he World Health Organization

(WHO) Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education (IPE) and

Collaborative Practice has defined IPE as "an approach where

students from two or more professions learn about, from and with each

other" [1]. Centre for Advancement of Interprofessional Education

recognizes IPE as "occasions when members or students of two or more

professions learn with, from and about each other to improve

collaboration and the quality of care and services" [2].

As is evident from the definition, IPE stresses the

need for collaborative learning among learners drawn from different

streams of health care profession viz. – medical profession, nursing,

dental, physiotherapy and pharmaceutical professions. It must be

differentiated from multiprofessional education which is defined as

"occasions when two or more professions learn side by side for whatever

reason", thus defying any chance of collaborative and interdependent

learning [3].

Building the Case for Interprofessional Education and

Practice

The case-study (Box 1) provides

a classic description about the range of problems faced by health care

professionals due to lack of interprofessional coordination and

collaboration which may compromise the quality and safety of patient

care. In this backdrop, we discuss the curricular need to invest in

inter-professional education (IPE) to address the collaborative failures

featured in this case. IPE is recommended as an alternative to address

the current maladies associated with education and working in silos. The

paper shall delineate the way an interprofessional approach can offer

healthcare professionals with the much-required competencies in

providing a team based collaborative care. Besides highlighting the

range of fundamental issues related to IPE and inter-professional

practice (IPP), the review also attempts to emphasize the need for

patient centeredness and collaborative leadership.

|

BOX 1 Case Study to Illustrated Need for

Interprofessional Coordinations

N was brought to a pediatrician at the age of 2

years. Parents were concerned about his poor health. He weighed 10

kg, often had chest infections, and seemed to be developmentally way

behind peers in the community. N was operated at birth for duodenal

atresia and parents were told that he has a genetic problem that has

no cure. The family was on a regular follow up with their surgeon at

a tertiary care teaching hospital, until one year of age. After that

they had visited local doctors as and when required. Examination

revealed the child to have Down syndrome and malnutrition (PEM Grade

II). His developmental age was 9-12 months. The child also had a

pathologic cardiac murmur.

The pediatrician discussed Down syndrome with the

parents with overt surprise that they had not consulted him earlier

for vaccinations, infections, or poor growth and development. She

was dismayed over the past consultations that overlooked the

pertinent needs of an infant with Down syndrome. Later,

investigations revealed hypothyroidism and a ventricular septal

defect. Suitable medical management was started. Further follow-up

to plan growth monitoring and initiation of vaccination was

discussed with the parents.

|

Introduction to Interprofessional Education and

Practice

IPE provides opportunities for learners from

different health professions to come together to learn "from", "with"

and "about" each other [1]. This may be a starting point of coordinated

care among physicians, nurses, pharmacists and healthcare workers to

enhance patient outcomes. It reinforces a team-based approach towards

collaborative care.

With improved technology and new diagnostic and

treatment options available, healthcare is becoming complex day-by-day.

With the dawn of corporate-health culture, team-based and collaborative

approach to health care is establishing itself as the norm rather than

the exception. Though a healthcare team is assumed to work as a cohesive

unit, it is not uncommon to see health team members blaming each other

for patients’ problems and unfavorable health outcomes. Although the

contemporary health care requires ability to work in a team – and the

team is expanding, yet we never teach the students how to work with

other members.

Lack of knowledge to work as and in a health care

team, over-the-board assumption of superiority of one’s profession, and

cultural and communication gaps may be some of the reasons for failure

to work as a team. It has been reported that failure to learn and work

as healthcare team is resulting in poor patient-related outcomes. More

than a decade ago, it was reported that 70% of adverse events in

patient-care were avoidable. Report stated that these adverse events

were due to ‘compartmentalized and fragmented’ type of approach of

patient care and this fragmentation of care was preventing advancement

of patient care and patient safety [4]. A coherent and collaborative

approach to learn and work is the need of the hour.

Why Interprofessional Education?

It is assumed that if members of different

professions learn with, from, and about one another, they will

collaborate and work better together to progress in their professional

field as well as they will render improved services to the patients

resulting in improved clinical outcomes and quality of care being

provided to the patients [5]. The fragmented way in which healthcare is

being provided to the patients, and the disconnect between different

professions engaged in patientcare are often cited as barriers in

providing best healthcare to the patients [6]. It is argued that IPE

will ultimately produce a work-force ready for collaborative practice

guided by local health needs while working with the local health

infrastructure [4]. In a sense, IPE and collaborative practice is

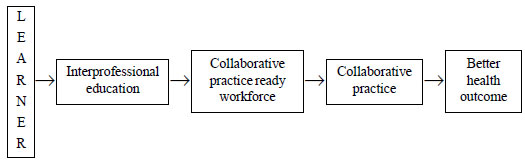

interdependent and the concept is detailed in Fig. 1 [7].

|

|

Fig. 1 Interdependence of

interprofessional education and collaborative practice leading

to better health outcomes.

|

A judiciously planned and systematically introduced

and conducted IPE program can enhance flexible, complementary,

patient-centered, and cost-effective coordination in interprofessional

teams while at the same time recognizing requirements of each profession

in the team and safeguarding profession-specific identity [8]. The

resultant collaborative practice and interpro-fessional care is proposed

to be a significant intervention to provide quality care; and an

efficient, cost-effective mode of healthcare [9-11].

Interdisciplinary integration has also been

documented as the tenth-level of integration in the 11-step ladder of

integrated teaching learning by Harden [12]. Interdisciplinary teaching

has been defined as ‘a study of a phenomenon that involves the use of

two or more academic disciplines simultaneously’ [13]. Evidently, as a

concept, IPE draws its basis from interdisciplinary integrated teaching,

thus bolstering the need of such an educational innovation in the arena

of medical education. Some of the benefits of IPE are detailed in

Box 2.

|

BOX 2 Benefits of Interprofessional

Education

Educational benefits

• Students will work in pragmatic conditions and

will encounter real world experiences

• Teaching faculty from different professions

will offer contributions for program development and implementation

bringing in wide range of experiences

• Will bolster mutual respect and trust among the

professionals involved

• Will give opportunities to develop competencies

to work as a team and develop leadership qualities

• Understanding of professional roles

• Enhanced communication and negotiation skills

and professionalism

• Students will learn about the modalities and

skills of other professional streams

Health policy benefits

• There will be improved workplace based

practices

• Improved patient/client-centered care and

quality enhancement

• Clinical and patient outcomes will be improved

• Staff confidence, self-esteem and morale will

be improved

• With collaborative and team based work culture,

patient safety will be improved

• Health care will be more cost-effective

• Access to health-care facilities will be

improved

• Emergency patient care and disaster management will be improved

|

Core Competencies in Interprofessional Education

The crux of an interprofessional curricular design

centers around the core interprofessional competencies viz.

values and ethics of interprofessional practice, agreed roles,

interprofessional communication, sound team work principles, and being

patient-centered [14].

IPE core competencies should be based upon some basic

principles, viz. they should be patient/family-centered;

community/population-oriented, relationship-focused and

process-oriented; should be aligned to teaching learning strategies and

assessment methods that are developmentally appropriate for the learner;

should be contextual and applicable across involved practice-settings;

should be applicable across all involved professions; must be stated in

language understood, common and meaningful across the professions; and

must be outcome driven [14].

Barr proposed three types of core competencies from

IPE perspective, viz. common, collaborative, and complementary

competencies [15]. Common compe-tencies are those which are expected to

be possessed by all health professionals. Complementary competencies

help other professions to improve the quality of patient care.

Collaborative competencies are the ones that each profession involved

needs to develop together with others, like other specialties within

their own profession, between different professions, with non-government

organizations and health volunteers, with patients, attendants and

families, within the community etc.

Values and ethics for interprofessional practice:

Ethical values hold the fort, not only for interprofessional working,

but for healthcare professional in general too; but with

interprofessional collaboration, holding high ethical virtues become

more important and become part of interprofessional professionalism.

Interprofessional Professionalism Collaborative has defined

interpro-fessional professionalism as ‘‘consistent demonstration of core

values evidenced by professionals working together, aspiring to and

wisely applying principles of altruism, excellence, caring, ethics,

respect, communi-cation, and accountability to achieve optimal health

and wellness in individuals and communities’’ [16]. Tavistock group

suggests ethical principles in interprofessional working as ‘ethical

principles for everybody in health care to hold in common, recognizing

the multidisci-plinary nature of health delivery systems’ [17]. An

expert panel has defined ten competency statements under values and

ethics for interprofessional practice core competency; some of them are

listed in Box 3 [14].

|

BOX 3 General Competency Statements for

Inter-Professional Core Competency

Value and ethics for interprofessional practice

• Interests of patients and populations are

placed at the center of interprofessional health care delivery while

maintaining privacy and confidentiality of the patients.

• Cultural diversity and individual differences

that characterize patients, populations, and the health care team

are respected.

• Work in cooperation with those who receive

care, those who provide care, and others who contribute to or

support the delivery of prevention and health services, in a

trusting relationship.

• Demonstrate high standards of ethical conduct

and quality of care in one’s contributions to team-based care and

manage ethical dilemmas specific to interprofessional patient/

population centered care situations while maintaining one’s own

professional competence.

Roles and responsibilities for collaborative

practice

• Communicate one’s roles and responsibilities

clearly to patients, families, and other professionals while

recognizing one’s professional limitations and is able to explain

the roles and responsibilities of other care providers and how the

team works together to provide care.

• Forge interdependent relationships with other

professions to improve care and advance learning, thus engaging in

continuous professional and interprofessional development to enhance

team performance

Interprofessional communication

• Choose effective communication tools and

techniques, including information systems and communication

technologies, to facilitate discussions and interactions that

enhance team function

• Organize and communicate information with

patients, families, and healthcare team members in a form that is

understandable, avoiding discipline-specific terminology when

possible

• Listen actively, and encourage ideas and

opinions of other team members while communicating consistently the

importance of teamwork in patient-centered and community-focused

care

Interprofessional team work and team-based practice

• Describe the process of team development and

the roles and practices of effective teams, while at the same time

engaging other health professionals - appropriate to the specific

care situation - in shared patient-centered problem-solving

• Apply leadership practices that support

collaborative practice and team effectiveness.

• Reflect on individual and team performance for

individual, as well as team, performance improvement with the use of

available evidence to inform effective teamwork and team-based

practices.

|

Roles and responsibilities for collaborative practice:

Learning and working as interprofessional requires understanding of the

role and duties of one as a member of the collaborative team, towards

team as well as to other professionals, towards patients and to

understand the roles and responsibilities of other members of the

interprofessional team. Nine competency statements for roles and

responsibilities for collaborative practice have been laid down (Box

3) [14].

Interprofessional communication practices:

Importance of effective communication lies in the way health

care professions communicate with patients, their attendants, other

members of health care team and authorities. Development of basic

communication skills is a common domain for health professions education

[18]. Moreover, effective interprofessional communication practices will

require the use of new communication technologies including informatics.

A committee of Institute of Medicine recommended that – ‘All

health professionals should be educated to deliver patient-centered care

as members of an interdisciplinary team, emphasizing evidence-based

practice, quality improvement approaches, and informatics’ [19].

Healthcare informatics not merely means information technology but

application of information technology systems to solve problems in

health care, research, and education, and the development of informatics

[20]. General competency statements for interprofessional communication

are summed-up in Box 3 [14].

Interprofessional teamwork and team-based practice:

Working in team is the motto of interprofessional education and

practice. Diverse competencies and cultural background of different

professionals working in a team can lead to multiple conflicts.

Resolving these conflicts and ability to continue to impart optimal

health care as a member of the interprofessional team is a competency to

be developed by an interprofessional health care provider. Open and

constructive approach to resolve these potential conflicts, team

leadership qualities and shared problem solving are some of the traits

that a good interprofessional health provider must imbibe. More detailed

general competency statements for interprofessional teamwork and

team-based practice are summed-up in Box 3 [14].

The list of interprofessional competencies is

considered comprehensive enough only when patient-centeredness and

collaborative leadership is considered along with these. Down syndrome

is one example of teaching-learning in an inter-professional scenario.

Table I depicts the errors in management and opportunities

provided by IPE and collaborative practice in managing this child with

Down syndrome.

|

Errors in management

|

Remedies as presented by

interprofessional education

|

|

Seemed as if the interests of the child were

put in the back-burner

No ethics were followed in the management of

the child’s condition

Child was never referred to pediatrician

before for confirmed diagnosis; No vaccination was provided to

the child; No cardiologist was consulted; in fact, child was

never referred to a specialist; Parents were never counseled

before, about providing care to the child; Services of

developmental pediatrician and psychologists were never asked

for.

There was total lack of cooperation among

different health care providers. No communication among required

health care providers was witnessed

|

Interests of the patient would have been at

the center in an IPE and collaborative practice set up

Ethical cooperation among other health

professionals - appropriate to the specific care situation would

have been possible

One professional would have been aware of his

competencies and limitations resulting in timely reference to

another specialist member of the team

Use of full scope of knowledge, skills, and

abilities of available health professionals would have been

possible resulting in better patient care

Communication among different members of team

would have been swift, enhancing team functioning

Overall, clinical outcomes would have been better

|

If one were to design an IPE curriculum for Down

syndrome, we would start by listing the learning objectives for Down

syndrome with respect to the level of the medical student viz

year 1,2 etc., followed by a written statement of the roles of teachers

of various specialties. For example, a geneticist, a pediatrician, a

pediatric surgeon, a pediatric cardiologist, a rehabilitation

specialist, etc. Each of the specialists must be part of a team that

collaboratively contributes to the inter-professional curriculum clearly

identifying the ‘must know’ and ‘nice to know’ areas for various level

of students. The curriculum should incorporate role-assignment, a

discussion on effective teaching learning strategies, and student

assessment. The inter-professional curriculum must necessarily include a

discussion on communication, ethics, and professionalism.

Teaching and Learning Approaches in IPE

Physician shadowing, team-based learning, and

community-based learning are some of the proposed strategies for

teaching learning in an IPE setting [6,21,22]. In shadowing, the student

learns by observing a physician in the real-life setting. Team-based

learning involves use of interactivity, roleplays, problem based

learning etc. which helps the learner learn the importance and attitudes

of being part of an interprofessional team [23-25]. Community-based

learning strategy, proposed in 1902, revolves around experiential

learning in the community [26]. Being situated in the real-life scenario

of the community, this strategy empowers the students to be better

adjusted in an interprofessional practice [27].

For the illustrative example in this article, Down

syndrome – students can experience observational learning in the

clinical setting of management of a child along with a physician and

surgeon and team based case discussion about how multidisciplinary care

of a child with Down syndrome can be organized and how the child should

be followed up with various specialists to not miss care of vital

issues, can be organized. Family study of how the family of a child with

Down syndrome copes with interprofessional referrals, their reactions

and attitudes to advices given, antenatal/genetic advice received,

access to rehabilitation services is an example of community based

learning strategy.

In addition, we need to acknowledge the role of

informal learning opportunities as an approach in IPE. It is an

unplanned offshoot of a planned interprofessional initiative. There are

instances when learners meet and discuss aspects of their formal

education allowing them to exchange ideas about their professions and

acquire direction from their peers and colleagues. Such informal

learning activities can be explicitly built into an interprofessional

program. For example, it can be used to provide opportunities during

breaks to informally discuss and share educational experiences. Studies

show that learners used bars and cafes to casually discuss and reflect

upon their interprofessional experience. These students have opined the

utility of this type of learning as valuable [28].

No single method is complete to deliver IPE.

Including learning experiences from different sources through varied

methods is also important to keep students interested and engaged.

Whichever methods are selected they should be experiential, interactive,

reflective and patient centered thus providing learning opportunities to

evaluate and compare roles, responsibilities, needs, ethics and

attitudes of practice, knowledge and skills of different professions

involved, leading to effective relationship building between the

professionals involved.

Assessment

IPE is a new concept and measuring competencies for

IPE and collaborative practice is a complex phenomenon [29]. Moreover,

the tools to assess collaborative competencies are also limited [30].

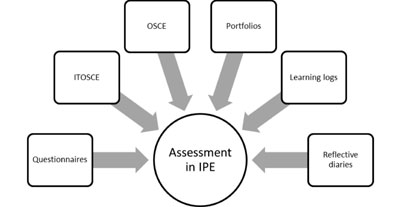

Assessment of IPE may be formative or summative. Reflective diaries,

learning logs, portfolios and Objective structured clinical examinations

(OSCEs) are some of the prevalent assessment methods used [8].

Reflective diaries and portfolios will give opportunities for

self-assessment and learning. A modified form of OSCE -

interprofessional team objective structured clinical examination

(ITOSCE) has been described by Symonds, et al. [31]. Whatever

program of assessment is chosen, the criteria and credits should be

reliable, valid, and consistent across professions. Some common

assessment methods for assessing learning in IPE

(Fig. 2) are:

|

|

Fig. 2 Assessment tools used

for assessing competencies for interprofessional education.

|

Reflective diaries: Reflective writing is by far

the most commonly used tool to assess IPE. It helps in self-assessment

as well as in learning too. It has been recommended that such reflective

writings should include – reflection before action, reflection in action

and reflection on action [32]. Reflective diaries help to assess if the

learners understand the roles, responsibilities and inter-personal

relationships in IPE. This tool has the inherent limitation that

learners may both underestimate or overestimate learning on

self-assessment. Reflective diaries are handy tools to assess knowledge,

skills, attitudes, and behaviors of learners for IPE and collaborative

practice.

Interprofessional team objective structured clinical

examination: As IPE involves team-work, it has been proposed that

team-assessment should be part of any assessment system for IPE.

However, the expectation that all will enter the team-environment with

same level of competency may hamper team-assessment. ITOSCE is a

formative assessment tool for assessing team-collaboration and

team-work. Learners, while working in team for ITOSCE, will move through

all five stages of Tuckman of group dynamics also and as such will take

time to learn and perform as a team. Though ITOSCE has been documented

to be logistically demanding, its educational impact is well established

[31].

Questionnaire: Standardized

questionnaires and checklists have been structured for assessing

attitudes and perceptions of learners about IPE, and can be good tools

for IPE program evaluation. Readiness for Interprofessional Learning

Scale (RIPLS) is the standardized tool most frequently used in IPE [33].

Other such questionnaire-based tools include - the Interdisciplinary

Education Perception Scale [34], the Interprofessional Attitudes

Questionnaire [35], and the Attitudes to Health Professionals

Questionnaire [36]. As stated, questionnaire-based tools can assess only

attitudes and perceptions of learners about IPE, and are not good

indicator of learning.

Assessment of learning based on IPE is an

interprofessional exercise too. It should be aligned with the learning

objectives for the area of concern. Various conventionally used tools of

assessment for different domains viz. application based multiple

choice questions, short answer questions, simulated patients, directly

observed procedural skills etc can be used to assess the

interprofessional learning.

Challenges in Adopting Interprofessional Education

Following are some of the challenges that

implementation of IPE faces in the current medical education scenario in

India.

Faculty development concerns: Content and tools

for training learning in IPE are different from usual health

professional education contents. So, faculty training and development in

IPE will be the first challenge in implementing IPE in health

institutes. Faculty needs to sensitize and train in various aspects of

IPE before taking-up the implementation part.

Development of curricula for IPE: Designing

common curricula for IPE for all professions involved, after considering

competency levels and expectations of all professions is next big

challenge. Curriculum development itself will involve collaboration of

different professional experts. Moreover, the curricula will vary from

institute to institute, from one encounter to other, depending upon the

type of professions involved and thus must be suitably amended and

adopted for every IPE team separately.

Logistic issues: Designing a common schedule and

adjust the timings to bring all learners together across many

professions will be logistically challenging. Similarly, it will be

problematic to bring all faculty/professionals required for teaching,

together at one common time. Moreover, all health profession institutes

may not have learners from different professions so as to make

collaborative-learning possible. This challenging situation can be

overcome by roping-in nearby located institutes imparting training in

other professions and with cooperation among administrative of these

institutes.

Assessment issues: Assessment in IPE is still in

its infancy, as stated above. There is urgent need to develop suitable

instruments to assess interprofessional-competencies so as to boost the

idea of competency-based interprofessional education.

Convincing learners: Convincing the learners –

the major stakeholders – for undergoing training in IPE will be a big

challenge. They need to be shown applicability and utilization of such

training. For this, collaborative practice in health care needs to be

made mandatory. Learners need to be ensured that there are enough

avenues for their placement after such training.

Lack of regulatory support: There are hardly any

regulations pertaining to IPE. Accreditation of IPE by accrediting

bodies across different professions is unheard-of. Bringing these

regulatory bodies on board and having common regulations across all

health professions involved in IPE is going to be the biggest challenge.

Policy decision at the national level can only change the perspectives.

In a nutshell, major barriers for IPE in the Indian

context are likely to be more systemic involving curricular and

accreditation issues. Handling of methodological barriers in terms of

faculty development, student diversity, communication issues and lack of

leadership can be challenging too. Behavioral barriers that relate to

stereotypes, mindset and resistance to change also need to be addressed.

Conclusion

The main utility of IPE is to produce

health-workforce ready to work in collaborative practice and thus

contributing to better health outcomes, thus improving both patients’

and health professionals’ satisfaction. Though being a relative

innovation, challenges are plenty, but with collaboration at different

levels and with right mind-set and approach these challenges can be

overcome easily. IPE is the next big thing, and for the better clinical

outcomes, for better health facilities and for better learners’ training

it should be adopted in the regular curricula urgently.

1. World Health Organization (WHO). Framework for

action on interprofessional education & collaborative practice. Geneva:

World Health Organization; 2010. Available from:

http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/70185/1/

WHO_HRH_HPN_10.3_eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed January 10, 2017.

2. CAIPE. 2002. What is CAIPE [homepage on internet].

Available from: https://www.caipe.org/. Accessed January 10,

2017.

3. Barr H. Interprofessional education: Today,

yesterday and tomorrow. Available from:

http://www.unmc.edu/bhecn/_documents/ipe-today-yesterday-tmmw-barr.pdf.

Accessed January 10, 2017.

4. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To Err is

Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academy

Press; 2000.

5. Reeves S, Fletcher S, Barr H, Birch I, Boet S,

Davies N, et al. A BEME systematic review of the effects of

interprofessional education: BEME Guide No. 39. Med Teach.

2016;38:656-68.

6. Nelson S, White CF, Hodges BD, Tassone M.

Interprofessional team training at the prelicensure level: a review of

the literature. Acad Med. 2017;92:709-16.

7. D’Amour D, Oandasan L. Interprofessionality as the

field of interprofessional practice and interprofessional education: an

emerging concept. J Interprof Care. 2005;19:8-20.

8. Barr H, Gray R, Helme M, Low H, Reeves S. In:

Interprofessional Education Guidelines 2016. London: Centre for

Advancement of Interprofessional Education; 2016. p. 5. Available from:

https://www.caipe.org/resources/publications/barr-h-grayr-helmem-low-h-reeves-2016-interprofessional-education-guidelines.

Accessed January 12, 2017.

9. Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, Cohen J, Crisp N,

Evans T, et al. Health professionals for a new century:

Transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent

world. Lancet. 2010;376:1923-58.

10. Baker DP, Gustafson S, Beaubien J. Medical

Teamwork and Patient Safety: The Evidence-Based Relation. Rockville, MD:

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2004. Available from:

https://archive.ahrq.gov/research/findings/final-reports/medteam/medteamwork.pdf.

Accessed January 10, 2017.

11. Nelson S, Turnbull J. Optimizing Scopes of

Practice: New Models for a New Health Care System: Report of the Expert

Panel Appointed by the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences. Ottawa,

Ontario, Canada: Canadian Academy of Health Sciences; 2014. Available

from:

http://www.cahs-acss.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Optimizing-Scopes-of-Practice_REPORT-English.pdf.

Accessed January 12, 2017.

12. Harden RM. The integration ladder: a tool for

curriculum planning and evaluation. Med Edu. 2000;34:551-7.

13. Jarvis P. In An International Dictionary of Adult

and Continuing Education. 2nd ed. London and New York: Routledge; 1990.

14. Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert

Panel. Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice:

Report of an expert panel. Washington, DC.: Interprofessional Education

Collaborative; 2011. Available from:

https://www.aamc.org/download/186750/data/core_competencies.pdf.

Accessed January 10, 2017.

15. Barr H. Competent to collaborate: Towards a

competency-based model for interprofessional education. J Interprof

Care. 1998;12:181-7.

16. Interprofessional Professionalism Collaborative.

Definition of Interprofessional Professionalism. Available from:

http://www.interprofessionalprofessionalism.org/index.html. Accessed

January 10, 2017.

17. Berwick D, Davidoff, F, Hiatt H, Smith R.

Refining and implementing the Tavistock principles for everybody in

health care. BMJ. 2001;323:616-20.

18. Association of American Medical Colleges. Report

III: Contemporary issues in medicine - Communication in medicine.

Medical School Objectives Project. Washington, DC; 1999. Available from:

https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/Contemporary%20Issues%20In%20Med%

20Commun%20in%20Medicine%20Report%20III%20. pdf. Accessed January

10, 2017.

19. Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality

Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC:

National Academy Press; 2001. Available from:

https://www.nap.edu/html/quality_chasm/reportbrief.pdf. Accessed

January 12, 2017.

20. Masys DR, Brennan PF, Ozbolt JG, Corn M,

Shortliffe EH. Are medical informatics and nursing informatics distinct

disciplines? The 1999 ACMI debate. J Am Med Information

Assoc. 2000;7:304-12.

21. Kusnoor AV, Stelljes LA. Interprofessional

learning through shadowing: Insights and lessons learned. Med

Teach. 2016;38:1278-84.

22. Hosny S, Kamel MH, El-Wazir Y, Gilbert J.

Integrating interprofessional education in community-based learning

activities: case study. Med Teach. 2013;Suppl 1:S68-73.

23. Kesten KS. Role-play using SBAR technique to

improve observed communication skills in senior nursing students. J Nurs

Educ. 2011;50:79-87.

24. Aebersold M, Tschannen D, Sculli G. Improving

nursing students’ communication skills using crew resource management

strategies. J Nurs Educ. 2013;52:125-30.

25. Garbee DD, Paige JT, Bonanno LS, Rusnak VV,

Barrier KM, Kozmenko LS, et al. Effectiveness of teamwork and

communication education using an interprofessional high-fidelity human

patient simulation critical care code. J Nurs Educ Pract. 2013;3:1-12.

26. Progressive education. Wikipedia. Available from:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Progressive_ education. Accessed

January 7, 2017.

27. Shumer R. Community-based learning: humanizing

education. J Adolescence. 1994;17:357-67.

28. Reeves S. Community-based interprofessional

education for medical, nursing and dental students. Health Soc Care

Commun. 2000;8:269-76.

29. Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional

Education (CAIPE). Principles of Interprofessional Education. London,

United Kingdom: CAIPE: 2001.

30. Morison S, Stewart M. Developing

interprofessional assessment. Learn Health Social Care. 2005;4:192-202.

31. Symonds I, Cullen L, Fraser D. Evaluation of a

formative interprofessional team objective structured clinical

examination (ITOSCE): A method of shared learning in maternity

education. Med Teach. 2003;25:38-41.

32. Simmons B, Wagner S. Assessment of continuing

interprofessional education: Lessons learned. J Contin Educ Health Prof.

2009;29:168-71.

33. Parsell G, Bligh J. The development of a

questionnaire to assess the readiness for health care students for

interprofessional learning (RIPLS). Med Educ. 1999;33:95-100.

34. Slack MK, Coyle RA, Draugalis JR. An evaluation

of instruments used to assess the impact of interdisciplinary training.

Issues in Interdisciplinary Care. 2001;3:59-67.

35. Carpenter J. Doctors and nurses: Stereotypes and

stereotype change in interprofessional education. J Interprof Care.

1995;9:151-61.

36. Lindqvist S, Duncan A, Shepstone L, Watts F, Pearce S.

Development of the ‘Attitudes to Health Professionals Questionnaire’

(AHPQ): A measure to assess inter-professional attitudes. J Interprof

Care. 2005;19:269-79.