World Health Organization (WHO) added tetanus

toxoid vaccine in its Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) in the year

1974 [1]. Almost 15 year later, by 1989, only a quarter (27%) of

pregnant females were receiving the standard doses of tetanus toxoid

[2]. Year 1990 was initially set as target by WHO to achieve the goal of

neonatal tetanus elimination, defined as less than one case per 1000

live births per year in all districts of a country; it was later

extended to 1995. By the end of 1999, there were 57 countries that had

yet not achieved this goal [3].

In the year 2000, WHO, United Nations Children’s Fund

(UNICEF) and United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) partnered to

re-launch their efforts to achieve the goal of neonatal tetanus

elimination. As neonatal tetanus depends mainly on tetanus immunization

of the mother during pregnancy, the goal of elimination of maternal

tetanus was also added to this initiative which was rechristened

"Maternal and Neonatal Tetanus Elimination Program" (MNTE), and year

2005 was set as the cut-off year to achieve this goal [3]. However, 19

countries are yet to achieve this goal [4]. India was one of the last

few countries to be declared free of maternal and neonatal tetanus on

15th May, 2015 [5].

Historical Background

In 1960, Schlesinger described tetanus as a dangerous

but rare disease [6]. But this ‘rarity’ of tetanus could be due

to its gross under-reporting at that time. Attention to the massive

burden of tetanus was drawn by Matveev and Sergeeva [7]. They reported

that during the years 1945-53 (in the countries in which the incidence

of tetanus was recorded), there were more than 350 000 cases, of which

nearly one-third died [7].

There were several reasons due to which tetanus, more

so neonatal tetanus, had been neglected historically as a health

problem. One of the main reasons could be that majority of cases

occurred in poor and illiterate populations with limited access to

information about health services and essential obstetric care [8]. As

per Bytchenko [9], neonatal tetanus was neglected by the health services

due to its high cost of treatment, poor outcome, and lack of reliable

epidemiological data. Until 1984, neonatal tetanus was still reported

per 100 000 population, clearly indicating failure to recognize tetanus

as a more important cause of mortality in newborns as compared to other

age groups [10]. The hospital data were also misleading about its real

incidence because the infants were either dying at home or failing to

reach the hospital. Traditional attitudes such as considering neonatal

death as a wish of God and isolation of the mother and child in the

post-partum period were other reasons that correct extent of neonatal

tetanus was not known until late.

Tetanus has existed in Asia for centuries without any

reliable statistics pertaining to its prevalence. The Indian Clinical

Research Advisory Committee in 1946 suggested that there was a pressing

need to study the magnitude of the problem of tetanus. The case fatality

from tetanus as reported from a few states of India in the decade

1951-60 suggested that the case-fatality rate was more than 90% in Goa,

Daman and Diu. Between 1956-62, hospital admissions due to tetanus

increased in India, probably due to improvement in the health

consciousness of the population and in its attitude toward the public

health services [9].

In the 1980s, community-based surveys from India

documented that mortality rates due to neonatal tetanus ranged from less

than 5 to more than 60 per 1000 live births. Tetanus alone was causing

23-72% of all neonatal deaths [11]. There were wide variations in the

different states as well as rural and urban areas of India. Data for

mortality due to neonatal tetanus during 1978-83 shows 5-67 and 0-15

neonatal tetanus deaths per 1000 live births in rural and urban India,

respectively. Highest fatality (67/1000 live births) was in rural Uttar

Pradesh.

Current Scenario

World

Around 49 000 newborns died of neonatal tetanus in

2013 (1% of all neonatal deaths) as compared to around 200 000 deaths

(7% of newborn deaths) in the year 2000. Number of countries that have

not eliminated maternal and neonatal tetanus has come down from 59 in

2000 to 19 in 2016 (Table I). Augmentation of

supplementary immunization activities under MNTE initiative has led to

vaccination of more than 170 million women of reproductive age [4,12].

Deliveries conducted by skilled health personnel have also increased

from 59% in 1990 to 71% in 2014.

TABLE I Countries Which Have Not Eliminated Maternal Neonatal Tetanus by 2016.

|

Country |

Maternal Mortality Ratio*

|

|

1 |

Afghanistan |

396 |

|

2 |

Angola |

477 |

|

3 |

Central African republic |

882 |

|

4 |

Chad |

856 |

|

5 |

Congo (DRC) |

442 |

|

6 |

Equatorial Guinea |

342 |

|

7 |

Ethiopia |

356 |

|

8 |

Guinea |

679 |

|

9 |

Haiti |

359 |

|

10 |

Kenya |

510 |

|

11 |

Mali |

587 |

|

12 |

Nigeria |

814 |

|

13 |

Pakistan |

178 |

|

14 |

Papua New Guinea |

215 |

|

15 |

Philippines |

114 |

|

16 |

Somalia |

732 |

|

17 |

Sudan |

311 |

|

18 |

South Sudan |

789 |

|

19 |

Yemen |

385 |

*UNICEF. Trends in Maternal Mortality 1990 to 2015. Estimates by

WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United

Nations Population Division. (http://data.unicef.org/corecode/uploads/document6/uploaded_pdfs/corecode/MMR_executive_summary_

final_mid-res_243.pdf.)

Data Source: Sample Registration System, Government of India and

WHO 2015 global summary of vaccine preventable diseases. |

India

In 1988, 11 849 cases of neonatal tetanus were

reported from India while only 492 were reported in 2014 (95.8%

reduction) [13]. India was declared free of maternal and neonatal

tetanus on 15th May, 2015. Andhra Pradesh was the first, and Nagaland

the last Indian state to achieve the elimination goal [3]. Various

factors contributed to its early elimination from Andhra Pradesh, much

before the rest of India [14]. Tetanus toxoid immunization to all

pregnant women was started in 1979 in the State, as compared to 1983 in

rest of the country. Cash incentives were given to cover the costs

associated with institutional deliveries, and there was a high political

commitment for the cause, leading to increased recruitment of auxiliary

nurse midwife (ANMs). Also, there was an increase in village-level

promotional material on vaccination, and 24-hour service provided in

most peripheral health centers (PHCs).

Strategies Which Helped India Achieve Neonatal

Tetanus Elimination

There has been an overall 44% reduction in neonatal

deaths in India between 1990 (13,54,000) to 2012 (7,58,000). But this

reduction has not been uniform across India. While some states have a

single-digit neonatal mortality rate (NMR), others have an NMR more than

30 [15]. India, in particular, faced unique challenges because of its

economic, cultural, and demographic diversities.

A Cochrane systematic review suggests that a two or

three dose course of tetanus toxoid to pregnant mothers provides

protection against neonatal deaths [16]. Tetanus vaccination of pregnant

women was included in India’s National Immunization Policy in the year

1983. According to NFHS-3 data (2005-06), around 82% of pregnant women

registered for antenatal care were receiving second dose of tetanus

toxoid or booster [17].

Neonatal tetanus had decreased significantly in

developed countries even before tetanus toxoid vaccine was being given

during pregnancy [10]. The main factors responsible were safe delivery

practices and cord care. Moreover the TT2 coverage had remained steady

in India, and had rather decreased in 2013 [14]. It indicates that other

factors have also played an important part in elimination of maternal

and neonatal tetanus from India. Many program have been introduced in

India in the last 25 years to address maternal and newborn health (Table

II) [15].

Table II Maternal and Child Health Programs in India

|

Year of launch |

Health program |

|

1992 |

Child Survival and Safe Motherhood (CSSM) |

|

1997 |

Reproductive Child Health-I (RCH-I) |

|

2005 |

Reproductive Child Health-II (RCH-II)

|

|

2005 |

National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) |

|

2013 |

Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health

(RMNCH+A)

|

|

2013 |

National Health Mission (NHM) |

|

2014 |

India Newborn Action Plan (INAP) |

Though the dose and schedule for tetanus vaccination

has remained same in each of these programs, it is probably the focus on

integrating the reproductive health services and a goal-directed

approach that has helped India to eliminate MNT. Under the’Child

Survival and Safe Motherhood Program’, emphasis was laid on training of

traditional birth attendants and strengthening of first referral units

so that they deal better with high-risk obstetric emergencies [18]. The

‘Reproductive and Child Health’ programs stressed on 24 hour delivery

services at PHCs and referral facilities, and training of MBBS doctors

in emergency obstetric management, to improve skilled birth attendance.

Policy decisions were made to permit health workers to use drugs in

emergency situations to reduce maternal mortality [19]. Government of

India launched Janani Suraksha Yojna (JSY) in 1995 offering conditional

cash transfers. This led to a quantum increase in institutional

deliveries from 26% (NFHS-1, 1992-93) to 72.9% (Coverage Evaluation

Survey, 2009). National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) introduced several

other interventions for maternal and neonatal health in 2005 [3]:

• Village health and nutrition days were started

to increase coverage of TT-containing vaccines in children and

pregnant females;

• All skilled birth attendants were trained for

3-weeks;

• Peripheral health centers were enabled to

provide round the clock maternal and neonatal care services;

• Facility-based neonatal care (FBNC) was

strengthened. Newborn care corners were set up in maternity

facilities; Special neonatal care units were started in district

hospitals; and Newborn stabilization units were established at first

referral units;

• More than 8.9 million accredited social health

activists (ASHAs) were employed to augment the use of health

facilities;

• Skilled birth attendants were given free

disposable delivery kits for distribution to pregnant women; and

• Institutional deliveries were promoted, more so

in pregnant females of lower socio-economic status.

This program was supplemented by Janani Shishu

Suraksha Karyakram (JSSK) in 2011. Under this program, free maternity

services and newborn care were provided by all government health care

institutions. Both the mother and her newborn are entitled to get free

diagnostic services, free drugs including blood transfusion, free diet,

and free referral transport with drop back facility [20]. An

observational study published in 2012 [21] showed that institutional

deliveries increased by 42.6% after implementation of the JSY scheme,

including those among lower socioeconomic strata. With increase in safe

delivery practices, maternal mortality as well as incidence of neonatal

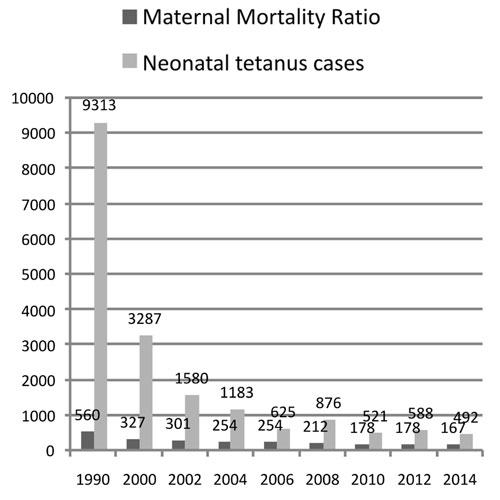

tetanus cases have declined (Fig. 1). Intensive

communication program promoting 5 cleans (clean hands, delivery

surfaces, instruments for cutting the umbilical cord, cord tie and

caring of the umbilical cord) have also contributed to the increase in

safe deliveries [3]. Incentives for ASHAs were also increased in 2012.

|

|

Fig. 1 Neonatal tetanus cases and

maternal mortality ratio, India (1990-2014).

|

Another strategy used for neonatal tetanus

elimination was the use of a high-risk approach in certain

high-incidence states of India, like Rajasthan. Under this approach,

supplementary immunization activities were conducted in these states to

vaccinate >80% of all women of childbearing age with three properly

spaced doses of TT vaccine and the promotion of antenatal care with

clean delivery practices [3].

In addition to this, the Ministry of Health and

Family Welfare (MoHFW) has been intensifying the routine immunization by

conducting campaigns like special immunization weeks and Mission

Indradhanush.

Sustaining Maternal And Neonatal Tetanus Elimination

Unlike measles and polio which are amenable to

eradication, it is impossible to eradicate tetanus as the tetanus spores

cannot be completely removed from the environment [12]. Therefore, we

need to make sustained efforts to maintain the tetanus elimination

status.

Strategies which need strengthening are discussed

below [22]:

Routine immunization (RI) coverage: The routine

immunization in India is a part of the NRHM and is administered by the

MoHFW. The vaccination coverage statistics of India are far from

satisfactory. According to the WHO, the coverage of DTP3 and TT2 of

India in 2013 was 83% and 61%, respectively [13]. According to Coverage

Evaluation Survey 2009 conducted by UNICEF, the most common reasons for

partial or no immunization were that the people did not realize the need

for vaccination and also did not know about the vaccines [23]. In order

to sustain maternal and neonatal tetanus elimination status in India,

routine immunization coverage will have to be strengthened. This can be

done by augmenting IEC activities, ensuring adequate cold chain

facilities, deployment of adequate number of medical and paramedical

personnel for immunization, ensuring vaccine safety, monitoring for

adverse events following immunization (AEFIs), and surveillance of

vaccine preventable diseases (VPDs). There is also a need for adequate

training of health personnel for immunization program.

Poor performing districts should be identified and

corrective strategies should be determined. Mission Indradhanush was

launched in 2014 with a goal to vaccinate all children up to two years

of age and pregnant women with all the available vaccines under

universal immunization program [24]. The MoHFW identified high focus

districts in the country which have the highest number of partially

immunized and unimmunized children. Of these, around 40 per cent

districts are in just four states – Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya

Pradesh, and Odisha. Special immunization drives will be conducted in

these districts to improve routine immunization coverage. More than 20

lakh children were fully vaccinated during phase 1.

Innovation and achieving self-sufficiency in vaccine

production will also go a long way in strengthening RI in India.

Supplementary immunization activities:

Supplementary immunization must complement and not replace routine

immunization. It helps to increase coverage of routine immunization as

well as for catch-up vaccination of unimmunized children. It is one of

the pillars of disease elimination; the other two pillars being routine

immunization and surveillance.

Surveillance: Regular audits of all neonatal

deaths should be done. Continued surveillance of neonatal tetanus cases

is paramount to keep the disease burden in check.

Institutional delivery: More number of ANMs and

ASHAs will have to be trained and regularly incentivized to mobilize

pregnant women to register for antenatal care and safe delivery

practices. Public awareness about government health schemes like JSY and

JSSK and their implementation should be reviewed regularly.

WHO has advised certain strategies to sustain the

MNTE status in India (Box 1) [12]. Unless and until

sustained efforts are made to increase vaccination coverage and safe

deliveries, MNTE status could be difficult to maintain in India.

|

Box 1

WHO Guidelines for Sustaining Maternal and Neonatal Tetanus

Elimination Status [12] |

|

1. To discuss and review annually the

elimination status with main stakeholders including State

immunization officers, data managers, partners, and others as

identified by MoHFW.

2. Maintain the high TT coverage and further

augment it in areas with poor coverage.

3. Increase the rates of booster dose

coverage of children as per national immunization schedule to

ensure life-long protection.

4. Deliveries by skilled birth attendants

should be increased further and neonatal illnesses should be

managed in an integrated program under National Rural Health

Mission.

5. Surveillance.

|

1. Keja K, Chan C, Hayden G, Henderson RH. Expanded

programme on immunization. World Health Stat Q. 1988;41:59-63.

2. Roper MH, Vandelaer JH, Gasse FL. Maternal and

neonatal tetanus. Lancet. 2007;370:1947-59.

3. Maternal and neonatal Tetanus Elimination:

Validation survey in 4 States in India, April 2013. Wkly Epidemiol Rec.

2014;89:177-88.

4. World Health Organization. Maternal and Neonatal

Tetanus (MNT) Elimination. Available from:

http://www.who.int/immunization/diseases/MNTE_initiative/en/index4.html.

Accessed July 25, 2016.

5. India is declared free of maternal and neonatal

tetanus. BMJ. 2015;350:h3092.

6. Schlesinger BE. Proceedings of a Symposium on

Immuni-zation in Childhood. London: Livingstone; 1960. P.73.

7. Matveev KI, Sergeeva TI. Peace-time epidemiology

of tetanus in the USSR and in foreign countries. Zh Mikrobiol Epidemiol

Immunobiol. 1959;30:134-42.

8. Maternal and Neonatal Tetanus Elimination

Initiative. Pampers UNICEF 2010 campaign launch. Available from:

http://www.unicef.org/corporate_partners/files/APPR

OVED_MNT_Report_05.06.10.pdf. Accessed April 25, 2016.

9. Bytchenko B. Geographical distribution of tetanus

in the world, 1951-60. A review of the problem. Bull World Health Organ.

1966;34:71-104.

10. Stanfield JP, Galazka A. Neonatal tetanus in the

world today. Bull World Health Organ. 1984;62:647-69.

11. Basu RN, Sokhey J. A baseline study on neonatal

tetanus in India. Pak Pediatr J. 1982;6:184-97.

12. Maternal and Neonatal Tetanus Elimination:

Validation survey in 4 States and 2 union territories in India, May

2015. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2015;90:589-608.

13. WHO vaccine-preventable diseases: monitoring

system. 2015 global summary. Available from: http://apps.who.int/immunization_monitoring/globalsummary/countries?

countrycriteria%5Bcountry%5D%5B%5D=IND&commit =OK. Accessed May 02,

2016.

14. Bairwa M, Sk S, Rajput M, Khanna P, Malik JS,

Nagar M. India is on the way forward to maternal and neonatal tetanus

elimination! Hum Vaccines Immunotherap. 2012;8:1129-31.

15. Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. Government

of India. INAP: India Newborn Action Plan. September 2014. Available

from: http://www.newbornwhocc.org/INAP_ Final.pdf. Accessed May

02, 2016.

16. Demicheli V, Barale A, Rivetti A. Vaccines for

women for preventing neonatal tetanus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

2015;7:CD002959.

17. National Family Health Survey-3, India. Available

from: http://rchiips.org/nfhs/pdf/India.pdf. Accessed May 04,

2016.

18. Singh M, Paul VK. Maternal and child health

services in India with special focus on perinatal services. J Perinatol.

1997;17:65-9.

19. Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. Child Health

Programme in India. Available from: http://mohfw.nic.in/WriteReadData/l892s/6342515027file14.pdf.

Accessed May 04, 2016.

20. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW).

Government of India. State of India’s Newborns 2014. Available from:

http://www.newbornwhocc.org/SOIN_ PRINTED%2014-9-2014.pdf. Accessed

May 04, 2016.

21. Gupta SK, Pal DK, Tiwari R, Garg R, Shrivastava

AK, Sarawagi R, et al. Impact of Janani Suraksha Yojana on

institutional delivery rate and maternal morbidity and mortality: an

observational study in India. J Health Popul Nutr. 2012;30:464-71.

22. World Health Organization. Achieving and

Sustaining Maternal and Neonatal Tetanus Elimination. Strategic Plan

2012–2015. Available from: http://apps.who.int/immuni

zation_monitoring/MNTEStrategicPlan_E.pdf. Accessed May 04, 2016.

23. Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. Government

of India. Coverage Evaluation Survey 2009. Available from:

https://nrhm-mis.nic.in/SitePages/Pub_Coverage Evaluation.aspx#.

Accessed May 04, 2016.