|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2021;58:542-547 |

|

Effectiveness of

Child-To-Child Approach in Preventing Unintentional Childhood

Injuries and Their Consequences: A Non-Randomized

Cluster-Controlled Trial

|

|

Bratati Banerjee, Rupsa Banerjee, GK Ingle, Puneet Mishra, Nandini

Sharma, Suneela Garg

From Department of Community Medicine, Maulana Azad Medical

College, New Delhi.

Correspondence to: Dr Rupsa Banerjee, Senior Consultant,

Community Processes/Comprehensive Primary Health Care Division, National

Health Systems Resource Centre, NIHFW campus, Block F, Munirka, New

Delhi 110 067, New Delhi, India. Email:

[email protected]

Received: May 14, 2020;

Initial review: June 02, 2020;

Accepted: February 16, 2021.

Published online: February 19, 2021;

PII: S097475591600291

Trial registration: CTRI/2018/07/014872

|

Background: Child-to-child approach is an innovative strategy for

preventing and reducing the morbidity and mortality burden of

unintentional childhood injuries.

Objectives: To test effectiveness of

Child-to-child Approach in preventing unintentional childhood injuries

and their consequences.

Study design: Community-based non-randomized

cluster-controlled trial of parallel design.

Participants: 397 children and adolescents.

Intervention: Eldest literate adolescent of

selected families of intervention area were trained on prevention of

injuries. They were to implement the knowledge gained to prevent

injuries in themselves and their younger siblings and also disseminate

this knowledge to other members of their families.

Outcome: Data was collected from both

intervention and control areas during pre- and post-intervention phases

on the magnitude of injuries, time for recovery from injuries, place for

seeking treatment, cost of treatment, knowledge and practice of

participants and their families regarding injuries.

Results: During post-intervention phase, the

intervention group experienced a significant reduction in incidence of

injuries, increased preference for institutional treatment of injuries

and increased knowledge and practice regarding injuries, in com-parison

to its pre-intervention data and data of the control group in

post-intervention phase. Total time for recovery and cost of treatment

for injuries also decreased in intervention group in post-intervention

phase, though differences were not statistically significant.

Conclusion: Child-to-child approach is effective

in reducing childhood injuries, improving choice of place for seeking

treatment, increasing knowledge of participants, improving family

practices regarding prevention of injuries and reducing expenditure on

treatment of childhood injuries.

Key words: Accident, Educational intervention, Prevention,

Trauma.

|

|

With a change in

epidemiological pattern

of disease burden in the population,

injuries are rising and contributing to a

major part of morbidity and mortality in the entire population,

including children. Childhood injury is currently an alarming

problem in the world. Injuries constitute a large proportion of

global burden of childhood death, particularly for older

children in whom it accounts for almost half of the deaths.

Analysis conducted using Global Burden of Diseases data revealed

that unintentional injuries accounted for 18% of the estimated

deaths among children between the ages of 1 and 19 years

globally [1] and 11.2% of total DALY’s lost in all age groups

[2]. Cost incurred by families towards treatment of childhood

injuries is also enormous around the world [3].

Strategies need to be worked out and

implemented for prevention and control of the problem of

unintentional childhood injuries. Child-to-child approach is one

such innovative strategy [4], which has earlier been proved to

be effective in health promotion among children [5-8]. However,

this approach has not been tested for prevention and control of

injuries in children.

The study was conducted with the objective of

assessing the effectiveness of child-to-child approach in

preventing unintentional childhood injuries and their

consequences in terms of time taken for recovery and cost

incurred on treatment.

METHODS

A community based non-randomized

cluster-controlled trial of parallel design was conducted in

rural area of Delhi. The study was approved by the Institutional

Ethics Committee and written informed consent was taken from

heads of the families and consent/assent was taken from all

participants as applicable.

The study area comprised of one intervention

and one control village in North-West Delhi, which were widely

separated from each other with another habitation located in

between, to prevent contamination. The villages for intervention

and control groups were selected by purposive sampling

considering logistic and operational feasibility. The main study

was undertaken from August, 2017 to January, 2019 and comprised

of 7 broad phases – recruitment, pre-intervention, intervention,

reinforcement, washout, post-intervention and

intervention in control group.

For operational purposes, injury was defined

as physical damage to the child’s body, caused unintentionally/accidentally.

‘One injury’ was defined as each injury of a different type or

in different body part occurring in a child, even if occurring

at the same time due to the same cause. ‘One injury event’ was

defined as one child injured at one point of time, even if it

resulted in multiple injuries.

Children and adolescents aged 0-19 years

belonging to families having at least one adolescent and two

younger siblings were included in the study. Mentally deranged

or critically ill participants were excluded from the study.

Consecutive families were selected for wide dissemination of the

message which is the crux of child-to-child approach.

Recruitment was done at the initiation of the study.

Sample size calculation was based on a pilot

study which was conducted in a different part of the study area;

50 children aged 0-19 years with a recall period of 3 months

were evaluated and the incidence of injury was observed as 15%.

Expecting a 5% reduction in incidence of injury after the

intervention and keeping alpha and beta errors at 5% and 20%,

respectively, sample size was estimated as 90 as per the WHO

guidelines [9] for a two-sided hypothesis test for an incidence

rate, when the observations are censored at 4 months. As the

study required more than one child from one family for

implementing child-to-child approach, clustering effect was

likely to occur due to similarity of participants within a

family. Keeping this in view and to adjust for design effect,

calculated sample size was multiplied by a factor of 2, making a

size of 180 children. Since the study required follow-up of 20

months, possibility of non-response/attrition was considered and

hence 10% was added to this and rounded off to final sample size

of 200 participants each in intervention and control group.

Training was given to the eldest adolescents

in the families of intervention area during intervention phase

i.e., January-April, 2018. Eldest adolescents of the families of

the control area were trained after the completion of data

collection in post-intervention phase. Eligible adolescents

were trained on various aspects of injuries and their

prevention. Training included three components: (i) First

aid and cardio-pulmonary resuscitation (CPR) by St. John’s

Ambulance Services of Indian Red Cross Society, (ii) road

safety and traffic rules as collaboration between Delhi Traffic

Police and Hero MotoCorp, Hero Honda and (iii) injury

prevention and immediate care by the research team. In addition,

messages were given regularly to adolescents during home visits

for data collection. At the end of training, the trained

adolescents were each given a module highlighting salient points

covered in the trainings regarding common injuries and their prevention, a first aid kit and a box with child lock for safe

storage of items likely to cause injury. Trained adolescents

were told to be vigilant and thus prevent occurrence of injuries

in themselves and their younger siblings. They were also

encouraged to pass on the knowledge they had gained through

trainings to their adolescent siblings and all adult women in

their families including mothers, aunts, grandmothers, elder

sisters or sisters-in-law. Subsequently, weekly visits were made

and reinforcement of information was done for 2 months

(May-June, 2018), followed by washout period of 2 months

(July-August, 2018). Control group was also visited at similar

frequency and interval, but only general health messages were

given with no special mention regarding injuries.

Data was collected using a pre-tested

semi-structured proforma, during pre- and post-intervention

phases of four months each, in same months of the year,

pre-intervention data being collected during September-December,

2017 and post-intervention data collected during

September-December, 2018. Ongoing data collection regarding

injury events continued during intervention, reinforcement and

washout phases. Each family was visited once a week during data

collection periods and details regarding injuries that had

occurred in the previous week were enquired into. Families were

also given a notebook each and were told to note down the

relevant details which were assessed by the field investigators

at their subsequent weekly visit and cross-checked by

investigators. Data variables included details about injuries

that occurred, time for recovery from the injury, health care

facility availed for treatment and expenditure incurred for

treatment. Expenditure incurred for treatment for all injury

events included doctor’s consul-tation fee, medicines,

investigations, operations, bed charges, expenses for travel and

expenses for accom-panying person. Wage loss was also

considered. For calculating cost of treatment in private sector,

information was taken about amount actually paid for availing

services, while that in government sector included the cost of

medicines, investigations and procedures as calculated on the

basis of rate contract of Delhi Government Central Procurement

Agency for medicines and the amount pres-cribed for

reimbursement for investigations and procedures under Delhi

Government Employees’ Health Scheme. In addition, the field

investigators during their weekly visits distributed medications

for symptomatic treatment under guidance of investigators of

this research.

Prior to the intervention, baseline knowledge

of participants and practice of families as reported by

participants was assessed by interview of adolescents eligible

for training, all other adolescents and all women aged 20 years

and above of the families. Family practice was assessed as

reported by respondents, on two aspects i.e. measures taken for

prevention of injuries and treatment seeking behavior in case of

occurrence of injuries. Each response was scored and the total

knowledge and practice (KAP) score was calculated. Maximum

attainable score was 29 for knowledge, 60 for practice and 89

for total KAP score. Higher score implied better knowledge and

safer practice.

Statistical analysis: Primary

outcome measure was magnitude of injuries, while secondary

outcome measures included time taken for recovery from injuries,

choice of health facility for treatment of injuries, cost for

treatment of injuries, knowledge of participants and practice of

families regarding injuries and their prevention. Comparison was

made between data of intervention and control groups during

pre-intervention phase to establish matching, pre- and

post-intervention phases of intervention group to assess changes

following intervention, and intervention and control groups

during the post-intervention phase to establish that changes

occurred mainly due to the intervention. For all comparisons,

t test for difference between means and z test for

difference between pro-portions were used for quantitative and

qualitative data, respectively. Chi-square test with Yates

correction was done for comparison of health care facility

availed. For comparison of mean and median cost, Mann Whitney U

test and median test were done, respectively. P value of

<0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

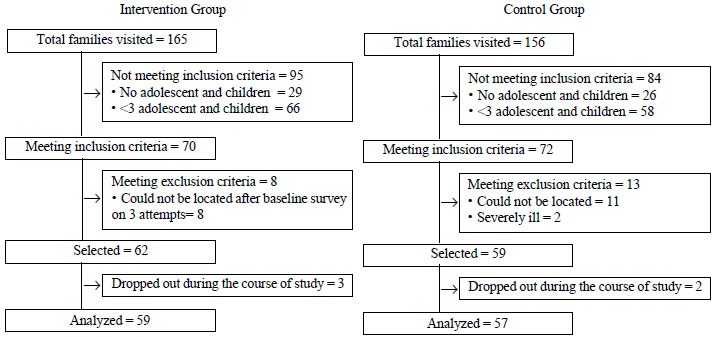

We included 197 and 200 participants each in

the 59 and 57 families, respectively of the intervention and

control groups. Recruitment of participants is shown in Fig.

1. Participants in both the areas were comparable in terms

of sociodemographic profile.

|

|

Fig. 1 Flow chart showing

recruitment of participants based on eligibility

criteria.

|

Throughout the period of study there was no

fatal injury and none of the injured participants required

hospital admission. Table I shows the incidence of

injuries in the two areas. Annual and monthly incidence of

injury events were calculated as number of injury events

occurring per 100 children per year or month as applicable.

Annual incidence of injury events in the total participants was

32.24 per 100 children per year with average monthly incidence

of 2.69% (2.62 in intervention group and 2.75 in control group),

with no statistically significant difference between the two

groups. In the intervention group, the monthly incidence dropped

significantly in post-intervention phase. Though monthly

incidence had dropped slightly in control area also in the

post-intervention phase, it was still significantly higher than

that in intervention group.

Table I Total Injury Events and Monthly Incidence in the Participants in the Intervention and Control Groups

| Phase of study |

Intervention group (n=197) |

Control group (n=200) |

P value |

Total (N=397) |

| Pre-intervention |

25, 3.17 (0.72-5.6) |

26, 3.25 (0.79-5.7) |

0.86 |

51, 3.21 (1.48-4.9) |

| Post-intervention |

16, 2.03 (0.06-4.0) |

29, 3.62 (1.03-6.2) |

<0.001 |

45, 2.83 (1.2-4.46) |

|

Annual incidents of injuriesa |

62, 31.47 (24.9-37.9) |

66, 33.00 (26.5-39.5) |

0.74 |

128, 32.24 (27.6-36.8) |

| Data expressed as total

injury events, monthly incidence (95% CI). P=0.009 for

pre- and post-intervention periods in intervention group

and P=0.0002 for post-intervention period in

intervention and control groups. aIncludes injuries that

occurred from September, 2017 to August, 2018. |

Table II Type of Health Facility Attended for Treatment of Injury Events

| Type of facility |

Intervention group |

|

|

Control group |

|

Pre-intervention |

Post-intervention |

Pre-intervention |

Post-Intervention |

|

(n=25) |

(n=16) |

(n=26) |

(n=29) |

| Hospital/health centre/clinic |

6 (24.0) |

13 (81.3) |

3 (11.5) |

4 (13.8) |

| RMP/FI/OTC/ home/none |

19 (76.0) |

3 (18.7) |

23 (88.5) |

25 (86.2) |

| Data in no. (%). RMP:

registered medical practitioner; OTC: over the counter. |

The mean time taken for recovery from

injuries in total study participants, which included the total

duration for the wound to heal/ medicines to be stopped/ normal

activities to be resumed (as applicable on a case-to-case

basis), was similar in the two groups in the pre-intervention

phase (P=0.58). Both the intervention group [5.7 (2.4) vs

5.9 (2.9); P=0.79] and control group [7.8 (19.0) vs 7.0

(4.5); P=0.82] did not show any significant differences

in their respective pre- and post-intervention time for

recovery. Total time for recovery from all injuries had reduced

in post-intervention phase in intervention group (143 vs 95

days), while it remained same in control group in both phases

(204 days).

Table II shows the choice of health care

facility by the families for treatment of injuries. Families had

taken treatment from government or private hospital/health

center/clinic, registered medical practitioners (RMP),

over-the-counter treatment by buying medicines from the pharmacy

without consulting a doctor, and home treatment. In the

pre-intervention phase, majority of injured participants in both

groups (>75%) had taken treatment from unqualified providers,

which decreased to 18.1% in the intervention group in

post-intervention phase, in contrast to 86.2% participants in

the control group (P<0.001) (Table II).

The total and the median (IQR) cost of

treatment for injuries in the intervention group decreased from

Rs. 5962.9 to Rs 4949.5, and Rs 90 (102.5) to Rs 19.8 (116.28),

respectively (P=0.84). The corresponding values in

control group were Rs 4734.5 and Rs 7013.4 and Rs. 46.5 (153.75)

and Rs. 40 (135.31), respectively. These differences were

statistically insignificant. The post-intervention median costs

in intervention arm and control arm were comparable.

Table III Knowledge and Practice Scores Regarding Injuries in the Study Groups

|

Intervention group |

|

|

|

|

Control group |

|

No. |

Pre-intervention |

Post-intervention |

No. |

Pre-intervention |

Post-intervention |

| Adolescents for training |

59 |

|

|

57 |

|

|

| Knowledge |

|

8.8 (1.9) |

11.6 (2.6) |

|

9.0 (1.9) |

9.0 (1.6) |

| Practice |

|

39.6 (4.9) |

47.5 (4.8) |

|

37.9 (5.7) |

41.2 (3.7) |

| Total score |

|

48.5 (5.3) |

59.1 (6.4) |

|

46.9 (6.6) |

50.3 (4.2) |

| Other adolescents |

93 |

|

|

81 |

|

|

| Knowledge |

|

7.9 (2.2) |

9.8 (2.3) |

|

8.5 (1.7) |

8.4 (1.4) |

| Practice |

|

38.4 (3.9) |

47.0 (5.2) |

|

37.5 (4.3) |

41.1 (3.8) |

| Total score |

|

46.4 (4.8) |

56.8 (6.5) |

|

46.0 (5.0) |

49.5 (4.2) |

| Adult women |

93 |

|

|

86 |

|

|

| Knowledge |

|

8.0 (1.7) |

10.5 (2.3) |

|

8.2 (1.6) |

8.7 (1.5) |

| Practice |

|

40.4 (4.7) |

48.4 (4.1) |

|

41.4 (4.6) |

44.2 (4.1) |

| Total score |

|

48.5 (5.4) |

58.8 (5.3) |

|

49.6 (5.2) |

52.9 (4.6) |

| Scores expressed as

mean (SD). Data were compared for knowledge scores,

practice scores and total scores for all three groups

viz., adolescent for training, other adolescents and

adult women. For comparison of pre-intervention data of

intervention and control groups, all P>0.05; for pre-

and post-intervention data of intervention group, all

P<0.001; for post-intervention data of

intervention and control groups, all P<0.001. |

Table III depicts the KAP scores of all

three groups of participants. These scores were similar for all

participants during the pre-intervention phase. Mean scores in

all aspects had improved considerably during post-intervention

phase in all participants in the intervention area. Scores had

improved slightly in all groups of control area also. KAP scores

in all groups of participants between pre- and post-intervention

phases in intervention area and between post-intervention phases

in both areas showed statistically significant differences,

indicating dissemination of safety messages.

DISCUSSION

This community based non-randomized

cluster-controlled trial of parallel design was conducted in

rural area of Delhi, to test the effectiveness of child-to-child

approach by training the eldest adolescent members of the

families for preventing unintentional childhood injuries in

themselves and their younger siblings. During post-intervention

phase, the intervention group experienced statistically

significant reduction in incidence of injuries, improvement in

preference for health facilities for seeking treatment, and

increase in knowledge and practice regarding injuries, in

comparison to its pre-intervention data and data of control

group in post-intervention phase. Total time for recovery and

cost of treatment for injuries including out-of-pocket

expenditure also decreased in intervention group in

post-intervention phase, though differences were not

statistically significant.

However, the study had some limitations.

Firstly, a randomized controlled trial could not be done as

study design required consecutive families be included for

dissemination of information and blinding also could not be done

due to obvious reasons. Secondly, the pre- and post-intervention

data collection periods were short due to operational

feasibility. Since data regarding injury and treatment details

was self-reported, these may have been under-reported although

efforts to minimize the same were done by asking participants to

record the events in notebooks which were assessed on a weekly

basis by the research team. Strengths of the study included a

good follow up with an attrition rate of only 4.6%. Frequent

visits by field investigators also resulted in a good rapport-

building and ensured cooperation from the community. A control

group was used that resulted in drawing valid conclusions

regarding outcome. The study groups of both areas at the time of

recruitment were matching in all characteristics of the study

participants and families. Extensive trainings could be given to

the adolescents, two of those being formal trainings from

professional organi-zations. Pre- and post-intervention data

were collected during the same months of the year to rule out

the chance of seasonal variation. Data regarding injuries was

collec-ted by weekly house visits and hence recall period being

very short ensured good quality of data.

Childhood injury is an area of concern in the

entire world, including India. Studies conducted on childhood

injuries in India and abroad have reported various levels of

magnitude [10-20]. Higher annual incidence observed in the

present study was due to weekly active surveillance undertaken

that could capture even minor injuries which are usually

attended at home and hence remain unreported to the health

system. To prevent and control such an alarming problem, various

researchers have reported success of implementing intervention

measures as part of their research on home injury hazards [21],

first aid [5,6], nutrition [7] and health education in general

[8]. Inter-vention in some of these studies was by

implementation of child-to-child approach [5-8]. Though two of

these studies were on improving knowledge regarding injuries and

first aid, there was no study using this approach on injury

pre-vention or cost reduction. Slight decrease in incidence of

injuries and increase in KAP score was obser-ved in the control

area also, probably due to increased awareness through repeated

visits and enquiry regarding injury occurrence.

The present study highlights the need for

introduction of safety education in school curriculum to make

children aware of injuries, their consequences and methods of

prevention. Training on first aid and CPR may be made compulsory

in all schools and colleges, with regular mock drills for injury

management in educational institutions, occupational

institutions and community. Child-to-child program needs to be

implemented by training older adolescents in schools,

encouraging them to take care of their younger siblings at home

and disseminate the messages widely. It can also be implemented

by integrating with other community based health programs and

delivered through primary health care platforms, which will go a

long way in combating the problem of unintentional childhood

injuries in the country.

Acknowledgements: St. John’s Ambulance

Services of Indian Red Cross Society, Delhi Traffic Police and

Hero MotoCorp, Hero Honda, for conducting trainings.

Ethical clearance: Institutional

Ethics Committee, Maulana Azad Medical College; No.

IEC/MAMC/(56)/2/2017/No 74, dated 17 May, 2017.

Contributors: BB contributed to designing

the study, analyzing and interpreting the data, and drafting the

manuscript; RB contributed to analyzing data, and drafting the

manuscript; GKI contributed to designing the study and revising

the manuscript; PM contributed to acquiring and analyzing data;

NS contributed to analyzing data and revising the manuscript; SG

contributed to analyzing data and revising the manuscript. All

authors approved the final manuscript and agreed to be

accountable for the work.

Funding: Indian Council of Medical

Research, New Delhi; Competing interest: None stated.

|

|

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN?

•

Implementation of

child-to-child approach is an effective way to improve

awareness of school children regarding unintentional

childhood injury and first aid.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS?

•

Child-to-child approach is effective in reducing

number of injury events, total time for recovery from

injuries, cost for treatment of injuries and

out-of-pocket expenses of families, as well as in

improving knowledge of participants and practice of

families regarding injury prevention and control.

|

REFERENCES

1. Alonge O, Hyder AA. Reducing the global

burden of childhood unintentional injuries. Arch Dis Child.

2014; 99:62-9.

2. Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M,

Flaxman AD, Michaud C. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs)

for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: A

systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Study 2010. Lancet.

2012;380:2197-223.

3. Lao Z, Gifford M, Dalal K. Economic cost

of childhood unintentional injuries. Int J Prev Med.

2012;3:303-12.

4. Child to child. Our history [Internet].

2019. Accessed on 16 August, 2020. Available from:

http://www.childtochild. org.uk/about/history/

5. Elewa AAA, Saad AM. Effect of child to

child approach educational method on knowledge and practices of

selected ûrst aid measures among primary school children. J Nurs

Educ Pract. 2018;8:69-78.

6. Muneeswari B. A study to assess the

effectiveness of planned health teaching programme using

child-to-child approach on knowledge of selected first aid

measures among school children in selected schools at Dharapuram

in Tamil Nadu, India. Glob J Med Public Health. 2014;3:18.

7. Sajjan J, Kasturiba B, Naik RK, Bharati

PC. Impact of child to child nutrition education intervention on

nutrition knowledge scores and hemoglobin status of rural

adolescent girls. Karnataka J Agric Sci. 2011;24:513-5.

8. Leena KC, D’Souza SJ. Effectiveness of

child to child approach to health education on prevention of

worm infes-tation among children of selected primary schools in

Man-galore. Nitte Univ J Health Science. 2014;4:113-5.

9. Lwanga SK, Lemeshow S. Sample size

determination in health studies: A practical manual. World

Health Organi-zation; 1991. Accessed on 16 August, 2020.

Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/40062/9241544058_%28p1-p22%29.pdf?sequence=1&is

Allowed=y

10. Parmeswaran GG, Kalaivani M, Gupta SK,

Goswami AK, Nongkynrih B. Unintentional childhood injuries in

urban Delhi: A community-based study. Indian J Community Med.

2017;42:8-12.

11. Mathur A, Mehra L, Diwan V, Pathak A.

Unintentional childhood injuries in urban and rural Ujjain,

India: A community-based survey. Children 2018;5:23.

12. Kamal NN. Home unintentional non-fatal

injury among children under 5 years of age in a rural area, El

Minia Governorate, Egypt. J Community Health. 2013;38:873-9.

13. Thein MM, Lee BW, Bun PY. Childhood

injuries in Singa-pore: a community nationwide study. Singapore

Med J. 2005;46:116-21.

14. Lasi S, Rafique G, Peermohamed H.

Childhood injuries in Pakistan: results from two communities. J

Health Popul Nutr. 2010;28:392-8.

15. Howe LD, Huttly SRA, Abramsky T. Risk

factors for injuries in young children in four developing

countries: the Young Lives Study. Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11:

1557-66.

16. Chalageri VH, Suradenapura SP, Nandakumar

BS, Murthy NS. Pattern of child injuries and its economic impact

in Bangalore: a cross-sectional study. National J Community

Medicine. 2016;7:618-23.

17. Mohan D, Kumar A, Varghese M. Childhood

injuries in rural North India. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot.

2010;17: 45-52.

18. Shriyan P, Prabhu V, Aithal KS, Yadav UN,

Orgochukwu MJ. Profile of unintentional injury among under-five

children in coastal Karnataka, India: A cross-sectional

study.Int J Med Sci Public Health. 2014;3:1317-9.

19. Bhuvaneswari N, Prasuna JG, Goel MK,

Rasania SK. An epidemiological study on home injuries among

children of 0-14 years in South Delhi. Indian J Public Health.

2018;62:4-9.

20. Cameron CM, Spinks AB, Osborne JM, Davey

TM, Sipe N, McClure RJ. Recurrent episodes of injury in

children: an Australian cohort study. Austr Health Rev.

2017;41:485-91.

21. Chandran A, Khan UR, Zia N, et al.

Disseminating childhood home injury risk reduction information

in Pakistan: results from a community-based pilot study. Int J

Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10:1113-24.

|

|

|

|

|