|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2021;58:572-575 |

|

Impact of Comorbidities

on Outcome in Children With COVID-19 at a Tertiary Care

Pediatric Hospital

|

|

Dipti Kapoor, Virendra Kumar, Harish Pemde, Preeti Singh

From Department of Pediatrics, Lady Hardinge Medical College, New

Delhi.

Correspondence to: Dr Dipti Kapoor, Associate Professor,

Department of Pediatrics, Lady Hardinge Medical College,

New Delhi 110 001.

[email protected]

Received: February 09, 2021;

Initial review: March 09, 2021;

Accepted: May 14, 2021.

|

Objective: To study the various comorbidities and

their impact on outcome of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus

2 (SARS-CoV-2) infected children. Methodology: Review of medical

records of 120 children (58.4% males), aged 1 month to 18 years,

admitted between 1 March and 31 December, 2020 with at least one

positive RT-PCR test for SARS-CoV-2. Clinical and demographic variables

were compared between children with and without co-morbidities.

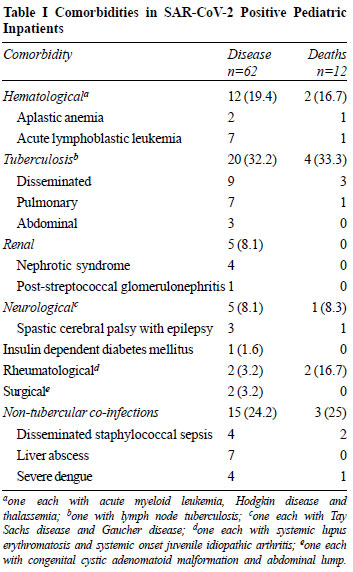

Results: 62 (51.7%) children had comorbidities. The most common

comorbidity was tuberculosis (32.3%) followed by other infections

(27.4%) and hematological (19.4%) conditions. Fever (89.2%) was the most

common clinical feature followed by respiratory (52.5%) and

gastrointestinal (32.5%) manifestations. There was no significant

difference in the severity of COVID illness, length of hospital stay and

adverse outcomes (ventilation and mortality) among children with and

without comorbidities. Conclusion: The presence of a comorbid

illness in pediatric inpatients with COVID-19 did not impact the illness

severity, length of hospitalization, ventilation requirement and

mortality.

Keywords: Mortality, Outcome, Tuberculosis, Ventilation.

|

|

T

he Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome

Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic has

evolved rapidly leading to a multitude of presentations and

variable severity, with substantial information regarding

clinical manifestations and outcomes of coronavirus disease

(COVID-19) in adults. It has been observed that presence of

comorbidities is associated with severe illness and worse

outcomes in adults infected with SARS-CoV-2 [1,2], but our

knowledge about clinical characteristics as well as outcomes of

COVID-19 infected children with comorbidities is limited.

Moreover, there is limited literature on the spectrum of

pediatric comorbidities and their outcome in association with

SARS-CoV-2 infection from our country, which tends to be

entirely different from those observed in the children from

developed countries [3]. This study was planned to examine the

effect of comorbidities with regard to disease presentation,

evolution and outcomes in children infected with SARS-CoV-2.

METHODS

This case record review was undertaken at a

tertiary care pediatric teaching hospital in northern India.

During the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak, any child brought with history

of recent onset fever, cough and/or fast breathing or other

suggestive symptoms like recent onset fever with diarrhea or

contact with COVID-19 positive patient was tested with RT-PCR

test for SARS-CoV-2. These children were also screened for

presence of any comorbidity. Comorbidity was defined as any

distinct additional acute or chronic condition that has existed

or may occur during the clinical course of a patient who has the

index disease under study, and might alter the course of disease

or the outcome [4].

Based on the results of confirmatory RT-PCR

and clinical assessment, cases were classified as asymptomatic,

mild, moderate and severe as per standard guidelines [5]. The

criteria for admission for suspected COVID-19 illness included

any of the following: respiratory distress, SpO2 on room air

<94, shock/poor peripheral perfusion, poor oral intake or

lethargy, specifically in infants and young children and/ or

presence of seizures or encephalopathy [6]. Based on the results

of confirmatory RT-PCR and clinical assessment, hospital

treatment or home isolation measures were instituted with

contact tracing measures as applicable (in accordance with the

local prevailing guidelines). The patients were managed as per

the standard WHO protocol [5].

All children 1 month to 18 years of age, with

at least one positive RT-PCR test for SARS-CoV-2 and requiring

admission between 1 March and 31 December, 2020 were included in

the study. A special COVID ward was created during the ongoing

pandemic for care of these children. Epidemiological,

demographic, clinical, treatment, and outcome data of children

with and without comorbidities was extracted from the case

records and compared. The study was reviewed and approved by the

institutional ethical committee with a waiver of consent for

data collection.

Statistical analysis: Comparison of means

between the two groups i.e., children with and without

comorbidities was performed using the two-sample Student t-test.

Categorical data were compared using Chi-square test. All tests

were 2-tailed with the threshold level of significance at P<0.05.

Statistical analysis was performed using STATA 14.2.

RESULTS

A total of 3180 suspected children were

tested for SARS-CoV-2; 295 (9.27%) children tested positive.

Amongst the latter, 120 SARS-CoV-2 positive children (70 boys)

required admission in the COVID ward. Fever (89.2%) was the most

common clinical feature at the time of presentation, and 64

(53.3%) had severe acute malnutrition or thinness. Comorbidities

were seen in 62 (51.7%) children. The most common comorbidities

were infections like tuberculosis (32.3%) followed by other

infections (27.4%) (Table I).

|

| |

The mortality rate in admitted patients was

24.2% (n=29). There was no difference in the clinical

characteristics of admitted children with and without

comorbidities with respect to baseline characteristics. There

was no statistical difference in the severity of COVID illness,

mean duration of hospital stay and adverse outcomes like

ventilation and mortality among the two groups (Table II).

However, severe anemia and thrombocytopenia were present in

significantly higher number of children with comorbidities (Table

II).

DISCUSSION

The clinical presentation in our cohort is

similar to that observed by previous studies [7]. There was no

significant difference in the clinical symptomatology, severity

of COVID illness, mean duration of hospital stay and adverse

outcomes among the children with and without comorbidities.

Tsankov, et al. [5] in their meta-analysis

observed that the most common comorbidity in children infected

with COVID-19 infection was obesity; whereas, we observed that

more than 50% of our patients were underweight for age. The

other comorbidities observed in their study were chronic

respiratory conditions, cardiovascular disorders and

neuromuscular diseases [5], whereas in our study where other

infections were the most common comorbidities. The mortality

rate observed in our study is higher than that reported globally

[7], presumably due to referral bias due to our center being one

of the largest tertiary care pediatric hospital in the public

sector in this region.

There is a dearth of published literature on

outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infected children with various

comorbidities [8-11]. Three children with disseminated

tuberculosis developed acute respiratory distress syndrome

(ARDS) and multi-organ failure syndrome (MODS), and one died due

to raised intracranial tension with neurogenic shock. The

children with hematological disorders died secondary to febrile

neutropenia with associated septicemia and catecholamine

refractory shock. One child with spastic cerebral palsy was

admitted with severe pneumonia and status epilepticus and went

on to develop ARDS. The patient with systemic lupus

erythematosus developed severe pneumonia with ARDS and acute

kidney injury, whereas the patient with systemic onset juvenile

idiopathic arthritis died due to macrophage activation syndrome

and MODS. Two children died due to disseminated staphylococcal

infection with catechola-mine refractory shock, and one due to

severe dengue with disseminated intravascular coagulation. The

mortality was not significantly different across groups,

possibly because most of our patients with comorbidities were

under regular follow-up in our hospital and were well versed

with the system, they might have presented early or might had

been diagnosed early with symptoms of COVID-19 infection.

Alternatively, some of these children were on immunomodulatory

and immunosuppressant drugs, which could also have modified the

course of infection by interfering with the cytokine storm

responsi-ble for organ damage in COVID-19 [12]. Most of the

SARS-CoV-2 infected children without comorbidities presented in

advanced and decompensated clinical condition, pre-sumably

secondary to suboptimal management caused by delay in diagnosis,

initiation of appropriate treatment, referral or transport

during this unprecedented time of ongoing pandemic. However,

this observation needs to be further evaluated in prospective

studies with larger sample size.

Tsankov, et al. [5] in their meta-analysis

also concluded that they could not determine whether

comorbidities increase risk of severe COVID-19 in children.

However, our observations are in contrast to those observed by

Rao, et al. [13], who observed that presence of comorbidity

increases the severity of COVID-19 disease.

Our study had limitations of having a

retrospective design, small sample size and lack of follow-up.

In spite of these shortcomings, this study provides preliminary

data on the spectrum and outcome of comorbidities in children

infected with SARS-CoV-2.

To conclude, the most common comorbidities

observed in COVID infected children were infections like

tuberculosis and other co-infections. There was no significant

increase in the severity of COVID illness, duration of hospital

stay or adverse outcome in these children. However, this

observation does not understate the vulnerability of these

children to develop severe illness and they should take all

necessary precautions to avoid getting infected with SARS CoV-2.

Further studies examining the effects of specific well-defined

comorbidities are warranted to examine the effects that

pediatric underlying conditions play in COVID-19 severity.

Ethical clearance: Institutional

Ethical Committee, LH Medical College; No. LHMC/IEC/2020/97,

dated November 6, 2020.

Contributors: DK: collected data and

wrote the initial manuscript; VK, PK: critically analyzed the

manuscript; PS: helped in data collection and revision of

manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Funding: None; Competing

interests: None stated.

|

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS?

• Presence of a comorbid illness was

not associated with increase in the severity of COVID

illness, length of hospital stay or adverse outcome in

children.

|

REFERENCES

1. Guan W, Liang W, Zhao Y, et al.

Comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with COVID-19 in

China: A nationwide analysis. European Respiratory J. 2020; 55:

2000547

2. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course

and risk factors for mortality of adult in-patients with

COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A retrospective cohort study. The

Lancet. 2020; 395:1054-62,

3. Tsankov BK, Allaire JM, Irvine MA, et al.

Severe COVID-19 Infection and pediatric comorbidities: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Intern J Infect Dis. 2021;

103: 246-56.

4. Valdres J M, Starfield b, Sibbald B, et

al. Defining comor-bidity: implications for understanding health

and health services. Ann Fam Med. 2009; 7: 357-63.

5. Clinical management of severe acute

respiratory infection when COVID-19 is suspected. Accessed

October 31, 2020. Available at:

https://www.who.int/publications-detail/clinical-management-of-severe-acuterespiratory-infection-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-issuspected

6. Dong Y, Mo X, Hu Y, et al. Epidemiological

characteristics of 2143 pediatric patients with 2019 coronavirus

disease in China. Pediatrics. 2020; e20200702.

7. Meena J, Yadav J, Saini L, et al. Clinical

features and outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children: A

syste-matic review and meta-analysis. Indian Pediatr. 2020; 57:

820-26.

8. Shrinivasan R, Rane S, Pai M. India’s

syndemic of Tuberculosis and COVID-19. BMJ Global Health. 2020;

5: e003979.

9. Girmenia C, Gentile G, Micozzi A, et al.

COVID-19 in patients with hematologic disorders undergoing

therapy: Perspective of a large referral hematology center in

Rome. Acta Haematol. 2020; 143: 574-82.

10. Adeiza SS, Shuaibu AB, Shuaibu GM. Random

effects meta-analysis of COVID-19/S. Aureus partnership in

co-infection GMS. Hygiene and Infection Control. 2020;15:

2196-5226.

11. Saddique A, Rana MS, Alam MM, et al.

Emergence of co-infection of COVID-19 and dengue: A serious

public health threat. J Infect. 2020;81:16-18.

12. Collange O, Tacquard C, Delabranche X, et

al. Coronavirus disease 2019: associated multiple organ

damage. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7:249.

13. Rao S, Gavali V, Prabhu S, et al. Outcome of children

admitted with SARS-CoV-2 infection: Experiences from a pediatric

public hospital. Indian Pediatr. 2021;58:358-62.

|

|

|

|

|