihar |

19.0 |

49.0 |

30.0 |

- |

| Chhattisgarh |

44.4 |

57.3 |

12.9 |

17.1 |

| Uttar Pradesh |

33.8 |

40.9 |

7.1 |

22.9 |

| Madhya Pradesh |

38.9 |

42.9 |

4.0 |

26 |

| Orissa |

53.2 |

59.5 |

6.3 |

23.7 |

| Uttaranchal |

61.1 |

71.5 |

10.4 |

19.6 |

| Jharkhand |

45.7 |

59.7 |

14.0 |

16.0 |

| Rajasthan |

49.9 |

53.8 |

3.9 |

26.1 |

*Diff-in-Diff (Difference-in-Difference) = Bihar (column d

first row) – Each State (column d row for each state). It

reflects net increase between 2005 and 2009 in Bihar after

taking into account increase in each of the other states during

the same period; All diff-in-diff were statically significant. |

|

|

NFHS-National Family and Health Survey, DLHS- District Level

Household Survey, CES- Coverage Evaluation Survey,

ISB-Immunization Survey of Bihar, RHS- Rapid Household Survey

Fig. 3 Fully immunized children (12-23

months) in Bihar.

|

Discussion

The proportion of fully immunized children increased

almost two and a half times after the launch of Muskaan campaign.

Antigen-wise coverage indicates that nearly two third children are being

vaccinated against DPT-3 and measles in Bihar. Several factors such as

the launch of NRHM which has brought additional funding and human

resources (such as ASHAs) may have contributed to this positive change;

however, the package of inter-ventions implemented under the Muskaan

campaign seem to be a key factor behind such positive impact as the

improvements in Bihar were 16 to 26% higher than other EAG states where

NRHM inputs were available over the same time period.

A study in district Yamunanagar in Haryana reported

significant increase in age appropriate immunization coverage with

involvement of Community Health workers and vaccinators, revamping of

micro plans and regular monitoring [11]. It has also been shown in

Indonesia that only training the health workers is not sufficient for

effective routine immunization, but the guidance provided through

supportive supervision has helped in improving various aspects of

immunization such as logistics recording, cold chain management, stock

management, vaccine management and reporting and recording [12]. In this

study also, the supportive supervision mechanism may have helped to

identify the areas of continued weakness which need further on job

training and supervision. Integrated efforts of ICDS and health

department at all levels especially revision of micro plans and hiring

of additional ANMs along with additional day for immunization may have

helped to increase the overall immunization coverage in Bihar. Moreover,

a meticulously planned ‘coverage based incentive’ strategy might also

have worked to increase immunization coverage in Bihar, as it inculcated

a motivation among the service providers and mobilizers at the grass

root level. A global review of performance based incentives by Eichler,

et al. [13]. showed that incentivizing will be effective only

when there is careful planning, implementation, monitoring and

supervision [13]. Muskaan strategy has given importance to all

the components of immunization starting from the planning,

implementation, monitoring and supervision along with provision of

performance based incentives, and political commitment.

The main area of concern has always been to reduce

‘left-outs’ and ‘drop-outs’, which was addressed by tracking registers

and ‘immunization due’ list maintained at sub centre level. In Bihar,

the number of drop-outs and left-outs has decreased since the launch of

Muskaan campaign. It has been observed that improving health

facility practices can increase immunization coverage through reducing

"drop-outs" and "missed opportunities". In Ethiopia, the use of reminder

stickers for parents resulted in nearly 50% decrease in dropout between

DPT1 and DPT3 [14]. The introduction of electronic immunization registry

and tracking system in Rajshahi City Corporation in Bangladesh has

helped in the planning and execution of effective immunization at an

operational level by providing a back-up even if parents forget their

child’s vaccination dates, guiding health workers towards those who need

their doses, and potentially reducing vaccine wastage [15].

Link workers involved as mobilizers encouraged people

to seek immunization services, which were brought closer to the

communities. In our study, the presence of AWW and ASHA workers had

increased after the implementation of the Muskaan campaign.

Similar findings were observed in Bangladesh, where semiliterate and

illiterate local women employed in an urban setting to track defaulters,

to refer them to services and accompany mothers to immunization clinics

has improved immunization coverage rates [16]. In Kenya, school

buildings were utilized as immunization centers, with schoolchildren

circulating immunization information within their communities [17]. In

Nigeria, access to immunization services was improved by increasing the

number of locations offering immunization and adding mobile clinics in

the evenings [18].

It is difficult to extract the effect of individual

interventions of Muskaan campaign. Prospective studies are

required to measure the effect of each intervention; however, it is

often difficult to conduct such studies in program settings. About half

of the children still remain to be immunized against various antigens in

Bihar, and selective use of specific interventions in different district

may reveal the effect of different interventions on the coverage.

Overall, the strategies employed under

Muskaan

campaign seem to be successful in most parts of the state. A key

strength of the model appears to be that the interventions were directed

through existing public health system frontline providers. Improvement

in availability of skilled human resources, quality of microplans,

review of Muskaan registers by supervisors, timely disbursement

of monetary incentives, and inclusion of urban area in micro planning

can further improve immunization coverage in Bihar. Although a sound

supervision mechanism is in place in Bihar, it needs to be sustained in

future as well, since the Muskaan Campaign was very much

dependent on support of partner organizations. A downward trend in

immunization coverage rates was observed in DLHS 2 (2002-04) [4] and in

CES 2009 as well, hence, in-depth review of causes of such reversal

should be looked into so as to sustain the gains in the longer term.

References

1. Bihar State Health Society. Strengthening

Routine Immunizations- Bihar State Action Plan for Routine

Immunization 2005-2010. Available from:

http//statehealthsocietybihar.org/SHS. Accessed on July 16, 2010.

2. International Institute for Population

Sciences (IIPS) and ORC Macro. National Family Health Survey

(NFHS-2). Available from http://www.nfhsindia.org/india2.html.

Accessed on July 16, 2010.

3. International Institute for Population

Sciences (IIPS) and ORC Macro. National Family Health Survey

(NFHS-3). Available from http://mohfw.nic.in/nfhsfactsheet.htm.

Accessed on July 16, 2010.

4. International Institute for Population

Sciences (IIPS). District Level Household and Facility

Survey-2(2002-04). Available from:

http://www.rchiips.org/PRCH-2.html. Accessed on July 16, 2010.

5. International Institute for Population

Sciences (IIPS). District Level Household and Facility

Survey-1(1998-99). Available from:

http://www.rchiips.org/PRCH-1.html. Accessed on July 16, 2010.

6. International Institute for Population

Sciences (IIPS). Rapid Household Survey, Phase-1, under Reproductive

and Child Health Project - India. Mumbai: IIPS, 2000.

7. Immunization Survey of Bihar. Formative

Research and Development Services 2008-09. Available from:

http//www.mohfw.nic.in/NRHM/PIP10_11/Bihar.pps. Accessed on July 16,

2010.

8. International Institute for Population

Sciences (IIPS). District Level Household and Facility Survey-3

(2007-08). Available from: http://www.rchiips.org/ARCH-3.html.

Accessed on July 16, 2010.

9. UNICEF. Review of National Immunization

Coverage. Coverage Evaluation Survey-2005. Available from:

http://www.unicef.org/india/Coverage_Evaluation_Survey_ 2005.pdf.

Accessed on August 10, 2010.

10. UNICEF. Review of National Immunization

Coverage. Coverage Evaluation Survey-2006. Available from:

http://www.unicef.org/india/Coverage_Evaluation_Survey_ 2006.pdf.

Accessed on August 16. 2010.

11. Prinja S, Gupta M, Singh A, Kumar R.

Effectiveness of planning and management interventions for improving

age appropriate immunization in rural India. Bull WHO.

2010;88:97-103.

12. Supportive supervision to sustain health

worker capacity in Nanggroe Aceh Darussalam and North Sumatera.

Available from: http://www.path.org/files/CP _Indonesia_

supp_sprvsn_aceh_fs.pdf. Accessed on April 10, 2010.

13. Eichler R, Levine R. Performance initiatives

for Global health: Potential and Pit Falls. Center for Global

Development Brief. May 2009. Available from:

http//www.festmih.eu/document/1757. Accessed on April 10, 2010.

14. Berhane Y, Pickering J. Are reminder stickers

effective in reducing immunization dropout rates in Addis Ababa,

Ethiopia? J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;96:139-45.

15. Ahmed M. Electronic Immunisation Registry and

Tracking System in Bangladesh. e- Government for Development -

eHealth Case Study. Available from: http://www.

egov4dev.org/health/case/banglaimmune.shtml. Accessed on April 14,

2010.

16. Hughart N, Silimperi DR, Khatun J, Stanton B.

A new EPI strategy to reach high risk urban children in Bangladesh:

urban volunteers. Trop Geogr Med. 1992;44:142-8.

17. Expanded Programme on Immunization: Study of

feasibility, coverage and cost of maintenance immunization for

children by district mobile teams in Kenya. Weekly Epidemiol Rec.

1977;52:197-204.

18. Oruamabo RS, Okoji GO. Immunisation status of children in Port

Harcourt before and after commencing the Expanded Programme on

Immunisation. Public Health. 1987;101:447-52.

|

|

|

|

|