|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2021;58:

576-583 |

|

Integrating

Child Protection and Mental Health Concerns in the

Early Childhood Care and Development Program in

India

|

|

Chaitra G Krishna, 1

Sheila Ramaswamy,1

Shekhar Seshadri2

From 1SAMVAD (Support, Advocacy & Mental Health

Interventions for Children in Vulnerable

Circumstances and Distress), Department of Child &

Adolescent Psychiatry; and 2Department of Child and

Adolescent Psychiatry, National Institute of Mental

Health & Neurosciences (NIMHANS); Bangalore,

Karnataka.

Correspondence to: Dr Shekhar Seshadri, Senior

Professor, Department of Child and Adolescent

Psychiatry, and Associate Dean, Behavioral Sciences,

National Institute of Mental Health and

Neurosciences (NIMHANS), Bangalore 560 029,

Karnataka, India.

[email protected]

Published online: February 25, 2021;

PII: S097475591600299

|

|

T he term

‘child protection’ refers to preventing

and responding to violence, exploitation, abuse

and neglect of young children. Article 19 of

the United Nations Convention of Children’s Rights

(UNCRC/CRC), 1989 provides children a specific right

to protection [1]. About 13.5% of India’s

population, 16.45 crore children, are in the age

group 0-6 years [2]. According to a national study

conducted by Ministry of Women and Child Development

(MoWCD), on child abuse in India, 66% are reported

to be physically abused, 50% have faced one or more

forms of sexual abuse and emotional abuse [2,3]. As

per the National Crime Records Bureau’s 2017 report

on crime against children, a total of 129032 cases

were recorded, including kidnapping and abduction,

sexual offences and murder [4]. A total of 32,608

child sexual abuse cases were recorded in 2017

alone, including for children below 5 years of age

[5] and a total of 78,000 orphan and vulnerable

children are residing in child care institutions

under the Integrated Child Protection Scheme (ICPS)

[6]. Child protection is thus becoming an increasing

concern in India, creating new imperatives to

address it amongst all children, but particularly

children below 6 years of age, who due to their age

and developmental abilities are rendered more

vulnerable than older child populations.

Due to paucity of age-specific

data, it is unclear as to what proportion of abused

children are between 0 to 6 years of age. Many

behaviors such as defiance, anxiety to new

situations, which are considered pathological in

older children, constitute normal development in

young children. Thus, it is difficult to

differentiate between normal and pathological

behaviors, making mental health diagnosis in young

children difficult [7]. Due to their developmental

age, and their lower verbal communication skills,

they are also hindered from reporting experiences

[8], consequently rendering them more vulnerable

than older children, to traumatic death and injury

caused due to abuse and neglect [9-11].

There is now considerable

evidence to show that adverse experiences in early

childhood also have a negative impact on young

children’s overall development and so, if not

addressed, may lead to adverse outcomes in later

years. For instance, children’s exposure to frequent

and prolonged abuse, neglect, violence, substance

abuse in caregivers, family and economic stressors,

and poor attachment relations negatively impacts

their mental health, neurodevelopment, psychosocial

development and academic functioning [14-17]. Mental

health is impacted by increasing the risk of

internalizing and externalizing problems such as

anxiety, depression and suicide [18,19], antisocial

behavior and psychopathy [20], substance abuse, and

legal problems in their adult life [21-23]. The

risks of adverse childhood experiences also combine

with the disciplinary strategies used with children,

including all forms of corporal punishment, to

result in increased risk of negative behavioral,

cognitive, psychosocial, and emotio-nal outcomes

among children [24].

Since critical brain development

occurs in the early years of life [25], it is

important to note that child protection in early

childhood critically involves, but is not restricted

to, abuse and neglect. Child protection in early

childhood also entails protection from the adverse

influences of unmet developmental needs along with

the other interventions. According to the Adverse

childhood experiences studies, the relationship

between adverse childhood experiences and negative

health indicators begins early in childhood; child

care service providers thus have an opportunity to

provide interventions that prevent long-term

negative health consequences [26]. Child protection,

therefore involves addressing risks relating to

neglect, (physical, sexual and emotional) abuse, and

absence of opportunities (for learning and

development).

INTEGRATING CHILD PROTECTION INTO EARLY CHILDHOOD

CARE AND DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMS

Early Childhood Care and

Development (ECCD) programs across the world majorly

focus on nutrition and early stimulation along with

other health interventions such as immunization,

hygiene, educational and support measures for

caregivers to ensure consistent care and support for

children. Even though ECCD programs work with

multiple departments, they have limited

colla-boration with child mental health and child

protection systems [27].

While there are child protection

programs around the world, those working

specifically in the context of early childhood, are

relatively limited. For those that do work in the

area of early childhood, there are very few that

integrate ECCD issues with child protection.

Examples of integrated programming include UNICEF’s

programme guidance for early childhood development

[28] and Plan International’s development of program

models and tools to integrate child protection into

ECCD, as reflected in their exploratory studies in

Uganda, Bolivia and Timor-Leste [29]. Save the

Children, has also attempted, in few of their

programs, to integrate child protection into ECCD

but while they focus on orphans and vulnerable

children, they do not have a mental health component

[30].

There are examples of child

violence prevention programs, which have been

successfully implemented both in developed and

developing countries [29,31-35], through parents,

nurses or community health worker in the primary

health care system. These have focused, and

legitimately so, mostly on positive parenting,

monitoring for prevention child maltreatment

(through home visits by community health care

workers), mother–child therapy interventions,

provision of primary health care services and safe

spaces for children to grow and play. However, these

programs have worked largely in family settings–an

approach that India could draw upon but that would

not be entirely applicable to its context, because

the socio-economic situation of many vulnerable

children often does not allow for family members to

be present for the child. Therein lies the

importance, in the Indian context, of the role of

the ECCD workers and the need to integrate child

protection into the government preschool system.

The key objectives of ECCD and

child protection programs are to ensure

age-appropriate development, early stimulation and

primary prevention. The World Health Organization’s

Nurturing care framework also recommends providing

for the children’s physical and emotional needs,

protection from harm along with learning and

development opportunities as its central tenet [36].

Given that ECCD programs qualify as a universal

intervention, their coverage tends to be wide, and

ECCD workers and educators are ideally placed to

implement protection strategies to assist children

at risk of abuse and neglect [37]. Thus, ECCD

programs may serve as effective vehicles to protect

children from adversities.

Furthermore, as erstwhile

described, exacerbated by poverty and other

vulnerabilities, mental health needs of children

from adverse circumstances are high – placing

children at increased risk of continued child

protection problems. Thus, it is imperative for

integrated ECCD and child protection programs to

include child mental health interventions.

Effectively addressing emotional and behavioral

problems that are consequences of protection issues,

would be critical to the successful implementation

of early childhood care and protection services and

programs [9].

We, herein, address the question

of how to integrate child protection and mental

health interventions into existing ECCD programs by

describing the experience of a pilot project in the

Indian context. It provides the rationale,

methodology and content of service delivery for

integrating child protection and mental health

interventions into the existing ECCD program, the

Integrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS),

highlighting emerging concerns and challenges and

drawing from the interventions to show how some of

these were addressed. We also discuss how child care

service providers, particularly pediatricians, can

play a pivotal role in this endeavor.

Experience With a Pilot Project

Prior to this pilot project a

large community-based child and adolescent mental

health service project, had been implemented by us.

The community-based project had executed a resource

mapping and needs assessment for community child and

adolescent mental health services [4], prior to the

start of its activities. With the objective of

promoting early stimulation and optimum development

in children, activities such as implementation of

early stimulation, training and capacity of

Anganwadi workers on early stimulation (child

protection was not a prominent focus of the program

at the time) were conducted. The observations and

experiences of our work are available elsewhere (www.nimhans

childproject.in).

Subsequently this experience was

used to develop a pilot project that focused

exclusively on ECCD inter-ventions, to include child

mental health and protection interventions. In order

to obtain a more specific under-standing of how ICDS

staff view child protection issues, an additional

assessment was done prior to this project, and the

findings incorporated into the design and content of

the interventions.

Context of Intervention

The potential of the integrated

child development scheme: The ICDS

provides a huge opportunity to incorporate

protection components into ECCD because of its

universal coverage agenda, particularly in

socio-economically deprived communities where some

of the most vulnerable children reside. Also, the

anganwadi worker, the key worker in the ICDS scheme,

conducts non-formal education and early stimulation

activities for a given group of children, on a daily

basis, over a relatively long time period (such as a

year). This provides a perfect platform, not only

for early screening and referral for developmental

delays, emotional and beha-vioral and protection

issues, but also to engage children in personal

safety awareness programs.

Protection programs, policies and

laws relevant to young children: As a signatory

to the UNCRC, the Indian Government established a

statutory body, the National Commission for

Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR), in 2007, and

more importantly, the Ministry of Women and Child

Development, launched the Integrated Child

Protection Scheme (ICPS) in 2009. The ICPS

translates into programs, the vision of a secure

environment for all children, as envisaged in the

Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children)

Act, 2015, which in turn is based on principles of

‘protection of child rights’ and ‘best interest of

the child’. It aims at building a protective

environment for children in difficult circumstances,

as well as other vulnerable children, by bringing

together various child protection schemes under one

roof and integrating additional interventions for

protecting children and preventing harm [39].

India has enacted another key law

with regard to child protection – The Protection of

Child Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act 2012 which aims to

effectively address sexual abuse and sexual

exploitation of children. The act defines various

forms of sexual abuse, focuses on mandatory

reporting issues, stringent punishment graded as per

the gravity of the offence, and requisite

child-friendly court processes [40].

Despite the existing range of

ECCD programs and services, there are gaps and

challenges, at knowledge, skill and policy levels,

leading to inadequate realization of child

protection laws and policies. Some of the challenges

observed during the course of our child mental

health and protection work in recent years include:

limited understanding of child protection and

psycho-social issues within child protection system,

lack of focus on protection services for young

children, inadequate knowledge and skills to

identify and address protection concerns, especially

in young children and paucity of systematic and

standardized materials and protocols for child

protection response.

ICDS staff knowledge and skills

in child development and protection issues:

Based on the needs assessment exercise conducted

with anganwadi workers within the ICDS, for a deeper

understanding on the staff’s perspectives on young

child protection, various issues emerged (which also

reflect the general lacunae in the child protection

system in the country). Anganwadi workers have not

been trained in the use of systematic assessments in

child protection, nor in assessment of child mental

health and development issues.

Young children in anganwadis:

The children in the Anganwadis are drawn from

vulnerable homes and communities. Their families

were characterized by low socio-economic status,

residence in urban slums, sub-stance abuse in

caregivers, domestic violence, violence and conflict

(extending through neighbor-hoods). The primary

caregivers were frequently day laborers, so they

were absent for most of the day i.e. as such

children’s interactions with primary caregivers were

limited to a couple of hours a day. Consequently,

they spent the maximum number of hours at the

anganwadi, with the anganwadi worker serving as a

key caregiver.

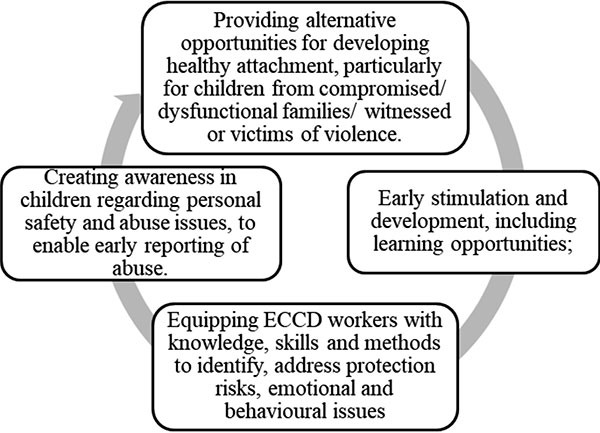

Conceptual framework:

Based on the available literature, a comprehensive

framework for integration would entail the

following: i) early stimulation and

development, including provision for learning

opportunities; ii) providing alternative

opportunities for developing healthy attachment,

particularly for children who are from compromised

or dysfunctional families; iii) creating

awareness in children regarding personal safety and

abuse issues to enable early reporting of abuse

experiences; and iv) equipping ECCD workers

with knowledge, skills and methods to identify

protection risks in young children. Including

emotional and behavioural issues, and to address

them, depending upon the severity.

The aim of the intervention was

to integrate mental health and protection services

for young children between the ages of 0 to 6 years

into the existing the ICDS program.

Methodology

As shown in Fig.1, we used

a multi-pronged approach to provide com-munity-based

mental health and protection services for promotive,

preventive and curative care through direct service

delivery for children, and training and

capacity-building of anganwadi workers.

|

|

Fig. 1 Conceptual

framework for integration of child

protection and mental health with early

childhood care and development.

|

The interventions were

implemented in anganwadis in which the ICDS is

implemented, in vulnerable urban communities the

Bangalore. Anganwadis from the five (urban slums)

near our center were selected. From amongst these,

anganwadis were selected, which had greater

number of children, and more than one center in the

same location were selected – in order to ensure

that a greater number of children would be reached

through a single visit.

Results

In all, during the 7 months, the

interventions were carried out in 31 Anganwadi

centers (Table I). Based on the

context of intervention and the conceptual

framework, two types of interventions were

implemented to integrate child mental health and

protection into the ICDS program, through i) direct

services for children and ii) capacity building

initiatives for ICDS staff.

Table I Interventions and Coverage

| Outcomes |

Coverage |

|

Number of anganwadis and anganwadi workers

reached |

31 |

| Number of individual

assessments done for examining |

237 |

| developmental, mental

health and protection issues |

|

|

Number of group sessions conducted with the

anganwadi

|

190 |

| children |

|

| Number of children

reached through group activities |

276 |

|

One day training workshops for anganwadi

workers |

4 |

|

Number of weekly training sessions for

anganwadi workers |

89 |

Direct services for children:

This was carried out in two distinct steps viz.,

individual assessment of development, mental health

and protection issues in anganwadi children, and

group activities for children in anganwadis.

An assessment proforma comprising

of questions on child development, emotional and

behavioral issues and protection concerns was

developed (available at:

https://www.nimhanschildproject.in/anganwadis-phcs/).

It was based on existing clinical assessment

proformas at the department of child and adolescent

psychiatry in a tertiary care facility. The proforma

has also drawn from the community-based programs

previously executed by the authors, particularly in

young child institutions, where children orphan and

abandoned children, with serious child protection

issues, reside. This assessment was not primarily

aimed at arriving at a diagnosis, but mainly geared

to help child care service providers to identify and

understand children’s problems and vulnerabilities,

with a view to helping them to access appropriate

inter-ventions. Due to the variation in

developmental abilities and needs, the proforma was

adapted to three sub-groups of children under the

age of 6 years: 0 to 1 year, 1 to 3 years and 3 to 6

years.

The assessments were conducted in

the anganwadi. An average of 20 minutes was spent

engaging with the child and about 15 minutes with

the anganwadi worker, for completion of an

individual child’s assessment. To ensure that the

assessments were accurate i.e., that they truly

reflected children’s developmental abilities,

allowing them to respond freely, ice-breakers and

group activities were used to build rapport with

children Developmental checklists were filled out by

observing the child and asking him/her to perform

simple tasks and activities that would allow for

assessment of develop-mental skills and abilities.

Information about the child’s family context and

related protection issues was gathered by

interviewing anganwadi workers and helpers.

Following each assessment, for

mild to moderate developmental, mental health and

protection issues, the anganwadi worker was provided

with first level inputs including what the Anganwadi

worker may do to help the child, and how she could

counsel the parents. For complex issues (such as

developmental disabilities) requiring specialized

assistance, the anganwadi worker was assisted to

refer the child to the dept. of child and adolescent

psychiatry of a tertiary care facility and/or to the

concerned child welfare committee.

Group activities were conducted

with the anganwadi children along with anganwadi

workers (also as part of their capacity building

through demonstration and on-the-job training).

These group sessions with children, focused on

domains of development, mental health and

protection, and comprised of the following:

Activities for promotion of early stimulation and

optimum develop-ment in the five key areas of child

development (physical, social, speech and language,

cognitive and emotional development). including fine

motor activities to develop pre-writing skills;

Activities for socio-emotional develop-ment, with a

focus on helping children recognize and manage

emotions, and develop empathy; and, Activities for

child sexual abuse prevention and personal safety.

Capacity building of anganwadi

workers: This was done using capacity building

workshops and on-the-job training.

One of the key objectives of the

intervention was to build the knowledge and skills

of the anganwadi workers in the areas of child

development, mental health and protection. The

specific training objectives included enabling

anganwadi workers to: Understand the context of

child abuse and neglect, including physical,

emotional and sexual abuse; Identify and provide

first level and emergency responses and necessary

referrals in the context of child abuse and neglect;

Administer the assessment proforma to child

developmental, protection and mental health needs

and issues in individual children; Use personal

safety and sexual abuse prevention module with

preschoolers; and, identify and manage (including

refer) emotional and behavioral problems,

develop-mental and protection issues among young

children.

The training content is detailed

in Box I. It was delivered using creative

participatory and experiential methods, such as role

play, case discussions, simulation games,

demonstrations, brain-storming, pile sorting/

listing – so that the learning was made fun and

interesting, but also to enable workers to learn

necessary methodologies for use with young children.

|

Box I Training Content

for Integrated Child Development, Mental

Health and Protection Programming

Children and childhood

Setting the tone:

Re-connecting with childhood

Child development basics

Power and rights

Child development

Physical development

Speech and language

development

Cognitive development

Social development

Emotional development

(Including demonstration of early

stimulation activities in five domains of

developmentand development of low-cost early

stimulation materials)

Identifying problems and

contexts: the child’s experience and inner

voice

Understanding the child’s

experience and inner voice

Identifying and

understanding child’s behavior using the

context, experience and inner voice

framework

Understanding and

responding to common emotional and behavior

problems in early childhood

Different methods of

responding to emotional and behavioral

concerns

Managing the aggressive

and oppositional child

Management of children

with temper tantrums

Identifying and

understanding an ADHD child

Conceptual understanding

of child protection in early childhood

Introduction to child

protection issues specific to early

childhood

Introducing government

systems and programs available for child

protection

Understanding child

sexual abuse in early childhood

Child sexual abuse basics

First level psychosocial

responses for sexually abused children

Introduction to the child

sexual abuse prevention module

Practicing the child

sexual abuse prevention module

Assessing children for

developmental, mental health and protection

issues in early childhood

Assessment of child

development issues in early childhood

Assessment of emotional

and behavioral problems in early childhood

Assessment of child

protection issues in early childhood

*The content is available as a training

manual at:

https://www.nimhanschildproject.in/training-and-capacity-building/training-manuals-materials-for-child-care-service-providers/

|

Over a 7-month period, training

and capacity building activities were conducted

through 4 one-day workshops, which were held once in

two months, at the tertiary care facility that the

project was based out of. Other times, weekly

sessions were held on an on-going basis, for

clusters of anganwadis (4 to 12 Anganwadi

workers) located near each other. This enabled

Anganwadi workers to avoid travelling long distances

to attend training; and it allowed them to complete

their morning tasks com-fortably in order to free up

their time for the afternoon session. The training

team ensured that a friendly, light-hearted learning

environment was created in the Anganwadi and in

workshops.

Alongside the training, daily

field visits were used by the team, to provide

on-the-job support to the anganwadi workers. This

included demonstrations on conducting activities for

early stimulation and development, and for personal

safety and abuse prevention, administration of the

assessment proforma and management of common

emotional and behavioral problems in young children.

Additionally, revision and recap of some of the

training workshops/sessions were also done in

one-on-one sessions with anganwadi teachers, to help

them link theory and practice issues in the field.

Development of activities and

materials for use with children: In order to

provide Anganwadi workers with standardized methods

in their direct work with children, several

materials have been developed for intervention

purposes. Some of these materials were also

translated into the local language. The materials

include the following: activity book for

socio-emotional develop-ment in pre-school children;

child sexual abuse and personal safety module -

activity-based awareness and learning for

preschoolers and children with developmental

disabilities; early stimulation and development

activity books and flip charts (for use with

parents, teachers and caregivers); Stories for

preschoolers on themes of loss and grief, separation

anxiety and attachment, etc. (material available at:

https://www. nimhanschildproject.

in/interventions/pre-school-0-to-6-years/).

Given the contextual challenges

of the anganwadi workers, the team developed and

adopted several types of strategies, throughout its

implementation processes, so as to provide for a

more enabling learning and work culture and

environment for the workers (Box II).

|

Box II Specific Strategies

Adopted for Capacity Building of Anganwadi

Workers

Use of creative methods

in training, also to understand importance

of child-friendly methods

• Shorter and more

focused learning with an element of

continuity and follow up.

• Contents were tailored

to the learning abilities of the Anganwadi

workers.

• Minimal use of lecture

methods; increased use of experiential,

creative and participatory methods,

• Creation of a sense of

anticipation and enthusiasm amongst the

workers, and also gave them a sense of the

importance of methodology in child work.

Connection, not

correctional approaches

• Listening, recognizing

and validating the Anganwadi workers’

experiences and concerns.

• Assurance that the

intent was to reduce, not increase their

work burden.

• Assurance that the

objectives were neither to criticize nor

report but to understand and support their

work, to enhance what they are already

doing, so as to benefit children.

Helping workers with time

management

• Helping with time

management and enabling balance between

administrative responsibilities and child

work.

• Enabling daily

schedules to allow time for direct work and

non-formal education activities with

children.

Motivational strategies

• Creation of WhatsApp

group as a shared learning platform to allow

for peer learning and appreciation of new

techniques and creativity.

• Encouragement of

posting of videos for visual (peer)

learning.

• Creation of a book of

children’s songs for early stimulation (with

the names of the Anganwadi workers who

contributed).

Revision and review

• Encouragement to

initiate new activities that help translate

theory into concept.

• Competitions wherein

Anganwadi workers were asked to create and

share low cost aids for early stimulation

(with prizes/rewards for some of the most

creative efforts–but in a spirit of fun and

friendship).

• No criticism or blame

was laid on a worker who was unable to do

‘homework’ activities.

• Appreciation for workers who

implemented ‘homework’ activities’, with an

emphasis on the positive aspects of the

activity designed.

|

Process outcomes of interventions:

Since our interventions were not part of a research

study, no measures were used to examine the

effectiveness of the interventions we provided.

However, based on observations and feedback received

from anganwadi workers, some critical qualitative

process outcomes, mainly in terms of anganwadi

workers’ attitudes and learning were found. The

anganwadi workers over come their initial

reluctance, appreciated learning relevant skills and

interventions, and became more aware of the child

protections risks and interventions.

LESSONS LEARNT

As evidenced by the gaps in

literature, there is little data on young child

protection and mental health issues in developing

contexts, including in India. It is critical

therefore for research and intervention studies to

be undertaken in non-clinical, community settings to

better understand health, protection and

developmental issues in some of the most vulnerable

children in our country i.e. those who are least

likely to access protection and mental health

services. Whether for action research or

programmatic interventions, the existing ECCD

program, namely the ICDS, with its coverage and

reach, provides the best chance that a low resource

country such as India has, to protect its most

vulnerable children.

While a great many systemic

measures and changes are required to enable the ICDS

to gear itself to integrated programming that

straddles child development, pro-tection and mental

health, child health experts, who are already

available within the secondary and tertiary levels

of healthcare, can initiate transformations through

the approaches they bring to child services.

Pediatricians usually see children and families

regularly and over a long period, thus having the

advantage of trust and a personal relationship that

allows them to gain a deeper knowledge of the

child’s background, including family systems and

dynamics. The relationship pediatricians have with

the children and parents is devoid of the stigma

usually associated with mental health and child

protection professionals, thus causing parents and

caregivers to be more open and receptive to their

suggestions and inputs [41]. Consequently, they are

well-placed to pick up on child protection concerns

and provide recommendations and/or referrals to

child protection systems [42]. Pediatricians can

also lead the way in child protection in India,

including to provide capacity building support to

the ICDS.

The training courses conducted by

job training centers who provide capacity building

programs to anganwadi workers require major

re-examination and over-hauls, so that they develop

integrated conceptual frameworks and interventions

that cater to the critical domains of early

childhood development, protection and mental health,

and use pedagogies that are appropriate to those who

work with young children–the use of creative and

participatory methodologies in training programs are

more likely to be translated into practice at field

level, in direct work with children.

It is true that anganwadi workers

experience a great many challenges and thus work

under extraordinarily difficult conditions. It is

understandable that high workloads, and lack of

health insurance, to serve as demotivating factors

for them. This is why methodology is as critical as

the content – more so perhaps in this context. The

challenge is not so much about the potential

opportunities these programs and systems provide for

the integration of protection services for young

children, rather how best to plan an intervention

through which the capacities of the service

providers could be developed by navigating through

their many challenges.

We have begun work with state

departments on sharing the models and methods

described in this paper. In conclusion, experiences

from our pilot project suggest that an empathic

approach, that acknowledges the anganwadi workers

challenges and limitations, and takes them into

consideration in program design, would be the way

forward. The use of less conventional approaches

that are built into local traditions and cultures,

creating community-based forums that workers are

keen to be a part of, is a key strategy for making

space and time for their capacity building and for

their work with children. We have begun work with

state departments on sharing the models and methods

described in this paper. In addition to the

commitment of the ICDS scheme and its functionaries,

further work, research and experiences across the

country will determine the scalability of these

methods.

Funding: United Nation

Children’s Fund (UNICEF), India; Competing

interests: None stated.

REFERENCES

1. The United Nations. Convention

on the Rights of the Child. Treaty Series 1989;

1577, 3. Accessed Apr 2, 2020. Available from:

https://www.ohchr.org/documents/professionalinter

est/crc.pdf %0A%0A

2. Statistical Report on Children

of India. Ministry of Women & Child Development.

Governement of India. Children in India 2018 -A

Statistical Appraisal. Accessed Apr 26, 2020.

Available from:

http://mospi.nic.in/sites/default/files/publi

cation_reports/Children%20in%20India%202018%20%E2

%80%93%20A%20Statistical%20 Appraisal_26oct18.pdf

3. Seth R. Protection of children

from abuse and neglect in India. JMAJ. 2013;56;5.

4. National Crime Records Bureau.

Crime in India. Ministry of Home Affairs. Government

of India. Accessed Apr 25, 2020. Available from:

https://ncrb.gov.in/crime-in-india-table-addtional-table-and-chapter-contents?field_date_

value%5 Bvalue%5D%5Byear%5D=2017&field_select_

table_title_ of_ crim_value= 6&items_per_page=All

5. Ministry of Women and Child

Development. PIB: Cases Filed Under POCSO. 2019.

Accessed Apr 25, 2020. Available from:

https://pib.gov.in/newsite/pmreleases.aspx?mincode=

64

6. Ministry of Women and Child

Development G. PIB: Ministry of Women & Child

Development -Year End Review 2018. 2019. Accessed

April 25, 2020. Available from:

https://pib.gov.in/newsite/pmreleases.aspx?mincode=64

7. Koot, H.M., Van Den Oord,

E.J.C.G., Verhulst, F.C. et al. Behavioral and

Emotional Problems in Young Preschoolers:

Cross-Cultural Testing of the Validity of the Child

Behavior Checklist/2-3. J Abnorm Child Psychol.

1997;25:183-96.

8. World Health Organization.

Child abuse and neglect. Accessed April 5, 2020.

Available from: http://www. who.int/violence_injury_prevention

9. Osofsky JD, Lieberman AF. A

call for integrating a mental health perspective

into systems of care for abused and neglected

infants and young children. Am Psychol. 2011;

66:120-8.

10. Margolin G, Gordis EB.

Children’s Exposure to Violence in the Family and

Community. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2004; 13:152-5.

11. Runyan D, May-Chahal C, Ikeda

R, Hassan F, Ramiro L. Child abuse and neglect by

parents and other caregivers. World Rep Violence

Heal. 2002;57-86.

12. Prado EL, Dewey KG. Nutrition

and brain development in early life. Nutr Rev.

2014;72:267-84.

13. Baker-Henningham H, Lopez-Boo

F. Early childhood stimulation interventions in

developing countries: A comprehensive literature

review. IZA Discussion Paper No. 5282. 2010.

Accessed February 25, 2020. Available from:https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_

id= 1700451

14. Saarela JM. Time Does Not

Heal All Wounds: Mortality Following the Death of a

Parent. J Marriage Fam. 2011; 73:236-49.

15. Wade M, Zeanah CH, Fox NA,

Tibu F, Ciolan LE, Nelson CA. Stress sensitization

among severely neglected children and protection by

social enrichment. Nat Commu. 2019; 10:57-71.

16. Mills R, Alati R, O’Callaghan

M, et al. Child abuse and neglect and cognitive

function at 14 years of age: Findings from a birth

cohort. Pediatrics. 2011;127:4-10.

17. Teicher MH, Samson JA,

Anderson CM, Ohashi K. The effects of childhood

maltreatment on brain structure, function and

connectivity. Nature Rev Neurosc. 2016;17: 652-66.

18. Smith M, Mcisaac J-L. Adverse

Childhood Experiences: Early Childhood Educators

Awareness and Perceived Support [Internet]. Mount

Saint Vincent University; 2019. Accessed August 16,

2020. Available from: http://ec.msvu. ca/xmlui/handle/10587/2090

19. Jimenez ME, Wade R Jr, Lin Y,

Morrow LM, Reichman NE. Adverse experiences in early

childhood and kindergarten outcomes. Pediatrics.

2016;137:e20151839.

20. Kolla NJ, Malcolm C, Attard

S, Arenovich T, Blackwood N, Hodgins S. Childhood

maltreatment and aggressive behavior in violent

offenders with psychopathy. Can J Psychiatry.

2013;58:487-94.

21. Putnam FW. The Impact of

Trauma on Child Development. Juv Fam Court J.

2006;57:1-11.

22. Young JC, Widom CS. Long-term

effects of child abuse and neglect on emotion

processing in adulthood. Child Abuse Negl.

2014;38:1369-81.

23. Storr CL, Nicholas Ialongo

SS, Anthony JC, Breslau N. Childhood antecedents of

exposure to traumatic events and posttraumatic

stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164: 119-25.

24. Sege RD, Siegel BS. Effective

discipline to raise healthy children.

Pediatrics.2018;142:e20183112.

25. Tierney AL, Nelson CA. Brain

Development and the Role of Experience in the Early

Years. Zero Three. 2009;30:9-13.

26. Flaherty EG, Thompson R,

Litrownik AJ, et al. Effect of early childhood

adversity on child health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.

2006;160:1232-8.

27. Lannen P, Ziswiler M.

Potential and perils of the early years: The need to

integrate violence prevention and early child

development (ECD+). Aggression Violent Beh. 2014;19:

625-8.

28. United Nation Children’s Fund

(UNICEF). Programme guidance for early childhood

development. 2017 Accessed April 05, 2020. Available

from: https://www.unicef.org/early

childhood/files/FINAL_ECD_Programme_Guidance._

September._2017.pdf

29. Enhancing child protection

through early childhood care and development | Plan

International. Accessed April 12, 2020. Available

from:

https://plan-international.org/publications/enhancing-child-protection-through-early-childhood-care-and-development

30. Save the Children. Early

Childhood Care and Development (ECCD) Various

Modalities of Delivering Early Cognitive Stimulation

Programs for 0-6 year olds. 2016. Accessed March 24,

2020. Available from: https://resourcecentre.save

thechildren.net/node/10016/pdf/alt._eccd_models_

final_0. pdf

31. Prinz RJ, Sanders MR, Shapiro

CJ, Whitaker DJ, Lutzker JR. Population-based

prevention of child maltreatment: The U.S. triple P

system population trial. Prev Sci. 2009;10:1-12.

32. MacMillan HL, Wathen CN,

Barlow J, Fergusson DM, Leventhal JM, Taussig HN.

Interventions to prevent child maltreatment and

associated impairment. Lancet. 2009;373:250-66.

33. Mikton C. Two challenges to

importing evidence-based child maltreatment

prevention programs developed in high-income

countries to low- and middle-income countries:

Generali-zability and affordability. 2012. Accessed

August 15, 2020. Available from:

https://uwe-repository.worktribe.com/output

/954731/two-challengesto-importing-evidence-based-child-maltreatment-prevention-programs-developed-in-high-income-countries-to-low-and-middle-income-countries-generalizability-and-affordability

34. Skeen S, Tomlinson M. A

public health approach to preventing child abuse in

low- and middle-income countries: A call for action.

Int J Psychol. 2013;48:108-16.

35. Puffer ES, Green EP, Chase

RM, et al. Parents make the difference: a

randomized-controlled trial of a parenting

intervention in Liberia. Glob Ment Heal. 2015;2:e15.

36. Jeong J, Franchett E,

Yousafzai AK. World Health Organization

Recommendations on Caregiving Inter-ventions to

Support Early Child Development in the First Three

Years of Life: Report of the Systematic Review of

Evidence. 2018. Accessed August 25, 2020. Available

from: https://www.who. int/maternal_child_adolescent/guidelines/SR_Caregivin_

interventions_ECD_Jeong_Final_05Mar2020_rev.pdf? ua=1

37. Fenton A. Using a Strengths

Approach to Early Childhood Teacher Preparation in

Child Protection using Work-Integrated Education.

Asia-Pacific J Coop Educ. 2013; 14: 3:157-69.

38. Kapil U. Integrated Child

Development Services (ICDS) scheme/ : A program for

holistic development of children in India. Indian J

Pediatr. 2002;69:597-601.

39. Child Related Legislation |

Ministry of Women & Child Development | Government

of India. Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection Of

Children) Act, 2015 [Internet]. Accessed September

14, 2020. Available from:

https://wcd.nic.in/acts/

juvenile-justice-care-and-protection-children-act-2015

40. Protection of The Protection

of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012

[Internet]. Ministry of Women & Child Development,

Government of India. Accessed April 2, 2020.

Available from: https://wcd.nic.in/act/2315

41. Dubowitz H. Pediatrician’s

role in preventing child maltreatment. Pediatr Clin

North Am. 1990;37:989-1002.

42. Keeshin BR, Dubowitz H. Childhood neglect:

The role of the paediatrician. Paediatr Child

Health. 2013;18:e39-43.

|

|

|

|

|