|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2021;58: 517-524 |

|

Descriptive Epidemiology of Unintentional

Childhood Injuries in India: An ICMR Taskforce Multisite Study

|

|

Shalini C Nooyi, 1 KN

Sonaliya,2 Bhavna Dhingra,3

Rabindra Nath Roy,4 P

Indumathy,5 RK Soni,6

Nithin Kumar,7 Rajesh K

Chudasama,8 Ch Satish Kumar,9

Amit Kumar Singh,10 Venkata

Raghava Mohan11

Nanda Kumar BS1 and ICMR

Taskforce on Childhood Injuries*

From 1Ramaiah Medical College, Bangalore, Karnataka; 2GCS Medical

College, Ahmedabad, Gujarat; 3AIIMS, Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh;

4Burdwan

Medical College, Burdwan, West Bengal; 5Vellalar College for Women,

Erode, Tamil Nadu; 6Dayanand Medical College and Hospital, Ludhiana,

Punjab; 7Kasturba Medical College, Mangalore (Manipal Academy of Higher

Education), Karnataka; 8PDU Medical College, Rajkot, Gujarat;

9SRM

University, Sikkim; 10VCSG Medical College, Srinagar, Uttarakhand; and

11CMC, Vellore, Tamil Nadu. *Full list of co-investigators and task

force members provided as annexure.

Correspondence to: Dr Nanda Kumar Bidare Sastry, MS Ramaiah Medical

College, Bangalore, Karnataka, India.

Email:

[email protected]

Received: November 13, 2020;

Initial review: December 31, 2020;

Accepted: March 31, 2021.

|

|

Background: Children 0-14 years

constitute about 31.4% of Indian population, among whom the magnitude

and risk factors of childhood injuries have not been adequately studied.

Objective: To study the

prevalence of and assess the factors associated with unintentional

injuries among children aged 6 month - 18 years in various regions.

Methodology: This multi-centric,

cross-sectional, community-based study was conducted at 11 sites across

India. States included were Gujarat, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Punjab,

Sikkim, Tamil Nadu, Uttarakhand, and West Bengal between March, 2018 and

September, 2020. A total of 2341 urban and rural households from each

site were selected based on probability proportionate to size. The World

Health Organization (WHO) child injury questionnaire adapted to the

Indian settings was used after validation. Information on injuries was

collected for previous 12 months. Definitions for types (road traffic

accidents, falls, burns, poisoning, drowning, animal-related injuries)

and severity of injuries was adapted from the WHO study. Information was

elicited from parents/primary caregivers. Data were collected

electronically, and handled with a management information system.

Results: In the 25751 households

studied, there were 31020 children aged 6 months - 18 years. A total of

1452 children (66.1% males) had 1535 unintentional injuries (excluding

minor injuries) had occurred in the preceding one year. The overall

prevalence of unintentional injuries excluding minor injuries was 4.7%

(95% CI: 4.4-4.9). The commonest type of injury was fall-related (842,

54.8%) and the least common was drowning (3, 0.2%). Injuries in the home

environment accounted for more than 50% of cases.

Conclusions: The findings of the

study provide inputs for developing a comprehensive child injury

prevention policy in the country. Child safe school with age-appropriate

measures, a safe home environment, and road safety measures for children

should be a three-pronged approach in minimizing the number and the

severity of child injuries both in urban and rural areas.

Keywords: Animal-related injuries, Burns,

Falls, Poisoning, Road traffic injuries.

|

|

G lobally, injuries and violence

are major public health problems. Children are at a higher risk for

injuries due to their physical and psychological attributes. Their small

body size and the softness of tissues lead to greater vulnerability for

severe impact. Children’s risk perception is limited, making them more

susceptible to involvement in road accidents, drowning, burns, and

poisoning. Psychological characteristics of children like impulsiveness,

curiosity, experimentation, an inadequate judgment of distance/speed,

and low levels of concentration make them vulnerable to injuries [1].

The precise number of deaths and injuries due to

specific causes or any reliable estimates of injury deaths in India are

not available from a single source. The National Crime Records Bureau

data and a study based on available data reveal that nearly 10-15% of

India’s injury deaths occur among children [2,3]. An examination of

‘years of potential life lost’ indicates that injuries are the second

most common cause of death after 5 years of age in India [2]. While

there are selected studies related to unintentional childhood injuries

from hospital-based data, the true magnitude of the issue with

population-level determinants is mostly lacking.

This study presents the results of a national level

community-based multi-centric task force study of unintentional

childhood injuries in India, commissioned by the Indian Council of

Medical Research (ICMR).

METHODS

This multi-centric community-based cross-sectional

study was conducted at 11 different sites across eight states in India

between March, 2018 and September, 2020. A purposive selection of study

sites was made, ensuring adequate geographical representation. The study

population comprised children aged six months to <18 years from both

rural and urban areas viz. Siddlaghatta, Bangalore, Karnataka; Pauri

Garhwal, Srinagar, Uttarakhand; Vellore, Tamil Nadu; Perundurai, Erode,

Tamil Nadu; Mangalore, Karnataka; Bardhman Sadar North, Bardhman, West

Bengal; Dhoraji, Rajkot Gujarat; East Sikkim, Sikkim; Dholka, Ahmedabad,

Gujarat; East Ludhiana, Ludhiana, Punjab; Huzur, Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh

(Fig. 1).

|

|

|

Fig. 1 Map of India with location of

participating institutions and study sites.

|

Sample size and sampling strategy: The

sample size was calculated considering the overall prevalence of

childhood injuries to be 11.0% (including minor injuries) as per the

guidelines for conducting community surveys on injuries and violence by

WHO [4], with a relative precision of 13% and 95% desired confidence

level, with increase in sample size by 10% to allow for non-responses,

design effect of 2 to account for cluster sampling and relative

precision of 13%. Hence, 2341 households from rural and urban areas

(combined) were selected from each site proportionately based on the

population’s rural-urban distribution as per 2011 census [5]. In each

site, the district predominantly served by the participating institution

was selected. Subsequently, one taluk was selected through a simple

random sampling technique. Applying probability proportionate to size

(PPS) sampling, within each taluk, clusters of households in rural areas

and urban areas were selected. Each cluster consisted of 16 houses

(estimated based on the number of households to be covered by four field

workers in a day) both in urban and rural areas.

Further, within the rural areas, all villages in the

selected taluk were in the sampling frame. In each village, each cluster

consisted of 16 households. The number of clusters to be surveyed to

meet the required sample was arrived at.

In the case of urban areas, one town was selected

using a simple random sampling technique from the total number of towns

in the taluk. Like rural areas, 16 households made up one cluster. The

required number of clusters were selected from a randomly chosen

locality in the town.

The inclusion criterion was to have all six months to

<18-year permanent resident children, and visiting children living in

that area for a minimum duration of previous six months. Additionally,

information pertaining to deaths in the above age group due to

unintentional injuries was sought from the government sources. Birth

injuries or injuries consequent to intra-natal complications, and

disabilities due to other conditions were excluded.

After clearance from the institutional ethics

committee (IEC), permissions were obtained from the district and taluk

administrative authorities at all sites, the zilla panchayat CEO, and

the Child Development Project Officer for accessing information of

village panchayats and community health workers.

Data collection: Each site recruited four field

workers (medico-social workers) who underwent standardized training of 5

days, through a workshop conducted at each site. The workshop oriented

the field investigators to undertake an initial pilot study about child

injuries, the tool, rapport building in the community, data collection

procedures and hands-on instructions on using the electronic handheld

device.

Subsequently, field investigators prepared a spot map

of each selected village (rural area) or locality (urban area) and

numbered the houses serially. After explaining the study’s purpose in

the local language, informed written consent was obtained from the

respondent (parent/primary caregiver). Verbal assent was taken from

children more than or equal to 7 years of age. In addition to

interviewing the adult, children 7 years and above were also interviewed

to substantiate parents’ information. A history of previous three months

was used to collect information relating to all injuries whereas

information about fatal injuries was collected for the previous 12

months and verified in the register maintained in the panchayat office.

At the end of every interview, the caregivers were verbally provided

education regarding injury prevention among children.

Tool employed for data collection: The World

Health Organization (WHO) child injury questionnaire adapted to the

Indian settings was used [4]. Definitions for types (road traffic

accidents, falls, burns, poisoning, drowning, animal-related injuries)

and severity of injuries (mild, moderate and severe) was adapted from

the WHO standard definitions [6]. Injuries other than these types were

categorized as miscellaneous. A cloud-based soft-ware was developed

through an external vendor and validated. Each center received four

handheld devices for the field workers and one for the supervisor.

Quality assurance of data was built into the software with features of

valid entries, skip logic and consistency checks.

A robust management information system and dashboard

was developed through which each site could visualize their respective

electronic data on the web and download a copy of their data. Data were

analyzed centrally based on the approved statistical analysis plan.

Quality assurance: An operation manual and a

training manual for field workers were prepared by the coordinating team

and shared with the participating sites to ensure uniformity. Online

monthly meetings were organized by the central and national coordinating

sites with other site investigators and field workers for centralized

monitoring and supportive guidance to ensure regular interaction and

quality of data collected. The coordinating center continuously

monitored data through the dashboard. A team from the coordinating

center and ICMR team visited each of the sites during data collection

for supportive supervision. The investigators in each site revisited 5%

of households randomly and collected information independently to check

data quality and discrepancies if any, were resolved.

Statistical analyses: Data from all sites

were analyzed by the coordinating team using Statistical Package for the

Social Sciences 16.0 (SPSS Inc.). Data were coded according to severity

of injuries. Minor injuries were excluded for subsequent estimates. The

association between factors such as prevalence rate with age, gender,

and other factors was tested for statistical significance by Chi-square

test or Fisher’s exact test. The difference in mean values between two

groups was tested for statistical significance by Student’s t-test.

Probability value <0.05 was considered as cutoff for statistical

significance. Prevalence rates (period prevalence for 3 months) with 95%

confidence intervals were estimated.

RESULTS

The overall prevalence (95% CI) of unintentional

childhood injuries, including minor and trivial was noted to be 14.5%

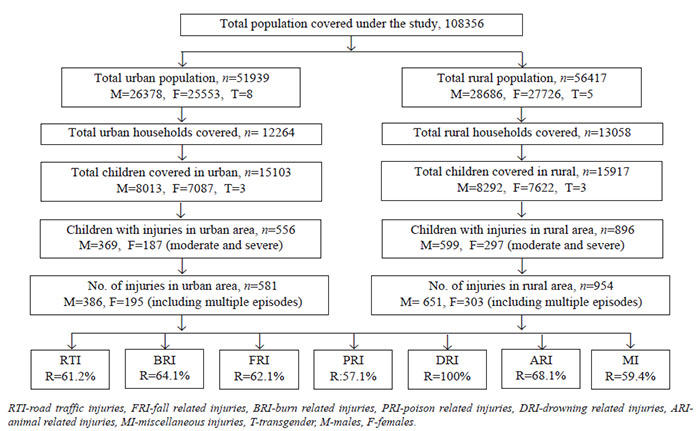

(14.1-14.9). Fig. 2 describes the samples selected and the

distribution of the types of injuries in all sites combined. However,

after excluding minor and trivial injuries, it was noted that 1452

children reported 1535 events of unintentional injuries. The prevalence

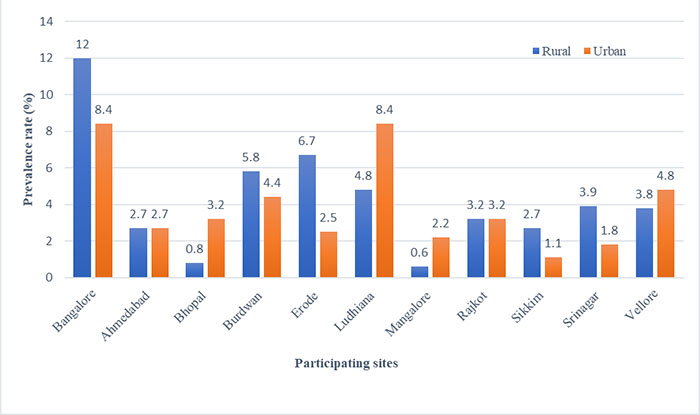

rate of injuries in various sites ranged from 0.6-12.0% (rural areas)

and 1.1-8.4% (urban areas) (Fig. 3). The prevalence was higher

among males as compared to females (5.9% vs 3.3%, P<0.001). The

differences in the prevalence rates between different age groups was

found to be statistically significant (P=0.01), with the lowest

prevalence rate among children below 1 year. The prevalence rate showed

a decreasing trend with increasing socioeconomic status. The difference

in prevalence based on the number of children in the family was minimal

(Table I).

Table I Socio/Demographic Characteristics and Prevalence of Injuries

|

No. of children |

No. with injury |

Prevalence |

|

n=31020 |

n=1452 |

(95% CI) |

| Age group |

|

|

|

| 6 mo - < 1 y |

768 |

2 |

0.3 (0.03-0.9) |

| 1-4 y |

6375 |

266 |

4.2 (3.7-4.7) |

| 5-9 y |

8682 |

449 |

5.2 (4.7-5.7) |

| 10-14 y |

9326 |

471 |

5.1 (4.6-5.5) |

| 15-<18 y |

5869 |

264 |

4.5 (3.9-5.1) |

| Gendera |

|

|

|

| Male |

16305 |

968 |

5.9 (5.5-6.3) |

| Female |

14709 |

484 |

3.3 (3.0-3.6) |

| Area of residence |

|

|

|

| Urban |

15103 |

556 |

3.7 (3.3-4.0) |

| Rural |

15917 |

896 |

5.6 (5.2-6.0) |

| Socioeconomic status |

|

|

|

| Lower |

3879 |

194 |

5.0 (4.3-5.7) |

| Lower middle and Upper lower |

24323 |

1190 |

4.9 (4.8-5.5) |

| Upper middle and Upper |

2818 |

6 |

2.4 (0.8-4.5) |

| Number of children in the family |

|

|

|

| 1-2 |

21313 |

1009 |

4.7 (4.2-5.2) |

| >2 |

9597 |

443 |

4.6 (4.0-5.1) |

| Type of family |

|

|

|

| Nuclear |

19323 |

921 |

4.8 (4.4-5.1) |

| Joint |

6759 |

316 |

4.7 (4.2-5.2) |

| Three generation |

4938 |

215 |

4.3 (3.8-4.9) |

| a6 were transgenders and none of

them had injuries. Comparisons of prevalence rates between

different age group, gender, area of residence, socioeconomic

status, number of children in the family, and type of family

showed all P<0.001. |

|

|

Fig. 2 Study flow and injury types at all

participating sites (excluding mild/trivial injuries).

|

|

|

Fig. 3 Site-wise injury prevalence rate

(%) by rural and urban areas.

|

Among the different types of injuries, fall-related

injuries had the highest prevalence rate of 2.7% (95% CI: 2.5-2.9)

followed by road traffic accidents (RTA) (1%; 95% CI: 0.8-1.1). Drowning

related injuries were the least (Table II). As per the World

Health Organization severity grading, burn injuries (44.7%) followed by

fall injuries (30.8%) reported a large number of severe type of

injuries. A total of five fatal injuries were reported across the

different sites (Table III).

Table II Prevalence of Different Types of Injuries (N=31020)

| Type of injury |

Prevalence rate (95% CI) |

| Road traffic injuries, n=304 |

1.0 (0.8-1.1) |

| Falls, n=842 |

2.7 (2.5-2.9) |

| Burns, n=103 |

0.3 (0.2-0.4) |

| Poisoning, n=14 |

0.05 (0.02-0.08) |

| Drowning, n=3 |

0.01 (0-0.03) |

| Animal-related, n= 94 |

0.3 (0.2-0.4) |

| Miscellaneous, n=175 |

0.6 (0.4-0.7) |

Table III Severity of Different Types of Injuries (N=1535)

| Type of injury |

Fatal injury |

Severe injury |

Serious injury |

Major injury |

Moderate injury |

|

n=5 |

n=444 |

n=404 |

n=423 |

n=259 |

| RTI |

1 (0.3) |

76 (25.0) |

81 (26.6) |

95 (31.3) |

51 (16.8) |

| Falls |

1 (0.1) |

259 (30.8) |

224 (26.6) |

20 (19.4) |

151 (17.9) |

| Burns |

1 (0.9) |

46 (44.7) |

32 (31.1) |

20 (19.4) |

4 (3.9) |

| Poisoning |

1 (7.1) |

1 (7.1) |

3 (21.3) |

7 (50.0) |

2 (14.2) |

| Drowning |

0 |

0 |

2 (66.7) |

1 (33.3) |

0 |

| Animal-related |

0 |

15 (15.9) |

20 (21.3) |

39 (41.5) |

20 (21.3) |

| Miscellaneous |

1 (0.6) |

47 (26.9) |

42 (24.0) |

54 (30.9) |

31 (17.7) |

| Values in no. (% of row total).

RTI: road traffic injuries. Classification of injury severity as

per World Health Organization [6]. |

Male children from rural areas in the age group of

5-9 years were commonly involved. The commonest location of injury for

all categories was at home. Age was an important factor associated with

different types of injuries. While road traffic accidents, predominantly

involved rural 10-14 year-old males (61.2%), fall-related injuries were

common among the younger 5-9 year-old children resulting in considerable

impairment (74.8%). However, in case of burn injuries, infants and

toddlers had a higher proportion (45.6%) as compared to their older

counterparts.

More than 80% of respondents with different types of

moderate and higher grades of injuries sought care at private clinics

initially. Most of the respondents reached the facility within one hour

of the occurrence of major injuries. Although activities of daily living

were affected among 88% of children with major injuries, more than 77%

of the children returned to their usual level of activity in a short

time. Less than a quarter of the respondents reported borrowing money

for treatment related to injuries. Although a large proportion of

children with injuries had some disability, most of them were temporary.

Permanent disability was noted in 4.3% in road traffic accidents, 11.8%

in falls, 16.5% in burns, 14.3% in poisoning, 11.7% in animal-related

and 10.3% in miscellaneous injuries.

DISCUSSION

This study was undertaken to obtain the population

estimates of unintentional childhood injures and major factors

associated with them. The all-site prevalence of injury including minor

and trivial was noted to be 14.5%. As per the reports from several

studies done in various parts of India, the prevalence of injury ranges

from 11% to 64% [7-9]. This wide range of prevalence may be attributed

to the variation in the sources of data, definitions used, and selection

criteria for assessing the burden of injuries.

Five deaths due to injuries were reported in one year

of the study recall period (0.16 per 1000 children). According to the

Bangalore Injury Surveillance Program (BISP), the ratio of fatal to

nonfatal injury in children below 18 years was 1:27 and male to female

ratio 3:1 [3]. Lower mortality rate reported in the present study may be

attributed to the poor reporting systems as well as absence of

validation of mortality reports for children below 18 years of age. An

ontological analysis of national programs in India revealed lack of

structured reporting mechanisms for childhood mortality [10].

Occurrence of injury was high among male children

compared to female children (2:1). This could be attributed to the

cultural practice of boys playing more outdoors as compared to girls,

especially in the higher age-groups. Higher prevalence in males was

reported by other studies as well [7, 8]. However, a study done in

Agartala did not find any relation between gender and injury prevalence

[9]. The confounding effect of the socio-cultural factors related to

gender and different activities across various age groups is to be noted

while interpreting the relationship between gender and injuries among

children.

We observed that injuries were more common among

children aged 5-14 years compared to children less than 5 years and 15

years and above, which has also been reported by Peden, et al. [11].

Children younger than 5 years usually have close adult supervision and

children older than 15 are relatively less playful. The age group 5-14

years are associated with independent locomotion with lack of

appreciation of risk of getting injured. Similar results were reported

by two other studies [1,12].

Falls contributed to 55% of injuries and most of them

occurred in the domestic environment. WHO global disease burden report

suggests that in most countries, falls are the most common type of

childhood injury seen in emergency departments, accounting up to 52% of

assessments. In Asia, falls are responsible for 43% of all injuries in

children [13]. Other studies have also reported falls to be the most

common injury which occurs in the home environment [2,7,11,14].

In Bangalore in 2007, 26% of injury deaths were due

to road traffic injuries, 17% due to burns, 13% due to falls, 6% caused

by drowning, and poisoning accounted for 5%. RTAs accounted for 40% of

hospitalizations due to injury. Surveys show that road traffic injuries

are one of the five leading causes of disability among children [2,3].

Burns (6.7% of injuries) were commonly reported due

to electric shock or contact with hot liquids or steam. According to

WHO, fire-related burns are the 11th leading cause of death for children

between the ages of 1-9 years [15]. Children under the age of five years

are at the highest risk of hospitalization from burns [12]. In India,

cooking at floor level and wood fired stoves contribute significantly to

burn injuries. Among older children, carelessness is an important

contributor to burn injuries caused by fireworks [16].

Although this study reports only three cases of

drowning in 5-9-year male children, it remains a health hazard. Fatal

drowning is the 13th cause of death among children. Globally, rate of

death due to drowning is 7.2 per 100000 population among children and

the rate is 6 times higher in low- and middle-income countries compared

to higher income countries [17]. Water storage sumps and ponds require

special attention to make them safe for young children. Poisoning was

reported more in rural areas. Kerosene poisoning is the most common

accidental poisoning among children in India, especially in the age

group of 1-3 years. Most injuries occur due to careless storage and use

of pesticides, insect and mosquito killers, and naphthalene acids [18].

Animal-related injuries were also more common in rural areas and

three-quarters of them were due to dog bites or scratches. The BISP has

reported that 11% of injuries in children were due to animal bites

[3,19]. A large portion of the Indian population live in rural

communities, with likelihood of close contact with animals and hence a

proclivity for animal-related injuries.

Domestic factors like inadequate living conditions,

poor housing, no separate area for washing or cooking, use of smoke

forming fuels, absence of cooking plat-forms, lack of safe storage area,

absence of dedicated recreational area for children are key factors in

the causation of injuries. Inadequate lighting would promote the chances

of accidents at home. These factors are the major cause of falls, burns

and accidental poisonings at home [7].

More than 50% of the children in the present study

had cut injuries and lacerated wounds. In a study on unintentional

injuries in the developing countries [20], cuts/bites and open wounds

(23.9%) were the most common injuries. Bruise/superficial injury and

burns accounted for 15% of all injuries while fracture was responsible

for 19% of the injuries [7]. Another study reported that the most common

physical nature of injury was bruise/superficial injuries (39.3%) and

cut/bite or open wound injuries (35.3%) [12]. Abrasion and contusion

contributed to around 1/3rd of injuries in our study, in contrast to

another study done in Aligarh, which reported superficial injuries among

under-five children and cut injuries among children aged more than 6

years [12].

A longitudinal study using verbal autopsy is helpful

in collecting accurate information on fatal injuries. Logistic problems

led to inability to collect data from all houses in hilly terrains and

during winters and heavy rains. Clusters of 16 houses could not be found

in sparsely populated areas/ hilly terrains and hence there is a need to

develop newer approaches and smaller cluster size in such areas.

The findings of the study point to the facets that

will be needed to formulate a comprehensive child injury prevention

policy in the country. Implementation of the policy should be

underscored at the level of the school and household. Child-safe schools

with age-appropriate measures, a safe home environment and road safety

measures for children should be a three-pronged approach in minimizing

the number and the severity of child injuries. These measures must be

reinforced through adolescent education, by articulating specific

interventions to control risk taking behavior. Focused attention on

‘injury-safe’ rural environments will also curtail the burden of child

injuries.

Acknowledgement: Pankaj Gupta, ICMR, New Delhi.

Kaushal Swaroop S, Kavin Corporation, Bangalore.

Ethical clearance: Institutional Ethics

Committees; Ramaiah Medical College, Bangalore; MSRMC/EC/2018, dated

February 5, 2018; GCS Medical college, Hospital and Research Centre,

Ahmedabad; GCSMC/EC/TRIAL/APPROVE/2018/ 24, dated January 28, 2018;

AIIMS, Bhopal; IHEC-LOP/2018/EF0077, dated January 27, 2018; Vellalar

College for Women, Erode; IEC/VCW/HR/2017/001, dated March 20, 2017;

Kasturba Medical College, Mangalore; IECKMCMLR/03-17/42, dated March 15,

2017; PDU Medical College, Rajkot; PDUMCR/IEC/11097, dated June 16,

2017; SRM university, Sikkim; SRMUS/MS/IEC/2018-01, dated February 10,

2018; VCSG Government Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, Pauri

Garhwal; IEC/VCSGGMSI&R/2018/027, dated January 18, 2018; Christian

Medical College, Vellore; IRB/10648/OBS; April 19, 2017; DMC &

H-Ludhiana, Punjab; IRB/DMC & H XX/2017, and Burdwan Medical College,

West Bengal; IEC/BMCXX/2017.

Contributors: All authors approved the final

version of manuscript and are accountable for all aspects related to the

study.

Funding: Indian Council of Medical Research;

Competing interests: None stated.

Annexure

List of Co-Investigators

Co-investigators from Participating Sites

NS Murthy, Babitha Rajan, Chandrika Rao, Sunil Kumar

BM and Anjana George, Ramaiah Medical College, Bangalore, Karnataka;

Bhavik Rana, Venu Shah and Viral Dave, GCS Medical College,

Ahmedabad, Gujarat; Abhijit Pakhare and Girish Bhatt, AIIMS,

Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh; Prabha Srivastava, Rupali Pitamber Thakur,

Raston Mondal, Somnath Naskar and Sutapa Mandal, Burdwan Medical

College, Burdwan, West Bengal; S Ponne, Vellalar College

for Women, Erode, Tamil Nadu; Siddharth Bhargava, Dayanand

Medical College and Hospital, Ludhiana, Punjab; Bhaskaran

Unnikrishnan, Rekha Thapar, Prasanna Mithra and Ramesh Holla,

Kasturba Medical College (Manipal Academy of Higher Education),

Mangalore, Karnataka; Umed Patel and Vibha Gosaliya, PDU Medical

College, Rajkot, Gujarat; Bhawana Regmi, Ojaswani Dubey and

Praveen Rizal, SRM University, Sikkim; Arjit Kumar and

Janki Bartwal, VCSG Medical College, Srinagar, Garhwal;

Sam Marconi, Anuradha Rose, Jasmin Helan Prasad and Anuradha

Bose, CMC, Vellore, Tamil Nadu.

Co-Investigator ICMR Members

Anju Sinha, Sukanya Sarma and RS Sharma, ICMR, New

Delhi.

ICMR Task-Force subject experts

Devendra Mishra, MAMC, New Delhi; G Gururaj, NIMHANS,

Bangalore, Karnataka; Kiran Aggarwal, Hindu Rao Hospital, New

Delhi; Piyush Gupta, UCMS and GTB Hospital, Delhi; Rakesh

Lodha, AIIMS, New Delhi; YK Sarin, MAMC, New Delhi.

|

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN?

• Information on childhood injuries is

largely available from hospital-based studies, with limited

population-based data.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS?

• The all-site prevalence of injuries in

children aged <18 years was 14.5% (including minor and trivial

injuries).

• Fall-related injuries were most common (54.8%), and most

injuries occurred in the domestic environment.

|

REFERENCES

1. Dunbar G, Hill R, Lewis V. Children’s attentional

skills and road behavior. J Exp Psychol Appl. 2001;7:227-34.

2. National Crime Record Bureau. Accidental deaths

and suicides in India. 2018.

3. Gururaj G. Injury prevention and care: An

important public health agenda for health, survival and safety of

children. Indian J Pediatr. 2013;80:100-8.

4. World Health Organization. Guidelines for

Conducting Community Surveys on Injuries and Violence. World Health

Organization; 2004.

5. Census of India, 2011. Provisional Population

Totals. New Delhi: Office of the Registrar General and Census

Commissioner. 2011.

6. World Health Organization. International

statistical classification of diseases and related health problems:

Tabular list. World Health Organization; 2004.

7. Majori S, Bonizzato G, Signorelli D, et al.

Epidemiology and prevention of domestic injuries among children in the

Verona area (north-east Italy). Ann. 2002;14:495-502.

8. Mathur A, Mehra L, Diwan V, et al. Unintentional

child-hood injuries in urban and rural Ujjain, India: A comm-unity-based

survey. Children (Basel). 2018;5:23-32.

9. Tripura K, Das R, Datta SS, et al. Prevalence and

manage-ment of domestic injuries among under five children in a peri-urban

area of Agartala, Tripura. Health Agenda. 2015;3:41-5.

10. Nanda Kumar BS, Madhumitha M, Ramaprasad A, et

al. National healthcare programs and policies in India: An ontological

analysis. International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health.

2017;4:307-13.

11. Peden M, Kayede O, Ozanne-Smith J, et al. World

report on child injury prevention: World Health Organization; 2008-2018.

12. Zaidi SHN, Khan Z, Khalique N. Injury pattern in

children: A population-based study. Indian J Community Health.

2013;25:45-51.

13. Murray CJ, Lopez AD. The global burden of

disease: A comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from

diseases, injuries, and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020:

Summary. World Health Organization; 1996.

14. Parmeswaran GG, Kalaivani M, Gupta SK, et al.

Unintentional childhood injuries in urban Delhi: A community-based

study. Indian J Community Med. 2017;42:8-12.

15. Peden M, Oyegbite K, Ozanne-Smith J, et al. World

report on child injury prevention. World Health Organization; 2009.

16. Bagri N, Saha A, Chandelia S, et al. Fireworks

injuries in children: A prospective study during the festival of lights.

Emerg Med Australas. 2013;25:452-6.

17. Hyder AA, Sugerman DE, Puvanachandra P, et al.

Global childhood unintentional injury surveillance in four cities in

developing countries: A pilot study. Bull World Health Organ.

2009;87:345-52.

18. Pal S, Patra DK, Roy B, et al. Profile of

accidental poisoning in children: Studied at urban based tertiary care

centre. Saudi J Med Pharma Sci. 2019:1110-3.

19. Sudarshan MK, Narayana DHA. Appraisal of

surveillance of human rabies and animal bites in seven states of India.

Indian J Public Health. 2019;63:3-8.

20. Mutto M, Lawoko S, Nansamba C, et al.

Unintentional childhood injury patterns, odds, and outcomes in Kampala

City: An analysis of surveillance data from the National Pediatric

Emergency Unit. J Inj Violence Res. 2011;3:13-8.

|

|

|

|

|