|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2021;58:568-571 |

|

Characteristics and

Transmission Dynamics of COVID-19 in Healthcare Workers in a

Pediatric COVID-Care Hospital in Mumbai

|

|

Ambreen Pandrowala,1

Shaheen Shaikh,2 Mahesh

Balsekar,1 Suverna Kirolkar,2

Soonu Udani3

From Departments of 1Pediatrics, 2Microbiology, and 3Critical Care

and Emergency Services, SRCC Children’s Hospital managed by Narayana

Health, Mumbai, Maharashtra.

Correspondence to: Dr Ambreen Pandrowala, Department of Pediatrics,

SRCC Children’s Hospital, Mahalaxmi,

Mumbai 400 034, India.

Email: [email protected]

Received: December 16, 2020;

Initial review: December 27, 2020;

Accepted: February 06, 2021.

Published online: February 19, 2021;

PII: S097475591600288

|

Objective: To evaluate if Healthcare workers

(HCWs) at the frontline of COVID-19 response in a pediatric hospital are

at an increased risk of acquiring SARS-CoV-2. Methods: The

Hospital Infection Control Committee (HICC) and virology testing records

were combined to identify SARS-CoV-2 positive HCWs and study the

transmission dynamics of COVID-19 over 6 months. Results:

COVID-19 cases in our HCWs cohort rose and declined parallel to

community cases. Forty two out of 534 HCWs (8%) were SARS-CoV-2 positive

with no fatalities. No clinical staff in the special COVID ward or ICU

was positive. Significant proportion of non-clinical staff (30%) were

SARS-CoV-2 positive. About 70% of SARS-CoV-2 positive staff had likely

community acquisition, with a significant proportion having travelled by

public transport or having a contact history with a positive case in the

community. Twenty four percent of positive staff were asymptomatic and

detected positive on re-joining test. Conclusions: Sustained

transmission of SARS-CoV-2 did not occur in our cohort beyond community

transmission. Appropriate PPE use, strict and constantly improving

infection control measures and testing of both clinical and non-clinical

staff were essential methods for restricting transmission amongst HCWs.

Keywords: COVID-19, Healthcare workers, Testing, SARS-CoV-2.

|

|

T

he coronavirus disease

2019 (COVID-19) pandemic started in Wuhan, China in

December, 2019. Nosocomial transmission has been a significant

concern right from the start of the pandemic with one-third of

the initial cohort of COVID-19 patients being healthcare workers

(HCWs) and hospitalized patients [1]. In publications so far,

healthcare workers (HCW) infection rates in China, Italy and USA

have been reported as 3.8%, 10% and 19%, respectively with

fatality up to 1.2% [2].

Union health ministry data shows that the

positivity rate amongst HCWs in Maharashtra was 16%. Mumbai was

one of the first cities significantly affected by the pandemic

in India. Our hospital is a 200-bedded tertiary level pediatric

centre. Healthcare workers showing any symptoms were tested for

SARS-CoV-2 from late March, 2020. All routine work was suspended

and only emergencies were managed from 20 March, 2020, when

Mumbai had recorded 50 cases of COVID-19. Our center was

designated as a pediatric COVID care centre from 6 April, 2020

onwards. The present study was aimed to analyze the

characteristics and transmission dynamics of COVID-19 in HCWs

over first 6 months of the pandemic at a tertiary pediatric

COVID care setup in Mumbai.

METHODS

Any employee who was working in hospital

premises with or without direct patient contact was included as

a HCW. This included individuals employed directly by the

hospital or via a company in contract with the hospital. All

HCWs – both clinical and non-clinical, were tested if any of the

following symptoms were present- fever, cough, sore throat, body

ache, headache, vomiting and diarrhoea; or if re-joining work

after a leave of more than 14 days. Testing was done with a

nasopharyngeal swab for SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR by an ICMR approved

kit having 99% sensitivity and specificity. Healthcare workers

were encouraged to self-test, if required under supervision to

minimize exposure to other HCWs. Self-collection has been found

to be an appropriate and reliable alternative to HCW collection

[3,4]. Awaiting results, HCWs were sent for home isolation or

quarantined in the hospital staff quarters. Healthcare workers

that tested positive were evaluated by a member of the hospital

infection control committee (HICC) for contact tracing. Those at

high risk exposure (exposure >15 min without mask, less than a

meter distance) were quarantined for 14 days with a repeat

SARS-CoV-2 RTPCR done on day 12 or 13 before re-joining work

[5]. All positive HCWs followed Municipal Corporation of Greater

Mumbai (MCGM) guidelines for home or institutional quarantine

and re-joined work after testing negative for SARS-CoV-2. Once

travel restrictions were lifted, details of travel i.e.;

self-driven vs public transport were documented at the time of

contact tracing. The virology laboratory data of HCWs tested and

HICC team data for category of staff and contact tracing from

March, 2020 to August, 2020 was retrospectively analysed after

approval. Exposure was defined as hospital exposure when there

was contact with a SARS-CoV-2 positive patient or staff in

hospital premises and for individuals working in areas of the

hospital like Emergency room, radiology etc. where exposure to

SARS-CoV-2 unknown status is high, and community exposure was

defined as any HCW who was SARS-CoV-2 positive with history of

exposure to SARS-CoV-2 in the community including family members

and during travel. Exposure was consi-dered likely community

acquired if there was no exposure to SARS-CoV-2 positive or

unknown status patient without breach in social distancing

measures with colleagues. Home leave was defined as leave from

work for more than 14 days and new employees. Hostel exposure

included nurses who were residing in the hostel and also staff

who preferred not going home during the pandemic and were

residing in hospital quarters. Individuals exposed to positive

staff residing in the same room/flat were considered as high

risk exposure.

Personal protective equipment (PPE) donning

and doffing training was carried out for HCWs. PPE use was

decided based on location and risk category as per Ministry of

Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW) guidelines [6]. As the

pandemic progressed and we learnt more about the transmission

dynamics, changes were made to infection control protocols and

staff were briefed about it.

RESULTS

Five hundred and thirty four HCWs were tested

during 6 months with 42 HCWs (8%) positive for SARS-CoV-2

without any fatalities. The monthly incidence of SARS-CoV-2

positivity in HCWs is depicted in Fig. 1. Peak incidence

of cases in Mumbai was seen in June [7]. Cases in HCWs rose and

fell parallel to community incidence.

|

|

Fig. 1 Healthcare workers tested

Monthly for SARS-CoV-2 in the first six months of

the pandemic.

|

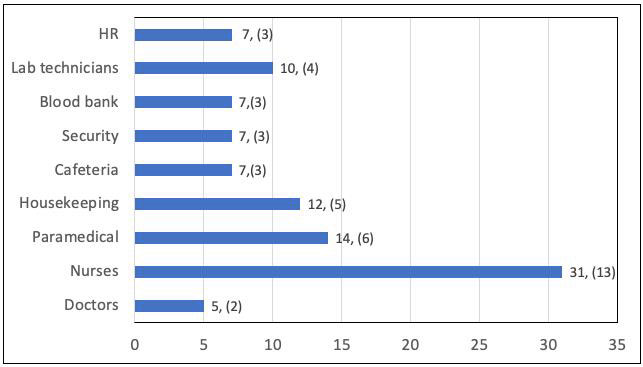

Nurses had the highest incidence of

SARS-CoV-2 positivity; 13 out of 42 (31%) although only 3 out of

13 (23%) had direct high risk patient exposure in the emergency

room and day care unit (Fig. 2). Fourteen percent (6 out

of 42) positive cases were seen in cafeteria and human resource

personnel. Clustering of cases was seen in blood bank and

amongst laboratory technicians. Doctors were least positive in

our cohort (2 out of 42).

Number of staff positive in brackets. HR-Human resources

personnel

|

|

Fig. 2 Percentage

positivity in the category of staff tested.

|

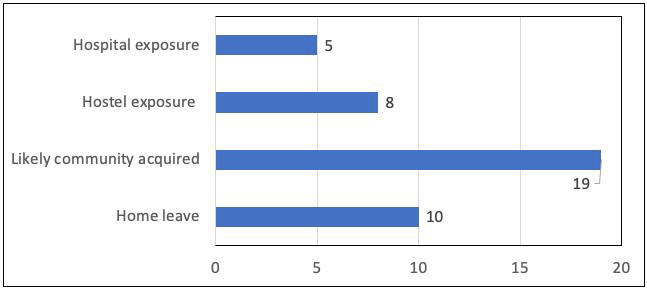

Almost 70% (29 out of 42) of the positive

cases had no high risk exposure in the hospital and were

classified as likely community acquired (Fig. 3). Amongst

high risk exposure areas- day care area, suspected and positive

COVID ward, and COVID ICU had the least SARS-CoV-2 positivity.

No doctor or nursing staff working in COVID wards or ICU tested

positive for SARS-CoV-2. After a nursing staff tested positive

in day care area, PPE used while managing day care patients was

modified with no further cases noted. Two nursing staff working

in the emergency room tested SARS-CoV-2 positive.

|

|

Fig. 3 Likely source of

SARS-CoV-2 transmission to healthcare workers.

|

Amongst positive staff with likely community

acquired transmission (Fig. 3), 21% (4 out of 19) had

history of SARS-CoV-2 positive contact and 37% (7 out of 19)

travelled by public transport. Nearly one fourth of SARS-CoV-2

positive staff were returning from home leave (10 out of 42) and

almost all were asymptomatic at the time of testing (Fig. 3).

DISCUSSION

The present study analyses the transmission

dynamics of the first HCW cohort from India. In a pediatric

cohort, risk of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 carriage is com-pounded

by presence of caregivers. Other risk factors for HCW exposure

include inadequate social distancing between employees and

non-compliance of mask wearing during breaks [8].

Contact tracing for a SARS-CoV-2 positive

HCWs, showed that 2 staff had to be quarantined for having lunch

together. Cafeteria tables were re-arranged to ensure not more

than 2 people could sit at a table at a time at adequate

distance and leaflets emphasising social distancing amongst HCWs

were put up in the staff cafeteria. HCWs were encouraged to have

meals on their own in their respective areas whenever possible,

which was similar to Contejean, et al.

[9]. This significantly reduced the

incidence of high risk exposure amongst HCWs during meals.

Clustering of cases seen in blood bank were considered hospital

acquired as individuals were on same shift and hence in contact.

Zheng, et al. [2] had an incidence of 7.3%

clinical HCWs being SARS-CoV-2 positive and 2.8% of non-clinical

staff. In our cohort, we had similar findings with 2%

non-clinical staff being SARS-CoV-2 positive emphasising the

need of testing non-clinical symptomatic staff (Fig. 2).

Non clinical staff access common areas and testing all staff

groups has key infection control implications. Doctors were

least positive in our cohort.

Twenty percent (8 out of 42) SARS-CoV-2 of

HCWs were positive as a consequence of sharing rooms in the

hostel with a SARS-CoV-2 positive staff despite immediate

isolation of HCWs at symptom onset indicating transmission of

the virus before onset of symptoms. Our findings were similar to

He, et al. [10], who reported that 9% of transmission could

occur 3 days prior to symptom onset and presymptomatic

transmission to be 44%. Nearly one fourth of SARS-CoV-2 positive

staff were returning from home leave and almost all were

asymptomatic at the time of testing. Though highly debatable, we

preferred testing HCWs returning from home leave in view of high

incidence of community transmission during the first few months

of the pandemic. Testing policy on re-joining work was modified

as per community transmission dynamics. HCWs who preferred

travelling by public transport to the hospital had increased

community exposure. Almost 70% of SARS-CoV-2 positive staff had

likely community acquisition with 7 out of 19 (37%) travelling

by public transport and 4 out of 19 (21%) having a contact

history with a positive case in the community.

Implementing infection prevention and control

(IPC) policies can be challenging during a pandemic but in

studies where reinforcement of IPC measures was done, the curve

flattened in HCWs despite ongoing exposure to COVID-19 patients

[8,9].

We improvised infection control measures and

reinforced basic preventive measures throughout the pandemic. In

presence of adequate PPE and good adherence to infection control

practices, nosocomial acquisition or transmission was less

likely, similar to previous reports [2,11]. HCWs face a

significant risk of SARS-CoV-2 exposure while providing care to

suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patients. It is though important

to remember that transmission may occur in non-patient-care

areas while having meals or talking or from the community. Lack

of adequate PPE, inpatients caregivers, high risk departments,

long duty hours and suboptimal hand hygiene have been linked to

COVID-19 infections in HCWs in various studies [12]. Hand

hygiene, inpatient caregivers and duty hours could have

confounded our findings. Doctors tested least positive in our

study which is similar to Zheng, et al. [2]. Doctors in highly

specialized roles who cannot be replaced by other colleagues,

may continue working with mild and non-specific symptoms, which

is a limiting factor in our study too.

Ethics approval: IEC, SRCC-CH; R-202019,

November, 2020.

Contributors: AP, SU: designed the

retrospective study and wrote the manuscript; MB: wrote the

contact tracing guidelines for HCWs; SS, SK: were involved in

testing and tracing positive HCWs. All authors approved the

final version of manuscript, and are accountable for all aspects

related to the study.

Funding: None; Competing interests:

None stated.

|

WHAT THE STUDY ADDS?

• Most SARS-CoV-2 positive healthcare

workers had likely community transmission with public

transport being a possible high-risk exposure.

• Testing nonclinical symptomatic

staff is essential to reduce transmission as they share

common areas.

|

REFERENCES

1. Huang CL, Wang YM, Li XW, et al. Clinical

features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in

Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020 [Epub ahead of print]. doi:

10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5.

2. Zheng C, Hafezi-Bakhtiari N, Cooper V, et

al. Character-istics and transmission dynamics of COVID-19 in

health-care workers at a London teaching hospital. J Hosp Infect.

2020;106:325-29.

3. Wehrhahn MC, Robson J, Brown S, et al.

Self-collection: An appropriate alternative during the

SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. J Clin Virol. 2020;128:104417.

4. Rivett L, Sridhar S, Sparkes D, et al.

Screening of health-care workers for SARS-CoV-2 highlights the

role of asymptomatic carriage in COVID-19 transmission. Elife.

2020;9:e58728.

5. MOHFW advisory for managing HCWs working

in COVID and non- COVID areas of the hospital. Accessed May 15,

2020. Available from:https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/Advisoryformanag

ingHealthcareworkersworkingin COVIDandNonCOVID

areasofthehospital.pdf.

6. MOHFW COVID-19: Guidelines on rational use

of Personal Protective Equipment. Available from:

https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/GuidelinesonrationaluseofPerso nal

ProtectiveEquipment.pdf.

7. MCGM stop coronavirus in Mumbai, Daily

updates. Available from: https://stopcoronavirus.mcgm.gov.in.

8. Çelebi G, Piskin N, Çelik Bekleviç A, et

al. Specific risk factors for SARS-CoV-2 transmission among

healthcare workers in a university hospital. Am J Infect

Control. [Epub ahead of print]. 2020:S0196655320307653. doi:

10.1016/j.ajic.2020.07.039

9. Contejean A, Leporrier J, Canoui E, et al.

Comparing dynamics and determinants of SARS-Cov-2 transmissions

among healthcare workers of adult and pediatric settings in

Central Paris. Epidemiology. 2020.doi: 10.1101/2020.

05.19.20106427

10. He X, Lau EHY, Wu P, et al. Temporal

dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19.

Nat Med 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0869-5.

11. Wee LE, Sim XYJ, Conceicao EP, et al.

Containment of COVID-19 cases among healthcare workers: The role

of surveillance, early detection, and outbreak management.

Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020:1-7. [Epub ahead of

print]

12. Sahu AK, Amrithanand VT, Mathew R, et

al. COVID-19 in health care workers – A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38:1727-731.

|

|

|

|

|