|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2018;55:1066-1074 |

|

Indian Academy of

Pediatrics (IAP) Advisory Committee on Vaccines and Immunization

Practices (ACVIP) Recommended Immunization Schedule (2018-19)

and Update on Immunization for Children Aged 0 Through 18 Years

|

|

S Balasubramanian, Abhay Shah, Harish K Pemde, Pallab

Chatterjee, S Shivananda, Vijay Kumar Guduru, Santosh Soans, Digant

Shastri and Remesh Kumar

From Advisory Committee on Vaccines and Immunization

Practices (ACVIP), Indian Academy of Pediatrics, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Harish K Pemde, Director

Professor, Department of Pediatrics, Lady Hardinge Medical College,

Kalawati Saran Childern’s Hospital, New Delhi, India.

Email: [email protected]

|

|

Justification: There is a need

to revise/review recommendations regarding existing vaccines in view of

current developments in vaccinology. Process: Advisory Committee

on Vaccines and Immunization Practices (ACVIP) of Indian Academy of

Pediatrics (IAP) reviewed the new evidence, had two meetings, and

representatives of few vaccine manufacturers also presented their data.

The recommendations were finalized unanimously. Objectives: To

revise and review the IAP recommendations for 2018-19 and issue

recommendations on existing and certain new vaccines. Recommendations.

The major changes in the IAP 2018-19 Immunization Timetable include

administration of hepatitis B vaccine within 24 hours of age, acceptance

of four doses of hepatitis B vaccine if a combination pentavalent or

hexavalent vaccine is used, administration of DTwP or DTaP in the

primary series, and complete replacement of oral polio vaccine (OPV) by

injectable polio vaccine (IPV) as early as possible. In case IPV is not

available or feasible, the child should be offered three doses of

bivalent OPV. In such cases, the child should be advised to receive two

fractional doses of IPV at a Government facility at 6 and 14 weeks or at

least one dose of intramuscular IPV, either standalone or as a

combination, at 14 weeks. The first dose of monovalent Rotavirus vaccine

(RV1) can be administered at 6 weeks and the second at 10 weeks of age

in a two-dose schedule. Any of the available rotavirus vaccine may be

administered. Inactivated influenza vaccine (either trivalent or

quadrivalent) is recommended annually to all children between 6 months

to 5 years of age. Measles-containing vaccine (MMR/MR) should be

administered after 9 months of age. Additional dose of MR vaccine may be

administered during MR campaign for children 9 months to 15 years,

irrespective of previous vaccination status. Single dose of Typhoid

conjugate vaccine (TCV) is recommended from the age of 6 months and

beyond, and can be administered with MMR vaccine if administered at 9

months. Four-dose schedule of anti-rabies vaccine for Post Exposure

Prophylaxis as recommended by World Health Organization in 2018, is

endorsed, and monoclonal rabies antibody can be administered as an

alternative to Rabies immunoglobulin for post-exposure prophylaxis.

Keywords: Guidelines, Immunity, Infections,

Prevention, Vaccination.

|

|

T

he Indian Academy of Pediatrics (IAP) Advisory

Committee on Vaccines and Immunization Practices (ACVIP) has recently

reviewed and updated the recommended immunization schedule for children

aged 0 through 18 years based on recent evidence for the vaccines

licensed in India. The process of preparing the new recommendations

consisted of review of data and literature, consultative meetings twice

(4th and 5th August 2018 at Mangalore, and 22nd and 23rd September 2018

at Chennai), taking the opinion of various National Experts and arriving

at a consensus and drafting the recommendations while taking into

consideration the existing National immunization schedule and policies

of the government. All decisions were taken unanimously and voting was

not required for any issue. The recommendations in brief along with

supporting evidence from relevant literature are presented in this

article. The detailed information will be presented later in IAP

Guidebook on Immunization. While using these guidelines, pediatricians

are free to use their discretion in a particular situation within the

suggested framework.

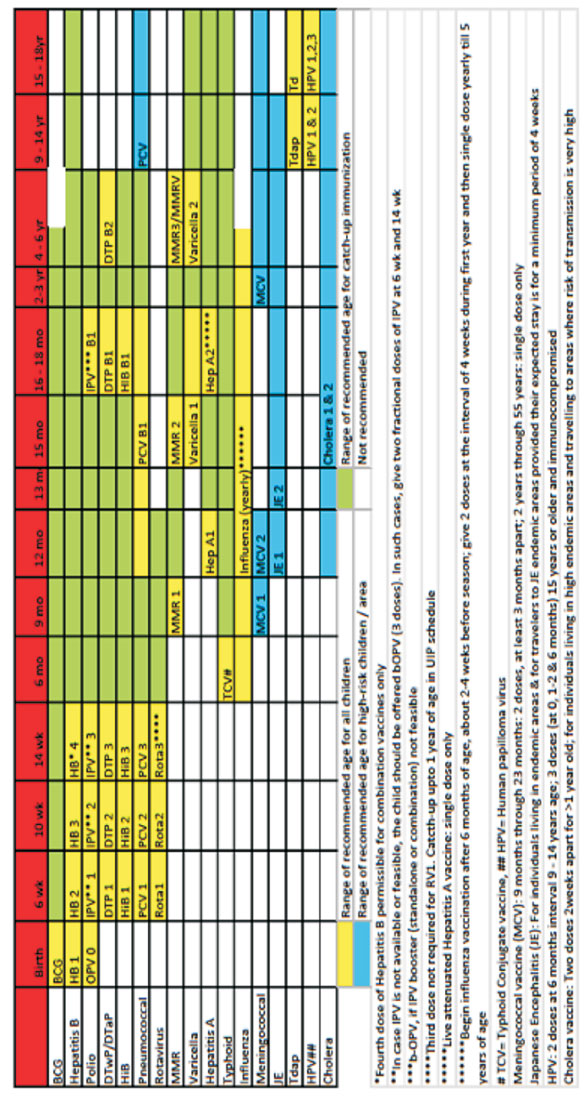

The current IAP ACVIP recommendations for the 2018-19

IAP Immunization Timetable are presented in Table I and

Fig. 1, and this also include some alterations from the

earlier recommended schedule [1].

TABLE I Key Updates and Major Changes in Recommendations for IAP Immunization Timetable, 2018-2019

|

Hepatitis B vaccine

• One dose of hepatitis B vaccine within 24 hours of birth.

• In case of use of a combination vaccines a total of four doses

of hepatitis B vaccine are justified.

DTwP, DTaP and combination vaccines

• DTwP or DTaP can be offered in primary series.

Polio vaccines

• Ideally IPV should replace OPV as early as possible.

• Three doses of intramuscular IPV in primary series is the best

option.

• Two doses of intramuscular IPV instead of three for primary

series if started at 8 weeks, with an interval of 8 weeks

between two doses is an alternative.

• In case IPV is not available or feasible, the child

should be offered three doses of bOPV. In such cases, the child

should be referred for two fractional doses of IPV at a Government

facility at 6 and 14 weeks or at least one dose of

intramuscular IPV, either standalone or as a combination vaccine,

at 14 weeks of age.

Rotavirus vaccine

• In case of Rotavirus vaccine, RV1 can be used in 6, 10 weeks

schedule.

Influenza vaccine

• Inactivated influenza vaccine (either trivalent or

quadrivalent) is recommended routinely to all children below 5

years of age starting from 6 months of age annually (2-4 weeks

before influenza season).

Measles-containing vaccines

• Measles-containing vaccine (MMR/MR) should be administered

after 9 months of age.

• MR vaccine as part of the national campaign is to be

administered irrespective of previous vaccination.

Typhoid vaccines

• Single dose of any of Typhoid conjugate vaccine (TCV 25 mg) is

recommended from 6 months onwards and can be

administered with MMR also.

• Booster dose of Typhoid conjugate vaccine not recommended in

subsequent years.

Rabies vaccines

• ACVIP IAP endorses administration of a 4-dose schedule of

Rabies vaccine recommended by WHO 2018 for Post-

exposure prophylaxis.

• ACVIP also endorses administration of Rabies monoclonal

antibody as an alternative to Rabies immunoglobulin for

category-III bites.

|

|

ACVIP: Advisory Committee on Vaccines and Immunization

Practices; IAP: Indian Academy of Pediatrics; IPV: Injectable

polio vaccine; OPV: Oral polio vaccine; bOPV: bivalent oral

polio vaccine; MR: Measles-Rubella vaccine; MMR:

Measles-Mumps-Rubella vaccine. |

|

|

Fig. 1 IAP-ACVIP Recommended

immunization schedule for children aged 0-18 years (2018-19).

|

Hepatitis B Vaccine

The burden of chronic hepatitis B virus infection is

substantial as the coverage of the birth-dose (estimated as 39%

globally) is still low. World Health Organization (WHO) Position paper

2017 states that hepatitis B vaccine (HBV) should be administered as a

birth dose, preferably within 24 hours (timely birth dose) [2]. This

dose may only be delayed if the mother is known to be hepatitis-B

surface antigen (HBsAg) negative at the time of delivery. When the HBsAg

report of the mother is not known or reported incorrectly, or in case of

infants born to HBsAg positive mothers, this dose becomes a very

important safety net [3].

Four doses of hepatitis B vaccine may be administered

for programmatic reasons (e.g., 3 doses of hepatitis B-containing

combination vaccine or monovalent HBV after a single monovalent dose at

birth [2].

Diptheria, Tetanus and Pertussis Vaccines (DTwP and

DTaP)

Long-term efficacy over 10 years has been observed to

be superior with whole cell pertussis vaccine (wP) [4]. Recent outbreaks

of pertussis in various developed countries have sparked a debate on the

effectiveness of acellular pertussis (aP) vaccines. However, none of

these countries are planning to revert back to whole-cell pertussis

vaccines as that can result in an increase in the prevalence of the

disease due to poor acceptance of a vaccine that is much more

reactogenic [5]. Though the reasons for this resurgence are complex and

vary from place to place, the lesser duration of protection and

decreased impact on transmission of the disease by acellular pertussis

vaccines appears to be crucial [6]. Waning of immunity has been reported

with whole cell and acellular vaccines over a period of time. Current

evidence suggests that the efficacy of both aP and wP vaccines in

preventing pertussis in the first year is equivalent. After the first

year, the immunity wanes more rapidly with the aP vaccines and the

impact on transmission by aP vaccines is also inferior to wP vaccines

[7-9]. WHO clearly mentions that countries currently using the wP

vaccine in their national programs should continue the same for the

primary series [10,11], while those using the aP vaccine should continue

the same and consider additional boosters and strategies like

immunization of mothers in case of pertussis resurgence [10]. The

duration of protection for both the aP and wP vaccines after the three

primary doses and a booster dose at least after a year varies from 6-12

years [11]. A German study reported acellular pertussis vaccine being

quite efficacious (88.7%) (95% CI, 76.6% to 94.6%) [12].

Number of Components

In a couple of systematic reviews, it was concluded

that multi-component acellular pertussis vaccines are more efficacious

than the single- or two-component vaccines [13,14]. However,

effectiveness studies of long-term usage of two-component acellular

pertussis vaccines in Sweden [15] and Japan [16], and the mono-component

vaccine in Denmark showed high effectiveness in prevention of pertussis.

Thus the higher efficacy for the multi-component vaccine as demonstrated

in the trials should be cautiously interpreted, and at present the

evidence is insufficient to conclude categorically that the

effectiveness of the aP vaccines is related to the number of components

alone [10].

IAP ACVIP Recommendation on Pertussis-containing

Vaccines

The primary series should be completed with three

doses of either wP or aP vaccines, irrespective of the number of

components. wP vaccine is definitely superior to aP vaccine in terms of

immunogenicity and duration of protection but more reactogenic. In view

of parental anxiety and concerns for its reactogenicity, aP vaccine can

also be administered even in the primary series. The primary aim is to

increase the vaccination coverage with either of the vaccines.

Polio Vaccines

The elimination of circulating wild poliovirus from

our country and the decline worldwide in the number of cases is the

proof of efficacy of Oral polio vaccine (OPV). At the beginning of 2013,

126 countries using OPV exclusively, decided to introduce Injectable

polio vaccine (IPV), at least one dose, in their National Immunization

Schedule. This was part of WHO’s Endgame Plan to withdraw type-2 polio

virus and prepare for ‘the switch’ from trivalent OPV (tOPV) to bivalent

OPV (bOPV) in April 2016 [17,18]. However, IPV introduction in these

countries has increased the global IPV demand, to over 200 million in

2016 from 80 million in 2013 [17,18]. The attempt to meet the global

requirements for IPV by rapidly increasing the IPV production has led to

multiple challenges, resulting in a shortage worldwide. Intradermal IPV

administration with fractional doses of IPV (fIPV) (0.1 mL or one-fifth

of a full dose) offers potential cost reduction and allows immunization

of a larger number of persons with a given vaccine supply [19]. Two

fractional doses administered via the intradermal (ID) route

offer higher immunogenicity compared to one full intramuscular (IM) dose

of IPV [20-23]. As a result, a two-dose fIPV schedule has been strongly

recommended to countries that are endemic and the those with high risk

of importation of wild polio virus [24].

Private medical practitioners have irregular and

inadequate access to standalone IPV, and are thus compelled to

administer combination vaccines, and thus are not able to follow the

Indian government schedule, which consists of fIPV and standalone IPV.

It is not feasible for pediatricians in private settings to refer all

children to government facilities for the same. In addition, the recent

controversy of the contamination of OPV with type-2 Poliovirus has

resulted in the awareness of vaccine-derived paralytic poliomyelitis

(VDPP) amongst public. In this background, there is a need to recommend

a regimen containing IPV as combination vaccine in the private settings.

IAP ACVIP Recommendations

• Birth dose of OPV is a must.

• Extra doses of OPV on all Supplementary

immunization activities should continue.

• No child should leave the health facility

without polio immunization (IPV or OPV), if indicated by the

schedule.

• bOPV should be continued in place of IPV, only

if IPV is not feasible, with a minimum of 3 doses at 6,10,14 weeks

of age.

• Minimum age of administration of IPV is 6 weeks

with the best option being 3 doses of IM IPV in 6-10-14 weeks

schedule. This can be as a combination vaccine, in view of

non-availability of standalone IM IPV.

• Two doses of IM IPV, instead of 3 doses can be

administered provided the primary series is started at 8 weeks with

the minimum interval between them being 8 weeks.

• In case IPV is not available or feasible, the

child should be offered 3 doses of bOPV in a 6-10-14 weeks schedule.

In such cases, the child should be advised to receive two fractional

doses of IPV at a Government facility at 6 and 14 weeks of age or at

least one dose of IM IPV either standalone or as a part of

combination vaccine at 14 weeks.

Rotavirus Vaccines

A review of studies from 38 populations found that

all rotavirus gastroenteritis events (RVGE) occurred in 1%, 3%, 6%, 8%,

10%, 22% and 32% children by age 6, 9, 13, 15, 17, 26 and 32 weeks,

respectively. Mortality was mostly related to RVGE events occurring

before 32 weeks of age [25]. The highest risk of mortality was noted in

the children having earliest exposure to rotavirus, living in poor rural

households, and having lowest level of vaccine coverage [26]. It is

ideal if immunization schedule is completed early in developing

countries where natural infection might occur early [27].

Infants in developing countries may be at risk of

developing RVGE at an earlier age than those in developed countries.

They also tend to have a higher risk of mortality coupled with the risk

of lower vaccine coverage. No observational study has compared different

ages at first dose. A schedule of two doses at 10 and 14 weeks may

result in incomplete course of vaccination, especially in developing

countries because of restriction of upper age limit for rotavirus

vaccine administration. Such children would remain immunologically

susceptible to get rotavirus infection. Early administration of the

first dose of rotavirus vaccine as soon as possible after 6 weeks of age

has been recommended by WHO recently [27]. Administration of RV1 or RV5

vaccine at 6 weeks has also been recommended and approved even in

developed countries [28].

Two randomized controlled trials reported data on

severe rotavirus gastroenteritis with up to one year follow-up, and

directly compared children who received the first dose of RV1 at age 6

weeks vs 10 to 11 weeks. No statistically significant difference

in efficacy was found between these two schedules [29]. The South Africa

and Malawi RV1 trial [30] reported similar efficacy of vaccination

schedules beginning at 6 weeks or 10 to 11 weeks against severe RVGE

during the second year follow-up using only the Malawi cohort. Indirect

comparisons based on stratification of RV1 and RV5 trials using

different schedules showed no impact on mortality for different ages at

first dose.

Considering these factors, ACVIP recommends RV1 in a

schedule of 6 and 10 weeks. The recommendations for the schedule of

other vaccines remain the same.

Currently the following live oral rotavirus vaccines

are available in India: (i) Human monovalent live vaccine (RV1);

(ii) Human bovine pentavalent live vaccine (RV5); (iii)

Indian neonatal rotavirus live vaccine, 116 E; (iv) Bovine

Rotavirus Vaccine – Pentavalent (BRV-PV). BRV-PV is a recently

introduced pentavalent rotavirus vaccine that contains serotypes G1, G2,

G3, G4, and G9 obtained from Bovine (UK) X Human Rotavirus Reassortant

strains. It is a thermostable vaccine and can be stored below 24

0C till the duration of the shelf

life of 30 months. This vaccine remains stable for 36 months at

temperature below 25 0C

, for 18 months between 37 0C

and 40 0C

, and a short-term exposure at 55

0C

[31].

IAP ACVIP Recommendation on Rotavirus Vaccines

Any of the available rotavirus vaccines may be

routinely administered as per the manufacturer’s recommendations. All

the available vaccines have been demonstrated to be safe and

immunogenic.

• Minimum age: 6 weeks for all available brands

• Only two doses of RV-1 are recommended at 6 and

10 weeks

• If any dose in series was RV-5 or RV-116E or

vaccine product is unknown for any dose in the series, a total of

three doses of RV vaccine should be administered.

Recommendations on the age limit for the first dose

and the last dose (16 and 32 weeks) should continue in spite of

recommendation for increase in the age limit as per recent NIP

guidelines.

Typhoid Vaccine

Considering the continuation of significant burden of

typhoid fever, widespread prevalence of antibiotic-resistant strains of

S. typhi and availability of favorable evidence on the efficacy,

effectiveness, immunogenicity, safety, and cost-effectiveness of typhoid

vaccines, WHO recommends use of typhoid vaccines in national programs

for the control of typhoid fever [32,33]. Typhoid conjugate vaccine

(TCV) is preferred at all ages as it has improved immunological

properties, can be used in younger children, and is expected to provide

longer duration of protection. A meta-analysis summarized that typhoid

cases across the age groups; 14% to 29% in <5 years, 30% to 44% in 5-9

years and 28% to 52% in 10-14 years [34]. It has been observed that more

than one-fourth of all cases occur in children aged below 4 years, with

approximately 30% of cases in children aged below 2 years, and 10% in

children aged below 1 year [35]. Based on this, WHO has recommended TCV

for infants and children from 6 months of age as a 0.5 mL single dose

[36], and the same is endorsed by ACVIP.

Booster Doses/Revaccination

The need for revaccination with TCV is currently

unclear [36]. The protection with TCV may last for up to 5 years after

the administration of one dose, and natural boosting may occur in

endemic areas [37]. The evidence concerning the need for booster

vaccination is lacking currently. Until more data is generated or

available, the ACVIP recommends only a single dose of TCV from 6 months

onwards. If a child has received Typhoid polysachharide vaccine, it is

recommended to offer one dose of TCV at least 4 weeks following the

receipt of polysaccharide vaccine.

Currently, three products of TCV are licensed in

India. Two of them contain 25 µg of purified Vi PS of S. typhi,

and one of them containing 5 µg purified Vi PS of S. typhi. The

WHO position paper in 2018 has remarked that the body of evidence for

the 5 µg vaccine is very limited.

IAP ACVIP Recommendation on Typhoid Vaccines

Primary schedule

• A single dose of TCV 25 µg is recommended from

the age of 6 months onwards routinely.

• An interval of at least 4 weeks is not

mandatory between TCV and measles-containing vaccine when it is

offered at age of 9 months or beyond.

• For a child who has received only Typhoid

polysaccharide vaccine, a single dose of TCV is recommended at least

4 weeks following the receipt of polysaccharide vaccine. Routine

booster for TCV at 2 years is not recommended as of now.

Measles, Mumps and Rubella (MMR/MR) Vaccines

Standalone measles vaccine is now not available for

regular use. Measles-containing vaccine (MMR/MR) should be administered

after 9 months of age (270 days). MR (Measles-Rubella) vaccine is

currently not available in the private sector. Hence in view of

morbidity following mumps infection, it has been recommended that MMR is

administered instead of MR at 9 months, 15 months, and 4-6 years [38],

or as two doses at 12 to 15 months of age with the second dose between 4

to 6 years of age. [39]. Additional dose of MR vaccine during MR

campaign for children 9 months to 15 years, irrespective of previous

vaccination status is to be administered, keeping in mind the need to

support national programs.

Influenza Vaccine

A meta-analysis and systematic review evaluating

studies published between 1995 to 2010 estimated that children under 5

years of age had 90 million (95% CI 49-162 million) new influenza

episodes, 20 million (95% CI 13-32 million) cases of acute lower

respiratory infections (ALRI) where influenza was associated, and 1

million (95% CI 1-2 million) cases of severe ALRI (associated with

influenza). This resulted in 28,000-111,500 deaths attributed to

influenza, with 99% of them from developing countries [40]. Another

study estimated that globally 160,000-450,000 children below 5 years of

age die in hospitals each year due to all-cause ALRI [41].

A systematic literature review described that during

the peak rainy season, influenza accounted for 20-42% of monthly acute

medical illness hospitalizations in India [42]. This suggests that

influenza is a substantial contributor to severe respiratory illness and

hospitalization. The findings from the studies also show that influenza

circulation and influenza-associated hospitalization are major public

health concerns in India. There is poor uptake of the influenza vaccine

in India. IAP position paper on influenza in 2013 stated the while it

may not be practical to recommend routine influenza vaccination to

everyone in India, the vaccination for high-risk groups such as the

elderly, children below 5 years, medical practitioners and pregnant

women should be seriously considered [43]. Influenza incidence in

children below 5 years of age from developing countries is three times

higher than those from developed countries, with a 15-fold higher

case-fatality [41].

Health utilization surveys conducted in two rural

sites (Ballabgarh, Haryana and Vadu, Maharashtra) in 2010-2012 reported

adjusted all-age incidence rates of influenza-associated hospitalization

as 3.8-5.4 per 10,000 in Ballabgarh and 20.3-51.6 per 10,000 in Vadu

[44]. The age-specific influenza-associated hospitalization rates varied

from year to year. In 2010, these rates were highest among persons aged

<1 year, in 2011 among patients >59 years of age, and in 2012 in

children 1-4 years in Ballabhgarh. Whereas in Vadu, in 2010, these rates

were highest among persons aged 1-4 years, in 2011 in children <1 year,

and in 2012 in children 5-14 years. Influenza viruses were found

throughout the year and the peaks coincided with peaks in rain fall at

both the sites.

The Influenza Serotype-B is reported almost round the

year in India. A multi-site influenza study in India found that 27.8%

isolates were Influenza A (H1N1) virus, 29.8% were type A (H3N2), and

42.3% isolates were type B [45]. A global influenza study found that

during seasons, out of all influenza B isolates, Victoria and Yamagata

lineages predominated or co-circulated (>20% of total detections), and

this accounted for 64% and 36% of seasons respectively. The vaccine

virus mismatch was found in 25% of the seasons [46].

With the available data, there is enough reason to

believe that the magnitude of the problem is much higher in developing

countries (including India) vis-a-vis developed countries. India

lies within the northern hemisphere. Some parts of the country

experience a distinct tropical environment because of its location close

to the equator. These areas have a southern hemisphere seasonality with

almost round-the-year circulation of influenza viruses peaking during

monsoon. Northern parts of India experience another peak during winters

similar to northern hemisphere pattern. There is continuous influenza

activity across the nation, with seasonal peaks during monsoon and

winter, and an ever increasing number of influenza-like illnesses

affecting a large number of children who can transmit the disease to

their peers and adult counterparts.

In view of influenza activity round the year with

seasonal peaks, high morbidity and mortality in high-risk groups,

including children below 5 years, paucity of facilities for laboratory

diagnosis, high transmission rate, substantial socioeconomic burden,

limitations of oseltamivir, availability of moderately efficacious

vaccine, it would be justifiable to use Influenza vaccine routinely in

the high-risk group of children below age of 5 years.

Vaccine Strains

FDA recommended the following combinations for

2018-19 influenza vaccines.

• Trivalent vaccines-to have (i) an

A/Michigan/45/2015 (H1N1)pdm09-like virus, (ii) an

A/Singapore/INFIMH-16-0019/2016 (H3N2)-like virus; and (iii)

a B/Colorado/06/2017-like virus (Victoria lineage).

• Quadrivalent vaccines to contain the above

three, and a B/Phuket/3073/2013-like virus (Yamagata lineage) [47].

IAP ACVIP Recommendations

ACVIP recommends that quadrivalent/trivalent

inactivated influenza vaccine should be routinely offered annually to

all children between 6 months to 5 years of age. The latest available

influenza vaccine can be administered after 6 months of age, 2-4 weeks

prior to the influenza season: two doses at the interval of one month in

the first year, and one dose annually before the influenza season up to

5 years of age.

Rabies Vaccine

Recent data indicate that duration and number of

doses for post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)

regimens can be shortened. ACVIP endorses the new schedule suggested by

WHO in 2018 [48].

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (Pre-EP) is recommended in

the following two situations.

• Children exposed to pets in home.

• Children identified to have a higher risk of

being bitten by dogs.

WHO recommends a "1-site vaccine administration on

days 0 and 7 for intramuscular administration" [48].

For post-exposure prophylaxis, recently the WHO [48]

has recommended a new 4-dose schedule of either of the following: (i)

1-site intramuscular administration of vaccine on days 0, 3, 7 and

between day 14-28, or (ii) 2-sites intramuscular administration

on days 0 and 1-site on days 7, 21 (intramuscular).

Rabies Human Monoclonal Antibody (RHMAB)

Access to Rabies immunoglobulin (RIG) is limited

resulting in high rabies mortality. RHMAB is a completely human IgG1

monoclonal antibody that binds to the ectodomain of the G glycoprotein

produced by recombinant technology. It has been demonstrated to

neutralize 25 different isolates of wild-type or street isolates of

rabies virus. A recent study found that it is not inferior to Human

rabies immunoglobulin (HRIG) in producing rabies virus neutralizing

antibody in 200 subjects with WHO category-III suspected rabies

exposures. The study subjects received either RMHAB or HRIG (1:1 ratio)

in wounds, and intramuscularly wherever necessary, on day-0. All these

patients also received five doses of rabies vaccine intramuscularly on

0, 3, 7, 14 and 28 days [49].

This newly introduced monoclonal antibody has emerged

as a safe and potent alternative to rabies immunoglobulin. The WHO

position paper on Rabies in 2018 has also suggested encouragement of use

of this product, if available, instead of RIG. The comparative

advantages include easy availability, standardized production quality,

possibly greater effectiveness, no requirement of animals in its

production, and less adverse events.

In view of the irregular availability and high cost

of Rabies immunoglobin (RIG), ACVIP endorses the use of RHMAB as an

alternative to RIG – human or equine – along with rabies vaccines in all

category-III bites. RHMAB is licensed in India (as Rabisheild, Serum

Institute of India; 40 IU/mL) since 2017. The recommended dose is 3.33

IU/kg body weight, preferably at the time of the first vaccine dose.

However, this may also be administered up to the 7th day after the first

dose of vaccine is given. If the calculated dose is insufficient (to

infiltrate all the wounds), it should be diluted in sterile normal

saline to get a volume that is enough to be infiltrated around all the

wounds.

Funding: None. Indian Academy of Pediatrics

provided the consultative meetings’ expenses.

Competing interest: Representatives of a few

vaccine manufacturing companies also presented their data in the

consultative meetings. None stated for authors.

Annexure I IAP Advisory Committee on Vaccines

and Immunization Practices, 2018-19

Office-bearers: Santosh Soans

(Chairperson), Digant Shastri (Co-Chairperson), S Balasubramanian

(Convener); Members: Abhay Shah, G Vijaykumar, Harish K Pemde,

Pallab Chatterjee, S Shivananda

Rapporteur: Abhay Shah

Indian Academy of Pediatrics:

Santosh Soans (President), Digant Shastri (President-Elect), Anupam

Sachdeva (Immediate Past President), Vineet K Saxena, Arup Roy, Kedar S

Malwatkar, Harmesh Singh, D Gunasingh (Vice-Presidents), Remesh Kumar

(Secretary General), Upendra S Kinjawadekar (Treasurer), Dheeraj Shah

(Editor-in-Chief, Indian Pediatrics), NC Gowrishankar (Editor-in-Chief,

Indian Journal of Practical Pediatrics), Sangeeta Yadav, Sandeep B Kadam

(Joint Secretaries)

Writing committee: S Balasubramanian, Abhay

Shah, Harish K Pemde, Pallab Chatterjee, S Shivananda, Vijay Kumar

Guduru, Santosh Soans, Digant Shastri, Remesh Kumar

References

1. Vashishtha VM, Choudhury P, Kalra A, Bose A,

Thacker N, Yewale VN, et al. Indian Academy of Pediatrics (IAP)

recommended immunization schedule for children aged 0 through 18 years –

India, 2014 and updates on immunization. Indian Pediatr.

2014;51:785-800.

2. Hepatitis B vaccines: WHO position paper – No 27,

2017, World Health Organization. Weekly epidemiological record. No 27,

2017, 92, 369-392.

3. Elizabeth D. Barnett, Give first dose of HepB

vaccine within 24 hours of birth: American Academy of Pediatrics August

28, 2017. Available from:

http://www.aappublications.org/news/2017/08/28/HepB082817. Accessed

Nov 6, 2018.

4. Cherry JD. Pertussis and Immunizations: Facts,

Myths, and Misconceptions. Available from: http://aap-ca.org/pertussis-and-immunizations-facts-myths-and-misconceptions.

Accessed November 6, 2018.

5. Munoz FM. Safer pertussis vaccines for children:

Trading efficacy for safety. Pediatrics. 2018;142:e20181036.

6. Jackson DW, Rohani P. Perplexities of pertussis:

Recent global epidemiological trends and their potential causes.

Epidemiol Infect. 2013;16:1-13.

7. Winter K, Harriman K, Zipprich J, Schechter R,

Talarico J, Watt J, et al. California pertussis epidemic, 2010. J

Pediatr. 2012;161:1091-6.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Pertussis epidemic—Washington, 2012. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep.

2012;61:517-22.

9. Pertussis vaccines: WHO Position Paper – August

2015 No. 35. World Health Organization. Weekly Epidemiological Record.

2015;90:433-60.

10. World Health Organization. Pertussis Vaccine

Evidence to Recommendations (WHO). Available from:

http://www.who.int/immunization/position_papers/Pertussis

GradeTable3.pdf. Accessed November 6, 2018.

11. WHO Position paper on Pertusis Vaccine, 2005.

World Health Organization. Weekly Epidemiological Record. 2005;4:29-40.

12. Schmitt HJ, von König CH, Neiss A, Bogaerts H,

Bock HL, Schulte-Wissermann H, et al. Efficacy of acellular

pertussis vaccine in early childhood after household exposure. JAMA.

1996;275:37-41.

13. Jefferson T, Rudin M, DiPietrantonj C. Systematic

review of the effects of pertussis vaccines in children. Vaccine.

2003;21:2003-14.

14. Carlsson R, Trollfors B. Control of pertussis-lessons

learnt from a 10-year surveillance programme in Sweden. Vaccine.

2009;27:5709-18.

15. Okada K, Ohashi Y, Matsuo F, Uno S, Soh M,

Nishima S. Effectiveness of an acellular pertussis vaccine in Japanese

children during a non-epidemic period: a matched case-control study.

Epidem Infection. 2009:137:124-30.

16. World Health Organization. WHO SAGE Pertussis

Working Group. Background Paper. SAGE April 2014. Available from:

http://www.who.int/immunization/sage/ meetings/2014/april/1_Pertussis_background_FINAL4_web.pdf?

ua=. Accessed November 15, 2018.

17. World Health Organization. Use of Fractional Dose

IPV in Routine Immunization Programmes: Considerations for

Decision-making. Available from: http://www.who. int/immunization/diseases/poliomyelitis/endgame_

objective2/inactivated_polio_vaccine/fIPV_considerations_

for_decision-making_April2017.pdf?ua=1. Accessed November 6, 2018.

18. Indian Academy of Pediatrics (IAP) Advisory

committee on vaccines and Immunization Practices (ACVIP), Vasishtha VM,

Choudhary J, Yadav S, Unni JC, Jog P, Kamath SS, et al.

Introduction of inactivated poliovirus vaccine in National Immunization

Program and polio endgame strategy. Indian Pediatr.

2016;53(Suppl.1):S65-9.

19. Bahl S, Verma H, Bhatnagar P, Haldar P, Satapathy

A, Arun Kumar KN, et al. Fractional-dose inactivated poliovirus

vaccine immunization campaign — Telangana State, India, June 2016. MMWR.

2016;65:859-63.

20. Resik S, Tejeda A, Mach O, Fonseca M, Diaz M,

Alemany N, et al. Immune responses after fractional doses of

inactivated poliovirus vaccine using newly developed intradermal jet

injectors: A randomized controlled trial in Cuba. Vaccine.

2015;33:307-13.

21. Clarke E, Saidu Y, Adetifa JU, Adigweme I, Hydara

MB, Bashorun AO, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of inactivated

poliovirus vaccine when given with measles-rubella combined vaccine and

yellow fever vaccine and when given via different administration routes:

A phase 4, randomised, non-inferiority trial in The Gambia. Lancet Glob

Health. 2016;4:e534-47.

22. Troy SB, Kouiavskaia D, Siik J, Kochba E, Beydoun

H, Mirochnitchenko O, et al. Comparison of the immunogenicity of

various booster doses of inactivated polio vaccine delivered

intradermally versus intramuscularly to HIV-infected adults. J Infect

Dis. 2015;15:1969-76.

23. Saleem AF, Mach O, Yousafzai MT, Khan A, Weldon

WC, Oberste MS, et al. Needle adapters for intradermal

administration of fractional dose of inactivated poliovirus vaccine:

Evaluation of immunogenicity and programmatic feasibility in Pakistan.

Vaccine. 2017;35:3209-14.

24. Polio vaccines: WHO Position Paper, March 2016.

World Health Organization. Weekly Epidemiological Record.

2016;91:145-68.

25. World Health Organization. Detailed Review Paper

on Rotavirus Vaccines (presented to the WHO Strategic Advisory Group of

Experts (SAGE) on Immunization in April 2009). Geneva, World Health

Organization, 2009. Available from:

http://www.who.int/immunization/sage/3_Detailed_Review_Paper_on_Rota_Vaccines_17_3_2009.pdf.

Accessed November 08, 2018.

26. Phua KB, Lim FS, Lau YL, Nelson EA, Huang LM,

Quak SH, et al. Rotavirus vaccine RIX4414 efficacy sustained

during the third year of life: A randomized clinical trial in an Asian

population. Vaccine. 2012;30:4552-7.

27. Rotavirus vaccines WHO Position Paper – January

2013. Weekly Epidemiological Record. 2013;88:49-64.

28. Rotavirus. In: Hamborsky J, Kroger A,

Wolfe S, eds. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiology

and Prevention of Vaccine-preventable Diseases. 13th ed. Washington DC:

Public Health Foundation, 2015. Available from:https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/downloads/rota.pdf.

Accessed November 15, 2018.

29. World Health Organization. Rotavirus Report,

February 2012. Rotavirus Vaccines Schedules: A Systematic Review of

Safety and Efficacy from Randomized Controlled Trials and Observational

Studies of Childhood Schedules Using RV1 and RV5 Vaccines. Available

from: http://www.who.int/immunization/ sage/meetings/2012/ april/Soares_K_et_al_

SAGE_April_rotavirus.pdf. Accessed November 08, 2018.

30. World Health Organization. Grading of Scientific

Evidence – Tables 1–4: Does RV1and RV5 induce protection against

rotavirus morbidity and mortality in young children both in low and high

mortality settings? Available from:

http://www.who.int/immunization/position_papers/rotavirus_

grad_rv1_rv5_protection. Accessed November 8, 2018.

31. Naik SP, Zade JK, Sabale RN, Pisal SS, Menon R,

Bankar SG, et al. Stability of heat stable, live attenuated

rotavirus vaccine (ROTASIIL®). Vaccine. 2017;35:2962-9.

32. World Health Organization. Background Paper on

Typhoid Vaccines for SAGE Meeting (October 2017). Available from:

http://www.who.int/immunization/sage /meetings/ 2017/october/1_Typhoid_SAGE_background_paper_

Final_v3B.pdf. Accessed November 08, 2018.

33. World Health Organization. Guidelines on The

Quality, Safety and Efficacy of Typhoid Conjugate Vaccines, 2013.

Available from:

http://www.who.int/biologicals/areas/vaccines/TYPHOID_BS2215_doc_v1.14_WEB_

VERSION. pdf. Accessed July 12, 2016.

34. Britto C, Pollard AJ, Voysey M, Blohmke CJ. An

appraisal of the clinical features of pediatric enteric fever:

Systematic review and meta-analysis of the age-stratified disease

occurrence. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64:1604-11.

35. World Health Organization. Background Paper to

SAGE on Typhoid Policy Recommendations. 2017. Available from:

http://www.who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2017/october/1_Typhoid_SAGE_background_paper_Final_v3B.

pdf?ua=1. Accessed November 08, 2018.

36. Typhoid vaccines: WHO Position Paper – March

2018. Weekly Epidemiological Record. 2018;93:153-72.

37. Voysey M, Pollard AJ. Sero-efficacy of

Vi-polysaccharide tetanus-toxoid typhoid conjugate vaccine (Typbar-TCV).

Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67:18-24.

38. Vashishtha VM, Yewale VN, Bansal CP, Mehta PJ.

Indian Academy of Pediatrics, Advisory Committee on Vaccines and

Immunization Practices (ACVIP). IAP perspectives on measles and rubella

elimination strategies. Indian Pediatr. 2014;51:719-22.

39. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Measles, Mumps, and Rubella (MMR) Vaccination: What Everyone Should

Know. Available from:

https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/mmr/public/index.html. Accessed

November 18, 2018.

40. Nair H, Brooks WA, Katz M, Roca A, Berkley JA,

Madhi SA, et al. Global burden of respiratory infections due to

seasonal influenza in young children: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Lancet. 2011;378:1917-30.

41. Rudan I, Theodoratou E, Zgaga L, Nair H, Chan KY,

Tomlinson M, et al. Setting priorities for development of

emerging interventions against childhood pneumonia, meningitis and

influenza. J Glob Health. 2012;2:10304.

42. Venkatesh M, Doarn CR, Steinhoff M, Yung J.

Assessment of burden of seasonal influenza in India and consideration of

vaccination policy. Glob J Med Pub Health. 2016;5:1-10. Available from:

http://www.gjmedph.com/uploads/R1-Vo5No5.pdf. Accessed November

18, 2018.

43. Vashishtha VM, Kalra A, Choudhury P. Influenza

vaccination in India: Position Paper of Indian Academy of Pediatrics,

2013. Indian Pediatr. 2013;50:867-74.

44. Hirve S, Krishnan A, Dawood FS, Lele P, Saha S,

Rai S, et al. Incidence of influenza-associated hospitalization

in rural communities in western and northern India, 2010-2012: A

multi-site population-based study. J Infect. 2015;70: 160-70.

45. Chadha MS, Broor S, Gunasekaran P, Potdar VA,

Krishnan A, Chawla-Sarkar M, et al. Multisite virological

influenza surveillance in India: 2004-2008. Influenza Other Respir

Viruses. 2012;6:196-203.

46. Caini S, Huang QS, Ciblak MA, Kusznierz G, Owen

R, Wangchuk S, et al. Epidemiological and virological

characteristics of influenza B: results of the Global Influenza B Study.

Influen Other Respir Viruses. 2015;9:3-12.

47. Grohskopf LA, Sokolow LZ, Broder KR, Walter EB,

Fry AM, Jernigan DB. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with

vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization

Practices – United States, 2018-19 Influenza Season. MMWR Recomm Rep.

2018;67:1-20.

48. World Health Organization. Rabies vaccines: WHO

Position Paper, April 2018 Recommendations. Vaccine. 2018;36:5500-3.

49. Gogtay NJ, Munshi R, Ashwath Narayana DH,

Mahendra BJ, Kshirsagar V, Gunale B, et al. Comparison of a novel

human rabies monoclonal antibody to human rabies immunoglobulin for

postexposure prophylaxis: A phase 2/3, randomized, single-blind,

noninferiority, controlled study. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66:387-95.

|

|

|

|

|