|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2021;58:726-728 |

|

Clinical Profile of

Adolescent Onset Anorexia Nervosa at a Tertiary Care Center

|

|

Kavitha Esther Prasad, 1

Roshni Julia Rajan,1 Mona M

Basker,1 Priya Mary Mammen2,

YS Reshmi1

From 1Division of Adolescent Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, and

2Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Christian Medical

College and Hospital, Vellore, Tamil Nadu.

Correspondence to: Dr Roshni Julia Rajan, Child Health III Unit,

Christian Medical College and Hospital, Vellore, Tamil Nadu.

Email: [email protected]

Received: March 25, 2020;

Initial review: April 11, 2020;

Accepted: September 22, 2020.

Published online: January 02, 2021;

PII: S097475591600267

|

Objectives: To study the

clinical profile and outcome of adolescent onset anorexia nervosa at a

tertiary care center in Southern India. Method: Review of

hospital records of adolescents diagnosed with anorexia nervosa. Outcome

was assessed for those with a follow-up of atleast one year, by

outpatient visit or by a telephonic interview. Findings: Data of

43 patients (28% males) with mean (SD) age at presentation of 13.4 (1.7)

years were included. The mean (SD) BMI at presentation was 13.8 (3.2)

kg/m2, the lowest being 8.3 kg/m2. 33 (76%) patients were hospitalized

for nutritional rehabilitation. Of the 15 patients followed up 1-5 years

later, one had died and 11 had achieved normal weight for age.

Conclusion: As compared to other studies, this study showed a higher

proportion of boys with anorexia nervosa. Further research is necessary

to understand factors affecting long-term outcome.

Keywords: Eating disorder, Management, Outcome.

|

|

A

norexia nervosa is an

eating disorder

characterized primarily by an altered

perception of body image, resulting in

significant weight loss and is influenced by bio-psychosocial

factors. In India, anorexia nervosa is increasingly recognized

as a cause of morbidity and mortality among adolescents. The

reported lifetime prevalence of anorexia nervosa is 0.5-2%, with

a peak age of onset around 13-18 years [1]. Literature reveals a

changing epidemiology of this disorder, with increasing rates of

eating disorder being diagnosed in younger children and in males

[2-5]. Though the prevalence of eating disorders is higher in

Western countries, there is an increasing trend of case reports

from India [5]. With increasing incidence of anorexia nervosa in

children, pediatricians become the first point of contact for

many cases.

Our study aims to describe the clinical

profile of adolescents admitted with anorexia nervosa in a

tertiary care center in Southern India.

METHODS

This was a hospital record review of

adolescents hospitalized with anorexia nervosa and their follow

up after atleast one year of discharge. We reviewed the data of

adolescents (aged 10 to 18 years) who were admitted either in

the adolescent medicine facility or the child and adolescent

psychiatry unit between May, 2006, and December, 2019, and

details of patients with a diagnosis of eating disorder or

anorexia nervosa were extracted. Adolescents who fulfilled the

DSM-V criteria for anorexia nervosa or other specified eating

and feeding disorders (OSFED) were included in this study. Those

with diagnoses of bulimia nervosa, psychogenic vomiting or

unspecified feeding disorders were excluded.

Data regarding the clinical profile and

hospitalization was collected from the hospital database. Follow

up of these patients was done after atleast one year of hospital

discharge following initial hospitalization, either by an

outpatient visit or a telephonic interview. Information

regarding clinical symptoms, weight gain, and school performance

was collected.

Data entry and analysis was done using

Epidata software.

RESULTS

Over the 13 year 8 month period, 43

adolescents of whom 12 (27.9%) were males, were studied.

Anorexia nervosa restricting type was the diagnosis in 23

(53.4%) adolescents, and 9 (20.9%) had binge-purge type. Other

specified feeding and eating disorders (OSFED) were diagnosed in

11 (25.5%).

The mean (SD) age at presentation was 13.4

(1.7) years and the mean (SD) age at onset was 12.4(1.8) years.

The youngest patient was 10 years old. 21 (48.8%) adolescents

had a BMI below the 3rd centile, with one patient having a BMI

of 8.3 Kg/m 2. Loss

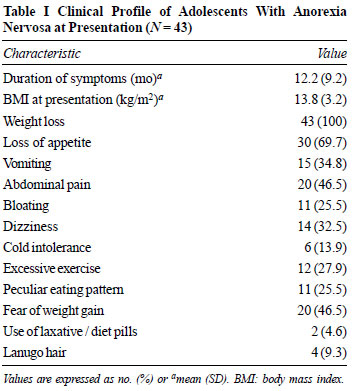

of appetite and abdominal pain were the two most common

presenting symptoms seen in 30 (69.7%) and 20 (46.5%) patients,

respectively (Table I). The mean (SD) calorie intake at

presentation was 388 (247) calories per day. The most common

triggers were peer pressure seen in 15 (34%) patients and family

history of overt eating disorders or a significant adult who was

reportedly health conscious in 8 (18.6%) patients. Men-strual

irregularities were present in 19 (61.2%) adolescent girls, of

whom 5 (26.3%) had primary amenorrhea and 10 (52.6%) had

secondary amenorrhea. Co-morbid conditions such as obsessive

compulsive disorder or depression were present in 11 (25.5%)

patients. There was a family history of psychiatric illness in 9

(20.9%) patients.

|

| |

Microcardia was present in 21 (48.8%)

adolescents. The ECG changes seen in 6 (13.9%) adolescents

included sinus bradycardia, QT prolongation and T wave changes.

Echocardiography was done in five adolescents and was normal.

Seven adolescents had MRI of the brain and abnormal findings

were present in 5 (71.4%) of them. The abnormal findings

included cerebral atrophy, white matter volume loss,

periventricular hyperintensities and pituitary changes. Bone

mineral density was done in 4 patients, 2 (50%) of whom had low

mineral density.

Of the 43 adolescents, 33 (76.7%) were

admitted for nutritional rehabilitation [mean (SD) stay, 13.7

(5.5) days]; the remaining 10 did not require hospitalization

for medical treatment. Of the 33 admitted, 15 required initial

feeding via nasogastric tube, while 1 patient required

nasogastric feeds even at discharge. Hemodynamic instability was

present in 12 (36.3%) of these patients, and refeeding syndrome

was diagnosed in 10 (30.3%) of these patients. At discharge, the

average daily calorie intake was 1935 calories and the average

weekly weight gain was 1.1 kg.

Of the 43 patients, 10 (23.2%) were yet to

complete a 1-year follow-up period, and 18 (41.8%) were lost to

follow-up. One child died 18 months later with severe

hemo-dynamic instability, and complications of electrolyte

imbalance, coagulopathy and shock. Of the remaining 14 (32.5%)

patients, 2 (14.2%) persisted to have symptoms, 1 (7.1%) patient

had become overweight, and the remaining 11 (78.5%) had normal

weight for age.

DISCUSSION

The proportion of males in the study was

higher than that reported in other studies (9-15%) in

adolescents [4,6]. Possible reasons include improved awareness

and diagnoses, and the ease of families to attend an adolescent

medicine clinic, thereby avoiding the stigma of referral to

psychiatry. The age of presentation and onset was similar to

data from Western studies [6,7], while the age of onset was

lower than that reported in Asian studies [8,9]. The average BMI

at presentation was similar to other studies [8,10]. Some

adolescents who were overweight or obese prior to onset of

symptoms, had a significant weight loss over a short period of

time and their BMI at presentation was normal; the adolescents

in this group were either the binge-purge type or the OSFED

category.

Adolescents in the younger age group had a

higher percentage of the binge-purge type of anorexia nervosa,

while those in the older age group were of restrictive type.

This finding is slightly different from previous studies, which

show the younger age group to be more of the restrictive type

[9]. The most common identified trigger factors were peer

pressure and family influence, similar to data from other

studies [9-11].

Mortality rates reported in adolescents

[7,12,13] are lower compared to adults with anorexia [9,14,15].

Our small cohort size precludes comment on mortality, but

further studies are required to better estimate mortality and

outcome. The poor follow-up in our patients reflects the

inability of the family to understand the severity of disease,

stigma of a psychiatric illness and financial burden of

treatment on the family.

Our data will assist pediatricians in

identifying anorexia nervosa early, and lead to appropriate

diagnosis and management to improve overall outcome.

Ethics clearance: Ethics Committee,

Institutional Review Board, CMC, Vellore; No. 11511, dated

September 3, 2018.

Contributors: MMB: concept and the

study design was done; KEP, RJR, RYS, MMB: material preparation,

data collection and analysis were performed; RJR, KEP: written

first draft of the manuscript; MB, PM: revision of the

manuscript; MB: final approval of the manuscript. All authors

have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding: None; Competing interests:

None stated.

|

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS?

• Profile of adolescents with anorexia nervosa at a

tertiary center is described.

|

REFERENCES

1. Weaver L, Liebman R. Assessment of

anorexia nervosa in children and adolescents. Curr

Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13: 93-8.

2. Smink FR, van Hoeken D, Hoek HW.

Epidemiology of eating disorders: Incidence, prevalence and

mortality rates. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14:406-14.

3. Limbers CA, Cohen LA, Gray BA. Eating

disorders in adolescent and young adult males: Prevalence,

diagnosis, and treatment strategies. Adolesc Health Med Ther.

2018; 9:111-16.

4. Pinhas L, Morris A, Crosby RD, Katzman

DK. Incidence and age-specific presentation of restrictive

eating disorders in children: A Canadian paediatric

surveillance program study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.

2011;165:895-99.

5. Basker MM, Mathai S, Korula S, Mammen

PM. Eating disorders among adolescents in a tertiary care

center in India. Indian J Pediatr. 2013;80:211-14.

6. Petkova H, Simic M, Nicholls D, et al.

Incidence of anorexia nervosa in young people in the UK and

Ireland: A national surveillance study. BMJ Open.

2019;9:e027339.

7. Wentz E, Gillberg I, Anckarsäter H,

Gillberg C, Råstam M. Adolescent-onset anorexia nervosa:

18-year outcome. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194:168-74.

8. Kuek A, Utpala R, Lee HY. The clinical

profile of patients with anorexia nervosa in Singapore: A

follow-up descriptive study. Singapore Med J.

2015;56:324-28.

9. Lee HY, Lee EL, Pathy P, Chan YH.

Anorexia nervosa in Singapore: An eight-year retrospective

study. Singapore Med J. 2005;46:275-81.

10. Tanaka H, Kiriike N, Nagata T, Riku

K. Outcome of severe anorexia nervosa patients receiving

inpatient treatment in Japan: An 8-year follow-up study.

Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001;55:389-96.

11. Hilbert A, Pike KM, Goldschmidt AB,

et al. Risk factors across the eating disorders. Psychiatry

Res. 2014;220:500-6.

12. Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Müller B,

Herpertz S, Heussen N, Hebebrand J, Remschmidt H.

Prospective 10-year follow-up in adolescent anorexia nervosa

– course, outcome, psychiatric comorbidity, and psychosocial

adaptation. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2001;42:603-12.

13. Katzman DK. Medical complications in

adolescents with anorexia nervosa: A review of the

literature. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;37:S52-9.

14. Kameoka N, Iga J, Tamaru M, et al.

Risk factors for refeeding hypophosphatemia in Japanese

inpatients with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord.

2016;49:402-06.

15. Fichter MM, Quadflieg N, Hedlund S. Twelve-year course

and outcome predictors of anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord.

2006;39:87-100.

|

|

|

|

|