|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2020;57:

1110-1113 |

|

Pediatric Liver Transplantation in India: 22

Years and Counting

|

|

Smita Malhotra, 1 Anupam

Sibal1

and Neerav Goyal2

From 1Department of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Hepatology and

2Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery Unit, Indraprastha Apollo

Hospitals, New Delhi, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Smita Malhotra, Department of Pediatric

Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Apollo Institute of Pediatric Sciences,

Indraprastha Apollo Hospital, New Delhi, India.

Email:

[email protected]

|

|

Liver transplantation in

India has grown exponentially in the last decade with 135

centers now performing between 1500-2000 transplants a year, 10%

of which are pediatric. Survival rate surpassing 90% has been

achieved, and India is now an important regional liver

transplant hub in South and South-East Asia. The indications

have expanded to include increasing number of liver-based

metabolic disorders that may or may not cause liver disease.

Recipients, who were previously considered non-transplantable

such as those with pre-existing portal vein thrombosis, can be

successfully managed with innovative microvascular techniques.

The donor pool has grown with the use of marginal grafts and ABO

incompatible organs. Financial constraints are being overcome by

crowd funding and increasing philanthropic efforts.

Keywords: Deceased donor, History,

Multi-organ transplant, Outcome.

|

|

L iver transplant is curative

for acute liver failure,

chronic end stage liver diseases, some liver

tumors and inborn metabolic errors that may or may not cause liver

disease per se. Advancements in preoperative care,

surgical techniques, intensive care management along with availability

of potent immunosuppressive drugs have helped attain 94% 1-year, 91%

5-year, and 88% 10-year patient survival in pediatric liver transplant

recipients [1]. In India, the first successful pediatric liver

transplant was performed in 1998 [2], and that boy with biliary atresia

is now about to complete his graduation in medicine and is doing well on

minimal immunosuppression (Table I). Every year around

1500-2000 liver transplants are now performed, of which approximately

10% are pediatric. Survival rates sur-passing 90% have since been

attained in India [3-5]. Initial progress was slow as part of a learning

curve with limitations due to scarcity of trained personnel, poor

awareness amongst primary care doctors, reservations regarding donor

safety and the financial implications. By 2007, only 318 liver

transplants had been performed in India [6]. The growth has been

exponential in the last decade; although collated data of the country is

not available. This has been sustained mainly by living donor liver

transplant (LDLT) though deceased donation (DDLT) is picking up,

primarily in the southern part of the country where some centers report

a 70/30 LDLT/DDLT overall distribution [7]. As per the Global

Observatory on Donation and Transplantation, 1945 liver transplants

(adult and pediatric) were performed in India in the year 2018 (1313

LDLT).

Table I History of Pediatric Liver Transplantation in India

| Event |

Year |

| Pediatric living donor liver transplant

(LDLT) |

1998 |

| Adult deceased donation liver

transplant (DDLT) |

1998 |

| Liver transplant for acute liver

failure (ALF) |

1999 |

| Adult combined liver and kidney

transplant |

1999 |

| Pediatric combined liver and kidney

transplant |

2007 |

| Pediatric re-transplant |

2002 |

| Pediatric DDLT |

2007 |

| Liver transplant for HIV |

2008 |

|

Liver transplant for Criggler-Najjar syndrome

|

2008 |

| Domino transplant |

2009 |

| LDLT for factor VII deficiency |

2010 |

| Auxillary liver transplant for

ALF |

2012 |

| ABO incompatible liver transplant |

2014 |

|

Domino auxillary liver transplant |

2015 |

Auxiliary liver transplant (auxiliary partial

orthotopic liver transplant, APOLT) with implantation of a partial graft

without fully removing the native liver is technically more challenging

with a higher complication rate. It is a suitable option for acute liver

failure and metabolic disorders without cirrhosis as it offers a chance

for immunosuppression free life in case of native liver regeneration or

restoration of defective metabolic function with newer therapies.

Successful APOLT for acute liver failure has been reported from India

but the modality has not become popular due to the higher risks involved

with retaining a diseased liver in acute liver failure with its

attendant toxic and metabolic effects.

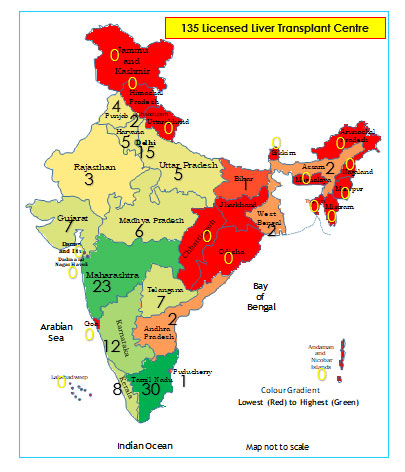

The establishment of a new liver transplant program

requires approval from a regional health body after evaluation of

infrastructure and expertise. As per the National organ and tissue

transplant organisation (NOTTO) there are now about 135 centers for

liver trans-plant in India, including second tier cities apart from the

metros, with majority of the pediatric work limited to about 10 centers

(Fig. 1). As liver transplant is largely private sector

driven and is a high cost procedure, credibility rests on preventing

commercialization of the programs. This has been made feasible by the

stringiest criteria laid down by the government and strict scrutiny by

authorization committees in every case to ensure donation is from a

relative on a wholly voluntary basis with no coercion. In camera

meetings are held and all documents to establish near relationship are

verified before a go ahead is attained even in cases requiring emergency

transplants.

|

|

Fig. 1 Distribution of liver

transplantation centers in India, 2020.

|

A significant proportion of pediatric patients are

from overseas. Patients from about 20 countries have been transplanted

at our center, and also at other Indian centers. A few are partially or

wholly funded by their governments, while many others raise funds

through international charities and/or social organizations. Many

families have gone on to form support groups in their respective

countries. The Indian Human Organ Trans-plant Act, enacted in 1994,

allows foreign nationals to receive a deceased organ in India only if no

suitable Indian recipient is available. As cadaveric donations are few

and the waiting list is long, foreign nationals would only qualify for

LDLT.

India is now an important regional center for liver

transplant in South and South East Asia, more so for pediatric patients.

Many of these neighboring countries have either not yet set up

transplant units or are in the fledgling phase running predominantly

adult programs. Pediatric liver transplant carries its own set of

challenges due to the smaller diameter of vessels requiring greater

surgical expertise along with need for specialized pediatric intensive

care and usually a longer duration of postoperative hospital stay.

Moreover, many of these countries have very few pediatric hepatologists

with expertise in post-transplant care, thus necessitating a thorough

coordination with the transplant unit for follow up once the families

travel back to their native countries.

EXPANDING THE DONOR AND RECIPIENT POOL

Though biliary atresia remains the leading indication

for liver transplant in children [8], improving outcomes have encouraged

expanding indications to include liver-based metabolic defects [9].

Where these defects cause liver damage, liver transplant is curative by

replacing the diseased organ as in other disorders of liver architecture

leading to synthetic dysfunction and decompensation. The other group

includes disorders whereby a genetically inherited enzymatic defect,

wholly or partially liver based with a structurally normal liver, causes

neurological/multiorgan involvement that may be prevented by replacing

the liver. Liver transplant should be performed early before

irreversible damage occurs in target organs. These include Criggler

Najjar syndrome, urea cycle defects and organic acidemias to achieve

intact neuro-logical status, familial hypercholesterolemia to prevent

cardiac disease and/or sudden death, and primary hyperoxaluria where an

early liver transplant prevents renal failure or else a

combined/sequential liver kidney transplant would be required to prevent

systemic oxalate overload and its multiorgan consequences. With the

availability of next generation sequencing (NGS) based tests, precise

and timely genetic diagnosis can now be made and timely therapy

instituted.

Livers from patients with Maple syrup urine disease

(MSUD) and familial hypercholesterolemia may be donated to cirrhotic

patients as they are structurally and functionally normal apart from an

enzyme deficiency, which may be compensated by other body tissues to

sustain function. Such transplants, known as domino transplants, have

been successfully reported from India [10]. As our programs are

primarily living-related, the majority of the donors are parents who are

carriers of the recipients’ metabolic or genetic disorders with

autosomal recessive inheritance. Use of such heterozygous donors has

been debated. Data from the Japanese multicenter registry [11] has

reported that outcome after employing heterozygous donors was excellent

with better long-term survival rate. Portal vein thrombosis (PVT), a

known sequelae of cirrhosis, especially more frequently seen in infants

with biliary atresia due to portal vein hypoplasia, is no longer a

contraindication to liver transplant despite the technical difficulty

and higher risks of post-transplant vascular thrombosis endangering the

graft [12].

Pediatric liver transplant has now progressed beyond

the ABO blood group barrier. ABO incompatible (ABOi) transplants are

being increasingly performed when blood group compatible donor from the

family is not available. Despite concerns about liver graft

regeneration, antibody mediated rejection (AMR), higher incidence of

biliary strictures and sepsis, both pediatric and adult ABOi liver

transplant survival has improved markedly and has become comparable to

ABO-compatible liver transplant with the introduction of rituximab

prophylaxis before transplant [13]. Rituximab and/or other B cell

desensiti-zation strategies including plasmapheresis and IVIg are used

to bring down isoagglutinin titers to less than 1/8 pre liver

transplant. Children younger than 2 years of age may not require these

desensitization therapies as blood group isoagglutinins titers are low

and complement system activation is not robust, thus minimizing the

risks of AMR [14]. ABOi liver transplant grafts in acute liver failure

in infants have thus been used more often as lack of time window for

desensitization strategies may limit use of this modality in older

children and adults with acute liver failure [15]. Most busy centers in

India have successfully performed ABOi transplants since the initial

reports of success in 2014 [16].

Size-matching determined by the graft-to-recipient

weight ratio (GRWR) is a crucial determinant for graft suitability and

ideal ratios of 0.8-1 have been advocated. Many centers now have

experience with small for size grafts and it is acceptable for the GRWR

to be as low as 0.5-0.6 if there are accompanying factors of portal vein

pressure £15

mmHg, middle hepatic vein reconstruction, or young donor age [17]. On

the other hand, large for size grafts are problematic in small infants

due to compro-mised portal venous flow and small abdominal cavity. Use

of reduced mono/bi-segment grafts and delayed abdominal closure using

mesh/skin closure help circum-vent abdominal compartment syndrome [16].

Thus, babies as small as 4-5 kg are now being routinely transplanted at

select centers in India.

Other marginal grafts are increasingly being

accepted. These include older donors in the absence of size mismatch and

severe steatosis, moderately steatotic liver grafts if predominant

pattern is of microsteatosis instead of macrosteatosis, donors with a

BMI ³30 kg/m2

and HBsAg-negative/HBcAb-positive liver grafts in HBsAg negative

recipients with active immunization and post-transplant antiviral

prophylaxis to prevent de novo HBV infection [17]. These

strategies have considerably increased the donor pool for liver

transplant in scenarios hitherto found unsuitable.

PERSISTING CONCERNS

Studies on long term morbidities, effects of immuno-suppression

and quality of life post liver transplant are lacking from our country.

LT requires lower immuno-suppression compared to other organs. Indian

patients have been shown to do well on lower immunosuppression as

infections are more common in our scenario [4,5]. Regimens vary across

different programs but cortico-steroids remain the induction agents of

choice with dual agent regimens including calcineurin inhibitors and

renal sparing mycophenolate for the first year, with the aim to come

down to a single agent by the second year. The desired ideal outcome is

attainment of prope tolerance, i.e., almost immune tolerant state

where the recipient is alive with first allograft with no ongoing

rejection episode on tacrolimus therapy with trough levels less than 3

ng/mL, three years post LT. Studies indicate that almost 20% pediatric

patients may attain such immune tolerance with maximal chances for those

transplanted in infancy [18]. However, the SPLIT database analysis has

revealed that the ideal triad of normal growth, stable allograft

function on single-agent immunosuppression, and an absence of

immunosuppression-related complications is achieved in only about a

third of recipients 10 years after LT [1]. Steroid free protocols using

antibody induction (ATG/basiliximab) along with tacrolimus are not yet

in vogue but steroid-free tacrolimus-based immuno-suppression may result

in an enhancement of graft acceptance in the long term as well as in a

higher proportion of children becoming prope tolerant [19,20].

Lack of a database greatly inhibits accurate analysis

of trends, outcomes and long term results. Non-availability of long

term followup from many recipients from overseas is another

disadvantage. With the formation of the Liver Transplant Society of

India, efforts are on for a national registry, hopefully more data

should be available in the coming years. Low numbers for DDLT,

especially in Northern India, is amongst the foremost immediate concern

that requires intense campaigning and education to change the social

mindset. Encouraging organ donation is the need of the hour.

CHANGING SOCIAL SCENARIO

Perhaps, the most crucial limiting factor in our

country has been the cost of liver transplant. The programs are largely

driven through the private sector, and health care insurance is still

not widely prevalent in our country. Moreover, most insurance companies

do not provide cover for diseases of perinatal onset or genetic etiology.

The advent of crowd funding platforms where strangers come together on

the internet to fund a medical catastrophe for an unknown person is

heart-warming and provides an insight into the social responsibility the

community is prompt to take up when transparency is assured. These

campaigns run on social media with tight timelines ranging from a week

to a month, and at times funds have been raised in a day or two for

emergency transplants. Crowd funding with the support of few

philantrophic organizations and individuals dedicated to funding liver

transplants has thus made transplantation attainable for those with

limited resources. Crowd funding works best for children awaiting

trans-plants, perhaps due to the emotive pull of images and videos of

innocent children struggling to wade off certain death that a transplant

could prevent. The predicament of the parents, one of whom is the organ

donor most of the time, also touches a cord. With this active support of

the community in facilitating transplants for children, liver transplant

seems to have finally come of age in our country.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

High-resolution sequence mapping of DNA variation is

now feasible and liver tissue transcriptional signatures are being

studied to identify candidates likely to achieve tolerance and

withdrawal of immune suppression. Genome wide association studies or NGS

for cytokine genotyping to detect single nucleotide polymorphisms in

cytokine gene promotor regions may help identify recipients at low risk

for rejection.

Meanwhile, expansion of this facility in the public

sector is needed as liver transplant is still not available routinely to

those with limited resources. We wait to realize the dream of DDLT

becoming the primary modality, as it is in the Western countries, by

concerted efforts to promote organ donation.

REFERENCES

1. Ng VL, Alonso EM, Bucuvalas JC, et al., for

Studies of Pediatric Liver Transplantation (SPLIT) Research Group.

Health status of children alive 10 years after pediatric liver

transplantation performed in the US and Canada: Report of the studies of

pediatric liver transplantation experience. J Pediatr. 2012;160:820-26.

2. Poonacha P, Sibal A, Soin AS, Rajashekar MR, Raja-kumari

DV. India’s first successful pediatric liver trans-plant. Indian Pediatr.

2001;38:287-91.

3. Sibal A, Bhatia V, Gupta S. Fifteen years of liver

transplan-tation in India. Indian Pediatr. 2013;50:999-1000.

4. Mohan N, Karkra S, Rastogi A, et al.

Outcome of 200 pediatric living donor liver transplantation in India.

Indian Pediatr. 2017;54:913-19.

5. Sibal A, Malhotra S, Guru FR, et al.

Experience of 100 solid organ transplants over a five year period from

the first successful pediatric multi organ transplant program in India. Pediatr

Transplant. 2014;18:740-5.

6. Kakodkar R, Soin A, Nundy S. Liver transplantation

in India: its evolution, problems and the way forward. Natl Med J India.

2007;20:53-56.

7. Narasimhan G, Kota V, Rela M. Liver

transplantation in India. Liver Transpl. 2016;22:1019-24

8. Malhotra S, Sibal A, Bhatia V, et al.

Living related liver transplantation for biliary atresia in the last 5

years: Experience from the first liver transplant program in India.

Indian J Pediatr. 2015:82:884-9.

9. Mazariegos G, Shneider B, Burton B, et al.

Liver trans-plantation for pediatric metabolic disease. Mol Genet Metab.

2014;111:418-27.

10. Mohan N, Karkra S, Rastogi A, Vohra VK, Soin AS.

Living donor liver transplantation in maple syrup urine disease. Case

series and world’s youngest domino liver donor and recipient. Pediatric

Transplant. 2016;20: 395-400.

11. Kasahara M, Sakamoto S, Horikawa R, et al.

Living donor liver transplantation for pediatric patients with metabolic

disorders: the Japanese multicenter registry. Pediatr Transpl.

2014;18:6-15.

12. Conzen KD, Pomfret EA. Liver transplant in

patients with portal vein thrombosis: medical and surgical requirements.

Liver Transpl. 2017;23:S59-S63.

13. Yamamoto H, Uchida K, Kawabata S, et al.

Feasibility of monotherapy by rituximab without additional

desensiti-zation in ABO-incompatible living-donor liver

trans-plantation. Transplantation. 2018;102:97-104.

14. Honda M, Sugawara Y, Kadohisa M, et al.

Long-term outcomes of ABO-incompatible pediatric living donor liver

transplantation. Transplantation. 2018;102:1702 09.

15. Yamamoto H, Khorsandi SE, Cortes Cerisuelo M, et

al. Outcomes of liver transplantation in small infants. Liver

Transpl. 2019;25:1561-70.

16. Soin AS, Raut V, Mohanka R, et al. Use of

ABO-incom-patible grafts in living donor liver transplantation – First

report from India. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2014;33:72-6.

17. Lan X, Zhang H, Li HY, et al. Feasibility

of using marginal liver grafts in living donor liver

transplantation. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:2441-56.

18. Mazariegos GV, Sindhi R, Thomson AW, Marcos A.

Clinical tolerance following liver transplantation: Long term results

and future prospects. Transpl Immunol. 2007; 17: 114-19.

19. Gras JM, Gerkens S, Beguin C, et al.

Steroid-free, tacro-limus-basiliximab immunosuppression in pediatric

liver transplantation: Clinical and pharmacoeconomic study in 50

children Liver Transpl. 2008;14:469-77.

20. Bourdeaux C, Pire A, Janssen M, et al.

Prope tolerance after pediatric liver transplantation. Pediatr Transpl.

2013; 17:59-64.

|

|

|

|

|