|

Childhood fever is one of the

commonest reason for medical consultation in

children, being responsible for 15-25% visits in

primary care, and also presentations to the

emergency departments (ED) [1,2], and is known to

cause significant anxiety in parents [3]. Most

children undergo evaluation for at least one febrile

illness before their third birthday [4]. Western

studies report good parental awareness about fever

[5], but studies from India [6,7] have shown

conflicting results. Frequently, parents do not

document temperature or record it improperly,

leading to undue anxiety and over-crowding of the ED

[6-8]. We studied the correlation of temperatures

measured at home by parents with recordings done at

presentation in the ED among infants with acute

illnesses.

This cross-sectional study was

conducted from April, 2018 to January, 2019 at the

pediatric ED of a public hospital in northern India,

after taking clearance from the Institutional Ethics

Committee. Febrile children aged 3 month to 2 year,

with fever of at least 4 days were considered for

enrollment. A febrile child was defined as one with

history of fever e"38ÚC recorded at least once at

home in previous 24 hours. Those suffering for fever

for >7 days, children with any underlying heart

disease, and children with any diagnosed

immunodeficiency disorder or conditions predisposing

to recurrent infections (like type 1 diabetes,

vesico-ureteric reflux) were excluded. Consecutive

children were enrolled on one pre-decided day every

week.

After taking written informed

consent, enrolled children were evaluated clinically

and initial management provided. Subsequently, based

on history, and clinical and laboratory information,

they were treated as inpatient or outpatient. For

all enrolled children, demographic details, contact

information and details of education and income of

parents were collected. History was taken regarding

highest temperature recorded at home and any

associated symptoms, treatment taken if any before

presentation, relevant history of co-morbidities,

immunization and feeding history. Anthropometric

measurements were taken for all included children as

per standard guidelines, and Z-scores were

calculated using Anthrocalc application.

All the data were recorded in a

structured pre-tested form. Rectal temperature was

taken at presentation for all enrolled children, The

various diagnoses were made and management carried

out according to the departmental protocols guided

by standard management guidelines [9,10]. Mean (SD)

or median (IQR) were calculated for the baseline

characteristics. Pearson correlation coefficient was

calculated for temperature documented at home and in

the ED. Comparisons were done between children with

fever documented in ED, and those without fever

documented in ED.

Out of overall study population

of 150 children with history of fever of 4-7 days in

respective age group attending ED, only 108 (68.3%

boys) had documented fever at home. The median (IQR)

age of the study population was 12 (3-20) months.

The median Z scores for all anthropometric variables

(weight, length and head circumference) were greater

than –3. Majority (88%) of children belonged to the

lower middle (III) and upper lower (IV)

socioeconomic classes, and majority of mothers (62%)

had at least secondary school education (Table

I). Along with fever, the most common

presenting complaint was respiratory problems.

Table I. Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population (N=108)

| Characteristics |

No. (%) |

| Weight, Z-score# |

-2.05 (4.62) |

| Height, Z-score# |

-1.525 (2.57) |

| HC, Z-score# |

-1.66 (1.64) |

|

Immunization statusa |

|

| Partially immunized |

9 (8.3) |

| Fully immunized |

78 (72.2) |

|

Socioeconomic statusb |

|

| Upper middle class |

13 (12) |

| Lower middle class |

51 (47.2) |

| Upper lower class |

42 (38.8) |

| Lower class |

2 (1.9) |

| Maternal education |

|

| Illiterate |

24 (22.2) |

| Primary school |

17 (15.7) |

| Secondary school |

56 (51.9) |

| Graduate |

11 (10.1) |

|

HC: Head circumference; bModified Kuppuswamy

socioeconomic status scale for year 2018.

aImmunization details not known. |

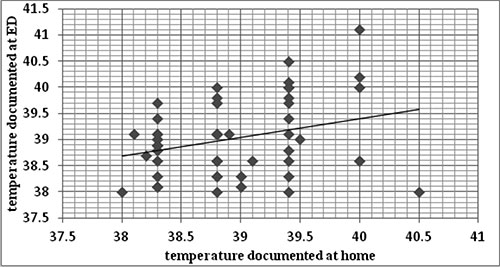

Of the children for whom fever

was documented at home, nearly half (46.3%) did not

have fever at presentation in the ED. Mean (SD)

temperatures documented at home and ED were [38.8

(0.16)°C vs 39 (0.7)°C; P=0.03]. Among

those who were febrile in ED, the correlation

coefficient (r) of fever documented at home

and in ED was 0.3 (95% CI, 0 to 0.6), suggesting a

weak correlation of axillary fever documented by

parents at home and that of rectal temperature

documented in ED (Fig. I).

|

|

Fig.1 Correlation

between fever documented at home and in ED

(r=0.3).

|

For five children, rectal

temperature could not be documented in view of their

critical condition at presentation to ED, and

axillary temperature was documented in them so as

not to hinder required resuscitative measures. Of

the illiterate mothers, 42% did not document the

fever as compared to 205 of those with a secondary

school education (P=0.02). There was no

increased risk of having a severe infection if

temperature is documented at ED versus if

fever is not documented at presentation [OR (95%

CI): 0.96 (0.32-2.85); P=0.94].

In our study majority of parents

measured temperature at home by axillary or oral

thermometry, There was a weak correlation between

axillary/ oral temperature measured at home and

rectal temperature documented at ED. Findings in our

study are in agreement with the internet-based

survey done by de Bont, et al. [5] in

Netherlands, which showed 71.5% parents document

fever if their child is ill, although majority

documented rectal temperature. None of the parents

in our study documented rectal temperature, as home

measurement of rectal temperature by parents is

uncommon in Indian settings. Other studies from

hospitals in various regions in India report

conflicting results on proportion measuring

temperature of febrile children at home (14.5-71%)

[6,7]. These differences may be based on regional

socio-cultural factors. The finding of association

of temperature documentation at home with higher

educational level of mother is in agreement with

previous reports [8].

The small sample size in our

study may be a limiting factor for applying results

of this study to general population. Most of the

children had already received antipyretics before

presenting to ED, and may have been exposed to

varying environmental temperatures while travelling

to hospital; thus explaining the poor correlation

between temperature documented at home and in ED.

Additional analysis could have been done for

temperature correlations in different disease

groups, but the numbers for individual diseases were

less for valid comparisons. Further studies may need

to study the relationship of domiciliary temperature

measurements and fever at presentation, as triage

and evaluation of pediatric patients in crowded EDs

is frequently dependent on the presence/absence of

fever.

Ethics clearance:

Institutional ethics committee of MAM College; No.

17/IEC/MAMC/2017/Peds/07 dated 10 October, 2017.

Contributors: PP: subject

assessment, management under supervision, data

analysis, and preparing first draft of manuscript;

RB: important contribution in study concept, data

analysis and manuscript preparation; DM: Study

concept, supervision and finalization of manuscript.

All authors approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests: None

stated; Funding: None.

REFERENCES

1. Muth M, Statler J, Gentile DL,

Hagle ME. Frequency of fever in pediatric patients

presenting to the emergency department with

non-illness-related conditions. J Emerg Nurs.

2013;39:389-92.

2. Sands R, Shanmugavadivel D,

Stephenson T, Wood D. Medical problems presenting to

paediatric emergency departments: 10 years on. Emerg

Med J. 2012;29:379-82.

3. Purssell E, Collin J. Fever

phobia: The impact of time and mortality - A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs

Studies. 2016;56:81-9.

4. Finkelstein JA, Christiansen

CL, Platt R. Fever in pediatric primary care:

occurrence, management, and outcomes. Pediatrics.

2000;105:260-6.

5. de Bont EG, Francis NA, Dinant

GJ, Cals JW. Parents’ knowledge, attitudes, and

practice in childhood fever: an internet-based

survey. British J Gen Pract. 2014;64:e10-6.

6. Thota S, Ladiwala N, Sharma

PK, Ganguly E. Fever awareness, management practices

and their correlates among parents of under five

children in urban India. Int J Contemp Pediatr.

2018;5:1368-76.

7. Agrawal RP, Bhatia SS, Kaushik

A, Sharma CM. Perception of fever and management

practices by parents of pediatric patients. Int J

Res Med Sci. 2013;1:397-400.

8. Bertille N, Fournier-Charriere

E, Pons G, Chalumeau M. Managing fever in children:

A national survey of parents’ knowledge and

practices in France. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e83469.

9. Sharma S, Sethi GR, eds.

Standard Treatment Guidelines: A Manual for Medical

Therapeutics. Delhi Society for Promotion of

Rational Use of Drugs & Wolters Kluwer Health, 5th

ed, 2018.

10. Mahajan P, Batra P, Thakur N, et al.

Consensus Guidelines on Evaluation and Management of

the Febrile Child Presenting to the Emergency

Department in India. Indian Pediatr. 2017;54:

652-60.

|