|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2021;58:537-541 |

|

Effectiveness of

School-Based Interventions in Reducing Unintentional Childhood

Injuries: A Cluster Randomized Trial

|

|

Ramesh Holla 1, BB Darshan1,

Bhaskaran Unnikrishnan1,

Nithin Kumar1, Anju Sinha2,

Rekha Thapar1,

P Prasanna Mithra1, Vaman

Kulkarni1, Archana Ganapathy1,

Himani Kotian1

From Departments of 1Community Medicine, Kasturba Medical College,

Mangalore (Manipal Academy of Higher Education), Karnataka; and

2Division of Reproductive, Maternal and Child Health, Indian Council of

Medical Research, Ansari Nagar, New Delhi.

Correspondence to: Dr Ramesh Holla, Associate Professor, Department

of Community Medicine, Kasturba Medical College, Mangalore (Manipal

Academy of Higher Education), Karnataka, India.

Email:

[email protected]

Received: November 09, 2020;

Initial review: December 15, 2020;

Accepted: February 04, 2021

Published online:

February 19, 2021;

PII: S097475591600292

Trial registration: CTRI/2018/02/011765

|

Objective: To evaluate the effectiveness of

school-based interventions in promoting child safety and reducing

unintentional childhood injuries.

Methods: This cluster randomized trial with 1:1

allocation of clusters to intervention and control arm was conducted in

the public and private schools of Dakshina Kannada district, Karnataka,

over a period of 10 months. Study participants included children from

standard 5-7 in schools selected for the study. 10 schools that

could accommodate 1100 students each, were randomly allocated to the

interventional and control arm. A comprehensive child safety and

injury prevention module was developed based on the opinions of school

teachers through focus group discussions. This module was periodically

taught to the students of intervention arm by the teachers. The children

in control arm did not receive any intervention. Outcome was assessed by

determining the incidence of unintentional injuries and type of injuries

from the questionnaire used at the baseline, and at the end of three,

six, and ten months.

Results: Unintentional injuries declined

progressively from baseline until the end of the study in both the

interventional arm (from 52.9% to 2.5%) and control arm (from 44.7% to

32%) [AOR (95% CI) 0.458 (0.405-0.518); P value <0.001]. The

decline in incidence of injuries in the interventional arm was higher

than that in the control arm (50.4% vs 12.7%; P <0.001).

Conclusion: School based educational intervention

using child safety and injury prevention modules is effective in

reducing unintentional injuries among school children over a 10-month

period.

Keywords : Education, Fall, Prevention, School health.

|

|

U nintentional injuries

specifically cause up to

950,000 deaths among children under 18

years annually [1] and more than half of

these deaths are reported from Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia

[2]. Aside from mortality, accidental injuries can also lead to

long-lasting emotional, physical, behavioral and developmental

disabilities in children, which in turn could adversely affect

the health and socio economic aspects of a nation [3].

Prevention of injuries has been classified

into three strata of primary, secondary and tertiary prevention,

as per a model suggested by World Health Organization [4]. The

above-suggested WHO model can be incorporated while designing an

effective school-based injury-prevention program. This can be

used to address the policies and procedures, capacity building

of school teachers, the physical environment of the school, and

the curriculum in a coordinated manner.

There is little existing evidence to prove

that educational interventions alone are sufficient in reducing

the incidence of unintentional injuries [5]. Further studies are

required to evaluate the impact of school-based interventions on

injury occurrence as current studies only show a weak

association between the two [5]. Thus, this study was conducted

to evaluate the effectiveness of school-based interventions in

promoting child safety and reducing unintentional injuries.

METHODS

The study was conducted in the public and

private schools of Dakshina Kannada district, Karnataka, over a

period of 10 months from July, 2017 to March, 2018. It was a

cluster randomized trial with 1:1 allocation of clusters into

intervention arm and control arm, where schools are considered

as clusters. After excluding schools based on their willingness

to participate and existing participation in any child safety

and injury prevention program, randomization of schools was done

to accommodate 10 schools in the intervention arm and 10 schools

in the control arm by simple random method. Due representation

was provided to both public and private schools in both arms.

The study participants included 1100 children from standard 5-7

in the schools selected for the study. We assumed there

would be 40 students in each section of these standards. By

enrolling all the students of a particular section, we would be

enrolling 120 students from each cluster for the study.

Selection of a section for a particular class was done by

adopting simple random technique.

The sample size for the study was calculated

by considering a prevalence of 23% childhood injuries as per a

previous study [6]. The proposed intervention was considered

effective if it reduced the incidence of injury to 15%. Hence,

to account for the 8% reduction as significant at 90% power, 5%

level of significance and at two-sided test, the sample size was

calculated to be 503 in each arm. As it was a cluster-randomized

trial, we presumed a design effect of 2 and the sample size was

1006. As we anticipated a maximum of 10% loss during the

follow-up period of 10 months; the final sample size was

calculated to be 1107 in each arm.

A comprehensive child safety and injury

prevention module was then developed based on the opinions of

school teachers from both urban and rural settings through focus

group discussions. Later, subject experts validated the contents

of the module. This comprehensive pictorial module consisted of

child safety and measures to be taken by the children for the

prevention of unintentional childhood injuries due to road

traffic accidents, fall, burns, drowning, poisoning, animal

related and other domestic causes.

Two teachers (including one physical

training/sports teacher) from each school of the interventional

arm were trained using this module. The teachers then taught the

children on a periodic and regular basis for the duration of the

study, using an instruction manual for modular teaching (25-30

hours on an average was spent per school). The students in the

control arm received the comprehensive modular training after

the end of the final data collection. While imparting this

modular training, emphasis was given for child safety and injury

prevention strategies to be inculcated by the children.

The tool used for data collection was a

semi-structured questionnaire developed based on World Health

Organization guidelines for conducting community surveys on

injuries and violence [7]. This captured the incidence of

unintentional injuries and the type of injuries among

schoolchildren of both arms in the preceding three months. The

same questionnaire was administered for both the groups at

baseline, and at three, six, and ten months of the study.

Outcome was assessed by the same set of investigators at each

point of time in both intervention and control arm students.

Clearance was obtained from the institutional

ethics committee and permission was taken from the Block

Education Office. Due clearance was also obtained from the

school principals where the study was conducted. As the study

participants were children younger than 18 years, a written

informed consent was obtained from their parents before

enrolment into the study. Assent from the students were also

obtained. Confidentiality and anonymity was maintained

throughout the study.

Statistical analysis: All the data

collected in the field were managed at the central coordinating

site. The variables were coded and entered into Statistical

Package for Social Sciences Version 25.0 (IBM Corp). Descriptive

statistics and inferential statistics (Z test for difference in

two proportions, and generalized estimation equations (GEE) was

used to test the overall effectiveness of the inter-vention

across the groups with time) were used to express the results.

P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

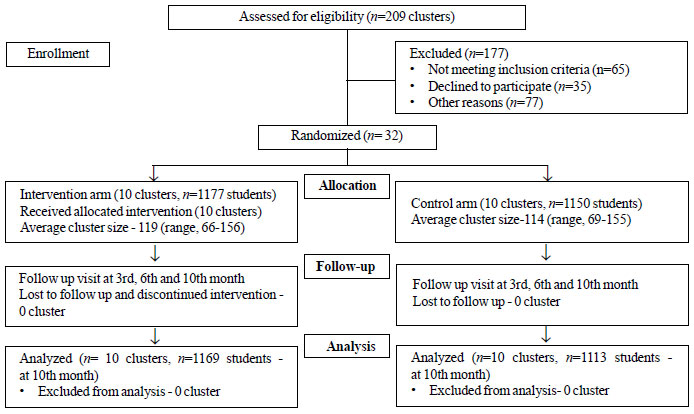

Out of 2327 children who were enrolled into

the study at baseline, 1177 children were in the interventional

arm and 1150 were in the control arm (Fig. 1). The

baseline data is provided in Table I.

|

|

Fig. 1 Flow diagram of the

study.

|

Table I Baseline Characteristics of Study Participants (N=2327)

| Characteristics |

Intervention group |

Control group |

|

(n=1177) |

(n= 1150) |

| Male sex |

658 (55.9) |

500 (43.5) |

| Class |

|

|

| 5th |

367 (31.2) |

362 (31.5) |

| 6th |

306 (26.0) |

501 (43.5) |

| 7th |

504 (42.8) |

287 (25.0) |

| Urban locality |

656 (55.7) |

314 (27.3) |

| Government school |

507 (43.1) |

408 (35.5) |

| Values in no.(%). |

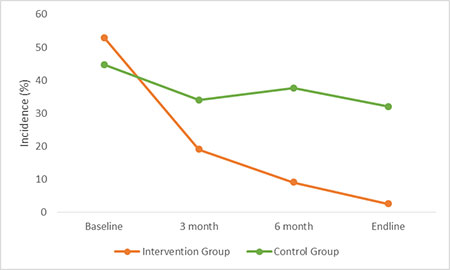

Incidence of unintentional childhood injuries

among schoolchildren of interventional and control group during

the study period is shown in Table II. Nearly half of the

study participants of the intervention (52.9%) and control

(44.7%) group had injuries in the preceding 3 months at the

baseline. The incidence of injuries declined progressively from

baseline until the end of the study among children in both the

groups [Adjusted OR (95% CI) 0.46 (0.40-0.52; P <0.001] (Fig.

2).

Table II Incidence of Unintentional Childhood Injuries

| Unintentional injury |

Intervention group |

Control group |

| Baseline |

623 (52.9) |

514 (44.7) |

| 3 mo |

224 /1179 (19.0) |

382/1123 (34.0) |

| 6 mo |

107/1184 (9.0) |

442/1175 (37.6) |

| End line |

29/1169 (2.5) |

356/1113 (32.0) |

| Incidence based on

generalized estimating equations (GEEs). Values in n/N

(%). Adjusted OR (95% CI)=0.45 (0.40-0.52), P<0.001. |

|

|

Fig. 2 Trends in incidence of unintentional

childhood injuries over 10 months.

|

The extent of decline in incidence of

injuries from the start of the study till the end in the

interventional arm was higher than in the control arm (50.4% vs

12.7%; P<0.001).

Various causes of unintentional childhood

injuries across both groups throughout the duration of the study

is depicted in Suppl. Table I. Fall was the most common

cause of injury among children of interventional (56.8%) and

control group (46.7%) at baseline. Decline in the incidence of

unintentional injuries was observed in both the groups across

all categories.

DISCUSSION

We found that the incidence of unintentional

injuries among students in both the control arm and

interventional arm decreased compared to baseline incidence.

However, the extent of decrease was much greater in the

inter-ventional arm. While comparing incidences in both groups

across specific categories, the number of children who sustained

injuries from road traffic accidents, falls and others decreased

to a larger extent in the interventional group compared to the

control group with the biggest reduction noted in falls.

A randomized pre-test and post-test

comparative design study, ‘Think First for Kids’ [8] conducted

among grade 1, 2 and 3 students, evaluated the outcome of an

injury prevention program. The results of this study showed that

students in the interventional group had lesser self-reported

high-risk behaviors, and increased knowledge about ‘safe’

behaviors to avoid injuries as compared to students in the

control arm. In another study in rural China [9], a multi-level

educational interventional model (open letter about security

instruction distributed to parents, children’s injury-avoidance

poster put up at schools, and multimedia resource-aids for

health education) improved knowledge and safety attitudes among

students in the intervention arm as compared to the control arm.

It is interesting to note that the incidence

of unintentional injuries decreased among children in the

control group as well. We hypothesize that this could be due to

a combination of various factors. This includes the learning

curve of the child after experiencing an unintentional injury

and knowledge gained over time from other sources such as

parents or public health awareness campaigns.

From our study we also noted that the biggest

reduction in unintentional injuries was in the category of falls

among children in the interventional arm. The educational module

imparted knowledge on safe behaviors at home and while playing

outdoors. There were pictorial representations of scenarios

which most-likely lead to falls such as playing on escalator and

climbing trees. Another study by Morrongiello and Matheis [10]

used a similar educational intervention and it was shown to

reduce falls, particularly in the playground, through the

‘practice what you preach’ project. Children had less

risk-taking behavior and more safe practices after the

intervention.

Unintentional injuries due to road traffic

accidents also considerably reduced in the interventional group

as compared to the control group. Pictorial representations of

Dos and Don’ts related to Road safety was used to educate

children every week. Another public school based educational

intervention to improve attitudes, increase knowledge and change

unsafe road practices was implemented in four schools in Mexico

among 219 children and teenagers [11]. A significant improvement

in the attitude, practices and knowledge of involved students

were seen. The number of students suffering from burns decreased

significantly in the interventional group while it remained

constant in the control group, showing the effectiveness of the

educational module in this area. A cluster randomized controlled

trial evaluating an injury prevention program "Risk Watch’ in 20

primary schools among 459 children aged 7-10 years in

Nottingham, UK showed similar results [12]. At the end of this

one-year injury prevention program, it was effective in

increasing few aspects of children’s knowledge of fire and burn

prevention skills, although it had little effect on

self-reported safety behaviors, unlike our study.

The main limitation of our study is that it

is a single centric study and had a short duration of follow-up.

The results obtained regarding the prevention of unintentional

injuries among children using educational interventions cannot

be extrapolated until further multi-centric studies show the

same results. As this school based intervention using child

safety and injury prevention module was found to be effective in

reducing the incidence of unintentional injuries; this modular

intervention can be considered for incorporating it in the

school curriculum, after obtaining evidence from well-planned

multi-centric studies incorpo-rating a longer follow-up.

To conclude, the school based educational

inter-ventions using the child safety and injury prevention

module have significantly reduced the incidence of unintentional

injuries among children in the intervention arm when compared to

students of control arm where such educational interventions

were not given.

Acknowledgements: Mr. Laxminarayana

Acharya and Ms. Mamatha, Medical Social Workers and Ms. Shika J,

Data Entry Operator for successful completion of the project.

Note: Supplementary material related to

this study is available with the online version at

www.indianpediatrics.net

Ethics clearance: Institutional

Ethics Committee of Kasturba Medical College, Mangalore; No. IEC

KMC MLR 12-14/285, dated 17 December, 2014.

Contributors: RH, DB: Concept and design,

analysis, inter-pretation of data, drafting the article; BUK:

Concept and design, interpretation of data, drafting the

article, revising it critically; VK, NK: Interpretation of data,

revising it critically for important intellectual content; RT,

PM: Study design, interpretation of data, revising it critically

for important intellectual content; AS: Revising the manuscript

critically for important intellectual content and critical

interpretation of the data captured; AG: Analysis of the data,

drafting the manuscript and proof reading; HK: Data analysis and

critical revision of the results. All authors approved the final

version of manuscript, and are accountable for all aspects

related to the study.

Funding: Indian Council of Medical Research;

Competing interests: None stated.

|

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS?

• A school-based educational intervention is

effective in reducing the incidence of unintentional

childhood injuries among school children.

|

REFERENCES

1. Orton E, Whitehead J, Mhizha-Murira J, et

al. School-based education programmes for the prevention of

unintentional injuries in children and young people. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev. 2016;12:CD010246.

2. Mahapatra T. Public health perspectives on

childhood injuries around the world: A Commentary. Ann Trop Med

Public Health 2015;8:233-4.

3. Sinha AP, Sarma S, Kamal R, Gupta P,

Amritanshu. Prevention of unintentional childhood injuries in

India: An Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) initiative.

EC Paediatrics. 2020;9:143-48.

4. Barcelos RS, Del-Ponte B, Santos IS.

Interventions to reduce accidents in childhood: a systematic

review. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2018;94:351-67.

5. Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention. School Health Guidelines to Prevent Unintentional

Injuries and Violence. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2001;50:1-73.

6. Mahalakshmy T, Dongre AR, Kalaiselvan G.

Epidemio-logy of childhood injuries in rural Puducherry, South

India. Indian J Pediatr. 2011;78:821-5.

7. Seth D, editor. Guidelines for Conducting

Community Surveys on Injuries and Violence. World Health

Orga-nization. Available from:

https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42975

8. Gresham LS, Zirkle DL, Tolchin S, Jones C,

Maroufi A, Miranda J. Partnering for injury prevention:

evaluation of a curriculum-based intervention program among

elementary school children. J Pediatr Nurs. 2001;16:79-87.

9. Cao BL, Shi XQ, Qi YH, et al. Effect of a

multi-level education intervention model on knowledge and

attitudes of accidental injuries in rural children in Zunyi,

Southwest China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12:

3903-14.

10. Morrongiello BA, Mark L. Practice what

you preach: Induced hypocrisy as an intervention strategy to

reduce children’s intentions to risk take on playgrounds. J

Pediatr Psychol. 2008;33:1117-28.

11. Treviño-Siller S, Pacheco-Magaña LE,

Bonilla-Fernández P, et al. An educational intervention in road

safety among children and teenagers in Mexico. Traffic Inj Prev.

2017;18:164-170.

12. Kendrick D, Groom L, Stewart J, et al.

Risk watch: Cluster randomised controlled trial evaluating an

injury prevention program. Inj Prev. 2007;13:93-8.

|

|

|

|

|