|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2012;49: 979-982

|

|

Effect of Infliximab ‘Top-down’ Therapy on

Weight Gain in Pediatric Crohn’s Disease

|

|

Mi Jin Kim,

*Woo Yong Lee,

Kyong Eun Choi AND Yon Ho Choe

From the Department of Pediatrics, and *Department of

Surgery, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Samsung Medical

Center, , Seoul, Korea.

Correspondence to: Dr Yon Ho Choe, Department of

Pediatrics, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of

Medicine, 50 Irwon-dong, Gangnam-gu, Seoul 135-710, Korea.

Email: [email protected]

Received: November 04, 2011;

Initial review: January 10, 2012;

Accepted: April 23, 2012.

Published online: June 10, 2012.

PII: S097475591100913-2

|

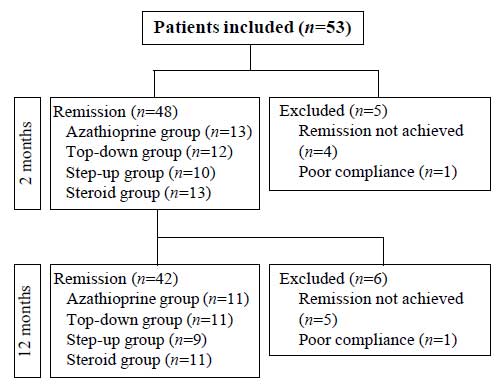

This retrospective-medical-record review was conducted to evaluate

effect of infliximab therapy, particularly with a ‘top-down’ strategy,

on the nutritional parameters of children with Crohn’s disease (CD). 42

patients who were diagnosed with Crohn’s disease at the Pediatric

Gastroenterology center of a tertiary care teaching hospital and

achieved remission at two months and one year after beginning of

treatment were divided into four subgroups according to the treatment

regimen; ‘azathioprine’ group (n = 11), ‘steroid’ group (n

= 11), infliximab ‘top-down’ group (n = 11) and ‘step-up’ group (n

= 9). Weight, height, and serum albumin were measured at diagnosis, and

then at two months and one year after the initiation of treatment. At 2

months, the Z–score increment for weight was highest in the

‘steroid’ group, followed by the ‘top-down’, ‘step-up’, and ‘azathioprine’

groups. At one year, the Z–score increment was highest in

‘top-down’ group, followed by ‘steroid’, ‘azathioprine’, and ‘step-up’

group. There were no significant differences between the four groups in

Z–score increment for height and serum albumin during the study

period. The ‘top-down’ infliximab treatment resulted in superior outcome

for weight gain, compared to the ‘step-up’ therapy and other treatment

regimens.

Key words: Children, Crohn’s disease, Infliximab, Top-down

strategy, Weight gain.

|

|

Crohn’s disease (CD) is characterized by

chronic inflammation involving any portion of the

gastrointestinal tract, and the inflammation contributes to

growth retardation affecting both height and weight [1]. Current

practice guidelines recommend that most patients with active

disease should initially be treated with corticosteroids [2-4].

Although this approach is usually effective for symptom control,

many patients become either resistant or dependent on these

drugs [5] or suffer short-and long-term adverse effects. Over

the last decade, infliximab, a monoclonal immunoglobulin G1

chimeric antibody directed against tumor necrosis factor-a,

has become another therapeutic option for the induction and

maintenance of remission in children with severe CD. The

efficacy of infliximab suggests that, rather than a progressive

course of treatment, early intense (‘top-down’ strategy)

induction may reduce complications associated with conventional

treatment and improve quality of life.

The purpose of this study was to perform a

comparative evaluation of the effects of infliximab therapy with

other treatment modalities, on nutritional parameters for

pediatric patients with CD.

Methods

Among pediatric patients who were diagnosed

with CD in accordance with the European Society for Pediatric

Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition - Porto criteria [6]

at the Samsung Medical Center between March 2001 and March 2010,

we enrolled 42 age-matched patients who achieved remission at

two months and one year after initiation of treatment (Fig.

1). We had a protocol for nutritional evaluation including

height, body weight and serum albumin level and applied it in

all CD patients. A retrospective chart analysis was conducted by

physician notes, laboratory studies, radiology reports,

endoscopy records, and histology reports. Patients with severe

malnutrition affecting growth and development who required

parenteral or enteral nutrition were excluded. This study was

approved by our institutional review board.

|

|

Fig.1 Diagrammatic flow of the

study.

|

The patients (n=42) were divided into

four subgroups according to the treatment regimen. Eleven

patients (‘azathioprine’ group) were treated with azathioprine

and 11 patients (‘steroid’ group) were treated with oral

prednisolone for induction and 11 patients (‘top-down’ group)

were given infliximab from the beginning of treatment. Nine

patients (‘step-up’ group) who had been refractory to

conventional therapy were treated with infliximab (Table

I). Simultaneously all patients were receiving mesalamine (Pentasa,

50-80 mg/kg per day).

TABLE I Baseline Parameters of the Study Population

|

Aza (n=11) |

TD (n=11) |

SU (n=9) |

Steroid (n=11) |

|

Gender, male/female |

8/3 |

8/3 |

6/3 |

8/3 |

|

Age (y)

|

15 (11-18) |

14 (12-18)

|

14 (10-16) |

14 (11-16) |

|

PCDAI score at diagnosis*

|

15.0 (5.0-37.5) |

37.5 (17.5-55.0) |

40.0 (17.5-47.5) |

27.5 (12.5-42.5) |

|

at 2 mo

|

5.0 (0.0-10.0) |

2.5 (0.0-12.5) |

5.0 (0.0-15.0) |

2.5 (0.0-10.0) |

|

at 1 y after beginning treatment |

5.0 (0.0-20.0) |

0.0 (0.0-10.0) |

5.0 (0.0-15.0) |

0.0(0.0-20.0) |

|

All values except gender are median

(range); * P=0.001; PCDAI scores after beginning of

treatment; PCDAI, Pediatric Crohn’s Disease Activity

Index; Aza, azathioprine treatment group; TD, infliximab

‘top-down’ treatment group; SU, infliximab ‘step-up’

treatment group; Steroid, steroid treatment group.

|

In the ‘steroid’ and ‘step-up’ group, oral

corticosteroids (prednisolone, 1-2 mg/kg per day) were used for

induction therapy. Azathioprine (Imuran, 2-3 mg/kg per day) was

provided for maintenance therapy as the conventional treatment.

In the ‘step-up’ and ‘top-down’ group, infliximab (5 mg/kg) was

administered by intravenous infusion at weeks zero, two and six,

in combination with daily azathioprine, and this course was

repeated every eight weeks for ten months thereafter. The group

treated with ‘top-down’ infliximab had not been treated

previously with other medications such as corticosteroids or

other immunomodulators. All patients were followed for at least

12 months.

PCDAI score is calculated from 11 variables

and total score can range from 0 to 100 with higher score

indicating greater disease activity. PCDAI scores were measured

at diagnosis, and then at two and 12 months after the beginning

of treatment. We defined disease remission as a PCDAI score of

less than 10 points and relapse as a score greater than 10

points [7,8]. Moderate to severe disease was defined as having a

score greater than 30 points. Azathioprine was used for patients

with a mild to moderate PCDAI score, and infliximab was used for

patients with a moderate to severe score.

Weight and height were measured at diagnosis,

and then at two months and one year after the beginning of

treatment, except for the ‘step-up’ group. In the ‘step-up’

group, weight and height were measured at the beginning of

infliximab treatment, and then at two months and one year later.

The Z score (standard deviation

scores) was used to evaluate and compare anthropometric

measurements for CD children of various age and gender. A growth

chart for Korean children was used as a reference for body

composition.

Statistical analyses were performed using

Mann-Whitney U-test for unpaired samples and Wilcoxon

signed-rank test for paired samples. Analyses were performed

using Kruskall-Wallis test with Bonferroni’s correction and

Behrens-Fisher method for nonparametric multiple comparisons

(SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). A value of P < 0.05 was

regarded as statistically significant.

Results

Comparison of baseline parameters in the 4

groups are shown in Table I. At two months

following the start of treatment, in the ‘top-down’ group, the

increment in Z-score for weight was superior to those in

the ‘azathioprine’ and ‘step-up’ group (P=0.010 and P=0.036,

respectively). In the ‘steroid’ group, the increment in Z

score was also superior to those in the ‘azathioprine’ and

‘step-up’ group (P=0.001 and P=0.002,

respectively). At one year, in the ‘top-down’ group, the

increment in Z score for weight was superior to those for

the ‘azathioprine’ and ‘step-up’ groups (P=0.009 and P=0.001,

respectively). In the ‘steroid’ group, the increment in Z

score was superior to those in the ‘step-up’ group (P=

0.003). At one year, there were no significant differences

between the four groups in Z score increment for height

and serum albumin at diagnosis, or at two months or one year

after the beginning of treatment (Table II).

TABLE II Z score Increments and Albumin Levels in The Study Population

|

Median Z score increments (range) |

Median albumin levels (g/dL) (range) |

|

Weight |

Height |

Baseline |

2 months |

1 year |

|

Baseline |

2 months* |

1 year# |

Baseline |

2 months |

1 year |

|

|

|

|

Aza |

-0.57 |

0.15 |

0.43 |

-0.25 |

0.28 |

0.56 |

3.8 |

4.1 |

4.3 |

|

(-1.4-2.1) |

(-0.7-0.7) |

(0.0 – 1.5) |

(-2.0 -1.6) |

(-0.1-0.6) |

(0.0-1.0) |

(1.9 -5.1) |

(3.3-4.6) |

(3.4-4.8) |

|

TD |

-0.72 |

0.42 |

0.97 |

-0.48 |

0.18 |

0.67 |

3.5 |

4.4 |

4.4 |

|

(-2.5-2.0) |

(-0.1-0.6) |

(0.0 – 1.5) |

(-2.0 -1.0) |

(-0.2-0.5) |

(0.0 -1.5) |

(2.6 -4.6) |

(3.0 -4.9) |

(3.9-5.0) |

|

SU |

-0.44 |

0.11 |

0.37 |

-0.08 |

0.21 |

0.44 |

3.6 |

3.9 |

4.0 |

|

(-1.9-2.2) |

(-0.1-0.5) |

(-0.9 – 0.8) |

(-1.5-2.3) |

(0.0 -0.4) |

(-0.5-1.4) |

(2.4-4.5) |

(2.9-4.6) |

(3.5-4.6) |

|

Steroid |

-0.53 |

0.66 |

0.73 |

-0.18 |

0.34 |

0.54 |

3.2 |

4.0 |

4.1 |

|

(-1.6-2.0) |

(0.1-0.9) |

(0.1-.5) |

(-1.8-1.2) |

(0.0 -0.9) |

(0.2-1.6) |

(2.5-4.2) |

(3.7-4.5) |

(3.6 -4.7) |

|

Aza, azathioprine treatment group; TD, infliximab

‘top-down’ treatment group; SU, infliximab ‘step-up’

treatment group; Steroid, steroid treatment group;* |

Discussion

One of the critical aims of management in

pediatric CD is growth. Malnutrition is a major treatable cause

of growth failure in inflammatory bowel disease, with weight

loss being present in up to 80% of patients with CD at

presentation [9]. Thus, it is essential to evaluate the outcomes

of specific therapies in terms of their benefit on growth. To

our knowledge, this is the first study to show differences in

the improvement in body weight according to treatment regimens.

Weight, height, and serum albumin level increased during the

treatment period. There was only a significant difference

between treatment groups for weight at a year after treatment.

For height, the one-year follow-up did not seem to be enough to

evaluate linear growth. Serum albumin was restored to a normal

level at 2 months in all groups who achieved remission.

Growth failure mostly appears to be due to

disease activity, with smaller nutritional and iatrogenic

components [10]. The significant difference in weight gain

between ‘top-down’ and ‘azathioprine’ or ‘step-up’ group is most

likely due to the fact that patients of ‘top-down’ group were

malnourished at baseline because of more severe disease.

Infliximab in ‘top-down’ group led to significant improvement in

disease activity and therefore there was marked increase of

weight in this group.

At 2 months, ‘steroid’ group showed the

highest z-score increment of weight, which is because steroids

generally induce short-term weight gain due to increased

appetite. At one year, the ‘top-down’ group showed the highest

Z score increment. We assume that the ‘step-up’ group

placed last at one year because the ‘azathioprine’ group

initially included patients with relatively mild to moderate

PCDAI score.

The current study was limited in that it was

a single-center retrospective study with a small number of

patients, and the follow-up period was only one year. We tried

to include all patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria;

however, selection bias did not disappear completely.

In summary, we found that ‘top-down’

infliximab treatment resulted in a superior outcome for weight

gain, compared to ‘step-up’ therapy and other treatment

regimens. In clinical practice, growth should be carefully

considered as an important criterion for management of CD

children and an important marker of therapeutic efficiency.

Future studies addressing long-term follow-up are needed to

determine the efficacy of infliximab treatment.

Contributors: MJK and YHC:

conceived and designed the study and revised the manuscript for

important intellectual content; YHC: will act as guarantor of

the study; WYL and KEC: analyzed the data and helped in

manuscript writing. The final manuscript was approved by all

authors.

Funding: Grant of the Korea Healthcare

technology R&D Project, Ministry for Health & Welfare Affairs,

Republic of Korea (A092255), and Samsung Biomedical Research

Institute grant, no. SBRI C-A6-229-3; Competing interests:

None stated.

|

What This Study Adds?

•

‘Top-down’ infliximab treatment resulted in superior

outcome for weight gain, compared to the ‘step-up’

therapy and other treatment regimens.

|

References

1. Simon D. Inflammation and growth. J

Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51 (Suppl 3):S133-4.

2. Van Limbergen J, Russell RK, Drummond HE,

Aldhous MC, Round NK, Nimmo ER, et al. Definition of

phenotypic characteristics of childhood-onset inflammatory bowel

disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1114-22.

3. Malchow H, Ewe K, Brandes JW, Goebell H,

Ehms H, Sommer H, et al. European Cooperative Crohn’s

Disease Study (ECCDS): results of drug treatment.

Gastroenterology. 1984;86:249-66.

4. Summers RW, Switz DM, Sessions JT, Jr.,

Becktel JM, Best WR, Kern F, Jr., et al. National

Cooperative Crohn’s Disease Study: results of drug treatment.

Gastroenterology. 1979;77:847-69.

5. Munkholm P, Langholz E, Davidsen M, Binder

V. Frequency of glucocorticoid resistance and dependency in

Crohn’s disease. Gut. 1994;35:360-2.

6. IBD Working Group of the European Society

for Paediatric Gastroenterology HaN. Inflammatory bowel disease

in children and adolescents: recommendations for diagnosis—the

Porto criteria. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;41:1-7.

7. Hyams J, Markowitz J, Otley A, Rosh J,

Mack D, Bousvaros A, et al. Evaluation of the pediatric

crohn disease activity index: a prospective multicenter

experience. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;41:416-21.

8. Otley A, Loonen H, Parekh N, Corey M,

Sherman PM, Griffiths AM. Assessing activity of pediatric

Crohn’s disease: which index to use? Gastroenterology.

1999;116:527-31.

9. Thayu M, Denson LA, Shults J, Zemel BS,

Burnham JM, Baldassano RN, et al. Determinants of changes

in linear growth and body composition in incident pediatric

Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:430-8.

10. Motil KJ, Grand RJ, Davis-Kraft L, Ferlic

LL, Smith EO. Growth failure in children with inflammatory bowel

disease: a prospective study. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:681-91.

|

|

|

|

|