|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2013;50: 783-785 |

|

Clinico-bacteriological Profile and Outcome of

Empyema

|

|

D Narayanappa, N Rashmi, NA Prasad, and *Anil Kumar

From the Departments of Pediatrics, and * Pediatric

Surgery, JSS Medical College and Hospital, JSS University, Mysore,

Karnataka. India.

Correspondence to: Dr D Narayanappa, No.534, ‘Sinchana’,

15th main, 5th Cross, Saraswathipuram, Mysore 570 009, Karnataka. India.

Email: [email protected]

Received: June 18, 2012;

Initial Review: November 23, 2012;

Accepted: January 28, 2013.

PII: S097475591200518

|

Empyema thoracis is a common

cause of morbidity in children. We conducted a prospective

observational study in 50 children (age 0-15 y) diagnosed with

empyema to study its clinico-bacteriological profile and outcome in

a referral hospital. Staphylococcus aureus was the most

common causative organism, most of them being MRSA, followed by

Pneumococcus and Pseudomonas. Primary video-assisted

thoracoscopy appeared to be a good mode of management with lesser

duration of hospital stay. However, the number of children

undergoing this procedure was very less, to come to any conclusion.

Key words: Empyema thoracis, MRSA,

Video-assisted thocacoscopy.

|

|

It is estimated that 0.6% of childhood pneumonias

progress to empyema, affecting 3.3 per 1,00,000 children [1].

Staphylococcus aureus is the commonest causative organism in

developing countries. There are no universally accepted guidelines for

its management in children. Treatment options include antibiotics alone

or in combination with chest tube drainage, intrapleural fibrinolytics,

VATS (video assisted thoracoscopic surgery), and open decortications

[2,3]. Not many studies are available regarding optimal management of

empyema in children. We conducted this observational study to delineate

the clinico-bacteriological profile of empyema and its outcome with

different modes of management.

Methods

This study was conducted in the Department of

Pediatrics, JSS Medical College Hospital between September 2008 to

September 2010. Fifty children admitted to J.S.S. Hospital, Mysore, with

the diagnosis of empyema in the age group between 0 to 15 years, with

diagnosis of empyema according to ICD-10 code J869 were included [4].

Children with empyema thoracis secondary to trauma/ thoracic

surgery/oesophageal rupture were excluded. Informed parental consent was

taken and relevant data were collected in a preformed proforma.

Institutional ethical clearance was obtained.

All children were subjected to investigations like

complete blood count, ESR, blood culture and sensitivity, Mantoux test,

sputum for acid fast bacilli (if available) and C-reactive protein.

Pleural fluid collected with aseptic precautions by thoracocentesis or

during the time of insertion of intercostal tube for drainage bottle was

analyzed for cell type and count, pH, glucose, LDH levels, Gram’s and

AFB stain and culture and sensitivity for aerobic bacteria. Chest X-ray,

ultrasound scan of chest and CT scan of thorax were done wherever

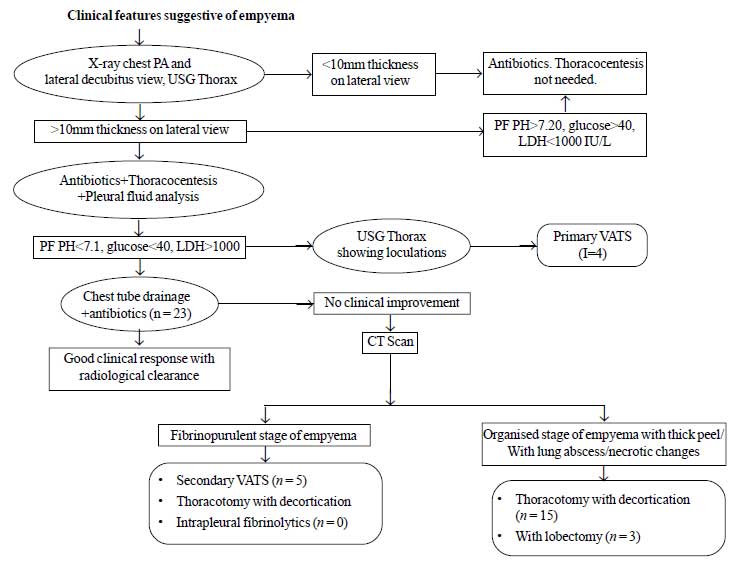

necessary. The mode of management in these cases (indications for) was

decided based on algorithm in Fig. 1 [2]. All the patients

were followed up after 1 month of discharge. Outcome was assessed in

terms of clinical and radiological clearance. Pulmonary function test

(PFT) was performed in children who were above 6 years of age at follow

up. Statistical methods like frequencies, descriptive, crosstabs,

chi-square test and analysis of variance were used to analyze the data,

employing the SPSS 11.0 package.

|

|

Fig. 1 Algorithm for indications for

different modes of management and details of different

management strategies.

|

Results

Out of the 50 cases studied, majority (90%) were in

the age group of 0-5+years (mean age: 3y). Males were more commonly

affected. All children had fever and cough, 35(70%) had hurried

respiration, 4 (8%) had abdominal pain, 4(8%) had chest pain and 2 (4%)

of them had ear discharge. 38(76%) of children had tachypnea, 26(52%)

had tachycardia, 46 (92%) children had dullness on percussion.

Diminished breath sounds were noted in 43(86%) children. Pleural fluid

Gram stain positivity was seen in 17 cases and isolation of organism by

pleural fluid culture was possible in only 20(40%) cases, of which 2

cases had received prior antibiotics. Contingency coefficient of pleural

fluid culture positivity between children who had received prior

antibiotics and those who had not received any, was 0.132, which was

statistically insignificant.

Of 15(30%) cases of pleural fluid culture proven

Staphylococcus aureus isolation, 4 (26.6%) were methicillin

resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). All 15 isolates were

sensitive to linezolid and amikacin, 12 (80%) to clindamycin, 5 isolates

to ceftriaxone and only 3(20%) to penicillin. 12(80%) isolates were

resistant to penicillin, followed by 5(66%) to erythromycin and 3(20%)

to ciprofloxacin. Out of 20 pleural fluid culture proven cases of

empyema, 4(8%) isolates were Pneumococci. All were sensitive to

linezolid and amikacin and 3(75%) isolates were sensitive to penicillin.

One isolate showed growth of Pseudomonas which was sensitive to

ceftazidime, cefotaxim, amikacin, ciprofloxacin and resistant to

tetracyclines.

The management of all the 50 children is shown in Fig

1. The outcome measures included were mean duration of hospital stay and

radiological clearance on follow up. The mean duration of hospital stay

in different modes of management is depicted in Table I.

TABLE I Mean Duration of Hospital Stay (Unit?Hours/days) in Different Modes of Management

|

Numbers n (%)= 50 |

Mean (SD)

|

|

CTD + antibiotics |

23 (46) |

106 (2.92) |

|

PRIM VATS |

4 (8) |

8.5 (1.73) |

|

CTD + antibiotics + Secondary VATS |

5 (10) |

15.0 (4.85) |

|

CTD + antibiotics + Thoracotomy with decortication |

15 (30) |

15.5 (5.01) |

|

CTD + antibiotics + Thoracotomy + Lobectomy |

3 (6) |

26.3 (6.11) |

|

Total |

50 (100) |

13.3 (5.7) |

|

With respect to duration of hospital stay, significant

difference was noted between primary VATS and other modes

(P<0.001). |

Of 23 cases who were treated with CTD and antibiotics

alone, 17 came for follow up after 1 month, 88.2% of them showing good

radiological clearance. 2 (11.8%) children had thickened pleura

radiologically. In children managed with Primary and Secondary VATS,

radiological clearance was 100%. Children undergoing thoracotomy with

decortications showed 93.3% radiological clearance. Children managed by

lobectomy had longer duration of hospital stay of 26.3 days

(statistically significant by Scheffe’s Post Hoc test) and all of them

developed residual scoliosis at follow-up. However there was no

statistically significant difference in radiological clearance between

different treatment strategies. Only five children in the study group

were eligible for pulmonary function test. 1 child was lost to follow

up. PFT done in 4 patients who were more than 6 years were within normal

limits.

One child aged 1 year in the study group expired due

to development of sepsis (Staphylococcus aureus was isolated in

blood culture) with DIC and meningitis.

Discussion

We observed that empyema occurs most commonly in the

under-five age group, and the clinical presentation comprise of,

tachypnea, tachycardia, dull note on percussion and diminished breath

sounds, as also noted in other studies [5-13]. Only 40% of the cases in

our study were confirmed by a positive pleural fluid culture. Girod,

et al. reported states that diagnosis made only by biochemical

criteria may represent an early empyema that may be amenable to a

nonsurgical treatment [14]. However, the yield of pleural fluid culture

also depends on the strength and quality of the culture media. Causative

organisms in our study were also similar to that reported earlier from

other developing countries [5-9]. Most of the isolates of

Staphylococcus (MRSA) were sensitive to linezolid and amikacin.

Other studies however have showed good sensitivity to third generation

cephalosporins, cloxacillin and gentamicin [6,8].

Most of the children in the study were managed by

chest tube drainage, followed by different other modes depending on

their response. Only four children underwent primary VATS, and showed

good outcome in terms of lesser duration of hospital stay and complete

radiological clearance on follow up. However, the number was too low to

come to any conclusion regarding it‘s superiority over other modes.

Studies from India and other countries showed varied outcomes with

respect to radiological clearance, chest deformity and mortality [5-10,

13], which are comparable to those from our study.

Contributors: ND: Guarantor, overall co-ordinator

and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. NR: Conception,

literature search, manuscript writing and critical revision. PNA:

Concept, data acquisition and manuscript writing. AMG: Surgical

management and literature search.

Funding: None; Competing interests: None

stated.

|

What This Study Adds?

• The most common cause of empyema in

children is Staphylococcus aureus, with increasing

prevalence of MRSA.

|

References

1. Kumar V. Epidemiological methods in ARI. Indian J

Pediatr. 1987;54:205-11.

2. Singh M, Singh SK, Choudhary SK. Management of

empyema thoracis in Children. Indian Pediatr. 2002;39:145-57.

3. Balfour-Lynn IM, Abrahamson E, Cohen G, Hartley J,

King S, Parikh D, et al. BTS guidelines for management of pleural

infection in children. Thorax. 2005;60:il-2l.

4. Light RW. Parapneumonic effusions and empyema.

In: Light RW. Pleural Diseases, 3rd edn. Baltimore: Williams

and Wilkins; 1995. p. 129-53.

5. Kumar L, Guptha AP, Mitra S, Yadev K, Pathak IC,

Walia BS, et al. Profile of childhood empyema thoracis in north

India. Indian J Med Res. 1980;72:854-9.

6. Padmini R, Srinivasan S, Puri RK, Nalini P.

Empyema in infancy and childhood. Indian Pediatr 1990;27:447-52.

7. Ghosh S, Chakraborty CK, Chatterjee BD.

Clinicobacteriological study of empyema thoracis in infants and

children. J Indian Med Assoc. 1990;88:189–90.

8. Mishra OP, Das BK, Jain AK, Lahiri TK, Sen PC,

Bhargava V. Clinico-bacteriological study of empyema thoracis in

children. J Trop Pediatr. 1993;39:380-1.

9. Baranwal AK, Singh M, Marwaha RK, Kumar L. Empyema

thoracis: a 10 year comparative review of hospitalized children from

south Asia. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:1009-14.

10. Satpathy SK, Behera CK, Nanda P. Outcome of

parapneumonic empyema. Indian J Pediatr. 2005;72:197-9.

11. Adeyemo AO, Adeyujigbe O, Taiwo OO. Pleural

empyema in infants and children: analysis of 298 cases. J Natl Med

Assoc. 1984;76:799-805.

12. Chonmaitree T, Powell KR. Parapneumonic pleural

effusion and empyema in children: Review of a 19-year experience

1962-1980. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1983;22:414-9.

13. McLaughlin FJ, Goldmann DA, Rosenbaum DM, Harris

GB, Schuster SR, Strieder DJ. Empyema in children: clinical course and

long term follow up. Pediatrics. 1984;73:587-93.

14. Girod CE, Neff TA. How to manage parapneumonic effusion/empyema.

J Respir Dis. 1994; 15:35-44.

|

|

|

|

|