|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2010;47: 309-315 |

|

Single Dose Azithromycin Versus

Ciprofloxacin for Cholera in children: A Randomized

Controlled Trial

|

|

Jaya Shankar Kaushik, Piyush Gupta, MMA Faridi and Shukla Das*

From the Department of Pediatrics and *Department of

Microbiology, University College of Medical Sciences and

Guru Teg Bahadur Hospital, Dilshad Garden, Delhi, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Jaya Shankar Kaushik, 82-B,

Saraswati Kunj, Plot No 25, IP Extension,

Delhi 110 092, India. [email protected]

Received: August 27, 2008;

Initial review: October 13, 2008;

Accepted: March 27, 2009.

Published online:

2009.

May 20. PII:S097475590800521-1

|

|

Abstract

Objective: To compare the clinical and

bacteriological success of single dose treatment with azithromycin and

ciprofloxacin in children with cholera.

Design: Randomized, open labelled, clinical

controlled trial.

Setting: Tertiary care hospital.

Participants: 180 children between 2-12 years,

having watery diarrhea for £24 hr

and severe dehydration, who tested positive for Vibrio cholerae

by hanging drop examination or culture of stool.

Intervention: Azithromycin 20 mg/kg single dose (n=91)

or Ciprofloxacin 20 mg/kg single dose (n=89). Dehydration was

managed according to WHO guidelines.

Main outcome measures: Clinical success

(resolution of diarrhea within 24 hr) and bacteriological success

(cessation of excretion of Vibrio cholerae by day 3). Secondary

outcome variables included duration of diarrhea, duration of excretion

of Vibrio cholerae in stool, fluid requirement, and proportion of

children with clinical or bacteriological relapse.

Results: The rate of clinical success was 94.5%

(86/91) in children treated with Azithromycin and 70.7% (63/89) in those

treated with Ciprofloxacin [RR (95% CI)=1.34 (1.16-1.54); P<0.001].

Bacteriological success was documented in 100% (91/91) children in

Azithromycin group compared to 95.5% (85/89) in Ciprofloxacin group [RR

(95% CI)=1.05 (1.00-1.10); P=0.06]. Patients treated with

Azithromycin had a shorter duration of diarrhea [mean(SD) 54.6 (18.6)

vs 71.5 (29.6) h; mean difference (95% CI) 16.9 (9.6–24.2); P<0.001]

and lesser duration of excretion of Vibrio cholerae [mean(SD)

34.6 (16.3) vs 52.1 (29.2) h; mean difference (95% CI) 17.5 (0.2–24.7),

P<0.001] in children treated with Azithromycin vs Cipro-floxacin.

The amount of intravenous fluid requirement was significantly less among

subjects who received Azithromycin as compared to those who received

Cipro-floxacin [mean(SD) 4704.7(2188.4) vs 3491.1(1520.5) mL; Mean

difference (95% CI) 1213(645.3–1781.9); P<0.001]. Proportion of

children with bacteriological relapse was comparable in two groups [6.7%

(6/89) vs 2.2% (2/91); RR (95% CI) 0.95 (0.89–1.01); P=0.16].

None of the children in either group had a clinical relapse.

Conclusion: Single dose azithromycin is superior

to ciprofloxacin for treating cholera in children.

Key words: Azithromycin, Antibiotic, Cholera, Cipro-floxacin,

Management.

|

|

WHO recommends a 3-5 day course of

furazolidone, trimethoprimsulpha-methoxazole or erythromycin for treatment

of cholera in children; tetracycline may be used for those more than 8

years of age(1-3). However, strains of V. cholerae resistant to

these drugs have been identified in Bangladesh and elsewhere(4).

Ciprofloxacin was found to be effective in treatment of cholera with a

good in vitro activity, long half life, high stool concentration

after ingestion and safety for use in children(5). Single dose

ciprofloxacin has been widely studied in adults(6,7) but studies in

children(8) are limited. Its mechanism of action is different from

penicillin, erythromycin and tetracycline, hence it can be used for

organisms resistant to the traditionally recommended antibiotics. In

recent years, strains of V. cholerae resistant to fluoroquinolones

have also been identified from various parts of India(9-11).

Identification of clinically efficacious alternative antibiotics is

therefore necessary for use in children with cholera.

Azithromycin, a synthetic macrolide antibiotic is an

emerging antibiotic with action against V. cholerae(12). Single

dose treatment with azithromycin has a potential advantage of ease of

administration, good compliance, and reduced cost of treatment. Studies on

treatment of cholera in children with single dose azithromycin are limited

to comparisons with erythromycin(13,14). We compared the efficacy of

single dose of azithromycin to ciprofloxacin for treatment of cholera in

children and hypothesized that azithromycin is at least as effective as

ciprofloxacin in treatment of cholera.

Methods

The study was designed as a randomized, open labelled,

clinical controlled trial; and was conducted in a tertiary care hospital

of India, from March 2006 to February 2007. Clearance was obtained from

the institutional ethical committee. The study protocol was fully

explained to the parents/guardian, and informed written consent was

obtained.

Sample size: The sample size was calculated for

an equivalence study. Clinical success for treatment with single dose

ciprofloxacin was estimated at 94% in a previous study(8). To reach a

predictive power of 80%, with an alpha error of 5% and a beta error of

20%, 87 patients were required in each treatment group to show that the

difference in the rates of clinical success between the treatment groups

did not exceed 10%(15).

Enrolment: Children between 2-12 years, having

watery diarrhea for 24 hr or less, with features of severe dehydration as

per WHO criteria(3), were eligible to be included. Of these, only those

who demonstrated Vibrio cholerae in stool either by a

hanging drop preparation or culture, were finally analyzed. Children with

severe undernutrition (weight for age less than 60% of 50th percentile of

CDC 2000 standards), a coexisting systemic illness, blood in stool; and

those having received an antibiotic/antidiarrheal within preceding 24

hours, were excluded.

Data collection: Baseline data were collected:

this included name, age, address, telephone number, duration of illness,

frequency of diarrhea and vomiting prior to admission, and presence of

associated symptoms including abdominal pain, fever, and abdominal

distension. A history of previous antibiotic/antidiarrheal ingestion in

the last 24 hrs was elicited. Occupation, education and monthly income of

parents were recorded and a socioeconomic status was assigned based on

revised Kuppuswamy classification(16). Evaluation was done for general

hygiene, vitals, and signs of dehydration(2). The present weight was

recorded on a standardized weighing scale to the nearest 0.5 kg. Height

was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm. The same observer obtained all the

measurements.

Randomization and allocation: Eligible children

were allotted a study number. These numbers corresponded to the order of

patients entering the trial. Children were randomized to receive a single

dose of oral azithromycin (20 mg/kg) or ciprofloxacin (20 mg/kg). A simple

randomization was done using a computer generated random number table on a

master list.

Allocation of the treatment group was concealed by

having the names of both the study drug stored in identical sealed

envelope, which were opened after a patient had been enrolled in the study

and assigned a study number. Randomized children were immediately

rehydrated with intravenous Ringer’s lactate solution (30 mL/kg in first ½

hour followed by 70 mL/kg over next 2½ hours). A stool sample was obtained

for hanging drop examination and culture for Vibrio cholerae, as

soon as the child passed stools after admission. The patient was

reassessed for hydration after 3-4 hours and managed further as per the

WHO Guidelines(2).

The assigned Study drug was orally administered after

initial rehydration, under supervision. Eligible subjects received either

a single dose of azithromycin (20 mg/kg) or ciprofloxacin (20 mg/kg). Both

the drugs were available in 100 mg, 250 mg and 500 mg tablets and the dose

was rounded to nearest 50 mg. The dose was repeated if the child vomited

within 10 minutes of drug administration.

Each Study day was defined as 24 hour counted from the

administration of study drug. Children remained in the Study center for 72

hours (day 3) or until resolution of watery diarrhea, whichever was later.

The parents were asked to bring their child back for a follow-up visit on

day 7. If the patient failed to return on the follow-up visit, the parents

were contacted by telephone and asked to come on the next day.

Clinical monitoring was performed on multiple occasions

on the day of admission and subsequently at the end of day 1, 2, 3 and 7.

A record was kept of frequency of stool and vomiting for every 24 hrs. The

amount of intravenous fluid and ORS administered was also recorded at the

end of each Study day. A stool sample or rectal swab was obtained at the

end of day 1, 2, 3 and at follow-up visit (day 7). We also noted for any

possible adverse effects of the drug administered like hypersensitivity

reaction, phototoxicity, tendinopathy and joint pain or swelling.

Microbiological evaluation: The motility of

V. cholerae was seen by hanging drop prepara-tion(17). Stool sample

was transported in alkaline peptone water or Cary Blair media and

processed. The stool samples were cultured in bile salt agar, MacConkey

agar and thiosulphate citrate bile sucrose agar. Plates were incubated at

37ºC for 24 hours. The samples were inoculated in fresh alkaline peptone

water for enrichment and subseqent plating. Bacteriological analysis was

done by standard laboratory techinques(18) and V. cholerae isolates

were serotyped by slide agglutination test using specific antisera (Denca

Saken). Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of the strains was performed

by standard methods.

Outcome measures: The primary outcome variables

were (i) clinical success: defined as resolution of diarrhea

within 72 hours after the start of therapy; and (ii)

bacteriological success: defined as absence of Vibrio cholerae in

the stool sample from day 3 onwards. Resolution of diarrhea was considered

when the child has passed two consecutive formed stools or had not passed

stool for 12 hours.

Secondary outcome variables included (i) total

duration of diarrhea (recovery time) defined as time elapsed from the

entry into study till resolution of diarrhea in hours; (ii) total

requirement of ORS and/or intravenous therapy; (iii) duration of

excretion of V. cholerae in stool; (iv) proportion of

children with clinical relapse (defined when there was cessation of

diarrhea for 1 day or longer followed by return of diarrhea), or

bacteriological relapse (defined as a positive stool culture following a

negative culture report).

Statistical analysis: Data were analysed using

SPSS version 13.0. All quantitative variables (between the groups) were

compared by unpaired t-test; categorical variables were compared by

Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. P<0.05 was considered as

significant. Variables which were measured repeatedly were analysed with

repeated measure ANOVA at 1% level of significance to allow for multiple

comparisons.

Results

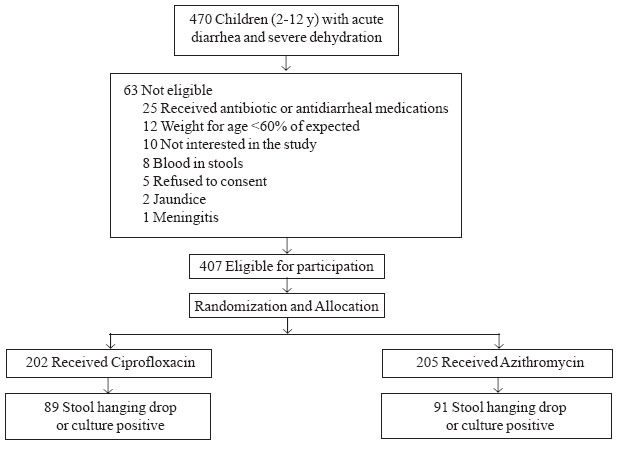

Four hundred seven children were included in the study

and were randomized to receive azithromycin (n=205) or

ciprofloxacin (n=202). Of these, 180 children who tested positive

for V. cholerae by hanging drop examination or culture of the stool

were finally included in the analysis, and designated as "Study subjects".

A total of 89 Study subjects received ciprofloxacin and 91 received

azithromycin (Fig. 1). Baseline characteristics of the study

subjects were comparable between the groups (Table I).

|

|

Fig. 1

Study Flow Chart.

|

TABLE I

Baseline Comparison of Patient Characteristics in the Two Groups

Patient

characteristics |

Ciprofloxacin

(n=89) |

Azithromycin

(n=91) |

P

value |

|

Mean (SD) |

| Age (months) |

64 (33.9) |

70 (37.7) |

0.24 |

| Weight (kg) |

17.4 (7.2) |

18.6 (7.7) |

0.25 |

| Height (cm) |

102.5 (17.8) |

105.3 (18.1) |

0.28 |

| Loose stools* |

15.2 (4.5) |

14.4 (4.7) |

0.24 |

| Duration of diarrhea (h) |

17.9 (7) |

18 (6.8) |

0.94 |

| Frequency of vomiting |

9.7 (6.1) |

9.7 (6.2) |

0.97 |

|

Proportion (%) |

| Male Sexs |

52 (58.4%) |

51 (56.1%) |

0.75 |

| Residence |

| Rural |

3 (3.3%) |

8 (8.8%) |

0.01 |

| Urban |

29 (32.5%) |

13 (14.2%) |

|

| Urban slum |

57 (64%) |

70 (76.9%) |

|

| Socioeconomic status (SES) |

| Lower SES |

19 (21.3%) |

20 (21.9%) |

0.17 |

| Middle SES |

51 (57.3%) |

41 (45.1%) |

|

| Upper SES |

0 (0%) |

1 (1.1%) |

|

| Source of drinking water |

| Treated |

61 (68.5%) |

68 (74.7%) |

0.36 |

| Untreated |

28 (31.5%) |

23 (23.3%) |

|

| Safe water

storage practices |

20 (22.5%) |

22 (24.1%) |

0.78 |

| Open field latrine |

25 (28.1%) |

25 (27.5%) |

0.93 |

| Flush latrine |

64 (71.9%) |

66 (72.5%) |

|

| Proper hand

washing |

53 (59.5%) |

54 (59.3%) |

0.97 |

| Children breastfed |

87 (97.7%) |

88 (96.7%) |

0.67 |

| Frequency of symptoms [n (%)] |

| Vomiting |

78 (87.6%) |

81 (89%) |

0.77 |

| Pain abdomen |

32 (35.9%) |

30 (32.9%) |

0.67 |

| Abdominal distension |

5 (5.6%) |

2 (2.2%) |

0.27 |

| Fever |

4 (4.4%) |

3 (3.2%) |

0.72 |

Means compared with Student’s t-test; proportions compared by Chi-square test/Fisher’s exact test; *Prior to admission.

|

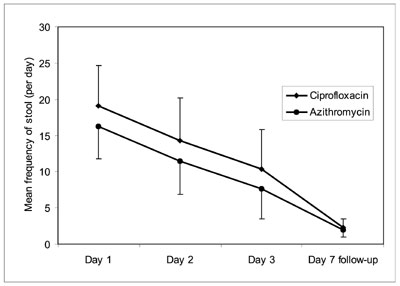

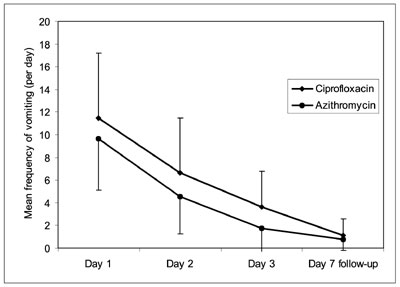

Outcome variables between the two groups are compared

in Table II. Symptomatic improvement was assessed by

comparing the frequency of diarrhea and vomiting. The frequency of stool

and vomiting was significantly lower in children who received azithromycin

as compared to the ciprofloxacin group during the first 72 hours. The rate

of decline in frequency of stool and vomiting was however comparable

between ciprofloxacin and azithromycin groups (Fig. 2a, 2b).

Table II

Comparison of Outcome Variables in Ciprofloxacin and Azithromycin Groups

| Outcome variable |

Ciprofloxacin (n=89) |

Azithromycin (n=91) |

Relative Risk(95% CI) |

P value |

| Number (%) |

| Clinical success |

63 (70.6%) |

86 (94.5%) |

1.33 (0.65–0.86) |

<0.001 |

| Bacteriological success |

85 (95.5%) |

91 (100%) |

1.04 (0.91–0.99) |

0.06 |

| Bacteriological relapse |

6 (6.7%) |

2 (2.2%) |

0.95 (0.89–1.01) |

0.16 |

| Clinical relapse |

Nil |

Nil |

– |

– |

| Mean (SD) |

Mean difference(95% CI) |

| Duration of diarrhea (h) |

71.5 (29.6) |

54.6 (18.6) |

16.9 (9.6–24.2) |

<0.001 |

| Duration of excretion of Vibrio cholerae

(h) |

52.1 (29.2) |

34.6 (16.3) |

17.5 (10.3-24.7) |

<0.001 |

| ORS requirement (mL) |

3473.8 (1341.7) |

3644.4 (1374.9) |

-170.6 (-577.6–236.3) |

0.41 |

| IV fluid requirement (mL) |

4704.7 (2188.4) |

3491.1 (1520.5) |

1213 (645.3–1782.0) |

<0.001 |

|

|

| (a) |

(b) |

|

Fig. 2 Comparison of mean frequency of (a)

diarrheal stools and (b) vomiting between Ciprofloxacin and

Azithromycin groups on day 1, day 2, day 3, and at follow-up visit

(day 7). |

The follow-up loss in first 72 hours of hospital stay

was only 3.3%. However, the follow-up loss beyond day 3 was 18.8%, which

was significant. An intention to treat analysis was used for subjects lost

to follow-up. Baseline patient characteristics were compared for subjects

lost to follow up (n=34) with those who completed the study (n=146)

.

Discussion

Our study concluded that single dose azithromycin is

superior to single dose ciprofloxacin for the treatment of cholera in

children. The rate of clinical success was significantly more in patients

treated with Azithromycin as compared to those treated with Ciprofloxacin,

although the rate of bacteriological success was comparable in the two

groups. Subjects who received Azithromycin had a significantly lesser

duration of diarrhea, shorter duration of excretion of V. cholerae,

and lower requirement of intravenous fluids. Rate of bacteriological

relapse was found to be comparable and none of the subjects in either

group had clinical relapse.

The results pertaining to superiority of single dose

azithromycin over ciprofloxacin are consistent with a previous study(7) in

adults. However, the rates of clinical and bacteriological success with

azithromycin are much higher in our study (95-100%) as compared to earlier

studies with azithromycin(7,13), which reported a success rate of between

70-75%. The discrepancy in the success rates could be attributed to

differing definitions of success adopted in these trials and differences

in baseline characteristics of the enrolled population. We adopted a 72

hours cut off for defining success instead of 48 hours used in the

previous studies(7,8,13). Another possible explanation is that the strains

of Vibrio cholerae in their study setting could have been earlier

exposed to azithromycin. This could lead to emergence of resistance to

azithromycin(19,20). As our study population was not exposed to the drug

for diarrheal illnesses, chances of V. cholerae exposure to the

drug were scanty, which could probably explain such high rates of clinical

and bacteriological success.

Quinolone antimicrobials, especially nalidixic acid,

are widely used in India for treatment of gastrointestinal infections.

Therefore, it could be expected that V. cholerae strains would have

received considerable exposure to these agents and exposure to nalidixic

acid could have been a selective force for quinolone resistance in India.

Hence, ciprofloxacin resistance might have emerged in direct response to

selective pressure exerted by nalidixic acid coupled with disproportionate

use of fluoroquinolones for all bacterial infections in our country. A

consistent increase in median inhibitory concentration (MIC) of V.

cholerae strains to ciprofloxacin has been reported(21,22). The

findings are troublesome as a further increase in MIC may render

ciprofloxacin ineffective in management of cholerae caused by such

multi-drug resistant strains of V. cholerae. Estimation of MIC in

our study could have answered many such queries. Considering the emergence

of fluoroquinolone resistance in our study setting(8), we could possibly

explain that although the sensitivity of ciprofloxacin reaches 99.4% in

our study, the strains probably required higher doses of ciprofloxacin and

for a longer duration to be clinically and bacteriologically effective.

The strength of our study was its robust design. The

sample was statistically sound, practical, suited the convenience and

provided credibility to our results. The only study on efficacy of

azithromycin for treatment of cholera in children has limitation of small

sample size(16), and this study did not analyse the outcome measures in

terms of clinical or bacteriological success. Our study setting was based

on a tertiary care hospital catering to all ailments of an urban

population. This ensures a true picture of diarrheal disease burden as

compared to referral centers catering to only diarrheal disease, as is the

case in most of the previous pediatric studies on cholera. Our study had

certain limitations; the intervention was not masked, there was moderate

follow-up loss and the volume of diarrhea and vomiting was not

ascertained. The population from urban slums is migratory, and it is

typical for them to change homes, which is primarily dictated by job

requirements. We acknowledge this as a reality for such trials conducted

in the developing world, accounting for our follow-up losses. However,

this did not affect the results as shown by comparable baseline

characteristics of study subjects and those lost to follow-up.

We conclude that single dose azithromycin is a useful

alternative for treating cholera in children. Considering the clinical

efficacy and lack of resistance to azithromycin, we advocate that it

should be considered as an option for first line treatment of childhood

cholera in areas where V. cholerae infection are caused by

susceptible strains.

Contributors: The study was conceived by PG. Data

were collected by JSK under the supervision of PG and MMAF; and analyzed

and interpreted by PG, JSK and SD. The article was drafted by JSK and PG.

The final version was approved by all authors.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: Azithromycin was provided by

FDC India limited.

|

What is Already Known?

• Azithromycin is efficacious for treatment of

cholera in adults.

What This Study Adds?

• Azithromycin is superior to ciprofloxacin for treatment of

cholera in children.

|

References

1. Gupta P, Ghai OP. Acute Diarrheal Diseases. In:

Gupta P, Ghai OP, editors. Textbook of Preventive and Social Medicine, 2nd

ed. New Delhi: CBS Publishers and Distributors; 2007. p. 298-305.

2. WHO Guidance on Formulation of National Policy on

the Control of Cholera. From http://www.who.int/topics/cholera/publications/WHO_CDD_

SER_92_16/en. Accessed on January 12, 2007.

3. World Health Organization. Guidelines for Cholera

Control. Geneva: WHO; 1993.

4. Emergence of a unique, multi-drug resistant strain

of Vibrio cholerae O1 in Bangladesh. From: http://www.icddrb.org/images/hsb32_Eng-emergence.pdf.

Accessed on August 20, 2006.

5. Grady R. Safety profile of quinolone antibiotics in

the pediatric population. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2003; 22: 1128-1132.

6. Khan WA, Michael LB, Seas C, Khan EH, Ronan A, Dhar

U, et al. Randomized controlled comparison of single dose

ciprofloxacin and doxycycline for cholera caused by V. cholerae O1

or O139. Lancet 1996; 348: 296-300.

7. Saha D, Karim MM, Khan WA, Ahmed S, Salam MA,

Bennish ML. Single-dose azithromycin for the treatment of cholera in

adults. N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 2452-2462.

8. Saha D, Khan WA, Karim MM, Chowdhury HR, Salam MA,

Bennish ML. Single-dose ciprofloxacin versus 12-dose Erythromycin for

childhood cholera: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet 2005; 366:

1085-1093.

9. Garg P, Chakraborty S, Basu I, Datta S, Rajender K,

Bhattacharya T, et al. Expanding multiple antibiotic resistance

among clinical strains of Vibrio cholerae isolated from 1992-97 in

Calcutta, India. Epidemiol Infect 2000; 124: 393-399.

10. Jesudason MV, Balaji V, Thomson CJ. Quinolone

susceptibility of Vibrio cholerae O1 and O139 isolates from Vellore.

Indian J Med Res 2002; 116: 96-98.

11. Das S, Goyal R, Ramachandran VJ, Gupta S.

Fluoroquinolone resistance in Vibrio cholerae O1: emergence of El

Tor Inaba. Ann Trop Paediatr 2005; 25: 211-212.

12. Jones K, Felmingham J, Ridgway G. In vitro

activity of Azithromycin (CP-62, 993), a novel macrolide, against enteric

pathogens. Drugs Exp Clin Res 1988; 14: 613-615.

13. Khan WA, Saha D, Rahman A, Salam MA, Bogaerts J.

Comparison of single-dose azithromycin and 12-dose 3-day erythromycin for

childhood cholera: A randomized double-blind trial. Lancet 2002; 360:

1722-1727.

14. Bhattacharya MK, Dutta D, Ramamurthy T, Sarkar D,

Singharoy A, Bhattacharya SK. Azithromycin in the treatment of cholera in

children. Acta Paediatr 2003; 92: 676-678.

15. Kim JS. Determining sample size for testing

equivalence. From: http://www.devicelink.com/mddi/archive/97/05/020. html.

Accessed on February 23, 2008.

16. Dasgupta R. Social and Behavioral Sciences in

Health. In: Gupta P, Ghai OP, editors. Textbook of Preventive and Social

Medicine, 2nd ed. New Delhi: CBS Publishers and Distributors; 2007. p.

622-644.

17. Pariija SC. Identification of Vibrio cholerae. In:

Pariija SC (ed). Textbook of Practical Microbiology, 1st ed. New Delhi:

Ahuja Publishing House; 2007. p. 181-183.

18. Chattopadhyay DJ, Sarkar BL, Ansari MQ,

Chakrabarthi BK, Roy MK, Ghosh AN, et al. New phage typing scheme

for Vibrio cholerae O1 biotype ELTOR strains. J Clin Microbiol

1993; 31: 1579-1585.

19. Khan WA, Seas C, Dhar U, Salam MA, Bennish ML.

Treatment of shigellosis: V. Comparison of azithromycin and ciprofloxacin.

A double blind, randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1997; 126:

697-703.

20. Faruque ASG, Alam K, Malek MA, Khan MGY, Ahmed S,

Saha D. Emergence of multi-drug resistant strain of Vibrio cholerae

O1 in Bangladesh and reversal

of their susceptibility to tetracycline after two years. J Health Popul

Nutr 2007; 25: 241-245.

21. Garg P, Sinha S, Chakraborty R, Bhattacharya SK,

Nair GB, Ramamurthy T, et al. Emergence of fluoroquinolone-resistant

strains of Vibrio cholerae O1 biotype ELTOR among hospitalized

patients with cholera in Calcutta, India. Antimicrob Agents Chemother

2001; 45: 1605-1610.

22. Krishna BV, Patil AB, Chandrasekhar MR. Fluoroquinolone-resistant

Vibrio cholerae isolated during a cholera outbreak in India. Trans

R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2006; 100: 224-226.

|

|

|

|

|